Kenneth Cameron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomina Bibliography

Nomina - Bibliography Keith Briggs Last modified 2013-12-18 18:44 This file is automatically generated from Nomina.bib, which is itself automatically generated from Nomina_contents.html by a program I wrote myself (Nomina_to_bibtex_01.py). The file Nom- ina_contents.html is itself generated from a plain ascii .txt file by txt_to_html_01.py. The bibli- ography uses a style file JEPNS_biblatex.sty written by me, together with the biblatex package. There are 319 articles here, covering all volumes to 32 (2009). References Adams, G. B. (1979), ‘Prolegomena to the study of surnames in Ireland’, Nomina 3, pp. 81–94. — (1980), ‘Place-names from pre-Celtic languages in Ireland and Britain’, Nomina 4, pp. 46–63. Adams, G. Brendan (1978), ‘Prolegomena to the study of Irish place-names’, Nomina 2, pp. 45–60. Ames, Jay (1981), ‘Appendix: The nicknames of Jay Ames’, Nomina 5, pp. 80–81. Andrews, J. H. (1992-93), ‘The maps of Robert Lythe as a source for Irish place-names’, Nomina 16, pp. 7–22. Anon. (1978), ‘Papers from the Tenth Conference of the Council for Name Studies in Great Britain and Ireland’, Nomina 2, p. 13. — (1988-89), ‘Two new books by German scholars: Rudiger Fuchs, Das Domesday Book und sein Umfeld. and Jan Gerchow, Die Gedenküberlieferung der Angelsachsen’, Nomina 12, p. 172. — (2003), ‘Society for Name Studies in Britain and Ireland. Twelfth Annual Study Conference: Shetland 2003’, Nomina 26, pp. 119–127. Atkin, M. A. (1988-89), ‘Hollin names in north-west England’, Nomina 12, pp. 77–88. — (1990-91), ‘The medieval exploitation and division of Malham Moor’, Nomina 14, pp. -

Burnley Council Proposed Business Hub

Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (As Amended) Burnley Council Proposed business hub with conference use Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF Parking & Transport Statement VTC (Highway & Transportation Consultancy) Vision House 29 Howick Park Drive Preston PR1 0LU Tel : 01772 740604 Fax : 01772 741670 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.vtc-consultancy.co.uk 20th December 2017 Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction 2. Site Location and Previous Use 3. Existing Highway Network 4. Proposed Conversion Scheme 5. Traffic and Parking impact of the Proposed Conversion 6. Accessibility of the Proposed Development 7. Conclusions and Recommendation References Site Location Plan Appendix 1 – Road Safety Information Appendix 2 – Proposed Conversion Scheme Appendix 3 – Sustainable Transport Information And LCC Accessibility Assessment Photographs Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction 1.1 This Parking and Transport Statement has been prepared to accompany the planning application for a proposed business hub, with conference facilities, at the former Burnley Grammar School off School Lane in Burnley town centre. The proposed -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period. -

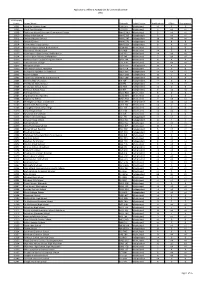

2009 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

Record of the Tenth Conference of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, at the University of Helsinki, 6–11 August 2001

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-03857-7 - Anglo-Saxon England 31 Edited by Michael Lapidge, Malcolm Godden and Simon Keynes Excerpt More information Record of the tenth conference of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, at the University of Helsinki, 6–11 August 2001 I The general theme of the conference was the Anglo-Saxons and the North. The following papers were delivered: Carole Hough, ‘The Structure of Society in the Seventh Century: a New Reading of Æthelberht 12’ Mary P.Richards, ‘The Body as Text in Early Anglo-Saxon Law’ Margaret Clunies Ross, ‘An Anglo-Saxon Runic Coin and its Adventures in Sweden’ Peter J. Lucas, ‘The First Attempts at an Anglo-Saxon Grammar: Sir Henry Spelman and his Contacts with Nordic Scholars’ Barbara Yorke, ‘The “Old North” from the Saxon South in Nineteenth- Century Britain’ Robert E. Bjork, ‘The View from the North: Scandinavian Contributions to Anglo-Saxon Literary Studies’ Patricia Poussa, ‘The “North Folc”: Scandinavian Influence in an Eastern English Dialect Area’ Janne Skaffari, ‘They Take Both Earls and Thralls: Notes on Anglo-Saxon Borrowing of Norse Words’ Kathrin Thier, ‘Ships and their Terminology Between England and the North’ Richard Marsden, ‘Egregious Error: the Importance of Getting It Wrong in the Old English Heptateuch’ Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, ‘Inside, Outside, Conduct and Judgement: Alfred Reads the Regula pastoralis’ Christine Rauer, ‘Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 10861 and the Old English Martyrology’ Lesley Abrams, ‘Place-Names and Settlement History in Viking-Age England’ Debby Banham, ‘Scandinavian Influence on Anglo-Saxon Farming?’ Nicholas Howe, ‘North Looking South: the Anglo-Saxon Construction of Geographical Identity’ Seppo Heikkinen, ‘Bede’s Treatment of Rhythmic Poetry in his De arte metrica’ George H. -

The Afterlives of Bede's Tribal Names in English Place-Names

Chapter 6 The Afterlives of Bede’s Tribal Names in English Place-Names John Baker and Jayne Carroll Bede famously traced the origins of the Anglo-Saxons back to three of the strongest Germanic “tribes”: They came from three very powerful Germanic tribes [de tribus Germani- ae populis fortioribus], the Saxons [Saxonibus], Angles [Anglis], and Jutes [Iutis]. The people of Kent and the inhabitants of the Isle of Wight are of Jutish origin and also those opposite the Isle of Wight, that part of the kingdom of Wessex which is still today called the nation of the Jutes. From the Saxon country, that is, the district now known as Old Saxony, came the East Saxons, the South Saxons, and the West Saxons. Besides this, from the country of the Angles, that is the land between the king- doms of the Jutes and the Saxons, which is called Angulus, came the East Angles, the Middle Angles, the Mercians, and all the Northumbrian race (that is those people who dwell north of the river Humber) as well as the other Anglian tribes.1 Already in the time of Bede, it is clear that these three people-names could be used to denote both continental and insular peoples. Indeed, in Old English (OE) texts, Engle ‘Angle’ is used in several ways: (1) to refer to the inhabitants of Angeln;2 (2) to refer to one of the constituent bodies of the Germanic-speaking inhabitants who arrived in lowland Britain, and who settled, traditionally at least (as in Bede’s Historia), in midland and northern areas of what was to be- come England, and in contrast to Saxons and Jutes (and others);3 (3) the 1 Bede, HE i.15. -

Margaret Joy Gelling (1924–2009)

Margaret Joy Gelling (1924–2009) Margaret Gelling (née Midgely) was born in Manchester on November 29th 1924, but the family (Margaret had two brothers) moved to Sidcup where Margaret attended the grammar school. Thence she went to St Hilda’s College, Oxford where she read English. On graduating in 1945, Professor Dorothy Whitelock suggested that she became a research assistant to the English Place-Name Society as she was the sort of person who could be “sat down in a corner and left to get on with it”. “Getting on with it” was in fact editing the material collected by Doris Stenton for the two EPNS volumes of Oxfordshire which were published in 1953–4. In 1952 she married archaeologist Peter Gelling and they settled in Harborne, Birming- ham, where Peter was a lecturer. Apart from housewifely duties, Margaret was able to pursue her work in place-names. She chose to study North-West Berkshire (now mostly in Oxfordshire) for her doctoral thesis, awarded in 1957, for the very good reason that ‘it was next to Oxfordshire’. She went on to edit the three Berkshire volumes, published in 1973, 1974 and 1976, for the EPNS. This would have familiarised her with the Ock and Upper Thames valleys’ early Anglo-Saxon archaeological sites and the topogra- phical place-names which would be so important in her later thinking. There was a long-held view that -ingas and -ingaham names such as Hastings and Wokingham and the place-names referring to Anglo-Saxon paganism were the earliest names given by the incoming Anglo-Saxons, but Margaret was prepared to challenge this view. -

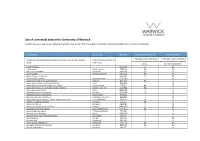

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

Introducing Our Paternal Great Grandmother – Eliza Flack's Family

Introducing our Paternal Great Grandmother – Eliza Flack’s Family Eliza Alice Flack (nee Parker) 1853-1900 By Ted (Edmund) Flack PhD., JP Picture of Market Street Burnley circa 1900 with acknowledgement to Lancashire Telegraph Copyright 2019 Edmund Flack The Parker – Flack Connection Our Paternal Great Grandmother, Eliza Alice Flack, nee Parker (1853-1900) It seems likely that we have heard so little about Eliza Flack, nee Parker, our great grandmother, wife of William Henry Douglas Flack, is because she died in 1900 at just 47 years of age,. Yet from the information available, she was no doubt a remarkable woman. The following family tree explains the Flack family relationship with the Parkers. 1 Eliza Alice Parker was born on 1 October 1853 in Burnley, Lancashire, the first-born child of Richard and Eliza Hartley. Our Great Great Grandmother, Eliza Flack, nee Parker lived at No.10 Hargreaves Street, Burnley in 1860 with her family. Her father was Richard Parker, listed in the 1860 Census as a Wholesale Grocer employing 7 people. The photograph shows the corner of Hargreaves Street Burnley where the Parker Grocery was located before being converted into solicitors’ offices in the 1920s. 2 1861 Census Richard Parker, Head of the Family, aged 27, Wholesale Green Grocer employing 4 men, born Yorkshire, Long Preston. Eliza Parker, Wife, aged 34, born Lancashire Burnley. Eliza Alice Parker, aged 7, born Lancashire, Accrington. Richard Hartley Parker, Son, aged 7 months, Lancashire, Burnley. Thomas Houghton, Boarder, aged 24, Assistant, Lancashire, Blackburn. Martha Ealey, Servant, Aged 25, General servant, Lancashire, Foulridge. Mary Miller, Servant, Aged 54, General servant, Lancashire, Burnley. -

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School -

How People Were Punished in Days Gone By

How people were punished in days gone by In “Peek into the Past” we have examined images of Burnley town centre, the districts and villages around Burnley and a number of its parks. Thinking about what direction I should go in future articles, I found myself, earlier today, in the company of Brierfield Probus where I gave their knowledgeable members a talk entitled “Lancashire’s Calderdale”. As you will know, the Lancashire Calder is the subject of my most recent book, but, when talking to members of Probus, it occurred to me that “Peek” need not only be about buildings, districts and parks. There are an almost limitless number of features of a smaller nature each of which has a story to tell. This thought came to me when my projector was showing an image of the village stocks at Holme in Cliviger. They were there for a purpose. In fact, at one time, every parish or township had to have its stocks, or equivalent. Burnley not only had its stocks but the medieval village also had a whipping post and a ducking stool as well. These, what we think of as quaint features of times past were, when in use, important parts of our punitive system. They constitute some of the means by which miscreants were punished and humiliated, the latter no longer a feature of the system itself. Whether the systems described today were successful or not is not the point. There may be another opportunity to assess that. Similarly, I am not going to say all that much about the individual crimes and misdemeanours for which the stocks, whipping post and ducking stool were thought to be correctives.