Paul Wood, Excerpts From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5x0nd340 No online items Register of the Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection Finding aid prepared by Olga Verhovskoy Dunlop and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2007 Register of the Irwin T. and 98074 1 Shirley Holtzman collection Title: Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection Date (inclusive): 1899-2010 Collection Number: 98074 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 157 manuscript boxes, 9 oversize boxes, 1 card file box, 32 cubic foot boxes(111.4 linear feet) Abstract: Printed matter, writings, letters, photographs, and miscellany, relating to the Russian writers Isaak Babel', Boris Pasternak and Joseph Brodsky. Consists primarily of printed matter by and about Pasternak, Brodsky and Babel'. Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Holtzman, Irwin T creator: Holtzman, Shirley. Access Box 8 restricted; use copies available in Box 4. Box/Folder 22 : 8-15 closed; use copies available in Box/Folder 20 : 1-7. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1998, with subsequent increments received through 2004. Additional increments are expected. An increment was added in 2011. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. -

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin In the 1920s, Berlin was a hub for the transfer of culture between East- ern Europe, Paris, and New York. The German capital hosted Jewish art- ists from Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, where the Kultur-Liga was found- ed in 1918, but forced into line by Soviet authorities in 1924. Among these artists were figures such as Nathan Altman, Henryk Berlewi, El Lissitzky, Marc Chagall, and Issachar Ber Ryback. Once here, they be- came representatives of Modernism. At the same time, they made origi- nal contributions to the Jewish renaissance. Their creations left indelible traces on Europe’s artistic landscape. But the idea of tracing the curiously subtle interaction that exists between the concepts “Jewish” and “mod- ern”... does not seem to me completely unappealing and pointless, especially since the Jews are usually consid- ered adherents of tradition, rigid views, and convention. Arthur Silbergleit1 The work of East European Jewish artists in Germany is closely linked to the question of modernity. The search for new possibilities of expression was especially relevant just before the First World War and throughout the Weimar Republic. Many Jewish artists from Eastern Europe passed through Berlin or took up residence there. One distinguish- ing characteristic of these artists was that on the one hand they were familiar with tradi- tional Jewish forms of life due to their origins; on the other hand, however, they had often made a radical break with this tradition. Contemporary observers such as Kurt Hiller characterised “a modern Jew” at that time as “intellectual, future-oriented, and torn”.2 It was precisely this quality of being “torn” that made East European artists and intellectuals from Jewish backgrounds representative figures of modernity. -

Dialogue of Cultures Under Globalization

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF EDUCATION ST. PETERSBURG INTELLIGENTSIA CONGRESS ST. PETERSBURG UNIVERSITY OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES under the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia DIALOGUE OF CULTURES UNDER GLOBALIZATION PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE: Vol.1 12TH INTERNATIONAL LIKHACHOV SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE May 17–18, 2012 The Conference is held in accordance with The conference, originally called ‘The Days of Sci- the Decree of President of Russia V. V. Putin ence in St. Petersburg University of the Humanities ‘On perpetuating the memory and Social Sciences’ is the 20th in number of Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov’ and the 12th in the status of the International No 587, dated from May 23, 2001 Likhachov Scientific Conference St. Petersburg 2012 ББК 72 Д44 Scientifi c editor A. S. Zapesotsky, Chairman of the Organizing Committee of the International Likhachov Scientifi c Conference, corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, academician of the Russian Academy of Education, Dr. Sc. (Cultural Studies), Professor, Scientist Emeritus of the Russian Federation, Artist Emeritus of the Russian Federation Editor of the English language edition S. R. Abramov, English Chair of St. Petersburg University of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Dr. Sc. (Philology), Professor Recommended to be published by the Editorial and Publishing Council of St. Petersburg University of the Humanities and Social Sciences, minutes No. 7, dated from 28.03.12 Dialogue of Cultures under Globalization. Vol. 1 : Proceedings of the 12th In- Д44 ter national Likha chov Scien tifi c Conference, May 17–18, 2012, St. Peters burg : SPbUHSS, 2012. — 166 p. -

Utopia and Reality in the Art of the October Revolution HISTOREIN

HISTOREIN VOLUME 7 (2007) A critical examination of the artistic tools of Utopia and Reality the October Revolution, particularly in the crucial early years of the civil war up until in the Art of the the establishment of the USSR, promotes a reconsideration of the relation between October Revolution reality and utopian thought in the field of representation. The Revolution naturally encountered many obstacles before finally prevailing. From April 1918 to November 1920 the Bolsheviks fought against foreign mili- tary intervention and the domestic coun- ter-revolution, striving to secure the nec- essary resources that would enable them to achieve their goals. Their military supe- riority was largely based on the organi- sation of the Red Army, while, economi- cally speaking, the militarisation of the economy and the army’s seizure of crops – leading to the impoverishment of the ru- ral population – played a decisive role. On an ideological level, the Bolsheviks strove to spread socialist ideas in order to mobi- lise the population and lead them to join Syrago Tsiara the revolution. State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki Red propaganda was largely directed at il- literate peasants1 and its effectiveness was dependent on the internal organisation and leadership of the Bolshevik party over the working classes and peasants, social forc- es on which Lenin especially relied during the harsh years of the civil war. An attempt to approach the ideologies and emotions of the weaker masses through the strict- ly scientific terms of dialectical material- ism would not have been wise at all. Visual propaganda – with deep routes in Russian culture – did not require the ability to com- 87 HISTOREIN VOLUME 7 (2007) prehend the written word, thus offering an adequate means of attracting broader strata of the population with revolutionary messages. -

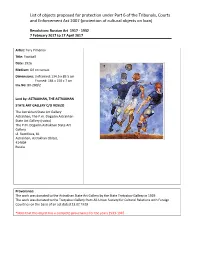

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Yury Pimenov Title: Football Date: 1926 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 134.5 x 89.5 cm Framed: 184 x 150 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/2 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery ul. Sverdlova, 81 Astrakhan, Astrakhan Oblast, 414004 Russia Provenance: The work was donated to the Astrakhan State Art Gallery by the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1929. The work was donated to the Tretyakov Gallery from All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries on the basis of an act dated 23.02.1929 *Note that this object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Ekaterina Zernova Title: Tomato Paste Factory Date: 1929 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 141 x 110 cm Framed: 150 x 120 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/1 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES Saturday - November 16, 2013 RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES 1: SPANISH 17TH C., 'Bust of Saint John the Baptist USD 5,000 - 7,000 SPANISH 17TH C., 'Bust of Saint John the Baptist Holding the Lamb of God', gilted polychrome wood, 85 x 75 x 51 cm (33 1/2 x 29 1/2 x 20 in.), 2: A RUSSIAN CALENDAR ICON, TVER SCHOOL, 16TH C., with 24 USD 20,000 - 30,000 A RUSSIAN CALENDAR ICON, TVER SCHOOL, 16TH C., with 24 various saints including several apostles, arranged in three rows. Egg tempera, gold leaf, and gesso on a wood panel with a kovcheg. The border with egg tempera and gesso on canvas on a wood panel added later. Two insert splints on the back. 47 x 34.7 cm. ( 18 1/2 x 13 3/4 in.), 3: A RUSSIAN ICON OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, S. USHAKOV USD 7,000 - 9,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, S. USHAKOV SCHOOL, LATE 17TH C., egg tempera, gold leaf and gesso on a wood panel with kovcheg. Two insert splints on the back. 54 x 44.1 cm. (21 1/4 x 17 3/8 in.), 4: A RUSSIAN ICON OF SAINT NICHOLAS THE WONDERWORKER, USD 10,000 - 15,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF SAINT NICHOLAS THE WONDERWORKER, MOSCOW SCHOOL, 16TH C., traditionally represented as a Bishop, Nicholas blesses the onlooker with his right hand while holding an open text in his left. The two figures on either side refer to a vision before his election as a Bishop when Nicholas saw the Savior on one side of him holding the Gospels, and the Mother of God on the other one holding out the vestments he would wear as a Bishop. -

From Tsars to Commissars: Russian and Soviet Painting from the Russian Museum

From Tsars to Commissars: Russian and Soviet Painting from the Russian Museum Per Hedström Head of Exhibitions 2 October 2014 – 11 January 2015 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 21 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Photo Credits Every effort has been made by the publisher to is published with generous support from © Palazzo d’Arco, Mantua, inv. 4494/Photo: credit organizations and individuals with regard the Friends of the Nationalmuseum. Nationalmuseum Image Archives, from Domenico to the supply of photographs. Please notify the Fetti 1588/89–1623, Eduard Safarik (ed.), Milan, publisher regarding corrections. Nationalmuseum collaborates with 1996, p. 280, fig. 82 (Figs. 2 and 9A, pp. 13 and Svenska Dagbladet and Grand Hôtel Stockholm. 19) Graphic Design We would also like to thank FCB Fältman & © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow BIGG Malmén. (Fig. 3, p. 13) © bpk/Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/ Layout Cover Illustrations Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut (Figs. 4, 5B, 6B and Agneta Bervokk Domenico Fetti (1588/89–1623), David with the 7B, pp. 14–17) Head of Goliath, c. 1617/20. Oil on canvas, © Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Translation and Language Editing 161 x 99.5 cm. Purchase: The Wiros Fund. Content Program (Figs. 8 and 10B, pp. 18 and Gabriella Berggren, Martin Naylor and Kristin Nationalmuseum, NM 7280. 20) Belkin. © CATS-SMK (Fig. 10A, p. 20) Publisher © Dag Fosse/KODE (p. 25) Publishing Berndt Arell, Director General © Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design/ Ingrid Lindell (Publications Manager) and The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Janna Herder (Editor). Editor Design, Oslo (p. -

Idiot 14 and Tolstoy’S Kreutzer Sonata

Thank you for downloading this free sampler of: SPACES OF CREATIVITY ESSAYS ON RUSSIAN LITERATURE AND THE ARTS Ksana Blank Series: Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures, and History Hardcover | $79.00 | November 2016 | 9781618115409 | 200 pp.; 3 b&w illus.; 13 color illus. SUMMARY In the six essays of this book, Ksana Blank examines affinities among works of nineteenth and twentieth-century Russian literature and their connections to the visual arts and music. Blank demonstrates that the borders of authorial creativity are not stable and absolute, that talented artists often transcend the classifications and paradigms established by critics. Featured in the volume are works by Alexander Pushkin, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Nabokov, Daniil Kharms, Kazimir Malevich, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and Dmitri Shostakovich. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ksana Blank is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University. She is the author of Dostoevsky’s Dialectics and the Problem of Sin (2010). PRAISE “An interdisciplinary creative space is a complex thing. It is home not only to plot, language, structure, but also to whole worlds. In this provocative collection of essays, Ksana Blank shows us some unexpected corners of these worlds: the great Realist novelists shunning the railroad, Shostakovich finding poetry in Dostoevsky, the absurdist Kharms weighing in on a religious controversy, Dobuzhinsky becoming a visual chronicler of Petersburg, Tolstoy anticipating the thinking of Malevich and Nabokov’s nymphet drowning in Pushkinian subtexts. Works we know by heart are estranged and refreshed by these resourceful angles of vision” — Caryl Emerson, Princeton University “Addressing the minor themes in great writers, Ksana Blank demonstrates her talent for telling fascinating stories with surprise conclusions. -

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives EDITED BY LOUISE HARDIMAN AND NICOLA KOZICHAROW To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives Edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Copyright of each chapter is maintained by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

759.47-PAI.Pdf

Archangel Gabriel (Angel withith 9 IVAN NIKITIN. C. 1688—1741 Golden Hair). 12th century Portrait of Peter I. First half of Egg tempera on panel. 48 X 39 * the 1720s Oil on canvas. 55 X 55 (circular) 2 The Miracle of St George. Last quarter of the 15th century 10 IVAN ARGUNOV. 1727—1802 Egg tempera on panel. 58 X 41.5 Portrait of Ekaterina Lobanova- Rostovskaya. 1754 Oil on canvas. 81.5 X 62.5 3 The Presentation in the Temple. First half of the 14th century H IVAN VISHNIAKOV. 1699—1761 Egg tempera on panel. 91 x 66 Portrait of Sarah-Eleanor Fermore. 1750s 4 UNKNOWN ARTIST. Oil on canvas. 138 X 114.5 First quarter of the f8th century Portrait of Yakov Turgenev, 12 FIODOR ROKOTOV. 1730s—1808 Jester of Peter I Portrait of Varvara Surovtseva. Oil on canvas. 105 x 97.5 Second half of the 1780s Oil on canvas. 67.5 X 52 (oval) 5 ROMAN NIKITIN. 1680—1753 Portrait of Maria Stroganova. 13 FIODOR ROKOTOV. 1730s—1808 Between 1721 and 1724 Portrait of Elizaveta Santi. 1785 Oil on canvas. Ill X 90 Oil on canvas. 72.5 X 56 (oval) 14 FIODOR ROKOTOV. 1730s—1808 6 IVAN NIKITIN. C. 1688—1741 Portrait of the Hetman of Portrait of Ivan Orlov. Between the Ukraine. 1720s 1762 and 1765 Oil on canvas. 58.5 x 46.5 Oil on canvas. 76 X 70 15 DMITRY LEVITSKY. 1735—1822 7 ALEXEI ANTROPOV. 1716—1795 Portrait of Praskovya Repnina. Portrait of Fiodor 1781 Krasnoshchokov. 1761 Oil on canvas. -

Академия Художеств 1920-E Началo 1930-X

Музеи россии Академия художеств 1920-e начал o НеизвестНый художНик 4 XX века Натюрморт. 1930-е Холст, масло. 90 ¥ 68 1930-x Учебная работа unknown artist 4 of the 20th century still-life. 1930s Oil on canvas. 90 ¥ 68 cm A class assignment ВероникА БогдАн В НАУчНО-ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛьСКОМ МУЗЕЕ РОССИйСКОй АКАДЕМИИ ХУДО - называться Петроградские государственные свободные художе - жЕСТВ (НИМ РАХ) В САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГЕ чУТь БОЛьШЕ ГОДА ОТКРыТ ЗАЛ, ПО - ственно-учебные мастерские (ПГСХУМ, СВОМАС). В ПГСХУМ по - мимо прежних профессоров начали преподавать А.А. Рылов, А.И. Са- СВящЕННый АКАДЕМИИ ХУДОжЕСТВ В СЛОжНЕйШИй ПЕРИОД ЕЕ винов, А.Т. Матвеев, Л.В. Шервуд, а также художники «левого» на - ИСТОРИИ – 1920-Е – НАчАЛО 1930-Х ГОДОВ. ЗАЛ яВЛяЕТСя ПРОДОЛжЕНИЕМ правления А.А. Андреев, Н.И. Альтман, М.В. Матюшин и другие. ПОСТОяННОй ЭКСПОЗИЦИИ «АКАДЕМИчЕСКИй МУЗЕУМ» И ВМЕСТЕ С ТЕМ Учебные планы и экзамены отменили, с осени 1918 года объявили МОжЕТ РАССМАТРИВАТьСя КАК САМОСТОяТЕЛьНый РАЗДЕЛ. РАЗУМЕЕТСя, свободный прием. Царившие в СВОМАСе в течение четырех лет Н.Н. Пунин, Н.И. Альтман, А.Е. Карев и И.С. Школьник были сто - СОХРАНИВШИйСя ИЗОБРАЗИТЕЛьНый МАТЕРИАЛ НЕ ПОЛНОСТью РАС - ронниками свободы обучения и выступали против давления на ис - КРыВАЕТ ТУ НЕОБычНУю, ПЕСТРУю КАРТИНУ СУщЕСТВОВАНИя В СТЕНАХ кусство любой идеологии. В первый учебный год большие права АКАДЕМИИ В 1920-Х ГОДАХ РАЗНООБРАЗНыХ, ИНОГДА ВЗАИМОИСКЛю - получил студенческий актив – старосты мастерских и курий (жи - вописной, архитектурной, скульптурной), особенно совет старост, чАющИХ НАПРАВЛЕНИй, НО ПОЗВОЛяЕТ РАСШИРИТь НАШИ ПРЕДСТАВЛЕ - ставший высшим органом управления учебным заведением, в ко - НИя ОБ ЭТОМ ПЕРИОДЕ. тором профессора участия не принимали. Уже в июле 1919-го совет старост упразднили, а управление перешло к Учебному совету, Императорская Академия художеств упразднена в апреле 1918 возглавляемому комиссаром, назначаемым Отделом ИЗО Нар - года. -

9780803215474.Pdf

Imagining the Unimaginable studies in war, society, and the military General Editors Peter Maslowski University of Nebraska–Lincoln David Graff Kansas State University Reina Pennington Norwich University Editorial Board D’Ann Campbell Director of Government and Foundation Relations, U.S. Coast Guard Foundation Mark A. Clodfelter National War College Brooks D. Simpson Arizona State University Roger J. Spiller George C. Marshall Professor of Military History U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (retired) Timothy H. E. Travers University of Calgary Arthur Waldron Lauder Professor of International Relations University of Pennsylvania ImagInIng the UnImagInable World War, Modern art, & the Politics of Public culture in russia, 1914–1917 | Aaron J. Cohen ImagInIng the UnImagInable university of nebraska press • lincoln and london Some images have been masked due to copyright limitations. Portions of chapters 1, 2, and 5 previously appeared as “The Dress Rehearsal? Russian Realism and Modernism through War and Revolution” in Rethink- ing the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–05: A Centennial Perspective, vol. 1, ed. Rotem Kowner (Folkstone: Global Oriental, 2007); portions of chapter 5 previously appeared as “Making Modern Art Russian: Artists, Politics, and the Tret’iakov Gallery during the First World War” in Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 2 (2002): 271–81. ¶ © 2008 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska ¶ All rights reserved ¶ Manufactured in the United States of America ¶ ¶ Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data ¶ Cohen, Aaron J. ¶ Imagining the unimagina- ble : World War, modern art, and the politics of public culture in Russia, 1914-1917 / Aaron J. Cohen. ¶ p.