Pianola Journal 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Page 1 (1/31/20) Waltz in E-Flat Major, Op. 19 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

Page 1 (1/31/20) Waltz in E-flat major, Op. 19 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN (1810-1849) Composed in 1831. Chopin’s Waltz in E-flat major, Op. 18, his first published specimen of the genre and one of his most beloved, was composed in 1831, when he was living anxiously in Vienna, almost unknown as a composer and only slightly appreciated as a pianist. In 1834, he sold it to the Parisian publisher Pleyel to finance his trip with Ferdinand Hiller to the Lower Rhineland Music Festival at Aachen, where Hiller introduced him to his long-time friend Felix Mendelssohn. The piece was dedicated upon its publication to Mlle. Laura Horsford, one of two sisters Chopin then counted among his aristocratic pupils. (Sister Emma had received the dedication of the Variations on “Je vends des scapulaires” from Hérold’s Ludovic, Op. 12 the year before.) The Waltz in E-flat follows the characteristic Viennese form of a continuous series of sixteen- measure strains filled with both new and repeated melodies that are capped by a vigorous coda. Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Composed 1831. In the Ballades, “Chopin reaches his full stature as the unapproachable genius of the pianoforte,” according to Arthur Hedley, “a master of rich and subtle harmony and, above all, a poet — one of those whose vision transcends the confines of nation and epoch, and whose mission it is to share with the world some of the beauty that is revealed to them alone.” Though the Ballades came to form a nicely cohesive set unified by their temporal scale, structural fluidity and supranational idiom, Chopin composed them over a period of more than a decade. -

Die Ukraine Zwischen Ost Und West

Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald Greifswalder Ukrainistische Hefte Heft 4 Die Ukraine zwischen Ost und West Rolf Göbner zum 65. Geburtstag Herausgegeben von Ulrike Jekutsch und Alexander Kratochvil Shaker Verlag Aachen 2007 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Gedruckt mit finanzieller Unterstützung der Philosophischen Fakultät der E.-M.-Arndt-Universität Greifswald und der Deutschen Assoziation der Ukrainisten Greifswalder Ukrainistische Hefte Herausgeber: Alexander Kratochvil Redaktionsrat: Guido Hausmann, Timofij Havryliv, Michael Moser Copyright Shaker Verlag 2007 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes, der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe, der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungs- anlagen und der Übersetzung, vorbehalten. Printed in Germany. ISBN 978-3-8322-6625-7 ISSN 1860-2215 Shaker Verlag GmbH • Postfach 101818 • 52018 Aachen Telefon: 02407 / 95 96 - 0 • Telefax: 02407 / 95 96 - 9 Internet: www.shaker.de • E-Mail: [email protected] 3 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Geleitwort der Herausgeber 9 Anatolij Tkaenko Ukrainicum – – (-) 12 LITERATURWISSENSCHAFT Mychajlo Najenko . 15 Mykola Sulyma „“ 26 Anna-Halja Horbatsch Tschornobyl in der ukrainischen Literatur 33 Stefanija Andrusiv 0* 0 40 Jutta Lindekugel Pseudonyme schreibender Frauen in der ukrainischen Literatur Ende 19. - Anfang 20. Jahrhundert: -

Fernando Laires

Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 An officiIn AMemoriam:l publicAtion of the AmericFernandoAn liszt society, Laires inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 1 In Memoriam: Fernando Laires In Memoriam: Fernando Laires TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 2 President's Message In Memoriam: Fernando Laires TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 31 LetterIn Memoriam: from the FernandoEditor Laires 1 42In Memoriam:"APresident's Tribute toMessage Fernando Fernando Laires Laires," by Nancy Lee Harper 2 3President's Letter from Message the Editor 5 More Tributes to Fernando Laires 3 4Letter "A fromTribute the to Editor Fernando Laires," 7 Membershipby Nancy Lee Updates, Harper Etc. 4 "A Tribute to Fernando Laires," 85by NancyInvitationMore TributesLee to Harper the to 2017 Fernando ALS FestivalLaires in Evanston/Chicago 5 7More Membership Tributes to Updates, Fernando Etc. Laires 10 "Los Angeles International Liszt Competition Overview" 7 8Membership byInvitation Éva Polgár Updates, to the 2017 Etc. ALS Festival in Evanston/Chicago 8 InvitationIn Memoriam to the 2017 ALS Festival in Evanston/Chicago 10 JALS"Los AngelesUpdate International Liszt Competition Overview" 10 "Losby Angeles Éva Polgár International Liszt 11 Competition Chapter News Overview" In Memoriam by Éva Polgár 12 Member News In MemoriamJALS Update 1511JALS FacsimileChapter Update News Frontispiece of Liszt's "Dante" Symphony Fernando Laires with his wife and fellow pianist, Nelita True, in 2005. Photo: Rochester NY Democrat & Chronicle Staff Photographer Carlos Ortiz: http://www. 11 12Chapter Member News News democratandchronicle.com/story/lifestyle/music/2016/10/02/fernando-laires-eastman-liszt- 16 Picture Page obituary/91266512, accessed on November 12, 2016. -

Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor

Minnesota Musicians ofthe Cultured Generation Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor The appeal ofAmerica 1) Early life & arrival in Minneapolis 2) Work in Minneapolis 3) Into the out-of-doors 4) Death & appraisal Robert Tallant Laudon Professor Emeritus ofMusicology University ofMinnesota 924 - 18th Ave. SE Minneapolis, Minnesota 55414 (612) 331-2710 [email protected] 2002 Heinrich Hoevel (Courtesy The Minnesota Historical Society) Heinrich Hoevel Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor A veritable barrage ofinformation made the New World seem like an answer to all the yearnings ofpeople ofthe various German States and Principalities particularly after the revolution of 1848 failed and the populace seemed condemned to a life of servitude under the nobility and the military. Many of the Forty-Eighters-Achtundvierziger-hoped for a better life in the New World and began a monumental migration. The extraordinary influx of German immigrants into America included a goodly number ofgifted artists, musicians and thinkers who enriched our lives.! Heinrich Heine, the poet and liberal thinker sounded the call in 1851. Dieses ist Amerika! This, this is America! Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Nicht die heutige, die schon Not the present-day already Europaisieret abwelkt. -- Faded Europeanized one. Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Wie sie Christoval Kolumbus Such as Christopher Columbus Aus dem Ozean hervorzog. Drew from out the depths of -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

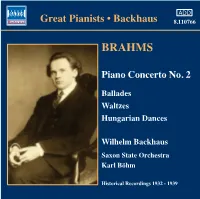

110766 Bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23Am Page 4

110766 bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23am Page 4 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Waltzes, Op. 39 ADD Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83 7 No. 1 in B major 0:50 Great Pianists • Backhaus 8.110766 8 No. 2 in E major 1:12 1 Allegro non troppo 16:04 9 No. 3 in G sharp minor 0:43 2 Allegro appassionato 8:05 0 No. 4 in E minor 0:30 3 Andante 11:53 ! No. 5 in E major 1:01 4 Allegretto grazioso 9:06 @ No. 6 in C sharp major 0:53 # No. 7 in C sharp minor 1:10 Saxon State Orchestra • Karl Böhm $ No. 8 in B flat major 0:35 BRAHMS % No. 9 in D minor 0:50 Recorded June, 1939 in Dresden ^ No. 10 in G major 0:29 Matrices: 2RA 3956-2, 3957-1, 3958-1, 3959-3A, & No. 11 in B minor 0:39 3960-1, 3961-1A, 3962-1, 3963-3, 3964-3A, * No. 12 in E major 0:49 3965-2, 3966-2 and 3967-1 ( No. 13 in B major 0:26 First issued on HMV DB 3930 through 3935 ) No. 14 in G sharp minor 0:36 Piano Concerto No. 2 ¡ No. 15 in A flat major 1:18 Ballades, Op. 10 ™ No. 16 in C sharp minor 1:10 5 No. 1 in D minor (“Edward”) 4:07 Recorded 27th January, 1936 6 No. 2 in D major 4:59 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 Ballades Matrices: 2EA 3010-5, 3011-5 and 3012-4 Recorded 5th December, 1932 First issued on HMV DB 2803 and 2804 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. -

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON at PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON AT PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018 Peabody Conductors' Orchestra Tuesday, November 27, 2018 Peabody Symphony Orchestra Saturday, December 1, 2018 STEINWAY. YAMAHA. [ YOUR NAME HERE ] With your gi to the Piano Excellence Fund at Peabody, you can add your name to the quality instruments our outstanding faculty and students use for practice and performance every day. The Piano Department at Peabody has a long tradition of excellence dating back to the days of Arthur Friedheim, a student of Franz Liszt, and continuing to this day, with a faculty of world-renowned artists including the eminent Leon Fleisher, who can trace his pedagogical lineage back to Beethoven. Peabody piano students have won major prizes in such international competitions as the Busoni, Van Cliburn, Naumburg, Queen Elisabeth, and Tchaikovsky, and enjoy global careers as performers and teachers. The Piano Excellence Fund was created to support this legacy of excellence by funding the needed replacement of more than 65 pianos and the ongoing maintenance and upkeep of nearly 200 pianos on stages and in classrooms and practice rooms across campus. To learn more about naming a piano and other creative ways to support the Peabody Institute, contact: Jessica Preiss Lunken, Associate Dean for External Affairs [email protected] • 667-208-6550 Welcome back to Peabody and the Miriam A. Friedberg Concert Hall. This month’s programs show o a remarkable array of musical styles and genres especially as related to Peabody’s newly imagined ensembles curriculum, which has evolved as part of creating the Conservatory’s groundbreaking Breakthrough Curriculum. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) S Elise Braun Barnett

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) s Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections Elise Braun Barnett Introduction Otto Deri often used to discuss programs for piano recitals with me. More than once he expressed surprise that the late piano compositions of Liszt were performed only rarely. He recommended their serious study since, as he pointed out, in these pieces Liszt's conception of melody, rhythm, and harmony are quite novel and anticipate Debussy, Ravel, and Bartok. These discussions came to mind when a friend of mine, Mrs. Oscar Kanner, a relative of Moriz Rosenthal,! showed me an article by the pianist entitled "Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections," which had appeared in a 1911 issue of the journal Die Musik,2 and also a handwritten, unpublished autobiography written in New York during the last years of Rosenthal's life, 1940 to 1946. Rosenthal's concerts in Europe and America are still remembered by the older generation. His musical conceptions, emotions projected on the piano with an amazing technique, remain an unforgettable experience. He is also remembered as having been highly cultivated, witty, and sometimes sar- castic. His skill in writing is less known, but his autobiography and essays reveal a most refined, fluent, and vivid German style. He is able to conjure up the "golden days," when unity of form and content was appreciated. It is my hope that the following annotated translation of Rosenthal's article will provide a worthy tribute to the memory of Otto Deri. Translation In October of 1876, as a youngster of thirteen, I played for Franz Liszt during one of his frequent visits to the Schottenhof in Vienna,3 and I was admitted to his much envied entourage as perhaps the youngest of his disciples. -

U.S. Sheet Music Collection

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP I, SERIES 3, SUB-SERIES A (INSTRUMENTAL) Consists of instrumental sheet music published between 1826 and 1860. Titles are arranged in alphabetical order by surname of known composer or arranger; anonymous compositions are inserted in alphabetical order by title. ______________________________________________________________________________ Box 12 Abbot, John M. La Coralie polka schottisch. Composed for and respectfully dedicated to Miss Kate E. Stoutenburg. For solo piano. New York: J. E. Gould and Co., 1851. Abbot, John M. La reve d’amour. For solo piano. New York: William Hall & Son, 1858. 3 copies. L’Aboyar. La coquetterie polka facile. For solo piano. Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1853. Adam, Adolphe. Duke of Reichstadt’s waltz. For solo piano. New York: James L. Hewitt & Co., [s.d.]. Adam, Adolphe. Duke of Reichstadt’s waltz. For solo piano. Boston: C. Bradlee, [s.d.].. Adam, A. Hungarian flag dance. Danced by forty-eight Danseuses Viennoises at the principal theatres in Europe and the United States. For solo piano. Arranged by Edward L. White. Boston: Stephen W. Marsh, 1847. Adams, A.M. La petite surprise! For solo piano. New York: W. Dubois, [s.d.]. Adams, G. Molly put the kettle on. For solo piano. Boston: Oliver Ditson, [s.d.]. Adams, G. Scotch air. With variations as performed by Miss. R. Brown on the harp at the Boston Concerts. For solo piano or harp. New York: William Hall & Son, [s.d.]. Adams, G. Scotch air. With variations as performed by Miss R. Brown on the harp at the Boston Concerts. For solo piano or harp.