RESTORING TRADITIONAL SEAFARING and NAVIGATION in GUAM By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trimarans and Outriggers

TRIMARANS AND OUTRIGGERS Arthur Fiver's 12' fibreglass Trimaran with solid plastic foam floats CONTENTS 1. Catamarans and Trimarans 5. A Hull Design 2. The ROCKET Trimaran. 6. Micronesian Canoes. 3. JEHU, 1957 7. A Polynesian Canoe. 4. Trimaran design. 8. Letters. PRICE 75 cents PRICE 5 / - Amateur Yacht Research Society BCM AYRS London WCIN 3XX UK www.ayrs.org office(S)ayrs .org Contact details 2012 The Amateur Yacht Research Society {Founded June, 1955) PRESIDENTS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Lord Brabazon of Tara, Walter Bloemhard. G.B.E., M.C, P.C. VICE-PRESIDENTS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Dr. C. N. Davies, D.sc. John L. Kerby. Austin Farrar, M.I.N.A. E. J. Manners. COMMITTEE BRITISH : Owen Dumpleton, Mrs. Ruth Evans, Ken Pearce, Roland Proul. SECRETARY-TREASURERS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Tom Herbert, Robert Harris, 25, Oakwood Gardens, 9, Floyd Place, Seven Kings, Great Neck, Essex. L.I., N.Y. NEW ZEALAND : Charles Satterthwaite, M.O.W., Hydro-Design, Museum Street, Wellington. EDITORS BRITISH : AMERICAN : John Morwood, Walter Bloemhard "Woodacres," 8, Hick's Lane, Hythe, Kent. Great Neck, L.I. PUBLISHER John Morwood, "Woodacres," Hythc, Kent. 3 > EDITORIAL December, 1957. This publication is called TRIMARANS as a tribute to Victor Tchetchet, the Commodore of the International MultihuU Boat Racing Association who really was the person to introduce this kind of craft to Western peoples. The subtitle OUTRIGGERS is to include the ddlightful little Micronesian canoe made by A. E. Bierberg in Denmark and a modern Polynesian canoe from Rarotonga which is included so that the type will not be forgotten. The main article is written by Walter Bloemhard, the President of the American A.Y.R.S. -

Senate 'Junk Mail' Costs to Be Disclosed That Ended Sept

Metuchen downs Keyport for title, IB MOSTLY CLOUDY Sodal Security Mostly cloudy today through tomorrow. Highs Game will range from 40 to 45 6B both days. The Register Complete forecast 2A. Vol. 108 No. 92 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER...SINCE 1878 MONDAY, DECEMBER 9, 1985 25 CENTS MONDAY Foes seek to halt LOCAL Tinkering pays off Retired inventor's work in electronics plan for high-rise has gained several patents. Now he has a new one for a device that will would be expanded. Each is privately help electronics students. l| BOB NOT owned. The Register The 20-story, 168-unit hotel-condominium HIGHLANDS - Believing the character has been proposed perpendicular to Sandy STATE and ecology of the eastern Bayshore are in Hook Bay. straddling the Atlantic High- jeopardy, opponents of a proposed 20-story lands-Highlands border. Outnumbered hotel-condominium on the Atlantic High- Critics of the proposal, which has become Private treatment centers for lands-Highlands border said yesterday they a sensitive political issue, have become intend to defeat the proposal more vocal in recent months as residents emotionally disturbed Immediately affected oy construction of have become more aware of the two- teen-agers are not prepared to cope the waterfront high-rise and the accompany- borough project. with the growing number of ing proposed townhouses would be a 57-unit Gov. Thomas H. Kean and Rep. James J. youngsters transferred there from mobile home park and area wetlands. But Howard, p-N.J., each have written local New Jersey's overcrowded critics fear its Impact could be far-reaching. -

Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage

束 9mm Proceedings ISBN : 978-4-9909775-1-1 of the International Researchers Forum: Perspectives Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage IRCI Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Published by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage 2 cho, Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802, Japan Tel: +81 – 72 – 275 – 8050 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.irci.jp © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) Published on 10 March 2020 Preface The International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society was organised by the International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) in cooperation with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan and the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties on 17–18 December 2019. -

ORC Special Regulations Mo3 with Life Raft

ISAF OFFSHORE SPECIAL REGULATIONS Including US Sailing Prescriptions www.ussailing.org Extract for Race Category 4 Multihulls JANUARY 2014 - DECEMBER 2015 © ORC Ltd. 2002, all amendments from 2003 © International Sailing Federation, (IOM) Ltd. Version 1-3 2014 Because this is an extract not all paragraph numbers will be present RED TYPE/SIDE BAR indicates a significant change in 2014 US Sailing extract files are available for individual categories and boat types (monohulls and multihulls) at: http://www.ussailing.org/racing/offshore-big-boats/big-boat-safety-at-sea/special- regulations/extracts US Sailing prescriptions are printed in bold, italic letters Guidance notes and recommendations are in italics The use of the masculine gender shall be taken to mean either gender SECTION 1 - FUNDAMENTAL AND DEFINITIONS 1.01 Purpose and Use 1.01.1 It is the purpose of these Special Regulations to establish uniform ** minimum equipment, accommodation and training standards for monohull and multihull yachts racing offshore. A Proa is excluded from these regulations. 1.01.2 These Special Regulations do not replace, but rather supplement, the ** requirements of governmental authority, the Racing Rules and the rules of Class Associations and Rating Systems. The attention of persons in charge is called to restrictions in the Rules on the location and movement of equipment. 1.01.3 These Special Regulations, adopted internationally, are strongly ** recommended for use by all organizers of offshore races. Race Committees may select the category deemed most suitable for the type of race to be sailed. 1.02 Responsibility of Person in Charge 1.02.1 The safety of a yacht and her crew is the sole and inescapable ** responsibility of the person in charge who must do his best to ensure that the yacht is fully found, thoroughly seaworthy and manned by an experienced crew who have undergone appropriate training and are physically fit to face bad weather. -

A Comparative Evaluation of a Hydrofoil-Assisted Trimaran

COMPARATIVE EVALUATION OF A A HYDROFOIL-ASSISTED TRIMARAN Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING By Ryno Moolman Supervisor Prof. T.M. Harms Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Stellenbosch Co-supervisor Dr. G. Migeotte CAE Marine December 2005 Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not previously, in its entirety or in part, been submitted at any University for a degree. Signature of Candidate Date i Abstract This work is concerned with the design and hydrodynamic aspects of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. A design and configuration of a trimaran is evaluated and the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran is effectively compared to the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted catamaran with similar overall displacement and same speed. The performance of the trimaran with different outrigger clearances are also evaluated and compared. The hydrodynamic aspects focuses mainly on the performance and to a lesser extend on the sea-keeping and stability of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. The results were determined by means of experimental testing, theoretical analysis and numerical analysis. The project was initiated as a result of the success of the hydrofoil-assisted catamarans and due to the fact that there does not exist a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran (to the author’s knowledge) where the main focus of the foils is to significantly reduce the resistance. A brief history, recent developments and associated advantages regarding trimarans are discussed. A complete theoretical model is presented to evaluate the lift and drag of the hydrofoils, as well as, the resistance of the trimaran. -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

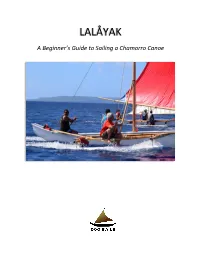

Lalåyak – a Beginner's Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe

LALÅYAK A Beginner’s Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe © 2019 500 Sails. All rights reserved. This project was made possible by support from the Northern Marianas Humanities Council, a non-profit, private corporation funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Northern Marianas Humanities Council will have non-exclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, royalty-free license to exercise all the exclusive rights provided by copyright. Cover photo: Jack Doyle Pictured left to right: Cecilio Raiukiulipiy, Ivan Ilmova, Pete Perez (close canoe); Sophia Perez, Arthur De Oro, Vickson Yalisman (far canoe) Sail between Saipan and Tinian in Tinian Channel. Aguiguan Island in background. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Historic Context ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Sakman Design .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sailing Vocabulary ........................................................................................................................................ -

Pacific Colonisation and Canoe Performance: Experiments in the Science of Sailing

PACIFIC COLONISATION AND CANOE PERFORMANCE: EXPERIMENTS IN THE SCIENCE OF SAILING GEOFFREY IRWIN University of Auckland RICHARD G.J. FLAY University of Auckland The voyaging canoe was the primary artefact of Oceanic colonisation, but scarcity of direct evidence has led to uncertainty and debate about canoe sailing performance. In this paper we employ methods of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic analysis of sailing routinely used in naval architecture and yacht design, but rarely applied to questions of prehistory—so far. We discuss the history of Pacific sails and compare the performance of three different kinds of canoe hull representing simple and more developed forms, and we consider the implications for colonisation and later inter-island contact in Remote Oceania. Recent reviews of Lapita chronology suggest the initial settlement of Remote Oceania was not much before 1000 BC (Sheppard et al. 2015), and Tonga was reached not much more than a century later (Burley et al. 2012). After the long pause in West Polynesia the vast area of East Polynesia was settled between AD 900 and AD 1300 (Allen 2014, Dye 2015, Jacomb et al. 2014, Wilmshurst et al. 2011). Clearly canoes were able to transport founder populations to widely-scattered islands. In the case of New Zealand, modern Mäori trace their origins to several named canoes, genetic evidence indicates the founding population was substantial (Penney et al. 2002), and ancient DNA shows diversity of ancestral Mäori origins (Knapp et al. 2012). Debates about Pacific voyaging are perennial. Fifty years ago Andrew Sharp (1957, 1963) was sceptical about the ability of traditional navigators to find their way at sea and, more especially, to find their way back over long distances with sailing directions for others to follow. -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig. -

Austronesian Diaspora a New Perspective

AUSTRONESIAN DIASPORA A NEW PERSPECTIVE Proceedings the International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora AUSTRONESIAN DIASPORA A NEW PERSPECTIVE Proceedings the International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora PERSPECTIVE 978-602-386-202-3 Gadjah Mada University Press Jl. Grafika No. 1 Bulaksumur Yogyakarta 55281 Telp./Fax.: (0274) 561037 [email protected] | ugmpress.ugm.ac.id Austronesian Diaspora PREFACE OF PUBLISHER This book is a proceeding from a number of papers presented in The International Symposium on Austronesian Diaspora on 18th to 23rd July 2016 at Nusa Dua, Bali, which was held by The National Research Centre of Archaeology in cooperation with The Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums. The symposium is the second event with regard to the Austronesian studies since the first symposium held eleven years ago by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences in cooperation with the International Centre for Prehistoric and Austronesia Study (ICPAS) in Solo on 28th June to 1st July 2005 with a theme of “the Dispersal of the Austronesian and the Ethno-geneses of People in the Indonesia Archipelago’’ that was attended by experts from eleven countries. The studies on Austronesia are very interesting to discuss because Austronesia is a language family, which covers about 1200 languages spoken by populations that inhabit more than half the globe, from Madagascar in the west to Easter Island (Pacific Area) in the east and from Taiwan-Micronesia in the north to New Zealand in the south. Austronesia is a language family, which dispersed before the Western colonization in many places in the world. The Austronesian dispersal in very vast islands area is a huge phenomenon in the history of humankind. -

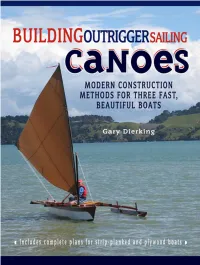

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

ORC Special Regulations Mo3 with Life Raft

ISAF OFFSHORE SPECIAL REGULATIONS Including US Sailing Prescriptions www.ussailing.org Extract for Race Category 3 Multihulls JANUARY 2014 - DECEMBER 2015 © ORC Ltd. 2002, all amendments from 2003 © International Sailing Federation, (IOM) Ltd. Version 1-3 2014 Because this is an extract not all paragraph numbers will be present RED TYPE/SIDE BAR indicates a significant change in 2014 US Sailing extract files are available for individual categories and boat types (monohulls and multihulls) at: http://www.ussailing.org/racing/offshore-big-boats/big-boat-safety-at-sea/special- regulations/extracts US Sailing prescriptions are printed in bold, italic letters Guidance notes and recommendations are in italics The use of the masculine gender shall be taken to mean either gender SECTION 1 - FUNDAMENTAL AND DEFINITIONS 1.01 Purpose and Use 1.01.1 It is the purpose of these Special Regulations to establish uniform ** minimum equipment, accommodation and training standards for monohull and multihull yachts racing offshore. A Proa is excluded from these regulations. 1.01.2 These Special Regulations do not replace, but rather supplement, the ** requirements of governmental authority, the Racing Rules and the rules of Class Associations and Rating Systems. The attention of persons in charge is called to restrictions in the Rules on the location and movement of equipment. 1.01.3 These Special Regulations, adopted internationally, are strongly ** recommended for use by all organizers of offshore races. Race Committees may select the category deemed most suitable for the type of race to be sailed. 1.02 Responsibility of Person in Charge 1.02.1 The safety of a yacht and her crew is the sole and inescapable ** responsibility of the person in charge who must do his best to ensure that the yacht is fully found, thoroughly seaworthy and manned by an experienced crew who have undergone appropriate training and are physically fit to face bad weather.