English Grammar Schools Before and After 1902

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

Changes in the Provision of Physical Education for Children Under Twelve Years

Durham E-Theses Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992 Bell, Stephen Gordon How to cite: Bell, Stephen Gordon (1994) Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5534/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHANGES IN THE PROVISION OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN UNDER TWELVE YEARS. 1870-1992 Stephen Gordon Bell The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis presented for the degree of M.A.(Ed,) in the Faculty of Social Science University of Durham 1994 I 0 JUM 199! Abstract A chronological survey over 120 years cannot fail to illustrate the concept of changesas history and change are inter-twined and in some ways synonymous„ Issues arising from political,social,financial,religious, gender and economic constraints affecting the practice and provision of Physical Education for all children under 12 in the state and independent sectors,including those with special needs,are explored within the period.The chapter divisions are broadly determined by the Education Acts of 1870,1902,1918,1944 and 1988 to illustrate developing changes. -

Burnley Council Proposed Business Hub

Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (As Amended) Burnley Council Proposed business hub with conference use Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF Parking & Transport Statement VTC (Highway & Transportation Consultancy) Vision House 29 Howick Park Drive Preston PR1 0LU Tel : 01772 740604 Fax : 01772 741670 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.vtc-consultancy.co.uk 20th December 2017 Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction 2. Site Location and Previous Use 3. Existing Highway Network 4. Proposed Conversion Scheme 5. Traffic and Parking impact of the Proposed Conversion 6. Accessibility of the Proposed Development 7. Conclusions and Recommendation References Site Location Plan Appendix 1 – Road Safety Information Appendix 2 – Proposed Conversion Scheme Appendix 3 – Sustainable Transport Information And LCC Accessibility Assessment Photographs Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction 1.1 This Parking and Transport Statement has been prepared to accompany the planning application for a proposed business hub, with conference facilities, at the former Burnley Grammar School off School Lane in Burnley town centre. The proposed -

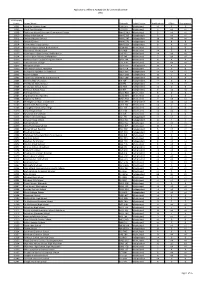

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Founder and First Organising Secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, N.D

British Library: Western Manuscripts MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893-1952) (Add MS 65195-65368) Table of Contents MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893–1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893–1952) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 1 Add MS 65195–65251 A. PAPERS OF INSTITUTIONS, ORGANISATIONS AND COMMITTEES. ([1903–196 2 Add MS 65252–65263 B. SPECIAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65252–65263. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LVIII–LXIX. Letters from (mostly prominent)........................................................................................ 33 Add MS 65264–65287 C. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65264–65287. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LXX–XCIII. General correspondence; 1894–1952,................................................................................. 56 Add MS 65288–65303 D. FAMILY PAPERS. ([1902–1955]).................................................................... 65 Add MS 65304–65362 E. SCRAPBOOKS, NOTEBOOKS AND COLLECTIONS RELATING TO PUBLICATIONS AND LECTURES, ETC. ([1894–1955])......................................................................................................... -

Education Act 1918

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Education Act 1918. (See end of Document for details) Education Act 1918 1918 CHAPTER 39 8 and 9 Geo 5 An Act to make further provision with respect to Education in England and Wales and for purposes connected therewith. [8th August 1918] 1–13 . F1 Textual Amendments F1 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 14 . F2 Textual Amendments F2 S. 14 repealed by Education Act 1973 (c. 16), Sch. 2 Pt. I 15–41 . F3 Textual Amendments F3 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 42 . F4 Textual Amendments F4 S. 42 repealed by Education Act 1944 (c. 31), s. 101(4)(b) and S.R. & O. 1945/255 (1945 I, p. 290) 2 Education Act 1918 (c. 39) Educational Trusts – Document Generated: 2021-03-27 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Education Act 1918. (See end of Document for details) 43, 44. F5 Textual Amendments F5 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 EDUCATIONAL TRUSTS 45 . F6 Textual Amendments F6 S. 45 repealed by Charities Act 1960 (c. 58), Sch. 7 Pt. I 46 . F7 Textual Amendments F7 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. -

The Constitution of the Educational Subject and the Right of Conscience

Access To Thesis. This thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. • A bound copy of every thesis which is accepted as worthy for a higher degree, must be deposited in the University of Sheffield Library, where it will be made available for borrowing or consultation in accordance with University Regulations. • All students registering from 2008–09 onwards are also required to submit an electronic copy of their final, approved thesis. Students who registered prior to 2008–09 may also submit electronically, but this is not required. Peter William Harrison School of Education Author: ........................................................................................................................................................................... Dept: ................................................................................................................................................................. Education and the Constitution of the Subject: A History of the Present 001500700 Thesis Title: ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Registration No: .............................................................. For completion by all students: Submit in print -

Lincolnshire. [ Kelly's

l5AL LINCOLNSHIRE. [ KELLY'S SALESMJ<jN-FISH-COntinned. Louth Savings Bank (C. M. Nesbitt J. P. Holbeach Grammar School (Rev.Ralph Adye Randall John, Fish dock, Great Grimsby actuary; John Hurst J.P. auditor; Richard Ram M.A. head master), Holbeach Weldon John, 80 Stirling street, New Clee, Whitton, clerk), Eastgate, Louth ; open KirtonEndowed Grammar( WilliamCochmne, Great Grimsby wed. from 12 till 1, & fri. & sat. master), Kirton, Boston evenings 7 to 8 in winter & from 8 to 9 Ladies' College (MiS8 Fanny Levien, lally Salesmen-Fruit. 1n• summer principal), 38 St. Peter's hill, Grantham Kirman John, Hope cot. Newmarket, Louth Sleaford Savings Bank (Charles E. Bissill, Lincoln Grammar School (Rev. William actuary; .A. Ingoldby, treasurer; J. C. Weeks Fowler M. A., I<'.L.f'. he11d master; Salesmen-Horae. .Ascough,auditor),open 10 to 12 on monday, Rev. F. A. Williams, N. C. Marris B.A. &: 7 Market place, Sleaford A. W. Kincaid, assistant masters),Lindum Blades Thomll.l', Bardney, Lincoln Spalding Savings Bank (Benjamin Cooper, b~rrace, Lincoln Smith Charle~, 11 Norman street, Lincoln actuary), i!G Hall place, Spalding, open Lincoln High Class Elementary Girls' School Salesmen-Potato. tuesdays 10 to 1 a.m; saturdp.ys 7 to 8 p.m (MiEs Mary Ann Rowe, mistress), rree Stamford Savings Bank (Cepbas Wigmore, school lane, Lincoln Dibble G. F. &: Son~, Blyton, Gainsborough ; sec.), 25 St. Mary's street, Stamford Lincoln Middle School (Rev.Robert Markham & at Smithfielrl mark!.'t, Manchester Hill, head master), Broadgate, Lincoln Kirman John, Hope cot. Newmarket, Louth SAWING, PLANING & MOULD- Lincoln Training College (Rev. Hector ING MILLS. -

Room 261 University of London Senate House London, Wcie 7Hu

n :e a c a d e .1C registrar ROOM 261 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SENATE HOUSE LONDON, WCIE 7HU foi THE EDUCATIONAL POLICIES OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY, 1918-1944 Kevin Jefferys (Bedford College) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ll: JLXN/! ProQuest Number: 10098489 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10098489 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to examine the role played by the Conservative Party in the evolution of the state education system between 1918 and 1944. The early chapters provide a chronological account of ministerial policy and party attitudes towards secondary and elementary education between the wars. This is followed by assessments of the party's approach to the dual system of council and church schools, and to the problems of ' education for employment '. The manner in which Conservative education policy operated locally is then examined with particular reference to the area of London; and the arguments put forward are brought together finally by an analysis of the party's responsibility for, and reaction to, the 1944 Education Act. -

2009 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

Ed 400 399 Author Title Institution Report No Pub Date Available from Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors Abstract Document Resume C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 399 CE 072 717 AUTHOR Marriott, Stuart, Ed.; Hake, Barry J., Ed. TITLE Cultural and Intercultural Experiences in European Adult Education. Essays on Popular and Higher Education since 1890. Leeds Studies in Continuing Education. Cross-Cultural Studies in the Education of Adults, Number 3. INSTITUTION Leeds Univ. (England). Dept. of Adult and Continuing Education. REPORT NO ISBN-0-900960-67-1; ISSN-0965-0342 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 322p.; For a related document in the Cross-Cultural Studies series, see CE 072 716. AVAILABLE FROMLeeds Studies in Continuing Education/Museum of the History of Education, Rm. 14, Parkinson Court, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Andragogy; Case Studies; Continuing Education; Cross Cultural Studies; *Cultural Context; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Exchange; Educational Change; Educational History; Educational. Objectives; Educational Policy; *Educational Practices; *Educational Trends; Extension Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Role of Education IDENTIFIERS *Europe; Folk High Schools; Popular Education ABSTRACT This book contains the following papers from a European research seminar examining the history and theory of cross-cultural communication in adult education: "Introduction" (Stuart Marriott, Barry J. Hake); "Formative Periods in the History of Adult Education: The Role of Social and Cultural Movements in Cross-Cultural Communication" (Barry J. -

Every Marshall Scholar Owes a Great Debt of Gratitude to John Whitaker

Two letters from Alfred Marshall, 1889 and 1919 Rita MacWilliams Tullberg Marshall scholars owe a huge debt of gratitude to John Whitaker for his work in publishing three volumes of extensively annotated Marshall correspondence. Letters from all major and many minor sources are gathered together for the researcher’s convenience and the collection can be regarded as well-nigh exhaustive. It is, therefore, not without a certain rush of excitement that it is possible to report stumbling across odd Marshall letters of interest in unexpected places or among recently-deposited private papers. The first of the following two letters found its way to the British Archives among papers originally belonging to Anne Jemima Clough, the first Principal of the Henry Sidgwick’s house of residence for women coming to Cambridge to study, later to become Newnham College [1] . Dated 1889, Marshall deals with the alarming topic of female franchise. Thirty years later, Marshall wrote to Michael Sadler, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds explaining just why, in his view, Lynda Grier should not be appointed to the vacant Chair of Economics. Women’s franchise [2] Marshall’s early enthusiasm for women education had not included any mention of female franchise. The subject was not one that it was felt wise to raise in the circles round Henry Sidgwick to which Marshall belonged, where the primary aim was to bring the benefits of tertiary education to middle-class women so that they could contribute in a meaningful fashion to the social progress of the nation. Others working in the field of women’s emancipation mid-century were cautious on the subject of suffrage.