Lumping & Splitting the American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basilinna Genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an Evaluation Based on Molecular Evidence and Implications for the Genus Hylocharis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 797-807, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.35769 The Basilinna genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an evaluation based on molecular evidence and implications for the genus Hylocharis El género Basilinna (Aves: Trochilidae): una evaluación basada en evidencia molecular e implicaciones para el género Hylocharis Blanca Estela Hernández-Baños1 , Luz Estela Zamudio-Beltrán1, Luis Enrique Eguiarte-Fruns2, John Klicka3 and Jaime García-Moreno4 1Museo de Zoología, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70- 399, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 2Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70-275, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 3Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA, USA. 4Amphibian Survival Alliance, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected] Abstract. Hummingbirds are one of the most diverse families of birds and the phylogenetic relationships within the group have recently begun to be studied with molecular data. Most of these studies have focused on the higher level classification within the family, and now it is necessary to study the relationships between and within genera using a similar approach. Here, we investigated the taxonomic status of the genus Hylocharis, a member of the Emeralds complex, whose relationships with other genera are unclear; we also investigated the existence of the Basilinna genus. We obtained sequences of mitochondrial (ND2: 537 bp) and nuclear genes (AK-5 intron: 535 bp, and c-mos: 572 bp) for 6 of the 8 currently recognized species and outgroups. -

Elbroch Et Al 2017 Benefiting from Carrion Provided by Pumas

Biological Conservation 215 (2017) 123–131 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication Vertebrate diversity benefiting from carrion provided by pumas and other MARK subordinate, apex felids ⁎ L. Mark Elbroch , Connor O'Malley, Michelle Peziol, Howard B. Quigley Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Carrion promotes biodiversity and ecosystem stability, and large carnivores provide this resource throughout the Biodiversity year. In particular, apex felids subordinate to other carnivores contribute more carrion to ecological commu- Carnivores nities than other predators. We measured vertebrate scavenger diversity at puma (Puma concolor) kills in the Food webs Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and utilized a model-comparison approach to determine what variables influ- Scavenging enced scavenger diversity (Shannon's H) at carcasses. We documented the highest vertebrate scavenger diversity of any study to date (39 birds and mammals). Scavengers represented 10.9% of local birds and 28.3% of local mammals, emphasizing the diversity of food-web vectors supported by pumas, and the positive contributions of pumas and potentially other subordinate, apex felids to ecological stability. Scavenger diversity at carcasses was most influenced by the length of time the carcass was sampled, and the biological variables, temperature and prey weight. Nevertheless, diversity was relatively consistent across carcasses. We also identified six additional stalk- and-ambush carnivores weighing > 20 kg, that feed on prey larger than themselves, and are subordinate to other predators. Together with pumas, these seven felids may provide distinctive ecological functions through their disproportionate production of carrion and subsequent contributions to biodiversity. -

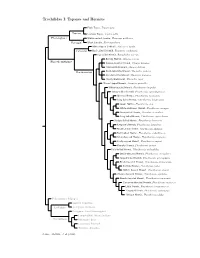

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) Papers in the Biological Sciences

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Waterfowl of North America: Waterfowl Distributions and Migrations in North America Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Waterfowl of North America: Waterfowl Distributions and Migrations in North America" (2010). Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010). 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Waterfowl Distributions and Migrations in North America The species of waterfowl breeding in North America have distribution patterns that collectively reflect the past geologic and ecological histories of this continent. In general, our waterfowl species may be grouped into those that are limited (endemic) to North America, those that are shared between North and South America, and those that are shared with Europe and/or Asia. Of the forty-four species known to breed in continental North America, the resulting grouping of breeding distributions is as follows: Limited to North America: Snow goose (also on Greenland and Wrangel Island) , Ross goose, Canada goose (also on Greenland), wood duck, Amer ican wigeon, black duck, blue-winged teal, redhead, canvasback, ring necked duck, lesser scaup, Labrador duck (extinct), surf scoter, bufflehead, hooded merganser. -

1 AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change Th

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero 02 05 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 1) 03 11 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 2) 04 18 Split Garnet-throated Hummingbird Lamprolaima rhami 05 22 Recognize Amazilia alfaroana as a species not of hybrid origin, thus moving it from Appendix 2 to the main list 06 26 Change the linear sequence of species in the genus Dendrortyx 07 28 Make two changes concerning Starnoenas cyanocephala: (a) assign it to the new monotypic subfamily Starnoenadinae, and (b) change the English name to Blue- headed Partridge-Dove 08 32 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 09 36 Split Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus into two species 10 39 Recognize Great White Heron Ardea occidentalis as a species 11 41 Change the English name of Checker-throated Antwren Epinecrophylla fulviventris to Checker-throated Stipplethroat 12 42 Modify the linear sequence of species in the Phalacrocoracidae 13 49 Modify various linear sequences to reflect new phylogenetic data 1 2020-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 532 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero Background: “Warbler” is perhaps the most widely used catch-all designation for passerines. Its use as a meaningful taxonomic indicator has been defunct for well over a century, as the “warblers” encompass hundreds of thin-billed, insectivorous passerines across more than a dozen families worldwide. This is not itself an issue, as many other passerine names (flycatcher, tanager, sparrow, etc.) share this common name “polyphyly”, and conventions or modifiers are widely used to designate and separate families that include multiple groups. -

90 Records of the “Western Flycatcher” in Florida, With

Florida Field Naturalist 48(3):90–98, 2020. RECORDS OF THE “WESTERN FLYCATCHER” IN FLORIDA, WITH EMPHASIS ON A VOCAL INDIVIDUAL THAT UTTERED CALL-NOTES CONSISTENT WITH PACIFIC-SLOPE FLYCATCHER (Empidonax difficilis) BILL PRANTY,1 DONALD FRASER,2 AND VALERI PONZO3 18515 Village Mill Row, Bayonet Point, Florida 34667-2662 Email: [email protected] 22181 Gulf View Boulevard, Dunedin, Florida 34698 Email: [email protected] 3725 Center Road, Sarasota, Florida 34240 Email: [email protected] In 1989, members of the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list Committee (American Ornithologists’ Union 1989) agreed that the Western Flycatcher (Empidonax difficilis) complex consisted of two species: the Pacific-slope Flycatcher E.( difficilis) and the Cordilleran Flycatcher (E. occidentalis). These former subspecies were elevated to species status based on Johnson (1980) and Johnson and Marten (1988), who reported on apparent genetic and vocal differences and assortative pairing. However, Johnson (1980, 1994) found a mixed population breeding in northern California, and Rush et al. (2009) found hybridization and introgression in southwestern Canada. These discoveries have led some ornithologists to suggest that the two taxa should not have been elevated to separate species. Outside of the hybrid zones, however, Pacific-slope Flycatchers and Cordilleran Flycatchers maintain separate populations, with consistent genetic and vocal differences (Rush et al. 2009). The “Western Flycatcher” was not known to occur in Florida until recently (Robertson and Woolfenden 1992, Stevenson and Anderson 1994, Greenlaw et al. 2014). Pranty (1996) cited a probable report at Gulf Breeze, Santa Rosa County, Florida, on 28 December 1995 by Bob, Lucy, and Scot Duncan. The first verifiable record was thought to have been discovered in 2015, but an earlier, unpublished record, dating to 2004, was posted to eBird ten years later. -

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

Trematoda: Digenea: Plagiorchiformes: Prosthogonimidae

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 8-2003 Whallwachsia illuminata n. gen., n. sp. (Trematoda: Digenea: Plagiorchiformes: Prosthogonimidae) in the Steely-Vented Hummingbird Amazilia saucerrottei (Aves: Apodiformes: Trochilidae) and the Yellow-Olive Flycatcher Tolmomyias sulphurescens (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyraninidae) from the Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Guanacaste, Costa Rica David Zamparo University of Toronto Daniel R. Brooks University of Toronto, [email protected] Douglas Causey University of Alaska Anchorage, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Zamparo, David; Brooks, Daniel R.; and Causey, Douglas, "Whallwachsia illuminata n. gen., n. sp. (Trematoda: Digenea: Plagiorchiformes: Prosthogonimidae) in the Steely-Vented Hummingbird Amazilia saucerrottei (Aves: Apodiformes: Trochilidae) and the Yellow-Olive Flycatcher Tolmomyias sulphurescens (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyraninidae) from the Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Guanacaste, Costa Rica" (2003). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 235. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/235 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for -

Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-Conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number xx76 19xx January XXXX 20212010 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Dedications To Sandra Ogletree, who was an exceptional friend and colleague. Her love for family, friends, and birds inspired us all. May her smile and laughter leave a lasting impression of time spent with her and an indelible footprint in our hearts. To my parents, sister, husband, and children. Thank you for all of your love and unconditional support. To my friends and mentors, Drs. Mitchell Bush, Scott Citino, John Pascoe and Bill Lasley. Thank you for your endless encouragement and for always believing in me. ~ Lisa A. Tell Front cover: Photographic images illustrating various aspects of hummingbird research. Images provided courtesy of Don M. Preisler with the exception of the top right image (courtesy of Dr. Lynda Goff). SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 76 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare- conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Lisa A. Tell and Don M. Preisler Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2021, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (www.depts.ttu.edu/nsrl). -

P0785-P0787.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 785 rows, Zonotrichiaalbicollis. Anim. Behav. 40: 116- singing conspecificsby the Carolina Wren. Auk 181. 98:127-133. HURLY, T. A., L. RATCLIFFE, D. M. WEARY, AND R. Srr~crunro~, S. A. 1991. Singing behaviour of WEISMAN. In press. White-throated Sparrows Black-capped Chickadees (Purus atricapillus). (Zonotrichia albicollis) can perceive pitch change M.Sc.thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, On- using frequency ratio independent of frequency tario, Canada. difference. J. Comp. Psych. WEARY, D. M., R. G. WEISMAN, R. E. LEMON, T. CHIN, MARLER, P. 1960. Bird songsand mate selection, p. AND J. MONGRAIN. 1991. Use of the relative fre- 348-367. In W. E. Lanyon and W. N. Tavolga quencyof notesby Veeries in songrecognition and teds.],Animal soundsand communication. Amer- production. Auk 108:977-98 1. ican Institute of Biological Sciences,Washington, kk&A~, R., ANDL. RAT-. 1989. Absolute and DC. relative pitch processingin Black-capped Chick- NELSON, D. A. 1989. The importance of invariant adees, Parus atricapillus. Anim. Behav. 38:685- and distinctive features in speciesrecognition of 692. bird song. Condor 9 1:120- 130. WEISMAN, R., L. RATCLIFFE,I. JOHNSRUDE,AND T. A. RICE.W. R. 1989. Analvzina tablesof statisticaltests. HURLY. 1990. Absolute and relative pitch pro- Evolution 43:223-225. - duction in the song of the Black-capped Chicka- RICHARDS,D. G. 1981. Estimation of distance of dee. Condor 92: 118-124. The Condor945 ’85481 0 TheCooper Ornithological society I992 SONGS OF TWO MEXICAN POPULATIONS OF THE WESTERN FLYCATCHER EMPIDONAX DZFFZCZLZS COMPLEX’ !!?IEVEN. G. HOWELL Point ReyesBird Observatory,4900 ShorelineHighway, Stinson Beach, CA 94970 RICHARD J. -

S Sapsucker, Cordilleran Flycatcher, and Other Long-Distance Vagrants At

x, illi mson'sS ,psucker, Cordiller n FI ctch r, and other Ion distanc ß aor nts at a Lon Island, N w Yor sto ov r site P.A. Buckley ABSTRACT onceeasy vehicular access was attainedin Six taxa new to--variously--NewYork, the 1964(Buckley 1974). Fast Coast, and easternNorth America are Fire Island is a narrow, 53-kin barrier USGS-PatuxentWildlife Research Center describedand illustrated from Fire Island, islandseparating Great South Bay and the Long Island,New York. WilliamsongSap- mainlandof LongIsland from the Atlantic Box8 @Graduate School ofOceanography sucker, Cordilleran Flycatcher, Cassin's Vireo, Ocean(Figure 1). At theextreme west end o[ Western Warbling-Vireo, Sonora Yel- Fire Island National Seashore(8 krn east o[ UniversityofRhode island lowthroat,and Pink-sidedJunco were cap- Fire Island Inlet and 90 km east-northeast of tured and documentedduring a 1995-2001 New York City), is the areaknown as the mist-nettingstudy examining the ecological LighthouseTract, a 65-hasection of natural Narragansett,Rhode Island 02882 relationshipsamong migratory birds, Deer vegetationwhere the 175-year-oldFire Island Ticks,and Lyme Disease. Two earlier Cassin's Lighthousestands. There, Fire Island nar- (email:[email protected] and Vireo specimensoverlooked by nearly all rowsto 300 m frombay to ocean,with low authors--thefirst for NewJersey and New dune vegetationoceanward, and scattered [email protected])York,respectively--are also illustrated, as is nativePitch Pine (Pinus rigida) groves alter- an earlierWestern Warbling-Vireo from Fire natingwith mixednative deciduous shrub- Island. Identification criteria are discussed at thicketsbayward. Major plant species in the lengthfor all taxa,and the currentstatus of deciduousthickets include Bayberry (Myrica all six as vagrantswithin North Americais pensylvanica),Low Beach Plum (Prunus S.S. -

Notes on Chestnut-Bellied Hummingbird Amazilia

Cotinga 17 Notes on Chestnut-bellied Hum m ingbird Amazilia castaneiventris : a new record for Boyacá, Colom bia Bernabé López-Lanús Cotinga 17 (2002): 51- 52 Amazilia castaneiventris es una especie endémica de Colombia, amenazada de peligro de extinción, de la vertiente oeste del norte de la Cordillera Oriental y Serranía de San Lucas. Su hábitat al parecer es de arbustales y bordes de bosques en zonas semiáridas, lo cual se comprueba con la identificación de un ejemplar en Villa de Leyva, departamento de Boyacá, situada en una región semiárida. El individuo compartía el hábitat con Amazilia tzacatl. Villa de Leyva se encuentra a c. 120 km de la localidad más al sur conocida para la especie, en el mismo altiplano boyacense. Este hábitat en términos generales no se encuentra amenazado, por lo cual la especie podría ser tanto localizada como desapercibida por falta de observaciones. Introduction tzacatl. The black bill was different from adult male Chestnut-bellied Hummingbird Am azilia A. tzacatl, which has a pinkish bill with a black tip castaneiventris is a Colombian endemic3,6 with a (old females and juvenile males of A. tzacatl can restricted distribution5 that occurs very sporadically have black upper mandibles; F. G. Stiles pers. on the western slope of the Cordillera Oriental and comm.). Juvenile plumage was assessed from speci Serranía de San Lucas, at 850–2045 m1,3. It was mens (n =2) at Instituto de Ciencias Nacional, formerly considered Vulnerable1 and at present Universidad Nacional, Bogotá (lack of green throat Endangered2,4, with records from just five localities and breast, with ill-defined greyish underparts), and in the departments of Bolívar (Norosí: Serranía de due to the intensity of green on throat and breast, San Lucas), Santander (Lebrija and Portugal), and and chestnut belly and vent, the Villa de Leyva in Boyacá (Caseteja and Tipacoque)1.