The History of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

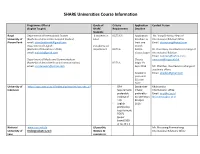

SHARE Universities Course Information

SHARE Universities Course Information Programme Offered Quota of Criteria Application Contact Person (English Taught) SHARE Requirement Deadline Students Royal Department of International Studies 6 students in IELTS 6.5 Application Mr. Vong Chhorvy, Head of University of (Bachelor of Arts in International Studies) total deadline: at International Relation Office Phnom Penh email: [email protected] least one Email: [email protected] Department of English 2 students per month (Bachelor of Education in TEFL) department IELTS 6 before Dr. Oum Ravy, Vice Rector in charge of email: [email protected] classes begin International Relation Email: [email protected], Department of Media and Communication Classes [email protected] (Bachelor of Art in Media and Communication) IELTS 6 begin 19 email: [email protected] Sept 2016 Mr. Phal Des, Vice Rector in charge of academic affairs Academic Email: [email protected] year ends 30 June 2017 University of http://apps.acts.ui.ac.id/index.php/courses/courses_all - GPA September Khairunnisa Indonesia requirement: Intake: International Office preferably preferably Email: [email protected] 3.0 (out of no later than [email protected] 4.0) 30 April - English 2016 proficiency requirement: TOEFL (paper based) 500 or IELTS 5.5 National www.nuol.edu.la (if possible, Mr. Phouvong Phimmakong University of Undergraduate Level: NUOL is to International Relations Office Laos consider to NUOL is under process to develop and launch host in- Email: [email protected] programs-taught in English. Now, there are five coming phoovongphim@gmailcom international programs being considered by the students for University Ministry of Education and Sports. -

University of Yangon History & Location of the University

CHINLONE Connecting Higher Education Institutions for a New Leadership on National Education Erasmus+ KA2 University of Yangon History & Location of the University ° Established on 1st Dec, 1920 ° The first national university in Myanmar ° Yangon, the commercial and former capital city of Myanmar with two campus – Main Campus and Hlaing Campus on Pyay Road Academic Departments 21 Academic Departments headed by a Professor offered undergraduate and postgraduate level courses 13 Arts Departments: Myanmar, English, History, Law, Philosophy, Psychology, Anthropology, Archaeology, International Relations, Political Science, Geography, Oriental Studies and Library & Information Studies 8 Science Departments : Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics, Zoology, Botany, Industrial Chemistry, Geology and Computer Studies Degrees Offered University of Yangon is now an institution for undergraduate & postgraduate studies offering the following degrees: BA& BSc (Dec, 2013) Postgraduate Diploma BA (Hons), BSc (Hons) MA, MSc MRes PhD Faculty Members & Admin Staff Rector 1 Pro-Rector 3 Faculty Staff Professor 47 Associate Professor 45 Lecturer 361 Assistant Lecturer 239 Tutor/Demonstrator 142 Total (Faculty Staff) 834 Total (Admin. Staff ) 546 Total 1383 Administrative Structure of the University of Yangon Rector of the University Dr. Pho Kaung, Ph D Physics, Hokkaido University , Japan Principal Responsibility - taking charge of the all academic and administration of the university Pro-Rectors Dr. Omar Kyaw (LL.D Marine Environmental Law, Hiroshima University, -

View Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT NAVIGATING TOMORROW CONTENTS 1 Chairman’s Message 3 2017 Financial Summary 4 Year in Review 8 Our Community 12 Our Employees 14 Client Profiles 22 2017 Financial Report 24 Relative Stock Prices 25 Bank of Hawaii Locations 26 Managing Committee 28 Board of Directors 29 Shareholder Information NaVIGATING TOMORROW The story of Bank of Hawaii began on Dec. 27, 1897, when Bank of Hawaii became the first chartered and incorporated bank to do business in the Republic of Hawaii. For more than 120 years, we have been helping generations of families, individuals, community organizations and businesses achieve their dreams. The cover image was taken at Bank of Hawaii’s Main Branch grand re-opening in August 2017, when a new Branch of Tomorrow concept was unveiled for its flagship location in downtown Honolulu. Designed with modern technology, digital conveniences and private spaces for personal interactions, the branch features elements of the Hawaiian voyaging canoe, which has always had special meaning for Bank of Hawaii. The Bank of Hawaii canoe, Ulu o ka lā, was commissioned in 2015 and continues to serve as a symbol for the bank. The unique circular overlay pays tribute to the original iron gate at Main Branch. Bank of Hawaii marked 120 years of doing business in 2017, and continues to help its customers explore new possibilities and navigate toward their financial and life goals. View Bank of Hawaii’s 2017 digital summary annual report, featuring videos of our ©2017, Bank of Hawaii Corporation. Bank of Hawaii®, Bankoh® and the Bank of Hawaii logo are Chairman, clients, registered trademarks of Bank of Hawaii. -

Kōkua Creating Good

CONNECTED THROUGH KŌKUA CREATING GOOD. BUILDING STRONGER COMMUNITIES. BANK OF HAWAII COMMUNITY REPORT 2018 workplace where all of our employees feel With nearly half of Hawaii’s people they belong and are able to reach their struggling to get by, the problems full potential to authentically connect outlined in the ALICE report are complex. to the community we serve. Bank of But they’re not insurmountable if we Hawaii has outwardly demonstrated its combine forces to address the issues. support for our LGBTQ community as a One of the most important things for us sponsor of the Honolulu Rainbow Film to do is to realize that the well-being of Festival, and for the first time in 2018, ALICE community members is, in fact, the Honolulu Pride Parade & Festival. our own well-being. We are all connected. I was so proud to march in solidarity Whether we participate from the business, with more than 300 of our employees legislative or philanthropic sectors, we Aloha, and their friends and family alongside each have a vested interest in finding our Bank of Hawaii float in the solutions and ensuring the continued Helping people access a better life Honolulu Pride Parade in October. health of our community. is what Bank of Hawaii does both in a A number of natural disasters in Bank of Hawaii has been helping the professional capacity, and as a caring 2018—volcanic eruptions, typhoons community for over 120 years, and collaborative partner in the community. and tropical storms—brought increased we invite others to partner with our We invest in the innovative vision of challenges to our community, and an efforts. -

O Verseas Partner U Niversities

Overseas Partner Universities [Inter-University Agreements] [Inter-Departmental Agreements] (60 universities in 30 countries/regions) As of 2019 June 1 (28 Faculties, etc. in 16 countries/regions) As of 2019 June 1 Country/Region University Affiliate Since Akita University Department Country/Region University/Department Affiliate Since Indian Institute of Technology Madras 2014 March 2 India VIT University 2015 June 12 Faculty of Engineering, Hasanuddin University 2014 April 23 Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung 2012 July 12 Indonesia Trisakti University 2014 June 10 Asia Faculty of Geological Engineering, Universitas Padjadjaran 2018 October 1 Indonesia Gadjah Mada University 2015 June 8 Universitas Pertamina 2018 August 16 Graduate Faculty of Science, Thailand Kasetsart University 2019 May 29 Padjadjaran University 2019 March 26 School of International Hanbat National University 2001 June 8 Red Sea University Faculty Resource Middle Sudan of Earth Sciences and 2016 December 10 South Korea Wonkwang University 2007 October 12 Sciences East Faculty of Marine Sciences Kangwon National University 2008 March 24 Technical Faculty in Bor, 2016 May 3 Chulalongkorn University 2012 November 28 Serbia University of Belgrade Thailand Suranaree University of Technology 2015 August 17 Europe The AGH University of Chiang Mai University 2015 December 10 Poland Science and Technology 2018 September 19 Lunghwa University of Science 2005 July 15 Faculty of Taiwan and Technology Education and Asia Korea Korean Language School 2019 January 28 National -

The Value of Service SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT 2005 BANK of HAWAII CORPORATION and SUBSIDIARIES

the value of service SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT 2005 BANK OF HAWAII CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES FINANCIAL SUMMARY (DOLLARS IN THOUSANDS EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31 2005 2004 EARNINGS HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Net Income $ 181,561 $ 173,339 Basic Earnings Per Share 3.50 3.26 Diluted Earnings Per Share 3.41 3.08 Dividends Declared Per Share 1.36 1.23 Net Income to Average Total Assets (ROA) 1.81% 1.78% Net Income to Average Shareholders’ Equity (ROE) 24.83% 22.78% Net Interest Margin1 4.37% 4.32% Efficiency Ratio2 53.15% 56.14% AS OF DECEMBER 31 STATEMENT OF CONDITION HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Total Assets $ 10,187,038 $ 9,766,191 Net Loans 6,077,446 5,880,134 Total Deposits 7,907,468 7,564,667 Total Shareholders’ Equity 693,352 814,834 Book Value Per Common Share $ 13.52 $ 14.83 Allowance / Loans and Leases Outstanding 1.48% 1.78% Employees (FTE) 2,585 2,623 Branches and Offices 85 87 Market Price Per Share of Common Stock for the Year Ended December 31: Closing $ 51.54 $ 50.74 High $ 54.44 $ 51.10 Low $ 43.82 $ 40.97 FOR THE QUARTER ENDED DECEMBER 31 EARNINGS HIGHLIGHTS AND PERFORMANCE RATIOS Net Income $ 44,781 $ 46,241 Basic Earnings Per Share 0.88 0.86 Diluted Earnings Per Share 0.86 0.82 Net Income to Average Total Assets (ROA) 1.76% 1.89% Net Income to Average Shareholders’ Equity (ROE) 25.19% 23.63% Net Interest Margin1 4.42% 4.40% Efficiency Ratio2 53.92% 55.37% 1 The net interest margin is defined as net interest income, on a fully-taxable equivalent basis, as a percentage of average earning assets. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): September 4, 2020 FIRST HAWAIIAN, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation) 001-14585 99-0156159 (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 999 Bishop St., 29th Floor Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) (808) 525-7000 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) Not Applicable (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class: Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered: Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share FHB NASDAQ Global Select Market Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

Annual Report 2020 1

ACLS Annual Report 2020 1 AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES Annual Report 2020 2 ACLS Annual Report 2020 Table of Contents Mission and Purpose 1 Message from the President 2 Who We Are 6 Year in Review 12 President’s Report to the Council 18 What We Do 23 Supporting Our Work 70 Financial Statements 84 ACLS Annual Report 2020 1 Mission and Purpose The American Council of Learned Societies supports the creation and circulation of knowledge that advances understanding of humanity and human endeavors in the past, present, and future, with a view toward improving human experience. SUPPORT CONNECT AMPLIFY RENEW We support humanistic knowledge by making resources available to scholars and by strengthening the infrastructure for scholarship at the level of the individual scholar, the department, the institution, the learned society, and the national and international network. We work in collaboration with member societies, institutions of higher education, scholars, students, foundations, and the public. We seek out and support new and emerging organizations that share our mission. We commit to expanding the forms, content, and flow of scholarly knowledge because we value diversity of identity and experience, the free play of intellectual curiosity, and the spirit of exploration—and above all, because we view humanistic understanding as crucially necessary to prototyping better futures for humanity. It is a public good that should serve the interests of a diverse public. We see humanistic knowledge in paradoxical circumstances: at once central to human flourishing while also fighting for greater recognition in the public eye and, increasingly, in institutions of higher education. -

Bank of Hawaii RSSD # 795968

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE August 8, 2016 COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION Bank of Hawaii RSSD # 795968 130 Merchant Street Honolulu, Hawaii, 96813 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, California 94105 NOTE: This document is an evaluation of this institution’s record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low‐ and moderate‐income neighborhoods, consistent with the safe and sound operation of the institution. This evaluation is not, nor should it be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. Bank of Hawaii CRA Public Evaluation Honolulu, Hawaii August 8, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTION RATING ................................................................................................ 1 Institution’s CRA Rating ....................................................................................................... 1 INSTITUTION ........................................................................................................... 2 Description of Institution ..................................................................................................... 2 Scope of Examination .......................................................................................................... 3 CONCLUSIONS WITH RESPECT TO PERFORMANCE TESTS -

Download the Full Essay Here

Shades of sovereignty: racialized power, the United States and the world Paul A. Kramer The segregated diners along Maryland’s Route 40 were always somebody’s problem – mothers packing sandwiches for a daytrip to the nation’s capital, Jim Crow on their minds – but they were not always John F. Kennedy’s problem. That changed in the early 1960s, when African diplomats began arriving to the United States to present their credentials to the United Nations and the White House. Between the high-modernist universalism of the former and the neo-classical, republican universalism of the latter, at just about the place where ambassadors got hungry, lay a scattering of gaudy, ramshackle restaurants straddling an otherwise bleak stretch of highway. As the motoring diplomats discovered to their shock, the diners excluded black people in ways that turned out to be global: whatever their importance to US foreign policy, African economic 1 ministers and cultural attaches received no diplomatic immunity. The incoming Kennedy administration soon confronted an international scandal, as the officials filed formal complaints and US and overseas editors ran with the story. “Human faces, black-skinned and white, angry words and a humdrum reach of U. S. highway,” read an article in Life, “these are the raw stuff of a conflict that reached far out from America in to the world.” Kennedy, reluctant to engage the black freedom struggle except where it intersected with Cold War concerns, established an Office of the Special Protocol Service to mediate: its staff caught flak, spoke to newspapers, and sat down with Route 40’s restaurateurs, diner by diner, making the case that serving black people was in the United States’ global interests. -

ASEAN University Network/ Southeast Asia Engineering Education

ASEAN University Network/ Southeast Asia Engineering Education Development Network AUN/SEED-Net Secretariat Room 109-110, Building 2, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand Tel: +66 2218 6419 to 21 Fax: +66 2218 6418 E-mail: [email protected] Introduction AUN/SEED-Net was established in 2001 as a sub program of AUN. It consists of universities as shown below and aims to establish a region–wide system for advanced research and education by these universities in ASEAN and Japan. The project is mainly supported by the Japanese government through JICA. 26 Member • University of Yangon (UY) Institutions in •National University of Laos • Yangon Technological University ASEAN Countries (NUOL) (YTU) • Hanoi University of Science and Technology 14 Japanese (HUST) Supporting • Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology • Chulalongkorn University (CU) (HCMUT) Universities • King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang • Hokkaido University (Hokkaido) (KMITL) • University of the Philippines – Diliman • Keio University (Keio) • Burapha University (BUU) (UP) • Kyoto University (Kyoto) • Kasetsart University (KU) • De La Salle University (DLSU) • Kyushu University (Kyushu) • Thammasat University (TU) • Mindanao State University – Iligan • Nagoya University (Nagoya) Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT) • National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) • Institute of Technology of • Universiti Brunei Darussalam • Osaka University (Osaka) Cambodia (ITC) (UBD) • Shibaura Institute of • Universiti Teknologi Brunei -

FHB Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation February / March 2021 0 DISCLAIMER Forward-Looking Statements This presentation contains, and from time-to-time in connection with this presentation our management may make, forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. These forward looking statements reflect our views at such time with respect to, among other things, future events and our financial performance. These statements are often, but not always, made through the use of words or phrases such as “may,” “might,” “should,” “could,” “predict,” “potential,” “believe,” “expect,” “continue,” “will,” “anticipate,” “seek,” “estimate,” “intend,” “plan,” “projection,” “would,” “annualized,” and “outlook,” or the negative version of these words or other comparable words or phrases of a future or forward-looking nature. These forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current expectations, estimates and projections about our industry, management’s beliefs and certain assumptions made by management, and any such forward-looking statements are subject to risks, assumptions, estimates and uncertainties that are difficult to predict. Further, statements about the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on our businesses and financial results and conditions may constitute forward-looking statements and are subject to the risk that the actual effects may differ, possibly materially, from what is reflected in those forward-looking statements due to factors and future developments that are uncertain, unpredictable and in many cases beyond our control, including the scope and duration of the pandemic, actions taken by governmental authorities in response to the pandemic, and the direct and indirect impact of the pandemic on our customers, third parties and us.