The Moral World of Etty Hillesum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games

© Copyright 2019 Terrence E. Schenold The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Brian M. Reed, Chair Leroy F. Searle Phillip S. Thurtle Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Brian Reed, Professor English The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games explores the complex relationship between digital games and the activity of reflection in the context of the contemporary media ecology. The general aim of the project is to create a critical perspective on digital games that recovers aesthetic concerns for game studies, thereby enabling new discussions of their significance as mediations of thought and perception. The arguments advanced about digital games draw on philosophical aesthetics, media theory, and game studies to develop a critical perspective on gameplay as an aesthetic experience, enabling analysis of how particular games strategically educe and organize reflective modes of thought and perception by design, and do so for the purposes of generating meaning and supporting expressive or artistic goals beyond amusement. The project also provides critical discussion of two important contexts relevant to understanding the significance of this poetic strategy in the field of digital games: the dynamics of the contemporary media ecology, and the technological and cultural forces informing game design thinking in the ludic century. The project begins with a critique of limiting conceptions of gameplay in game studies grounded in a close reading of Bethesda's Morrowind, arguing for a new a "phaneroscopical perspective" that accounts for the significance of a "noematic" layer in the gameplay experience that accounts for dynamics of player reflection on diegetic information and its integral relation to ergodic activity. -

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation Of

A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Stephen Carpenter Patrick Slattery Committee Members, Valerie Hill-Jackson Toby Egan Head of Department, Dennie Smith May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation of Dreams, Memories, and Reflections of the Unconscious Through the Use of Autoethnography/Biography. (May 2011) Antonio Rivera Rosado, B.A., Interamerican University of Puerto Rico; M.Ed., The University of Texas at El Paso Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee, Dr. Stephen Carpenter Dr. Patrick Slattery The purpose of the present study aimed to develop a comprehensive model that measures the autoethnographic/biographic relevance of dreams, memories, and reflections as they relate to understanding the self and others. A dream, memory, and reflection (DMR) ten item questionnaire was constructed using aspects of Freudian, Jungian, and Lacanian Theory of Dream Interpretation. Fifteen dreams, five memories, and five reflections were collected from the participant at the waking episode or during a moment of deep thought. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

No Limit 0 150 None None No Limit 0 150 PG-13 None

Min Age Max Age Game/Event Type (board, Max Number required to Experience Needed to Game Name/Title Brief Description Rule System Name of GM/Presenter Day Start time End Time required to Rating Room Table # card, rpg, panel, etc) of participants play (0 min - play play 99 Max) Panel/Seminar 1000 We Are All Oithlings A discussion of all things Low Life None Andy Hopp Friday 1:00 PM 2:00 PM no limit 0 150 none none Fitness Room 1 An open discussion of these two comic titans and where they stand Panel/Seminar 1001 Marvel vs. DC None Kylan Toles & Ken Rose Thursday 11:00 AM 12:00 PM Fitness Room 1 in comics, movies, and television no limit 0 150 PG-13 none An open discussion regarding the treatment, portrayal, and Dawn Toles, Heather Panel/Seminar 1002 Women and Geekdom marketing to women and how everyone can do their part to bring none Thursday 12:00 PM 1:00 PM Fitness Room 1 Hopp, Jessica Cook no limit 0 150 PG-13 none forth equality in our culture. With Episode VII arriving soon, this is a roundtable for all fans of Ken Rose, Kylan Toles, Panel/Seminar 1003 Let's Talk About Star Wars None Friday 12:00 PM 1:00 PM Fitness Room 1 Star Wars to discuss everything in the universe. Greg Dunn no limit 0 150 None none Transformers, GI Joe, TMNT - so many cartoons from the 80s have Ken Rose, Kylan Toles, Panel/Seminar 1004 80s Small Screen to Big Screen been turned into live action films. -

Etty Hillesum & Thomas Merton

PENNING PATTERNS OF TRANSFORMATION: Etty Hillesum & Thomas Merton by Michael Downey Who is the most significant Christian spiritual writer of the twentieth century? When this question was put to me in the course of my doctoral examination it did not occur to me to advance any other name than that of Gethsemani's most celebrated son. I would stand by my judgment today, even though I see more clearly that Thomas Merton has not been nearly so influential or as widely read in other countries as his American readers are inclined to think. Merton has no rival among Christians in this century when it comes to writing in an engaging and effective fashion about the personal response to the divine initiative. Some may argue that there are others such as the German Jesuit systematic theologian Karl Rahner, or French Dominicans Yves Congar and Marie-Dominique Chenu, or the Swiss Hans Urs von Balthasaar, who are far more significant in the domain of Christian spiritual ity. But the work of Rahner, Congar, Chenu, and von Balthasaar is represen tative of a more systematic mode of reflection and expression. They have adopted an idiom which writers in the field of spirituality are often hesitant to use. Merton was not a systematic theologian nor was he given to reflec tion on the spiritual life in a systematic fashion.1 He was a "spiritual writer" 1. See Anne E. C~rr. A Search for Wisdom and Sptrir: Thomas Merron's Theology of rhe Self (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Noire Dame Press, 1988). 78 Michael Downey Penning Patterns of Transformation 79 primarily concerned with the reality named by that ever-so-slippery term In recent years the writings of another twentieth century figure have "spirituality."2 His attention was given to writing about religious expe drawn considerable attention among Christians and Jews, both in the rience as such, i.e., as religious, and as experience. -

A Collection of Poems and Songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Vaugh Schmidt, Del, "Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs)" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 204. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -------- Waitin' for the blow (A collection of poems and songs) by Del Vaughn Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Approved: Signature redacted for privacy //"' Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1989 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iv POEMS 1 Feeding the Horses 2 The Barnyard 3 Colorado, Summer 1979 5 Arrival 8 Aliens 10 Communicating 12 Home 13 Jeff 15 Waitin' for the Blow 17 Real Surreal 21 Stove Wall 22 Positive 25 Playin' 26 Maybe it's the Music 27 SONGS 31 Have Another (for Colorado) 32 Wake Up 34 Unemployment Blues 36 Players 37 Train We're On 38 Institution 40 iii Farmer's Lament 42 Space Blues 44 You Would Have Made the Day 45 Four Nights in a Row 47 Helpless Bound 49 Carpenter's Blues 50 Hills 51 iv PREFACE Up to the actual point of writing this preface, I have never given much deep thought as to the difference between writing song lyrics and poetry. -

Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 8-3-2006 Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination Eryk Emil Tahvonen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Tahvonen, Eryk Emil, "Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERPETRATORS & POSSIBILITIES: HOLOCAUST DIARIES, RESISTANCE, AND THE CRISIS OF IMAGINATION by ERYK EMIL TAHVONEN Under the Direction of Jared Poley ABSTRACT This thesis examines the way genocide leaves marks in the writings of targeted people. It posits not only that these marks exist, but also that they indicate a type of psychological resistance. By focusing on the ways Holocaust diarists depicted Nazi perpetrators, and by concentrating on the ways language was used to distance the victim from the perpetrator, it is possible to see how Jewish diarists were engaged in alternate and subtle, but nevertheless important, forms of resistance to genocide. The thesis suggest this resistance on the part of victims is similar in many ways to well-known distancing mechanisms employed by perpetrators and that this evidence points to a “crisis of imagination” – for victims and perpetrators alike – in which the capability to envision negation and death, and to identify with the “Other” is detrimental to self-preservation. -

Bibliography of Central European Women's Holocaust Life

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Purdue E-Pubs UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "compara- tive cultural studies." Publications in the Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Bibliographical Article Bibliography of Central European Women's Holocaust Life Writing in English <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/vasvariceushoahbib> Louise O. Vasvári Although the emergence of research on women in the Holocaust dates from the 1980s, the task of integrating the role of women — and that of children — into Holocaust Studies is far from complete, not the least because of the publication of so many women's life writing texts during the last decades, most of which remain virtually unknown. Holocaust scholarship still tends to privilege the Holocaust experience of men as universal and is reluctant to acknowledge testimony that does not follow preconceived gender stereotypes of suitable female behavior or pre- existing narratives of survival (see, e.g., Vasvári, "Women's Holocaust"; Waxman, "Unheard Testimony"; authors of texts of life writing in English are listed in the bibliography; other references are listed in the works cited). -

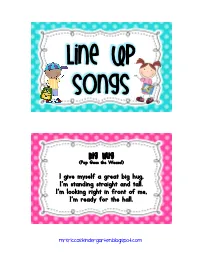

Line up Songs

Line Up Songs Big Hug (Pop Goes the Weasel) I give myself a great big hug, I’m standing straight and tall. I’m looking right in front of me, I’m ready for the hall. Mrsriccaskindergarten.blogspot.com Wiggle I had a little wiggle deep inside of me I tried to make it stop, but it wouldn’t let me be. I pulled out that wiggle and threw it like a ball. And now (teacher’s name) knows, I’m ready for the hall. All Aboard All aboard (line leader)’s train (Line leader)’s train (Line leader)’s train. All aboard (line leader)’s train It’s time to go to _______. Mrsriccaskindergarten.blogspot.com I Am Ready (Frere Jacques) I am ready (children echo) My eyes face front (children echo) Hands behind my back (children echo) Quietly (children echo). Bunny Tail I have a little bunny tail. I’m standing straight and tall. My eyes are facing forward. I’m quiet in the hall. Mrsriccaskindergarten.blogspot.com Finger On Your Lips (If You’re Happy & You Know It) Put your finger on your lips, on your lips, Shh shh Put your finger on your lips, on your lips, Shh shh Put your finger on your lips and don’t let it slip, put your finger on your lips, on your lips, Shh shh. Line Up Cadence Lining up is easy for you When you know just what to do. Feet together, hands by sides. We’ve got spirit, we’ve got pride. Line up 1, 2 Line up 3, 4 Line up…1, 2, 3, 4 Mrsriccaskindergarten.blogspot.com Time to Get in Line (Oh Susanna) When it’s time to get in line, I stand so straight and tall. -

Camp Illahee Songbook

Illahee Songbook Camp Songs Praise Songs Blessings A Day in the Life There are times in my life, when I am so afraid, And I can’t seem to find where I belong. I will love who I am, and learn from my mistakes, For we all have our own special song. Chorus And the life I live, and the love I give, Will flow free like the rivers and the streams, And wherever I go, I will always know, It’s a day in the life of my dreams. I will reach out my hand, to show that I care, And encourage those whose tears they cannot hide, I will learn how to trust, and to ask when I need help, And to talk about my feelings deep inside. Chorus I have dreams, I have songs, that I carry in my heart, As I walk in harmony upon the earth, Like the sun in the sky, the leaves beneath the wind, I will realize the value of my worth. Chorus Annie Mae Annie Mae, where are you going? Upstairs to take a bath. Annie Mae with legs like toothpicks, And a neck like a giraffe. Annie Mae stepped in the bathtub, Annie Mae pulled out the plug, Oh my goodness, Oh my soul, There goes Annie Mae down that hole! Annie Mae, Annie Mae, glub, glub, glub Ash Grove Down yonder green valley where streamlets meander, When twilight is fading, I pensively roam. Or at the bright noontide in solitude wander, Amid the dark shades of the lonely ash grove.