Appendix 1 – Crew Lists of HIMS Vostok and Mirnyi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OOB of the Russian Fleet (Kommersant, 2008)

The Entire Russian Fleet - Kommersant Moscow 21/03/08 09:18 $1 = 23.6781 RUR Moscow 28º F / -2º C €1 = 36.8739 RUR St.Petersburg 25º F / -4º C Search the Archives: >> Today is Mar. 21, 2008 11:14 AM (GMT +0300) Moscow Forum | Archive | Photo | Advertising | Subscribe | Search | PDA | RUS Politics Mar. 20, 2008 E-mail | Home The Entire Russian Fleet February 23rd is traditionally celebrated as the Soviet Army Day (now called the Homeland Defender’s Day), and few people remember that it is also the Day of Russia’s Navy. To compensate for this apparent injustice, Kommersant Vlast analytical weekly has compiled The Entire Russian Fleet directory. It is especially topical since even Russia’s Commander-in-Chief compared himself to a slave on the galleys a week ago. The directory lists all 238 battle ships and submarines of Russia’s Naval Fleet, with their board numbers, year of entering service, name and rank of their commanders. It also contains the data telling to which unit a ship or a submarine belongs. For first-class ships, there are schemes and tactic-technical characteristics. So detailed data on all Russian Navy vessels, from missile cruisers to base type trawlers, is for the first time compiled in one directory, making it unique in the range and amount of information it covers. The Entire Russian Fleet carries on the series of publications devoted to Russia’s armed forces. Vlast has already published similar directories about the Russian Army (#17-18 in 2002, #18 in 2003, and #7 in 2005) and Russia’s military bases (#19 in 2007). -

Page 6 TITLE 37—PAY and ALLOWANCES of THE

§ 201 TITLE 37—PAY AND ALLOWANCES OF THE UNIFORMED Page 6 SERVICES title and enacting provisions set out as notes under sec- ‘‘Pay grades: assignment to; rear admirals (upper half) tion 308 of this title] may be cited as the ‘Armed Forces of the Coast Guard’’ in item 202. Enlisted Personnel Bonus Revision Act of 1974’.’’ 1980—Pub. L. 96–513, title V, § 506(2), Dec. 12, 1980, 94 Stat. 2918, substituted ‘‘rear admirals (upper half) of SHORT TITLE OF 1963 AMENDMENT the Coast Guard’’ for ‘‘rear admirals of upper half; offi- Pub. L. 88–132, § 1, Oct. 2, 1963, 77 Stat. 210, provided: cers holding certain positions in the Navy’’ in item 202. ‘‘That this Act [enacting sections 310 and 427 of this 1977—Pub. L. 95–79, title III, § 302(a)(3)(C), July 30, title and section 1401a of Title 10, Armed Forces, 1977, 91 Stat. 326, substituted ‘‘precommissioning pro- amending sections 201, 203, 301, 302, 305, 403, and 421 of grams’’ for ‘‘Senior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps’’ this title, sections 1401, 1402, 3991, 6151, 6323, 6325 to 6327, in item 209. 6381, 6383, 6390, 6394, 6396, 6398 to 6400, 6483, and 8991 of 1970—Pub. L. 91–482, § 2F, Oct. 21, 1970, 84 Stat. 1082, Title 10, section 423 of Title 14, Coast Guard, section struck out item 208 ‘‘Furlough pay: officers of Regular 857a of Title 33, Navigation and Navigable Waters, and Navy or Regular Marine Corps’’. section 213a of Title 42, The Public Health and Welfare, 1964—Pub. L. 88–647, title II, § 202(5), Oct. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

1 17 Massov, A. Ia. the Flag of St Andrew Under the Southern Cross One of the Most Important and Significant Scientific Results

17 Massov, A. Ia. The Flag of St Andrew Under the Southern Cross One of the most important and significant scientific results of the presence of Russian seaman in Australia was the collecting of geological, botanical, and zoological collections, all of which found their way into the museums of Russia. The assembling of collections of so-called rarities constituted one of the duties of certain participants of all the round-the-world expeditions, regardless of the objectives of the latter. The collecting process would continue throughout the voyage. It would certainly not be an exaggeration to assert that, within the context of the early 19th century, items from Australia and Oceania made up one of the most interesting and valuable parts of the material in question. The greater part of these and other such collections were assembled by the mariners themselves; only seldom were items bought or received, already prepared, as gifts from others. This was the case, however with the Herbarium, of a specially rare varieties of Australian flora, presented by Governor Maquarrie to M.N. Vasiliev to be transferred subsequently, as a present, to the dowager empress Maria Fyodorovna. In the second and third decades of the 19th century, large quantities of material suitable for biological collections were still to be found in the immediate vicinity of European settlements. Captain M.N. Vasiliev even found himself obliged to issue an order banning the shooting of birds around the tents of the shore station, set up on the north shore of Port Jackson. The activity was not without some risk for the men undertaking repairs to the sloops. -

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. the Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. The Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956 By Vera Asenova Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Julius Horváth Budapest, Hungary November 2013 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Vera Asenova ………………... ii Abstract This thesis studies international cooperation between a small and a big state in the framework of administered international trade regimes. It discusses the short-term economic goals and long-term institutional effects of international rules on domestic politics of small states. A central concept is the concept of authority in hierarchical relations as defined by Lake, 2009. Authority is granted by the small state in the course of interaction with the hegemonic state, but authority is also utilized by the latter in order to attract small partners and to create positive expectations from cooperation. The main research question is how do small states trade their own authority for economic gains in relations with foreign governments and with local actors. This question is about the relationship between international and domestic hierarchies and the structural continuities that result from international cooperation. The contested relationship between foreign authority and domestic institutions is examined through the experience of Bulgaria under two different international trade regimes – the German economic sphere in the 1930’s and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in the early 1950’s. -

Chapter 2 Friends, Foes and Frenemies in the South

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/48241 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Stoyanov, A. Title: Russia marches South: army reform and battlefield performance in Russia’s Southern campaigns, 1695-1739 Issue Date: 2017-04-26 CHAPTER 2 FRIENDS, FOES AND FRENEMIES IN THE SOUTH If the period from the end of the seventeenth to mid eighteenth century was a chessboard, then opposite Peter’s desire to assert his authority and power over vast territory stood important political and military players who were determined to put an end to his “march”. The following chapter will be divided into several subsections, each dealing with a particular element of the complex geopolitical puzzle that the Pontic region from the first decades of the eighteenth century resembled. Firstly, the focus will be on Russia’s chief adversary – the Ottoman Empire, a foe as determined and as ambitious as the tsarist state itself. Then the main features of the Crimean Khanate, as an element of the overall Ottoman military system, will be defined. However, the Khanate was a player in its own right and pursued its own interests which will also be presented in the current chapter. Next the dissertation will outline the development and the downfall of Safavid’s military and political power, followed by the establishment of a new force under the ambitious and talented Nadir Shah. The subchapter “At the Edge of Empires - the Pontic Frontier and its People” will examine the soldiers of the steppe – Cossacks, Kalmyks, and Nogais, who were an essential element of the social and military ethos of the Pontic frontier and played crucial role in the events, which will be analyzed in detail in the second part of the research. -

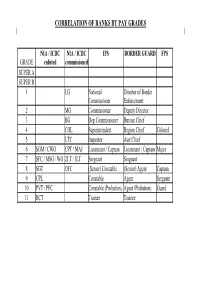

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky №138 September 2019 New Bust to Emperor Alexander III at St. Nicholas Church in Polyarny City A monument to Emperor Alexander III was solemnly opened and consecrated in Polyarny city On the occasion of the 120th anniversary of Polyarny, a solemn opening ceremony of the bust of Emperor Alexander III took place on the territory of St. Nicholas Church. Polyarny is a city in the Murmansk region, located on the shores of the Catherine’s harbour of the Kola Bay of the Barents Sea, about 30 km from Murmansk. The city is home to the Northern Fleet and as such is a closed city. The port was laid down in the summer of 1899 and named Alexandrovsk in honour of Emperor Alexander III. In 1931 it was renamed Polyarny., Parishioners of the church of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker and Rector Archpriest Sergei Mishchenko, initiated and sponsored the bronze bust of the great Russian Emperor Alexander III. The monument was made with donations from parishioners and in February 2019 was delivered from the workshop of Simferopol to Polyarny. The opening and consecration ceremony was conducted by Bishop Tarasiy of the North Sea and Umba. The St. Nicholas Church, with the bust of Emperor Alexander III standing under the bell tower. Stories from Crimea In 2019, there were two extraordinaire reasons to visit Crimea and Yalta in particular - the 100 years anniversary of several members of the Imperial Romanov family, including Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, leaving Russia from Yalta - and 125 years since the repose of Emperor Alexander III in Livadia. -

(Naval) Cadet Corps the Sea Cadet Corps

Sea (Naval) Cadet Corps The Sea Cadet Corps (Russian: Морской кадетский корпус), occasionally translated as the Marine Cadet Corps or the Naval Cadet Corps, is an educational establishment for training Naval officers for the Russian Navy in Saint Petersburg. It is the oldest existing high school in Russia. History The first maritime training school was established in Moscow as the Navigational School in 1701. The School was moved to St Petersburg in 1713 as the Naval Guard Academy. The school was renamed the Sea Cadet Corps on 17 February 1732 and was the key training establishment for officers to the Imperial Russian Navy. In 1800, with the offering of a 'forstmeister' course, the first formal training program for foresters in Russia was established at the academy. On 15 December 1852 the school was enlarged and renamed the Gentry Sea Cadet corps (Морской шляхетный кадетский корпус) with an intake of 360 students. A new building on Vasilievsky Island was also built to house the school. Following the destruction of the building in a fire in 1771 the school transferred to Kronstadt until 1796 when the Czar Paul I ordered a new building in the capital. The school expanded and became the Maritime College in 1867 and renamed again to the Sea Cadet Corps in 1891. The Corps was granted a Royal charter in 1894 and closed after the revolution in 1918 Post Revolution The College reopened in 1918 to train officers for the new Red Navy between 1926 and 1998 the school was named in honour of Mikhail Frunze. The school was merged with another Naval school in 2001 and renamed the Peter the Great Sea Cadet Corps of the St Petersburg Naval Institute. -

The University of Chicago Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMUGGLER STATES: POLAND, LATVIA, ESTONIA, AND CONTRABAND TRADE ACROSS THE SOVIET FRONTIER, 1919-1924 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ANDREY ALEXANDER SHLYAKHTER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2020 Илюше Abstract Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924 What happens to an imperial economy after empire? How do economics, security, power, and ideology interact at the new state frontiers? Does trade always break down ideological barriers? The eastern borders of Poland, Latvia, and Estonia comprised much of the interwar Soviet state’s western frontier – the focus of Moscow’s revolutionary aspirations and security concerns. These young nations paid for their independence with the loss of the Imperial Russian market. Łódź, the “Polish Manchester,” had fashioned its textiles for Russian and Ukrainian consumers; Riga had been the Empire’s busiest commercial port; Tallinn had been one of the busiest – and Russians drank nine-tenths of the potato vodka distilled on Estonian estates. Eager to reclaim their traditional market, but stymied by the Soviet state monopoly on foreign trade and impatient with the slow grind of trade talks, these countries’ businessmen turned to the porous Soviet frontier. The dissertation reveals how, despite considerable misgivings, their governments actively abetted this traffic. The Polish and Baltic struggles to balance the heady profits of the “border trade” against a host of security concerns shaped everyday lives and government decisions on both sides of the Soviet frontier.