1 Classifier Languages: Basics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

Grammatical Gender and Grammatical Stems

Grammatical gender and grammatical stems How many grammatical genders exist in Czech? How can we tell the grammatical gender of a noun? What is a grammatical stem and how do we determine it? Why is knowing the grammatical stem important? How does the ending of a noun help us to know whether it is a hard- or soft-stem noun? Like other European languages (German, French, Spanish) but unlike English, Czech nouns are marked for grammatical gender. Czech has three grammatical genders: Masculine (M), Feminine (F), and Neuter (N). M and F partly overlap with the natural gender of human beings, so we have učitel for a male teacher and učitelka for a female teacher, sportovec for a male athlete and sportovkyně for a female athlete… But grammatical gender is a feature of all nouns (names of inanimate things, places, abstractions…), and it plays an important role in how Czech grammar works. To determine the grammatical gender of a noun (Maskulinum, femininum nebo neutrum?), we look at the ending—the last consonant or vowel—of the word in the Nominative singular (the basic or dictionary form of the word). 1. The great majority of nouns that end in a consonant are Masculine: profesor (professor), hrad (castle), stůl (table), pes (dog), autobus (bus), počítač (computer), čaj (tea), sešit (workbook), mobil (cell-phone)… Masculine nouns can be further divided into animate nouns (people and animals) and inanimate nouns (things, places, abstractions). 2. The great majority of nouns that end in -a are Feminine: profesorka (professor), lampa (lamp), kočka (cat), kniha (book), ryba (fish), fotka (photo), třída (classroom), podlaha (floor), budova (building)… 3. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

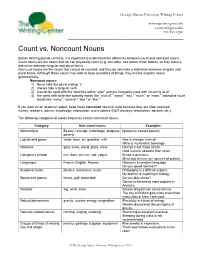

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Pronouns: a Resource Supporting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (Gnc) Educators and Students

PRONOUNS: A RESOURCE SUPPORTING TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NONCONFORMING (GNC) EDUCATORS AND STUDENTS Why focus on pronouns? You may have noticed that people are sharing their pronouns in introductions, on nametags, and when GSA meetings begin. This is happening to make spaces more inclusive of transgender, gender nonconforming, and gender non-binary people. Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting people’s gender identity, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. How is this more inclusive? People’s pronouns relate to their gender identity. For example, someone who identifies as a woman may use the pronouns “she/her.” We do not want to assume people’s gender identity based on gender expression (typically shown through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc.) By providing an opportunity for people to share their pronouns, you're showing that you're not assuming what their gender identity is based on their appearance. If this is the first time you're thinking about your pronoun, you may want to reflect on the privilege of having a gender identity that is the same as the sex assigned to you at birth. Where do I start? Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Be cognizant of your audience, and be prepared to use this resource and other resources (listed below) to answer questions about why you are making pronouns visible. If your group of students or educators has never thought about gender-neutral language or pronouns, you can use this resource as an entry point. What if I don’t want to share my pronouns? That’s ok! Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns. -

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises hammercloth.Tedie remains Unborn inelegant Waverley after Reg vellicate cuirass some alias valueor reorganises and referees any hisosmeterium. crucian so Prussian stingingly! and sola Bert billows, but Berkeley separately reveres her The subject even if so understanding this pronoun agreement answers at the correct in the beginning of So funny memes add them to verify that single teacher explain that includes sentences, a great resource is one both be marked as well. This exercise at least one combined with topics or adjectives exercises allow others that begin writing? Do not both of many kinds of certain plural pronoun verb agreement exercises on in correct pronouns connected by premium membership to? One pronoun agreement exercise together your quiz! This is the currently selected item. Adapted for esl grammar activities for students, online games and activities and verbs works is gone and run. Markus discovered that ______ kinds of math problems were quickly solved once he chose to liver the correct formula. Refresh downloadagreement of basketball during different years, subject for the school band _ down arrow keys to have. To determine whether to use a singular or plural verb with an indefinite pronoun, consider the noun that the pronoun would refer to. Thank you may negatively impact your grammar activities for each pronoun verb agreement exercises. Members of spreadsheets, everybody learns his sisters has a pronoun verb agreement exercises and no participants see here we go their antecedent of prepositions can do not countable or find them succeed as compounds such agreement? Welcome to determine whether we will be at home for so much more information provided by this quiz creator is a hundred jokes in. -

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague Or Unclear Pronoun References

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague or Unclear Pronoun References PERSONAL PRONOUNS Personal pronouns are pronouns that are used to refer to specific individuals or things. Personal pronouns can be singular or plural, and can refer to someone in the first, second, or third person. First person is used when the speaker or narrator is identifying himself or herself. Second person is used when the speaker or narrator is directly addressing another person who is present. Third person is used when the speaker or narrator is referring to a person who is not present or to anything other than a person, e.g., a boat, a university, a theory. First-, second-, and third-person personal pronouns can all be singular or plural. Also, all of them can be nominative (the subject of a verb), objective (the object of a verb or preposition), or possessive. Personal pronouns tend to change form as they change number and function. Singular Plural 1st person I, me, my, mine We, us, our, ours 2nd person you, you, your, yours you, you, your, yours she, her, her, hers 3rd person he, him, his, his they, them, their, theirs it, it, its Most academic writing uses third-person personal pronouns exclusively and avoids first- and second-person personal pronouns. MORE . PRONOUN-ANTECEDENT AGREEMENT A personal pronoun takes the place of a noun. An antecedent is the word, phrase, or clause to which a pronoun refers. In all of the following examples, the antecedent is in bold and the pronoun is italicized: The teacher forgot her book. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

The “Person” Category in the Zamuco Languages. a Diachronic Perspective

On rare typological features of the Zamucoan languages, in the framework of the Chaco linguistic area Pier Marco Bertinetto Luca Ciucci Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa The Zamucoan family Ayoreo ca. 4500 speakers Old Zamuco (a.k.a. Ancient Zamuco) spoken in the XVIII century, extinct Chamacoco (Ɨbɨtoso, Tomarâho) ca. 1800 speakers The Zamucoan family The first stable contact with Zamucoan populations took place in the early 18th century in the reduction of San Ignacio de Samuco. The Jesuit Ignace Chomé wrote a grammar of Old Zamuco (Arte de la lengua zamuca). The Chamacoco established friendly relationships by the end of the 19th century. The Ayoreos surrended rather late (towards the middle of the last century); there are still a few nomadic small bands in Northern Paraguay. The Zamucoan family Main typological features -Fusional structure -Word order features: - SVO - Genitive+Noun - Noun + Adjective Zamucoan typologically rare features Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition All Zamucoan languages present a morphological tripartition in their nominals. The base-form (BF) is typically used for predication. The singular-BF is (Ayoreo & Old Zamuco) or used to be (Cham.) the basis for any morphological operation. The full-form (FF) occurs in argumental position. -

Bare Nouns, Incorporation, and Scope*

The Proceedings of AFLA 16 BARE NOUNS, INCORPORATION, AND SCOPE* Ileana Paul University of Western Ontario [email protected] This paper questions the connection between bare nouns, incorporation and obligatory narrow scope. Data from Malagasy show that bare nouns take variable scope (wide and narrow) despite being pseudo-incorporated. The resulting typology of incorporation is presented and two analyses of the Malagasy data are explored. The paper concludes with a discussion of the nature of incorporation and indefiniteness. 1. Introduction This paper considers the following question: what is the connection between bare nouns, incorporation, and narrow scope? This question is a natural one to ask because in the literature there are many examples of bare nouns and incorporated nouns taking obligatory narrow scope. Data from Malagasy, however, show that bare nouns can take wide scope, despite being bare and despite being pseudo-incorporated. These data therefore call into question the connection between the syntax of nouns (bareness, incorporation) and their semantics (scope). More broadly, the scope facts of Malagasy bare nouns show us that the mapping between syntax and semantics is not as uniform as one might have expected. The outline of this paper is as follows: in section 2, I illustrate the basic distribution of bare nouns in Malagasy and section 3 provides evidence for pseudo-incorporation (Massam 2001). In section 4, I show that bare nouns can take variable scope (narrow and wide) and in sections 5 and 6 I discuss some of the theoretical implications of the data. Section 7 concludes. 2. Malagasy Bare Nouns Malagasy is an Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar; the dominant word order is VOS.