Military Officer Personnel Management: Key Concepts and Statutory Provisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 6 TITLE 37—PAY and ALLOWANCES of THE

§ 201 TITLE 37—PAY AND ALLOWANCES OF THE UNIFORMED Page 6 SERVICES title and enacting provisions set out as notes under sec- ‘‘Pay grades: assignment to; rear admirals (upper half) tion 308 of this title] may be cited as the ‘Armed Forces of the Coast Guard’’ in item 202. Enlisted Personnel Bonus Revision Act of 1974’.’’ 1980—Pub. L. 96–513, title V, § 506(2), Dec. 12, 1980, 94 Stat. 2918, substituted ‘‘rear admirals (upper half) of SHORT TITLE OF 1963 AMENDMENT the Coast Guard’’ for ‘‘rear admirals of upper half; offi- Pub. L. 88–132, § 1, Oct. 2, 1963, 77 Stat. 210, provided: cers holding certain positions in the Navy’’ in item 202. ‘‘That this Act [enacting sections 310 and 427 of this 1977—Pub. L. 95–79, title III, § 302(a)(3)(C), July 30, title and section 1401a of Title 10, Armed Forces, 1977, 91 Stat. 326, substituted ‘‘precommissioning pro- amending sections 201, 203, 301, 302, 305, 403, and 421 of grams’’ for ‘‘Senior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps’’ this title, sections 1401, 1402, 3991, 6151, 6323, 6325 to 6327, in item 209. 6381, 6383, 6390, 6394, 6396, 6398 to 6400, 6483, and 8991 of 1970—Pub. L. 91–482, § 2F, Oct. 21, 1970, 84 Stat. 1082, Title 10, section 423 of Title 14, Coast Guard, section struck out item 208 ‘‘Furlough pay: officers of Regular 857a of Title 33, Navigation and Navigable Waters, and Navy or Regular Marine Corps’’. section 213a of Title 42, The Public Health and Welfare, 1964—Pub. L. 88–647, title II, § 202(5), Oct. -

The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17

The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17 DAVID IRVING Simon and Schuster: New York This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 i Report errors ii This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 Report errors Jacket design of the original Cas This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 iii Report errors ssell & Co. edition, London, This is the original text of The Destruction of Convoy PQ. as first published in . In order to comply with an order made in the Queen’s Bench division of the High Court in , after the libel action brought by Captain John Broome, a number of passages have been blanked out. In 1981 a revised and updated edition was published by William Kimber Ltd. incorporating the minor changes required by Broome’s solicitors. First published in Great Britain by Cassell & Co. Limited Copyright © David Irving , Electronic edition © Focal Point Publications All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This electronic Internet edition is made avaiolable for leisure reading and research purposes only, and any commercial exploitation of the work without the written consent of the copyright owners will be prosecuted. iv This PDF version: © Focal Point Publications 2002 Report errors INTRODUCTION All books have something which their authors most wish to bring to their readers’ attention. Some authors are successful in this, -

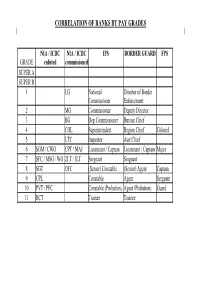

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

Smith, Walter B. Papers.Pdf

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Department Walter Bedell Smith: Papers 66-299--66-402-567; 68-459--68-464; 70-38; 70-45; 70-102--70-104; 70-185-1--70-185-48; 70-280-1--70-280-342 66-299-1 Color Guard at a convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-2 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: Major General John A. Dabney, Commanding General, Fort Jackson; Lt. General A. R. Bolling, Commanding General, the 3rd Army; Captain W.L. Anderson, commanding officer of the Naval ROTC; General Smith, Colonel H.C. Mewshaw, commanding officer of the South Carolina Military District; University President Donald S. Russell; Brigadier General C.M. McQuarris, assistant post commander at Fort Jackson; Colonel Raymond F. Wisehart, commanding officer, Air Force ROTC; and Carter Burgess, assistant to the University president. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-3 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: General Smith, Dr. Orin F. Crow, dean of the University faculty; University President Donald S. Russell; and Dr. L.E. Brubaker, Chaplain of the University. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-4 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. -

Forging the Weapon: the Origins of SHAPE

“Forging the weapon” the origins oF shape La genèse du shape An exhibition celebrating Une exposition qui aura lieu à l’occasion the first public disclosure de la première mise en lecture publique of SHAPE historical documents. de documents historiques du SHAPE. Official launch & cocktail reception Ouverture officielle & réception 7 December 2012 at 11.45 7 décembre 2012 à 11h45 NATO HQ Press Hall Hall de presse de l’OTAN 1705-12 NATO Graphics & Printing www.nato.int/archives/SHAPE The short film ALLIANCE FOR PEACE (1953) and rare film footage chronicling the historical events related to the creation of SHAPE Le court-métrage ALLIANCE FOR PEACE (1953) et des séquences rares qui relatent les événements historiques concernant la genèse de SHAPE. Forging the weapon The origins of SHAPE The NATO Archives and the SHAPE Historical Office would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of SHAPE Records and Registry, the NATO AIM Printing and Graphics Design team, the NATO PDD video editors, the Imperial War Museum, and the archives of the National Geographic Society, all of whom contributed invaluable assistance and material for this exhibition. Les Archives de l’OTAN et le Bureau historique du SHAPE tiennent à expriment toute leur reconnaissance aux Archives et au Bureau d’ordre du SHAPE, à l’équipe Impression et travaux graphiques de l’AIM de l’OTAN, aux monteurs vidéo de la PDD de l’OTAN, à l’Imperial War Museum et au service des archives de la National Geographic Society, pour leur précieuse assistance ainsi que pour le matériel mis à disposition aux fins de cette exposition. -

KZINTI RANK INSIGNIA Amarillo Design Bureau, Inc

Copyright © 2010 KZINTI RANK INSIGNIA Amarillo Design Bureau, Inc. ADMIRAL ADMIRAL ADMIRAL GENERAL ADMIRAL 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank 2nd Rank (ground) 1st Rank (space) COMMODORE COMMODORE BRIGADIER COMMODORE COMMODORE 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank (ground) 2nd Rank 1st Rank CAPTAIN CAPTAIN COLONEL CAPTAIN CAPTAIN 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank (ground) 2nd Rank 1st Rank COMMANDER COMMANDER COMMANDER MAJOR COMMANDER 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank (staff) 2nd Rank (ground) 1st Rank LIEUTENANT LIEUTENANT LIEUTENANT LIEUTENANT LIEUTENANT 5th Rank 4th Rank (Med) 3rd Rank (science) 2nd Rank 1st Rank PILOT PILOT PILOT PILOT (atmospheric) PILOT 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank 2nd Rank 1st Rank NCO NCO NCO SERGEANT NCO 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank 2nd Rank (ground) 1st Rank CREWMAN CREWMAN PRIVATE CREWMAN CREWMAN 5th Rank 4th Rank 3rd Rank (ground) 2nd Rank 1st Rank Kzinti military ranks have both grades (admiral, captain, lieutenant) NCOs (petty officers and sergeants) supervise crewmen. Lieutenants and ranks (admiral 1st rank, lieutenant 4th rank). Ranks within a supervise enlisted personnel. Commanders are department heads grade are earned by time in service, passing certain tests, and/or or deputy heads of larger departments. Captains command starships by achieving some great accomplishment or success (e.g., pilots (or battalions). Commodores (brigadiers in ground forces) command of the 5th rank can be promoted one rank after their first dogfight squadrons (or brigades and divisions). Admirals (or generals) victory, or earn the promotion by experience). Being promoted to command fleets, theaters (or corps and armies). Rank insigia are a higher grade is more difficult; the lowest captain outranks the in branch colors: silver (space, including engineers who are highest commander. -

SHAPE Staff Organisation, 1951-1956

NATO UNCLASSIFIED 1 June 2017 Evolution of the SHAPE Staff Structure, 1951-Present This paper describes the different ways that the staff of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe has been organized, beginning with the original structure of 1951 and continuing through all major reorganizations to the new structure that took effect on 1 August 2010. All of the most senior positions – such as SACEUR and his Deputies – are shown, as are the heads of the various staff divisions. Explanation of Symbols and Acronyms The rank of each post is symbolized by the number of stars worn at that rank. Brigadier General, Commodore, Rear Admiral-Lower Half [U.S.] Major General, Rear Admiral Lieutenant General, Vice Admiral General, Admiral General of the Army, Field Marshal1 The nation selected to fill a particular post at SHAPE is shown by its standard three-letter designation code. Nation codes used in this paper are as follows. BEL Belgium CAN Canada DEU Germany DNK Denmark ESP Spain FRA France GRC Greece GBR United Kingdom ITA Italy NLD Netherlands NOR Norway POL Poland TUR Turkey USA United States 1 There were never any five-star naval positions at SHAPE. The only five-star officers who served at SHAPE were General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, the first SACEUR, and Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, the first DSACEUR. 1 NATO UNCLASSIFIED NATO UNCLASSIFIED The following acronyms are used in this paper, either in the text or on the charts. ACE Allied Command Europe ACOS Assistant Chief of Staff ADEF Air Defence ADP Automated -

Appendix 1 – Crew Lists of HIMS Vostok and Mirnyi

Appendix 1 – Crew Lists of HIMS Vostok and Mirnyi The crew lists were translated from (CL) but without the pay rates. Five names added from Two Seasons or the post-voyage report on crew status (Moller, 1821) are marked with asterisks. The lists do not give patro- nymics and do not identify any cooks. The statement that Nikita Il’in was of ‘officer rank’ (TS, 1: 9) may simply mean that he was a gentleman but not yet a commissioned officer. The crew status report confirms the presence of a third, unidentified servant on Vostok and so corroborates Bellingshausen’s tally of 189 people without the chaplain (TS, 1: 7–9), in short 190 people. Crew of HIMS Vostok Commanding officer: Junior Captain Bellingshausen Captain Lieutenant: Ivan Zavodovskii Lieutenants: Ivan Ignat’ev; Konstantin Torson; Arkadii Leskov Midshipman: Dmitrii Demidov Astronomer: Ivan Simonov* Artist: Pavel Mikhailov* Clerk: Ivan Rezanov Gardemarine: Roman Adams* Navigator: Yakov Paryadin Warrant officers: Andrei Sherkunov; Pëtr Kryukov Master’s mate: Fëdor Vasil’ev Staff surgeon: Yakov Berkh Surgeon’s mate: Ivan Stepanov Quartermasters: Sandash Aneyev; Aleksei Aldygin; Martyn Stepanov; Aleksei Stepanov Butcher: Grigorii Diyakov Drummer: Leontii Churkin Seamen, 1st Class: Semën Trofimov (helmsman); Gubei Abdulov; Stepan Sazanov; Pëtr Maksimov; Kondratii Petrov; Olav Rangoil’; Paul Yakobson; Leon Dubovskii; Semën 214 Crew Lists 215 Gulyayev; Grigorii Anan’in; Grigorii Yelsukov; Stepan Filipov; Sidor Lukin; Matvei Khandukov; Kondratii Borisov; Yeremei Andreyev; Danil Kornev; Sidor -

Handbook on German Army Identification

c rx . zt'fa. "r' w FOREWORD THIS HANDBOOK was prepared at the Military Intelligence Training Center, Camp Ritchie, Maryland, and is designed to provide a ready reference manual for intelligence person- nel in combat operations. The need for such a manual was so pressing that some errors and omissions are anticipated in the current edition. Any suggestions as to additions, or errors noted, should be reported directly to the Comman- dant, Military Intelligence Training Center, for correction in later editions. 513748 -- 43---1 HANDBOOK ON GERMAN ARMY IDENTIFICATION Left to right: Soldier (noncommissioned officer candidate-note silver cord across outer edge of shoulder strap), air force captain (belongs to staff, probably Air Ministry), SS Obergruppenfiihrer Josef Diet- rich (commander SS Division Adolf Hitler and chief of SS Oberabschnitt Ost), Hitler, Reichsfihrer SS Heinrich Himmler (head of the SS and German police). WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, APRIL 9, 1943. HANDBOOK ON GERMAN ARMY IDENTIFICATION SECTION I. General. Paragraph Identification of German military and semi- military organizations --- ______ 1 II. German Order of Battle. Definition--___------------------------_ 2 Purpose and scope --- __ ___---- ----- 3 III. The German Army (Das Deutsche Heer). Uniforms and equipment-------_------- 4 German Army identifications of specialists - - 5 Colors of arms of service (Waffenfarbe) ___- _ _ 6 Enlisted men (Mannschaften)__ _____ 7 Noncommissioned officers (Unteroffiziere) .-- 8 Officers (Offiziere)--------------.--------- 9 German identification -

In Re Yamashita

IN RE YAMASHITA Alston Shepherd Kirk i SCHOUB \a S3a4a IN RE YAMASHITA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Union Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Theology by Alston Shepherd Kirk May 1974 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY Those of us who know war Other than through the medium Of the printed page; Those of us who have seen the thing At close range; Who have looked deep into its bloodshot eyes Behind the bayonet; Who have heard its belching roar In the guns that flamed Their message of death On a hundred fronts, Have learned to hate it With an intense and bitter hatred. Only the soldier knows That war is more than hell. It is a thousand hells In simultaneous erruption. 1 John A. Hayes, An Old Ku£Jiy Bayonet (McDonough, Georgia: Press of the Deep South, 1951), pp. 2-3. We have met the enemy and he is us. Pogo TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. ' 1" II. IN THE MATTER OF YAMASHITA 14 III. A DEFINITION OF CHRISTIAN ETHICAL PERSPECTIVE 53 IV. COMMAND RESPONSIBILITY AS RELATIONSHIP 81 He failed his duty to his . country ...... 88 He failed his duty to his . enemy 91 He failed his duty ... to mankind 94 APPENDIX 1. PRINCIPLES OF' NUREMBERG 98 2. BILL OF PARTICULARS 101 Supplemental Bill of Particulars 113 BIBLIOGRAPHY 122 IV PREFACE This paper has had its genesis, not simply in research, but rather in the practical experiences and serious questions raised by an attempt to carry out a ministry within the institutional framework of the Armed Forces. -

Luftwaffe Maritime Operations in World War Ii

AU/ACSC/6456/2004-2005 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY LUFTWAFFE MARITIME OPERATIONS IN WORLD WAR II: THOUGHT, ORGANIZATION AND TECHNOLOGY by Winston A. Gould, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Instructor: Dr Richard R. Muller Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2005 Distribution A: Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited Ú±®³ ß°°®±ª»¼ λ°±®¬ ܱ½«³»²¬¿¬·±² п¹» ÑÓÞ Ò±ò ðéðìóðïèè Ы¾´·½ ®»°±®¬·²¹ ¾«®¼»² º±® ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·• »•¬·³¿¬»¼ ¬± ¿ª»®¿¹» ï ¸±«® °»® ®»•°±²•»ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ ¬¸» ¬·³» º±® ®»ª·»©·²¹ ·²•¬®«½¬·±²•ô •»¿®½¸·²¹ »¨·•¬·²¹ ¼¿¬¿ •±«®½»•ô ¹¿¬¸»®·²¹ ¿²¼ ³¿·²¬¿·²·²¹ ¬¸» ¼¿¬¿ ²»»¼»¼ô ¿²¼ ½±³°´»¬·²¹ ¿²¼ ®»ª·»©·²¹ ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ò Í»²¼ ½±³³»²¬• ®»¹¿®¼·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»² »•¬·³¿¬» ±® ¿²§ ±¬¸»® ¿•°»½¬ ±º ¬¸·• ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ •«¹¹»•¬·±²• º±® ®»¼«½·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»²ô ¬± É¿•¸·²¹¬±² Ø»¿¼¯«¿®¬»®• Í»®ª·½»•ô Ü·®»½¬±®¿¬» º±® ײº±®³¿¬·±² Ñ°»®¿¬·±²• ¿²¼ λ°±®¬•ô ïîïë Ö»ºº»®•±² Ü¿ª·• Ø·¹¸©¿§ô Í«·¬» ïîðìô ß®´·²¹¬±² Êß îîîðîóìíðîò λ•°±²¼»²¬• •¸±«´¼ ¾» ¿©¿®» ¬¸¿¬ ²±¬©·¬¸•¬¿²¼·²¹ ¿²§ ±¬¸»® °®±ª·•·±² ±º ´¿©ô ²± °»®•±² •¸¿´´ ¾» •«¾¶»½¬ ¬± ¿ °»²¿´¬§ º±® º¿·´·²¹ ¬± ½±³°´§ ©·¬¸ ¿ ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·º ·¬ ¼±»• ²±¬ ¼·•°´¿§ ¿ ½«®®»²¬´§ ª¿´·¼ ÑÓÞ ½±²¬®±´ ²«³¾»®ò ïò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÜßÌÛ íò ÜßÌÛÍ ÝÑÊÛÎÛÜ ßÐÎ îððë îò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÌÇÐÛ ððóððóîððë ¬± ððóððóîððë ìò Ì×ÌÔÛ ßÒÜ ÍËÞÌ×ÌÔÛ ë¿ò ÝÑÒÌÎßÝÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÔËÚÌÉßÚÚÛ ÓßÎ×Ì×ÓÛ ÑÐÛÎßÌ×ÑÒÍ ×Ò ÉÑÎÔÜ ÉßÎ ××æ ë¾ò ÙÎßÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÌØÑËÙØÌô ÑÎÙßÒ×ÆßÌ×ÑÒ ßÒÜ ÌÛÝØÒÑÔÑÙÇ ë½ò ÐÎÑÙÎßÓ ÛÔÛÓÛÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ -

Reform, Foreign Technology, and Leadership in the Russian Imperial and Soviet Navies, 1881–1941

REFORM, FOREIGN TECHNOLOGY, AND LEADERSHIP IN THE RUSSIAN IMPERIAL AND SOVIET NAVIES, 1881–1941 by TONY EUGENE DEMCHAK B.A., University of Dayton, 2005 M.A., University of Illinois, 2007 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Abstract This dissertation examines the shifting patterns of naval reform and the implementation of foreign technology in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union from Alexander III’s ascension to the Imperial throne in 1881 up to the outset of Operation Barbarossa in 1941. During this period, neither the Russian Imperial Fleet nor the Red Navy had a coherent, overall strategic plan. Instead, the expansion and modernization of the fleet was left largely to the whims of the ruler or his chosen representative. The Russian Imperial period, prior to the Russo-Japanese War, was characterized by the overbearing influence of General Admiral Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, who haphazardly directed acquisition efforts and systematically opposed efforts to deal with the potential threat that Japan posed. The Russo-Japanese War and subsequent downfall of the Grand Duke forced Emperor Nicholas II to assert his own opinions, which vacillated between a coastal defense navy and a powerful battleship-centered navy superior to the one at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. In the Soviet era, the dominant trend was benign neglect, as the Red Navy enjoyed relative autonomy for most of the 1920s, even as the Kronstadt Rebellion of 1921 ended the Red Navy’s independence from the Red Army.