In Art in the First Third of the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5x0nd340 No online items Register of the Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection Finding aid prepared by Olga Verhovskoy Dunlop and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2007 Register of the Irwin T. and 98074 1 Shirley Holtzman collection Title: Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection Date (inclusive): 1899-2010 Collection Number: 98074 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 157 manuscript boxes, 9 oversize boxes, 1 card file box, 32 cubic foot boxes(111.4 linear feet) Abstract: Printed matter, writings, letters, photographs, and miscellany, relating to the Russian writers Isaak Babel', Boris Pasternak and Joseph Brodsky. Consists primarily of printed matter by and about Pasternak, Brodsky and Babel'. Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Holtzman, Irwin T creator: Holtzman, Shirley. Access Box 8 restricted; use copies available in Box 4. Box/Folder 22 : 8-15 closed; use copies available in Box/Folder 20 : 1-7. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman collection, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1998, with subsequent increments received through 2004. Additional increments are expected. An increment was added in 2011. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. -

A Memory of Two Mondays (1955)

Boris Aronson: An Inventory of His Scenic Design Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Title: Boris Aronson Scenic Design Papers Dates: 1939-1977 Extent: 5 boxes, 4 oversize boxes, 47 oversize folders (4.1 linear feet) Abstract: Russian-born painter, sculptor, and most notably set designer Boris Aronson came to America in 1922. The Scenic Design Papers hold original sketches, prints, photographs, and technical drawings showcasing Aronson's set design work on thirty-one plays written and produced between 1939-1977. RLIN Record #: TXRC00-A6 Language: English. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gift and purchase, 1996 (G10669, R13821) Processed by: Helen Baer and Toni Alfau, 1999 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Biographical Sketch Boris Aronson was born in Kiev in 1900, the son of a Jewish rabbi. He came of age in pre-revolutionary Russia in the city that was at the center of Jewish avant-garde theater. After attending art school in Kiev, Aronson served an apprenticeship with the Constructivist designer Alexandre Exter. Under Exter's tutelage and under the influence of the Russian theater directors Alexander Tairov and Vsevolod Meyerhold, whom Aronson admired, he rejected the fashionable realism of Stanislavski in favor of stylized reality and Constructivism. After his apprenticeship he moved to Moscow and then to Germany, where he published two books in 1922, and on their strength was able to obtain a visa to America. In New York he found work in the Yiddish experimental theater designing sets and costumes for, among other venues, the Unser Theatre and the Yiddish Art Theatre. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

The Producers,'' Understands That to Create a Musical -- Good Or Otherwise -- the Appropriate Creative Team Must Be Employed

THEATER/THE TONY AWARDS; A Crash Course in the Worl... http://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/20/arts/theater-the-tony-awar... This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, please click here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. » May 20, 2001 THEATER/THE TONY AWARDS THEATER/THE TONY AWARDS; A Crash Course in the World of Mel By BARRY SINGER EVEN Broadway's most maladroit impresario, Max Bialystock of ''The Producers,'' understands that to create a musical -- good or otherwise -- the appropriate creative team must be employed. For Bialystock, in Mel Brooks's current hit musical, the assured failure of his show, ''Springtime for Hitler,'' is dependent on securing the services of a director named Roger De Bris. ''Is he good?'' inquires Bialystock's ingenuous partner, Leo Bloom, as they head for a rendezvous with De Bris. ''I mean, is he bad?'' ''He stinks,'' Bialystock replies. Shortly thereafter, Bialystock imploringly informs De Bris: ''Roger, I speak for Mr. Bloom and myself when I say that you are the only man in the world who can do justice to 'Springtime for Hitler.' '' For Mr. Brooks, assuring the successful transformation of his 1968 film ''The Producers'' into a Broadway musical required at least one similarly baldfaced overture. ''Two and a half years ago, my husband, Mike Ockrent, and I got a call saying Mel Brooks wanted to meet us,'' Susan Stroman said recently. -

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin In the 1920s, Berlin was a hub for the transfer of culture between East- ern Europe, Paris, and New York. The German capital hosted Jewish art- ists from Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, where the Kultur-Liga was found- ed in 1918, but forced into line by Soviet authorities in 1924. Among these artists were figures such as Nathan Altman, Henryk Berlewi, El Lissitzky, Marc Chagall, and Issachar Ber Ryback. Once here, they be- came representatives of Modernism. At the same time, they made origi- nal contributions to the Jewish renaissance. Their creations left indelible traces on Europe’s artistic landscape. But the idea of tracing the curiously subtle interaction that exists between the concepts “Jewish” and “mod- ern”... does not seem to me completely unappealing and pointless, especially since the Jews are usually consid- ered adherents of tradition, rigid views, and convention. Arthur Silbergleit1 The work of East European Jewish artists in Germany is closely linked to the question of modernity. The search for new possibilities of expression was especially relevant just before the First World War and throughout the Weimar Republic. Many Jewish artists from Eastern Europe passed through Berlin or took up residence there. One distinguish- ing characteristic of these artists was that on the one hand they were familiar with tradi- tional Jewish forms of life due to their origins; on the other hand, however, they had often made a radical break with this tradition. Contemporary observers such as Kurt Hiller characterised “a modern Jew” at that time as “intellectual, future-oriented, and torn”.2 It was precisely this quality of being “torn” that made East European artists and intellectuals from Jewish backgrounds representative figures of modernity. -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

Dialogue of Cultures Under Globalization

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF EDUCATION ST. PETERSBURG INTELLIGENTSIA CONGRESS ST. PETERSBURG UNIVERSITY OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES under the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia DIALOGUE OF CULTURES UNDER GLOBALIZATION PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE: Vol.1 12TH INTERNATIONAL LIKHACHOV SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE May 17–18, 2012 The Conference is held in accordance with The conference, originally called ‘The Days of Sci- the Decree of President of Russia V. V. Putin ence in St. Petersburg University of the Humanities ‘On perpetuating the memory and Social Sciences’ is the 20th in number of Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov’ and the 12th in the status of the International No 587, dated from May 23, 2001 Likhachov Scientific Conference St. Petersburg 2012 ББК 72 Д44 Scientifi c editor A. S. Zapesotsky, Chairman of the Organizing Committee of the International Likhachov Scientifi c Conference, corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, academician of the Russian Academy of Education, Dr. Sc. (Cultural Studies), Professor, Scientist Emeritus of the Russian Federation, Artist Emeritus of the Russian Federation Editor of the English language edition S. R. Abramov, English Chair of St. Petersburg University of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Dr. Sc. (Philology), Professor Recommended to be published by the Editorial and Publishing Council of St. Petersburg University of the Humanities and Social Sciences, minutes No. 7, dated from 28.03.12 Dialogue of Cultures under Globalization. Vol. 1 : Proceedings of the 12th In- Д44 ter national Likha chov Scien tifi c Conference, May 17–18, 2012, St. Peters burg : SPbUHSS, 2012. — 166 p. -

Utopia and Reality in the Art of the October Revolution HISTOREIN

HISTOREIN VOLUME 7 (2007) A critical examination of the artistic tools of Utopia and Reality the October Revolution, particularly in the crucial early years of the civil war up until in the Art of the the establishment of the USSR, promotes a reconsideration of the relation between October Revolution reality and utopian thought in the field of representation. The Revolution naturally encountered many obstacles before finally prevailing. From April 1918 to November 1920 the Bolsheviks fought against foreign mili- tary intervention and the domestic coun- ter-revolution, striving to secure the nec- essary resources that would enable them to achieve their goals. Their military supe- riority was largely based on the organi- sation of the Red Army, while, economi- cally speaking, the militarisation of the economy and the army’s seizure of crops – leading to the impoverishment of the ru- ral population – played a decisive role. On an ideological level, the Bolsheviks strove to spread socialist ideas in order to mobi- lise the population and lead them to join Syrago Tsiara the revolution. State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki Red propaganda was largely directed at il- literate peasants1 and its effectiveness was dependent on the internal organisation and leadership of the Bolshevik party over the working classes and peasants, social forc- es on which Lenin especially relied during the harsh years of the civil war. An attempt to approach the ideologies and emotions of the weaker masses through the strict- ly scientific terms of dialectical material- ism would not have been wise at all. Visual propaganda – with deep routes in Russian culture – did not require the ability to com- 87 HISTOREIN VOLUME 7 (2007) prehend the written word, thus offering an adequate means of attracting broader strata of the population with revolutionary messages. -

A Jewish Art

SUSAN NASHMAN FRAIMAN A Jewish Art It was like coming to the end of the world with no more continents to discover. One must now begin to make habitable the only continents that there are. One must learn to live within the limits of the world. As I see it, this means returning art to the serving of largely human ends. —Arthur C. Danto, in The State of the Art (1987) IN THE BEGINNING , was there Jewish art? 1 The debate about the existence of Jewish art is an old one, starting in the nineteenth century, with the devel - opment of the study of art history, which started almost concurrently with the development of nationalist movements in Europe. Questions of whether each nation has a distinctive style were raised by art historians, and answered in the affirmative. Art historians, however, denied Jews the existence of an art form. Jews, they claimed, were constitutionally unable to produce art—the second commandment was too ingrained in Jewish consciousness. 2 This atti - tude even spilled over to the possibility of creation in other arts—the most notable proponent of this was Wagner, who claimed in “ Das Judenthum in der Musik ” (1850) that the Jews were not only incapable of producing real music, they were incapable of producing real art of any kind. 3 This article will focus on some of artistic activity in the land of Israel, including the founding of Bezalel, offer some examples of artists in Israel working in the “Jewish vein” today, and conclude with a summary of a recent Biennale held in Jerusalem and the new and exciting directions artistic expression by self-defined observant Jews is taking. -

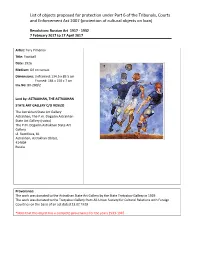

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Yury Pimenov Title: Football Date: 1926 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 134.5 x 89.5 cm Framed: 184 x 150 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/2 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery ul. Sverdlova, 81 Astrakhan, Astrakhan Oblast, 414004 Russia Provenance: The work was donated to the Astrakhan State Art Gallery by the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1929. The work was donated to the Tretyakov Gallery from All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries on the basis of an act dated 23.02.1929 *Note that this object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Ekaterina Zernova Title: Tomato Paste Factory Date: 1929 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 141 x 110 cm Framed: 150 x 120 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/1 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. -

Designers CHAPTI!R SCENERY, COSTUMES, MAKWP, MASKS, WIGS, and HAIR

Image Makers: Designers CHAPTI!R SCENERY, COSTUMES, MAKWP, MASKS, WIGS, AND HAIR Stage-designing should be addressed to [the] eye of the mind. There Is an outer eye that observes, and there Is an inner eye that sees.1 Robert Edmond Jane!, The Dramatic lmagina~·M DesignerS of theatriCal sets, esigners collaborate with directors {and playwrights) td -focus costumes, masks,- puppets, the audiep.ce's attention on the actor in the theatrical space. hair, and wigs r~a1ize tha 0 . They create three-dimensional environments for the actor and production in vfsual terms. make the play's world visible and inte"resting, Sometimes one person (the· They are visual artists scenographer) designs scenery, lighting, and costumes, But in ~ost in who transform space stances today, scenery, costumes, lights, and sound are de~igned by indi and materials into an vidual artists working in collaboration. Imaginative world for actors engaged in human action. THE SCENE DESIGNER Background The seen~ or set designer entered the American theatre more than 100 years ago. The designer's nineteenth-century forerunner was the resident scenic artist, who painted large pieces of scenery !or theatre managers. Scenery's main function in those days was to gl.ve the actor a painted backgroun~ and to Indicate place: a drawing room, garden, etc. Scenic ~ studio~ staffed with specialized artists were set up to· tum out scenery on \ demand. Many of these studios conducted a large mail-order business for 11 ~,.-" r d)> / standard backdrops and scenic pieces.· By the middle of the nineteenth '- '(_a; (1:_ • o'---- _;v- . -

World Scenography World Scenography

WORLD SCENOGRAPHYWORLD This is the first volume in a new series of books members, it draws together theatre production professionals from looking at significant stage design throughout the around the world for mutual learning and benefit. its working world since 1975. this volume, documenting 1975-1990, has commissions are in the areas of scenography, theatre technology, been about four years in the making, and has had contributions publications and communication, history and theory, education, from 100s of people in over 70 countries. Despite this range of and architecture. both of the editors have worked for many years input, it is not possible for it to be encyclopædic, much as the to benefit theatre professionals internationally, through their editors would like. Neither is the series a collection of “greatest activities in OiStAt. hits,” despite the presence of many of the greatest designs of c the period being examined. instead, the object is to present Peter M Kinnon and Eric Fielding probably met each other at the designs that made a difference, designs that mattered, designs banff School of Fine Arts in the early 1980s, when Peter was on of influence. the current editors plan to do two more volumes faculty and Eric was taking Josef Svoboda’s master class there. documenting 1990-2005 and 2005-2015. they then hope that Neither of them remembers the other. they first worked together others will pick up the torch and prepare subsequent volumes in 1993 when Eric was the general editor of the OiStAt lexicon, each decade thereafter. new Theatre Words, and Peter was an English editor.