USHMM Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

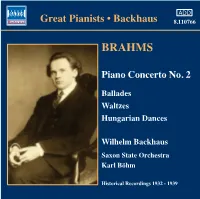

110766 Bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23Am Page 4

110766 bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23am Page 4 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Waltzes, Op. 39 ADD Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83 7 No. 1 in B major 0:50 Great Pianists • Backhaus 8.110766 8 No. 2 in E major 1:12 1 Allegro non troppo 16:04 9 No. 3 in G sharp minor 0:43 2 Allegro appassionato 8:05 0 No. 4 in E minor 0:30 3 Andante 11:53 ! No. 5 in E major 1:01 4 Allegretto grazioso 9:06 @ No. 6 in C sharp major 0:53 # No. 7 in C sharp minor 1:10 Saxon State Orchestra • Karl Böhm $ No. 8 in B flat major 0:35 BRAHMS % No. 9 in D minor 0:50 Recorded June, 1939 in Dresden ^ No. 10 in G major 0:29 Matrices: 2RA 3956-2, 3957-1, 3958-1, 3959-3A, & No. 11 in B minor 0:39 3960-1, 3961-1A, 3962-1, 3963-3, 3964-3A, * No. 12 in E major 0:49 3965-2, 3966-2 and 3967-1 ( No. 13 in B major 0:26 First issued on HMV DB 3930 through 3935 ) No. 14 in G sharp minor 0:36 Piano Concerto No. 2 ¡ No. 15 in A flat major 1:18 Ballades, Op. 10 ™ No. 16 in C sharp minor 1:10 5 No. 1 in D minor (“Edward”) 4:07 Recorded 27th January, 1936 6 No. 2 in D major 4:59 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 Ballades Matrices: 2EA 3010-5, 3011-5 and 3012-4 Recorded 5th December, 1932 First issued on HMV DB 2803 and 2804 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Fourteenth United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal

Fourteenth 29 January 2021 United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and English only Criminal Justice Kyoto, Japan, 7–12 March 2021 Item 5 of the provisional agenda* Multidimensional approaches by Governments to promoting the rule of law by, inter alia, providing access to justice for all; building effective, accountable, impartial and inclusive institutions; and considering social, educational and other relevant measures, including fostering a culture of lawfulness while respecting cultural identities, in line with the Doha Declaration ** Background documents received from individual experts Białystok Legal Studies Prepared by Sławomir Redo __________________ * A/CONF.234/1/Rev.1. ** The designations employed, the presentation of material and the views expressed in the paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat and do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. V.21-00585 (E) *2100585* UNIWERSYTET W BIAŁYMSTOKU WYDZIAŁ PRAWA BIAŁOSTOCKIE STUDIA PRAWNICZE BIAŁYSTOK 2018 VOLUME 23 nr 3 Advancing Culture of Lawfulness: Towards the Achievement of the 2030 Agenda BIAŁOSTOCKIE STUDIA PRAWNICZE VOLUME 23 nr 3 Editor-in-Chief of the Publisher Wydawnictwo Temida 2: Cezary Kosikowski Chair of the Advisory Board of the Publisher Wydawnictwo Temida 2: Emil W. Pływaczewski Advisory Board: Representatives of the University of Białystok: Stanisław Bożyk, Leonard Etel, Ewa M. Guzik-Makaruk, Adam Jamróz, Dariusz Kijowski, Cezary Kosikowski, Cezary Kulesza, Agnieszka Malarewicz-Jakubów, Maciej Perkowski, Stanisław Prutis, Eugeniusz Ruśkowski, Walerian Sanetra, Joanna Sieńczyło- Chlabicz, Ryszard Skarzyński, Halina Święczkowska, Jaroslav Volkonovski, Mieczysława Zdanowicz. -

EILEEN JOYCE the Complete Parlophone & Columbia Solo Recordings 1933–1945

EILEEN JOYCE The complete Parlophone & Columbia solo recordings 1933–1945 THE MATTHAY PUPILS 2 EILEEN JOYCE The complete Parlophone & Columbia solo recordings 1933–1945 3 1 The Parlophone 78s (78.28) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750) 1. Fantasia and Fugue in A minor BWV944 E11354 (matrices CXE 8936/7), recorded on 7 February 1938 (5.27) NB: This title has been misattributed as BWV894 in all previous reissues DOMENICO PARADIES (1707–1791) 2. Toccata in A major from Sonata No 6 E11354 (matrix CXE 8937), recorded on 7 February 1938 (2.36) WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) 3. Rondo in A major K386 (orchestra/Clarence Raybould) E11292 (matrices CXE 7450/1), (7.29) recorded on 2 February 1936 Suite K399 excerpts 4. Allemande E11443 (matrix CXE 9813), recorded on 26 May 1939 (1.54) 5. Courante (2.18) Sonata in C major K545 (13.03) 6. Allegro E11442/3 (matrices CXE 10382/4), recorded on 26 May 1940 (4.34) 7. Andante (6.46) 8. Rondo (1.43) FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) 9. Andante in A major D604 E11403 (matrix CXE9619), recorded on 7 February 1939 (4.58) 10. Impromptu in E flat major D899 No 2 E11403 (matrix CXE9620), recorded on 7 February 1939 (4.09) 11. Impromptu in A flat major D899 No 4 E11440 (matrices CXE 10217/8), recorded on 18 December 1939 (7.34) FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN (1810–1849) 12. Nocturne in E flat major Op 9 No 2 E11448 (matrix CXE 10467), recorded on 3 May 1940 (4.42) 13. Nocturne in B major Op 32 No 1 E11448 (matrix CXE 10466), recorded on 3 May 1940 (4.30) 14. -

Beth Levin Inward Voice

1838 — 1973 — 1828 Beth Levin Inward Voice Robert Schumann: Kreisleriana Anders Eliasson: Versione Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata in C minor D 958 LC 28016 Beth Levin / Inward Voice Studio Live Recording Robert Schumann (1810 — 56) Kreisleriana. Fantasien op. 16. Seinem Freunde Frédéric Chopin zugeeignet (1838) 1 32’ 38“ I Äußerst bewegt. II Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch * Intermezzo I. Sehr lebhaft - Erstes Tempo - Intermezzo II. Etwas bewegter - Langsamer (erstes Tempo) III Sehr aufgeregt * Etwas langsamer – Erstes Tempo – Noch schneller IV Sehr langsam * Bewegter – Erstes Tempo V Sehr lebhaft VI Sehr langsam * Etwas bewegter – Erstes Tempo VII Sehr rasch * Noch schneller – Etwas langsamer VIII Schnell und spielend Anders Eliasson (1947 — 2013) Versione per pianoforte (1973) 2 06’ 54“ Franz Peter Schubert (1797 — 1828) Sonate c-moll D 958 (1828) I Allegro 3 08’ 52“ II Adagio 4 12’ 37“ III Menuett. Allegro 5 03’ 10“ IV Allegro 6 10’ 17“ total 73’ 30“ Beth Levin In Beth Levins Spiel sind die Einflüsse Beth Levin fashions a uniquely transcen- mächtiger pianistischer und musikalisch- dent and personal style that combines four tow- kultureller Traditionen zu einem unver- ering pianistic, musical and cultural traditions. kennbar eigentümlichen Stil transzendiert: From her first great teacher, Marian Filar, Le- die polnische Schule kantabler klanglicher vin acquired the melodic and timbral refinement Verfeinerung ihres ersten großen Lehrers of the Polish school. Another early influence, Ru- Marian Filar; die strukturelle Klarheit und dolf Serkin, fostered a sense of structural clarity musikantische Natürlichkeit Rudolf Ser- and natural musicianship, while Leonard Shure kins; die monumentale Kraft und unwider- demonstrated his monumental force and irresis- stehliche Brillanz Leonard Shures; und die tible brilliance to his young student. -

12, 2000 Gusman Center for the Performing Arts, 174 East Flagler Street, Miami

March 4 - 12, 2000 Gusman Center for the Performing Arts, 174 East Flagler Street, Miami First Prize Second Prize Third Prize Co-Winner Ning An Jun Asai Brenda Huang Third Prize Co-Winner Fifth Prize Sixth Prize Hiroko Kunitake Katherine Lee James Lent 6 Lady Blanka A. Rosenstiel Jadwiga Gewert Executive Director, Chopin Foundation of the United States, Inc. Maestro Tadeusz Strugala Grant Johannesen Agustin Anievas Ivan Davis Ian Hobson Constance Keene Chairman Janusz Olejniczak Gersende de Sabran Ruth Slenczynska Susan Starr Alan Gampel Marian Filar Juliette de Marcellus Ning An Jun Asai Andrew Brownell Keith Chambers Dawn Chan Stephanie Chou Melody Fader Inna Faliks Andre von Frasunkiewicz Laura Garritson Brenda Huang U-Jung Jung Lynn Kao Angela Kim Keith Kirchoff Hiroko Kunitake Katherine Lee James Lent Emi Nakajima Quynh Nguyen Evgenia Pilyavina Christopher Weldon Regina Yah Kay Zavislak First Prize $15,000 Awarded by Harriet Irsay and Concert debut at Carnegie Hall/Weill Recital Hall sponsored by the Chopin Foundation New York Council and A twenty-engagement United States concert tour arranged by the Chopin Foundation of the United States Second Prize $10,000 Awarded by Donald Carlin Third Prize $5,000 Awarded by Jean Black Fourth Prize $4,000 Awarded by Olga and David Melin The top four prize winners will also travel to Warsaw, Poland to compete in the International Chopin Piano Competition, with all expenses underwritten by a grant from the Frank Stanley Beveridge Foundation Fifth Prize $3,000 Awarded by the Chopin Foundation South Florida Council Sixth Prize $2,000 Awarded by Dr. F. Warren O’Reilly Special Prizes $1,000 for Best Performance of a Mazurka Awarded in memory of Andrzej Wasowski $1,000 for Best Performance of a Polonaise Awarded in memory of Dr. -

BSP 21Eng.Indb

UNIVERSITY OF BIAŁYSTOK FACULTY OF LAW BIAŁOSTOCKIE STUDIA PRAWNICZE BIAŁYSTOK 2016 VOLUME 21 Ministry of Science and Higher Education Republic of Poland Creation of the English-language versions of the articles published in the „Białostockie Studia Prawnicze” [Białystok Legal Studies] funded under the contract no. 548/P-DUN/2016 and 548/1/P-DUN/2016 from resources of the Minister of Science and Higher Education dedicated to the popularisation of science. Stworzenie anglojęzycznych wersji wydawanych publikacji w “Białostockich Studiach Prawniczych” fi nansowane w ramach umowy 548/P-DUN/2016 i 548/1/P-DUN/2016 ze środków Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego przeznaczonych na działalność upowszechniającą naukę. BIAŁOSTOCKIE STUDIA PRAWNICZE VOLUME 21 Editor-in-Chief of the Publisher Wydawnictwo Temida 2: Cezary Kosikowski Chair of the Advisory Board of the Publisher Wydawnictwo Temida 2: Emil W. Pływaczewski Advisory Board: Representatives of the University of Białystok: Stanisław Bożyk, Leonard Etel, Ewa M. Guzik-Makaruk, Adam Jamróz, Dariusz Kijowski, Cezary Kosikowski, Cezary Kulesza, Agnieszka Malarewicz-Jakubów, Maciej Perkowski, Stanisław Prutis, Eugeniusz Ruśkowski, Walerian Sanetra, Joanna Sieńczyło-Chlabicz, Ryszard Skarzyński, Halina Święczkowska, Jaroslav Volkonovski, Mieczysława Zdanowicz. Representatives of other Polish Universities: Marian Filar (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Edward Gniewek (University of Wrocław), Lech Paprzycki (Kozminski University in Warsaw), Stanisław Waltoś (Jagiellonian University in Kraków). Representatives of Foreign Universities and Institutions: Lilia Abramczyk (Janek Kupała State University in Grodno, Belarus),Vladimir Babčak (University of Kosice, Slovakia), Renata Almeida da Costa (University of La Salle, Brazil), Chris Eskridge (University of Nebraska, the USA), Jose Luis Iriarte (University of Nebraska, the USA) Marina Karasjewa (University of Voronezh, Russia), Alexei S. -

Kalgoorlie-Boulder Walk of Fame Eileen Joyce 1908-1991

KALGOORLIE-BOULDER WALK OF FAME EILEEN JOYCE 1908-1991 Eileen Joyce, a miner’s daughter from Boulder became one of the century’s most famous pianists. Her debut at a Proms Concert in London paved the way to a glittering international career which saw her feature on the soundtrack of a number of major films and the publication of a children’s book based on her early life. Picture EG-N-122-033 courtesy of the © Eastern Goldfields Historical Society. Joyce, Eileen Alannah (1908–1991) by Ava Hubble The Australian pianist Eileen Joyce, who died in England on March 25, rose from poverty- stricken obscurity to become one of this century's most famous concert stars. She was one of the four children of Irish immigrants, Joseph and Alice Joyce, and she was born in a tent at Zeehan, Tasmania, in 1912 [1908]. She spent most of her childhood in Boulder, Western Australia, where her father worked as a miner. The family lived opposite a miners' saloon run by a relative and it was there that Eileen first began experimenting at the keyboard, tinkering on a battered old piano in the bar. Her love of music was encouraged by nuns at the local convent school and when she was about 10 they recommended that she be sent to develop her talents at a larger convent in Perth. She was never to forget her father's embarrassment when he was forced to admit that he could neither read nor write when enrolling her at the city school. When Percy Grainger was invited to the convent to hear her play, he pronounced her "the most transcendentally gifted child" he had ever met. -

Bösendorfer - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 1/5/14, 3:08 PM Bösendorfer from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Bösendorfer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1/5/14, 3:08 PM Bösendorfer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bösendorfer (L. Bösendorfer Klavierfabrik GmbH) is an L. Bösendorfer Klavierfabrik GmbH Austrian piano manufacturer, and a wholly owned subsidiary of Yamaha.[citation needed] Bösendorfer is unusual in that it produces 97- and 92-key models in addition to instruments with standard 88-key keyboards. Type private Contents Industry Musical instruments Founded 1828 1 Characteristics Founder(s) Ignaz Bösendorfer 2 History Headquarters Vienna, Austria 3 Models 3.1 Standard Black Models[7] Products Pianos 3.2 Conservatory Series Parent Yamaha Corporation 3.3 Special and Limited editions 3.3.1 SE reproducing piano Website www.boesendorfer.com 3.4 Designer Models (http://www.boesendorfer.com/) 4 Noteworthy events 5 Bösendorfer Artists 5.1 Recordings 5.1.1 Classical 5.1.2 Popular 6 References 7 Bibliography 8 External links Characteristics Bösendorfer pioneered the extension of the typical 88-key keyboard, creating the Imperial Grand (Model 290), which has 97 keys (eight octaves). This innovation was originally ordered as a custom built piano for Ferruccio Busoni, who wanted to transcribe an organ piece that went to the C below the standard keyboard. This innovation worked so well, that this piano was added to regular product offerings and quickly became one of the world's most sought-after concert grands. Because of the 290's success, the extra strings were added to Bösendorfer's other line of instruments such as the 225 model, which -

CHRZEŚCIJAŃSKIE DZIEDZICTWO DUCHOWE NARODÓW SŁOWIAŃSKICH Wydawca: Temida 2 Przy Współpracy I Wsparciu Finansowym Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu W Białymstoku

CHRZEŚCIJAŃSKIE DZIEDZICTWO DUCHOWE NARODÓW SŁOWIAŃSKICH Wydawca: Temida 2 Przy współpracy i wsparciu finansowym Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku Redaktor Naukowy Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Cezary Kosikowski Rada Naukowa Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Przewodniczący Rady Naukowej Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Emil W. Pływaczewski Członkowie z Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku: Stanisław Bożyk, Leonard Etel, Ewa M. Guzik ‑Makaruk, Adam Jamróz, Dariusz Kijowski, Cezary Kosikowski, Cezary Kulesza, Jarosław Ławski, Agnieszka Malarewicz ‑Jakubów, Maciej Perkowski, Stanisław Prutis, Eugeniusz Ruśkowski, Walerian Sanetra, Joanna Sieńczyło ‑Chlabicz, Ryszard Skarzyński, Halina Święczkowska, Jaroslav Volkonovski, Mieczysława Zdanowicz Członkowie z Polski: Marian Filar (Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu), Edward Gniewek (Uniwersytet Wrocławski), Lech Paprzycki (Sąd Najwyższy) Członkowie zagraniczni: Lidia Abramczyk (Państwowy Uniwersytet im. Janki Kupały w Grodnie, Białoruś), Vladimir Babčak (Uniwersytet w Koszycach, Słowacja), Renata Almeida da Costa (Uniwersytet La Salle, Brazylia), Chris Eskridge (Uniwersytet w Nebrasce, USA), José Luis Iriarte Ángel (Uniwersytet Navarra, Hiszpania), Marina Karasjewa (Uniwersytet w Woroneżu, Rosja), Bernhard Kitous (Uniwersytet w Rennes, Francja), Martin Krygier (Uniwersytet w Nowej Południowej Walii, Australia), Petr Mrkyvka (Uniwersytet Masaryka, Czechy), Marcel Alexander Niggli (Uniwersytet we Fryburgu, Szwajcaria), Andrej A. Novikov (Państwowy Uniwersytet w Sankt Petersburgu, Rosja), Sławomir Redo (Uniwersytet