EILEEN JOYCE the Complete Parlophone & Columbia Solo Recordings 1933–1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto in the Film Brief

Soundtrack to a Love Story: The Use of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto In the Film Brief Encounter Sean O’Connor MHL 252 April 22, 2013 Soundtrack to a Love Story 1 Classic FM, an independent radio station in the United Kingdom, has held a poll each Easter weekend since 1996 where listeners can vote on the top 300 most popular works of classical music. In 2013, Sergei Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor filled the number-one spot for the third year in a row. However, when BBC News first published an online article about this in April 2011, the headline did not mention the composition’s actual title. Instead, it referred to the concerto as the “Brief Encounter theme”1. Rather than being known as a concerto by Rachmaninov, many listeners in the United Kingdom recognize the music as the score prominently used in the classic British motion picture Brief Encounter (1945). How is it that so many listeners associate the music with this film rather than as arguably Rachmaninov’s most celebrated work? To determine the reason, listeners must critically analyze the concerto and the film together to find a unifying emotion through recurring themes. This analysis will do just that, examining each movement and where excerpts from those movements appear in the film. That analysis must begin, however, with background information on both works. Today, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto is considered one of the finest musical compositions of the late romantic period, as well as, according to the poll mentioned earlier, one of the most popular pieces of “classical music” around the world. -

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

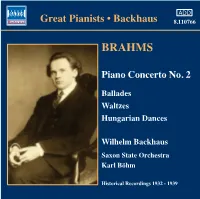

110766 Bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23Am Page 4

110766 bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23am Page 4 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Waltzes, Op. 39 ADD Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83 7 No. 1 in B major 0:50 Great Pianists • Backhaus 8.110766 8 No. 2 in E major 1:12 1 Allegro non troppo 16:04 9 No. 3 in G sharp minor 0:43 2 Allegro appassionato 8:05 0 No. 4 in E minor 0:30 3 Andante 11:53 ! No. 5 in E major 1:01 4 Allegretto grazioso 9:06 @ No. 6 in C sharp major 0:53 # No. 7 in C sharp minor 1:10 Saxon State Orchestra • Karl Böhm $ No. 8 in B flat major 0:35 BRAHMS % No. 9 in D minor 0:50 Recorded June, 1939 in Dresden ^ No. 10 in G major 0:29 Matrices: 2RA 3956-2, 3957-1, 3958-1, 3959-3A, & No. 11 in B minor 0:39 3960-1, 3961-1A, 3962-1, 3963-3, 3964-3A, * No. 12 in E major 0:49 3965-2, 3966-2 and 3967-1 ( No. 13 in B major 0:26 First issued on HMV DB 3930 through 3935 ) No. 14 in G sharp minor 0:36 Piano Concerto No. 2 ¡ No. 15 in A flat major 1:18 Ballades, Op. 10 ™ No. 16 in C sharp minor 1:10 5 No. 1 in D minor (“Edward”) 4:07 Recorded 27th January, 1936 6 No. 2 in D major 4:59 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 Ballades Matrices: 2EA 3010-5, 3011-5 and 3012-4 Recorded 5th December, 1932 First issued on HMV DB 2803 and 2804 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. -

Western Australia), 1900-1950

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2007 An investigation of musical life and music societies in Perth (Western Australia), 1900-1950 Jessica Sardi Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Other Music Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Sardi, J. (2007). An investigation of musical life and music societies in Perth (Western Australia), 1900-1950. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1290 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1290 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. Youe ar reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

GEOFFREY TOZER in CONCERT Osaka 1994

GEOFFREY TOZER IN CONCERT Osaka 1994 Mozart Concerto K 467 • Liszt Raussian Folk Song + Rigoletto + Nighingale Geoffrey Tozer in Concert | Osaka 1994 Osaka Symphony Orchestra Wolfgang Amedeus Mozart (1756-1791) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra no. 21 in C, K 467 1 Allegro 13’34” 2 Romance 6’40” 3 Rondo. Allegro assai 7’14” Franz Liszt (1811-1886) 4 Russian Folk Song 2’55” 5 Rigoletto 6’44” 6 Nightingale 4’04” Go to move.com.au for program notes for this CD, and more information about Geoffrey Tozer There are more concert recordings by Geoffrey Tozer … for details see: move.com.au P 2014 Move Records eoffrey Tozer was an artist of Churchill Fellowship (twice, Australia), MBS radio archives in Melbourne and the first rank, a consummate the Australian Creative Artists Fellowship Sydney, the BBC archives in London and musician, a concert pianist (twice, Australia), the Rubinstein Medal in archives in Israel, China, Hungary, and recitalist with few peers, (twice, Israel), the Alex de Vries Prize Germany, Finland, Italy, Russia, Mexico, Gpossessing perfect pitch, a boundless (Belgium), the Royal Overseas League New Zealand, Japan and the United musical memory, the ability to improvise, (United Kingdom), the Diapason d’Or States, form an important part of Tozer’s to transpose instantly into any key or (France), the Liszt Centenary Medallion musical legacy; a gift of national and to create on the piano a richly textured (Hungary) and a Grammy Nomination international importance in music. reduction of an orchestral score at sight. for Best Classical Performance (USA), Throughout his career Tozer resisted He was a superb accompanist and a becoming the only Australian pianist to the frequent calls that he permanently generous collaborator in chamber music. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Contents Price Code an Introduction to Chandos

CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO CHANDOS RECORDS An Introduction to Chandos Records ... ...2 Harpsichord ... ......................................................... .269 A-Z CD listing by composer ... .5 Guitar ... ..........................................................................271 Chandos Records was founded in 1979 and quickly established itself as one of the world’s leading independent classical labels. The company records all over Collections: Woodwind ... ............................................................ .273 the world and markets its recordings from offices and studios in Colchester, Military ... ...208 Violin ... ...........................................................................277 England. It is distributed worldwide to over forty countries as well as online from Brass ... ..212 Christmas... ........................................................ ..279 its own website and other online suppliers. Concert Band... ..229 Light Music... ..................................................... ...281 Opera in English ... ...231 Various Popular Light... ......................................... ..283 The company has championed rare and neglected repertoire, filling in many Orchestral ... .239 Compilations ... ...................................................... ...287 gaps in the record catalogues. Initially focussing on British composers (Alwyn, Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Moeran, Rubbra et al.), it subsequently embraced a much Chamber ... ...245 Conductor Index ... ............................................... .296 -

JOHN IRELAND 70Th Birthday Concert

JOHN IRELAND 70th Birthday ConCert Sir ADRIAN BOULT conductor EILEEN JOYCE piano LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA JOHN IRELAND 70th Birthday ConCert The Henry Wood Promenade Concerts were BBC Symphony Orchestra’s Chief Conductor, inaugurated in 1895 in London’s principal the move from one rostrum to another was concert venue, Queen’s Hall. Following the effected with great smoothness: “I was only hall’s destruction during World War II, the out of work for two or three days,” he liked to BBC Promenade concerts have continued say. For Ireland’s birthday concert he was the ever since at the Royal Albert Hall. The annual ideal choice. Boult’s wide embrace of English summer season is in effect a huge music music had long included Ireland’s music: he festival, drawing the greatest artists and had premièred These things shall be in his BBC orchestras from all over the world. In the days, and in 1936 encouraged the composer to years after the 1939–45 war it became quite turn his Comedy Overture, originally composed usual to celebrate composers’ anniversaries, for brass band, into A London Overture, so sometimes devoting a concert entirely to giving it a wider and more popular following. their music. The concert recorded on this CD, Ireland had a great love of London, revealed in given on 10 September 1949 to mark John such cameos as his picturesque London Pieces Ireland’s 70th birthday, was conducted by Sir for piano with their nostalgic titles ‘Chelsea Adrian Boult (1889–1983). Boult described Reach’ and ‘Soho Forenoons’. A London Overture the composer -

Edith Cowan University

Edith Cowan University Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts Dr Geoffrey Lancaster – Publications Listing 2011 Lancaster, G 2011, 'Joseph Haydn Complete Keyboard Sonatas', Vol. 3, Booklet Notes, Tall Poppies, Sydney, Australia, pp. 1-34. ISBN 9399001002160. Lancaster, G 2011, Joseph Haydn Complete Keyboard Sonatas, Vol. 3, CD, TP 216, Tall Poppies, Sydney, Australia, pp. 64 min 37 sec. Lancaster, G 2011, 'Sonata quasi una fantasia: genre and performance in Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata', Henry Wood Lecture Recital, David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music, London, United Kingdom. Lancaster, G & Hart, D 2011, 'Williams and Haydn: Hidden Meanings', National Gallery of Australia Public Programs, Lecture Recital, James O Fairfax Theatre, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Bundanon Trust, Riversdale, Nowra, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Embassy of the Republic of Finland, Yarralumla, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Woodworks Gallery, Bungendore, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Wesley Music Centre, Forrest, Australia. Lancaster, G 2011, 'Keyboards', TV feature interview, The Collectors, Episode 19, ABC Television, Friday 9 September, Hobart, Australia, pp. 2 min 45 sec. Web. http://www.abc.net.au/tv/collectors/segments/s3314396.htm Lancaster, G 2011, 'Australia's precious ivories', Trust News Australia, vol. 3, no. 5, May, pp. 14-15. ISSN 1835-2316. Lancaster, G 2011, Sonata No. 60 in C, Hob. XVI:50 by Joseph Haydn, (World Premiere performance on Joseph Haydn's restored Longman and Broderip piano), The Cobbe Collection, National Trust, Hatchlands Park, Surrey, United Kingdom Lancaster, G 2011, Sonata No. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection MARIAN FILAR [1-1-1] THIS IS AN INTERVIEW WITH: MF - Marian Filar [interviewee] EM - Edith Millman [interviewer] Interview Dates: September 5, and November 16, 1994, June 16, 1995 Tape one, side one: EM: This is Edith Millman interviewing Professor Marian Filar. Today is Septem- ber 5, 1994. We are interviewing in Philadelphia. Professor Filar, would you tell me where you were born and when, and a little bit about your family? MF: Well, I was born in Warsaw, Poland, before the Second World War. My father was a businessman. He actually wanted to be a lawyer, and he made the exam on the university, but he wasn’t accepted, but he did get an A, but he wasn’t accepted. EM: Could you tell me how large your family was? MF: You mean my general, just my immediate family? EM: Yeah, your immediate family. How many siblings? MF: We were seven children. I was the youngest. I had four brothers and two sis- ters. Most of them played an instrument. My oldest brother played a violin, the next to him played the piano. My sister Helen was my first piano teacher. My sister Lucy also played the piano. My brother Yaacov played a violin. So there was a lot of music there. EM: I just want to interject that Professor Filar is a known pianist. Mr.... MF: Concert pianist. EM: Concert pianist. Professor Filar, could you tell me what your life was like in Warsaw before the war? MF: Well, it was fine. -

Dame Joan Hammond (1912-1966) 2

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID DAME JOAN HILDA HOOD HAMMOND (1912-1996) PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA JULY 2018 Dame Joan Hilda Hood Hammond, DBE, CMG (24 May 1912 – 26 November 1996) was a New Zealand born Australian operatic soprano, singing coach and champion golfer. She toured widely, and became noted particularly for her Puccini roles, and appeared in the major opera houses of the world – the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, La Scala, the Vienna State Opera and the Bolshoi. Her fame in Britain came not just from her stage appearances but from her recordings. A prolific artist, Hammond's repertoire encompassed Verdi, Handel, Tchaikovsky, Massenet, Beethoven, as well as folk song, art song, and lieder. She returned to Australia for concert tours in 1946, 1949 and 1953, and starred in the second Elizabethan Theatre Trust opera season in 1957. She undertook world concert tours between 1946 and 1961. She became patron and a life member of the Victorian Opera Company (since 1976, the Victorian State Opera – VSO), and was the VSO's artistic director from 1971 until 1976 and remained on the board until 1985. Working with the then General Manager, Peter Burch, she invited the young conductor Richard Divall to become the company's Musical Director in 1972. She joined the Victorian Council of the Arts, was a member of the Australia Council for the Arts opera advisory panel, and was an Honorary Life Member of Opera Australia. She was important to the success of both the VSO and Opera Australia. Hammond embarked on a second career as a voice teacher after her performance career ended.