Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

Application Report – 20/01379/Ful

APPLICATION REPORT – 20/01379/FUL Validation Date: 22 December 2020 Ward: Astley And Buckshaw Type of Application: Full Planning Proposal: Erection of four dwellings with garages and an additional triple garage adjacent Buckshaw Hall Location: Buckshaw Hall Knight Avenue Buckshaw Village Chorley PR7 7HW Case Officer: Caron Taylor Applicant: Mr Chris Langson Agent: LMP Ltd Consultation expiry: 23 June 2021 Decision due by: 16 February 2021 RECOMMENDATION 1. It is recommended that planning permission is granted subject to conditions and a S106 legal agreement to tie the profits from the sale of the proposed dwellings to the renovation of Buckshaw Hall. SITE DESCRIPTION 2. The application site is located within the original curtilage of Buckshaw Hall, a Grade II* listed manor house. The land surrounding the building and the application site has been developed into Buckshaw Village. The site is surrounded by dwellings with those associated with Buckshaw Village located to the north, east and south and Buckshaw Hall itself located to the west, along with a converted barn. Site access is gained from Knight Avenue to the east. Planning permission and listed building consent were granted initially in 2003 to make the building weatherproof and then in 2006 for the conversion of the barn within the grounds of Buckshaw Hall for ancillary accommodation and changes to Buckshaw Hall itself so it can be brought back into use as a dwelling. DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 3. Buckshaw Hall itself is believed to date in part, from as early as the mid-1600’s with extensive renovation in the late 19th Century. -

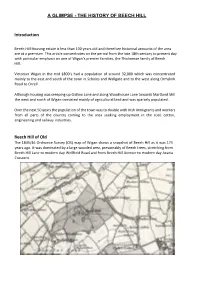

A Glimpse - the History of Beech Hill

A GLIMPSE - THE HISTORY OF BEECH HILL Introduction Beech Hill Housing estate is less than 100 years old and therefore historical accounts of the area are at a premium. This article concentrates on the period from the late 18th century to present day with particular emphasis on one of Wigan’s premier families, the Thicknesse family of Beech Hill. Victorian Wigan in the mid 1800’s had a population of around 32,000 which was concentrated mainly to the east and south of the town in Scholes and Wallgate and to the west along Ormskirk Road to Orrell. Although housing was creeping up Gidlow Lane and along Woodhouse Lane towards Martland Mill the west and north of Wigan consisted mainly of agricultural land and was sparsely populated. Over the next 50 years the population of the town was to double with Irish immigrants and workers from all parts of the country coming to the area seeking employment in the coal, cotton, engineering and railway industries. Beech Hill of Old The 1845/46 Ordnance Survey (OS) map of Wigan shows a snapshot of Beech Hill as it was 175 years ago. It was dominated by a large wooded area, presumably of Beech trees, stretching from Beech Hill Lane to modern day Wellfield Road and from Beech Hill Avenue to modern day Acacia Crescent. In the centre was a large house dating from the late 1600's, called appropriately Beech Hill Hall. The hall was in its own grounds with a formal garden, parkland and large ponds. By overlaying a modern map over the 1845 version the location of Beech Hill Hall can be pinpointed as being off Ascroft Avenue in the Cherry Grove cul-de-sac. -

ON the WORK of MID DURHAM AAP… March 2018

A BRIEF ‘HEADS UP’ ON THE WORK OF MID DURHAM AAP… March 2018 WELCOME Welcome to your March edition of the AAPs e-bulletin / e-newsletter. In this month’s edition we will update you on: - Mid Durham’s next Board meeting - Community Snippets - Partner Updates For more detailed information on all our meetings and work (notes, project updates, members, etc) please visit our web pages at www.durham.gov.uk/mdaap or sign up to our Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/pages/Mid-Durham-Area-Action- Partnership-AAP/214188621970873 MID DURHAM AAP - March Board Meeting The Mid Durham AAP will be holding its next Board meeting on Wednesday 14th March 2018 at 6pm in New Brancepeth Village Hall, Rock Terrace, New Brancepeth, DH7 7EP On the agenda will be presentation on the proposed Care Navigator Programme which is a person-centred approach which uses signposting and information to help primary care patients and their carers move through the health and social care system. There will also be several Area Budget projects coming to the Board including the Deernees Paths and an Environment Improvement Pot that if approved will start later this year. We ask that you register your attendance beforehand by contacting us on 07818510370 or 07814969392 or 07557541413 or email middurhamaap.gov.uk. Community Snippets Burnhope – The Community Centre is now well underway and is scheduled for completion at the end of May. The builder – McCarricks, have used a drone to take photos… Butsfield Young Farmers – Similar to Burnhope, the young Farmers build is well under way too and is due for completion in mid-March… Lanchester Loneliness Project – Several groups and residents in Lanchester are working together to tackle social isolation within their village. -

Changes in the Provision of Physical Education for Children Under Twelve Years

Durham E-Theses Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992 Bell, Stephen Gordon How to cite: Bell, Stephen Gordon (1994) Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5534/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHANGES IN THE PROVISION OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN UNDER TWELVE YEARS. 1870-1992 Stephen Gordon Bell The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis presented for the degree of M.A.(Ed,) in the Faculty of Social Science University of Durham 1994 I 0 JUM 199! Abstract A chronological survey over 120 years cannot fail to illustrate the concept of changesas history and change are inter-twined and in some ways synonymous„ Issues arising from political,social,financial,religious, gender and economic constraints affecting the practice and provision of Physical Education for all children under 12 in the state and independent sectors,including those with special needs,are explored within the period.The chapter divisions are broadly determined by the Education Acts of 1870,1902,1918,1944 and 1988 to illustrate developing changes. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton Richardson, Martin Howard How to cite: Richardson, Martin Howard (1998) The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN COUNTY DURHAM, 1944-1974, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FERRYHILL AND CHILTON MARTIN HOWARD RICHARDSON This thesis grew out of a single question: why should a staunch Labour Party stronghold like County Durham open a grammar school in 1964 when the national Party was so firmly committed to comprehensivization? The answer was less easy to find than the question was to pose. -

Burnside College

Burnside College DETERMINED ADMISSION POLICY FOR MIDDLE AND HIGH LEARNING TRUST SCHOOLS FOR SEPTEMBER 2022 SCHOOL PAN Marden Bridge Middle School Lovaine Avenue 150 Whitley Bay, NE25 8RW Monkseaton Middle School Vernon Drive 96 Monkseaton, NE25 8JN Valley Gardens Middle Valley Gardens 180 Whitley Bay, NE25 9AQ Wellfield Middle School Kielder Road, South Wellfield 60 Whitley Bay, NE25 9WQ Burnside College St Peters Road 208 School has a sixth form Wallsend, NE28 7LQ Churchill Community College Churchill Street 190 School has sixth form Wallsend, NE28 7TN George Stephenson High School Southgate 228 School has sixth form Killingworth, NE12 6SA John Spence Community College Preston North Road 177 North Shields, Ne29 9PU Longbenton High Halisham Avenue 180 School has sixth form Longenton, NE12 8ER Marden High School Hartington Road 181 North Shields, NE30 3RZ Monkseaton High School Seatonville Road 240 School has sixth form Whitley Bay, NE25 9EQ Norham High School Alnwick Avenue 90 North Shields, NE29 7BU Whitley Bay High School School has sixth form Deneholm 370 Whitley Bay, NE25 9AS In each school the Governing Body is the Admissions Authority and is responsible for determining the school’s admissions policy. The planned admission number (PAN) for each school is given in the table shown. Where the school receives more applications than places available the following admission criteria are used to decide on admission to Learning Trust Schools. All Learning Trust Schools operate an equal preference system for processing parental preferences. In accordance with the Education Act 1996, children with a Statement of Special Educational Needs are required to be admitted to the school named in the statement and with effect from September 2014 those children with an Education Health and Care Plan (EHCP). -

Rebecca-Ferguson.Pdf

Personal Information: Name Rebecca Main Subject Physical Second Subject English Ferguson Education My academic qualifications: School/College University John Spence Community High School (2004 - 2009) Sunderland University (2013 - 2014) GCSE: PE (A*), English (A), Maths (B), Additional Science (B), BSc (Hons): Sport and Exercise Development (First Class) Science (B), Geography (A*), Religious Studies (A*) BTEC Level 2: Art (Distinction), ICT (Distinction) Newcastle University (2016-2017) MSc: International Marketing (Merit) Kings Sixth Form (2009 - 2011) AS Level: PE (B), English Language and Literature (B) North East Partnership SCITT (2018-2019) A-Level: PE (B), English Language and Literature (B) PGCE and QTS: Secondary Physical Education (Pending) Tyne Metropolitan College (2011-2013) Foundation Degree: Science - Sports Coaching The experience I have had in schools: PGCE Placements Whitley Bay High School, North Tyneside (September - December 2018) Wellfield Middle School, North Tyneside (January - June 2019) Monkseaton High School, North Tyneside (January - June 2019) Undergraduate Placements John Spence High School, North Tyneside (January - February 2018) Kings Priory School, North Tyneside (April 2018, 40 hours) King Edwards Primary School, North Tyneside (September - March 2018) The strengths I have within my main subject area: Personal Strengths NGB/Other Coaching Awards Teaching Strengths • Golf achievements: • Teachers Trampolining Award Level • Broad subject knowledge in a wide 1 handicap, represented England at Turnberry in a 1 & 2 (2018) variety of sports, including athletics, National competition (2017), National Howdidido • STA Safety Award for Teachers tennis, volleyball, badminton, table Order of Merit winner in 2013 and 2017, Tynemouth & School Teachers Foundation tennis and netball Golf Club course record holder (6 under par), Certificate (2018) • Strong theoretical knowledge in Northern Golfer Champion of Champions (2017), 6 • Introductory CPD Award in both GCSE and A-Level PE. -

2015 52 Brandon and Byshottles Parish Council

BRANDON AND BYSHOTTLES PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS 6 GOATBECK TERRACE, LANGLEY MOOR, DURHAM ON FRIDAY 16TH JANUARY 2015 AT 6.30 PM PRESENT Councillor T Akins (in the Chair) and Councillors Bell, Mrs Bonner, Mrs Chaplow, Clegg, Mrs Gates, Graham, Grantham, Jamieson, Jones, Mrs Rodgers, Stoddart, Sims, Taylor, Turnbull and Mrs Wharton 153. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest received. 154. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION There were no questions from the public in the specified time. 155. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Mrs Akins, Nelson, Mrs Nelson and Rippin. RESOLVED: To receive the apologies. 156. MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 19 TH DECEMBER 2014 RESOLVED: To add Councillors Graham and Sims apologies, then approve the minutes as a true record. 157. MINUTES OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE HELD ON 7TH JANUARY 2015 RESOLVED: To approve the minutes as a true record and to set a precept of £149,760 for 2015/16. 158. ATTENDANCE OF MAYOR OF DURHAM TO SAY PERSONAL THANK YOU FOR DONATION TO HIS CHARITY The Mayor and Mayoress of Durham were in attendance and thanked the Chairman and Members for their kind donation to his charity which was presented to him at the switch on of the Christmas lights in Langley Moor. The Chairman thanked the Mayor and Mayoress for their attendance. 2015 52 159. PRESENTATION OF DONATIONS The Chairman presented donations to the following:- Brandon Carrside Youth & Community Project The Hive Holocaust Memorial Day Lourdes Fund St. Luke’s Church 160. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The 1841 south Durham election Rider, Clare Margaret How to cite: Rider, Clare Margaret (1982) The 1841 south Durham election, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7659/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE 1841 SOUTH DURHAM ELECTION CLARE MARGARET RIDER M.A. THESIS 1982 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 72. V:A'••}••* TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents i List of Illustrations, Maps and Tables iii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations V Abstract vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 - THE NORTH-EAST BACKGROUND 4 a) The Economic and Social Background 4 b) The Political. -

NRT Index Stations

Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) A Abbey Wood T052, T200, T201 Aber T130 Abercynon T130 Aberdare T130 Aberdeen T026, T051, T065, T229, T240 Aberdour T242 Aberdovey T076 Abererch T076 Abergavenny T131 Abergele & Pensarn T081 Aberystwyth T076 Accrington T041, T097 Achanalt T239 Achnasheen T239 Achnashellach T239 Acklington T048 Acle T015 Acocks Green T071 Acton Bridge T091 Acton Central T059 Acton Main Line T117 Adderley Park T068 Addiewell T224 Addlestone T149 Adisham T212 Adlington (cheshire) T084 Adlington (lancashire) T082 Adwick T029, T031 Aigburth T103 Ainsdale T103 Aintree T105 Airbles T225 Airdrie T226 Albany Park T200 Albrighton T074 Alderley Edge T082, T084 Aldermaston T116 Aldershot T149, T155 Aldrington T188 Alexandra Palace T024 Alexandra Parade T226 Alexandria T226 Alfreton T034, T049, T053 Allens West T044 Alloa T230 Alness T239 Alnmouth For Alnwick T026, T048, T051 Alresford (essex) T011 Alsager T050, T067 Althorne T006 Page 1 of 53 Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) Althorpe T029 A Altnabreac T239 Alton T155 Altrincham T088 Alvechurch T069 Ambergate T056 Amberley T186 Amersham T114 Ammanford T129 Ancaster T019 Anderston T225, T226 Andover T160 Anerley T177, T178 Angmering T186, T188 Annan T216 Anniesland T226, T232 Ansdell & Fairhaven T097 Apperley Bridge T036, T037 Appleby T042 Appledore (kent) T192 Appleford T116 Appley Bridge T082 Apsley T066 Arbroath T026, T051, T229 Ardgay T239 Ardlui T227 Ardrossan Harbour T221 Ardrossan South Beach T221 -

Education Act 1918

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Education Act 1918. (See end of Document for details) Education Act 1918 1918 CHAPTER 39 8 and 9 Geo 5 An Act to make further provision with respect to Education in England and Wales and for purposes connected therewith. [8th August 1918] 1–13 . F1 Textual Amendments F1 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 14 . F2 Textual Amendments F2 S. 14 repealed by Education Act 1973 (c. 16), Sch. 2 Pt. I 15–41 . F3 Textual Amendments F3 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 42 . F4 Textual Amendments F4 S. 42 repealed by Education Act 1944 (c. 31), s. 101(4)(b) and S.R. & O. 1945/255 (1945 I, p. 290) 2 Education Act 1918 (c. 39) Educational Trusts – Document Generated: 2021-03-27 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Education Act 1918. (See end of Document for details) 43, 44. F5 Textual Amendments F5 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c. 51), Sch. 7 EDUCATIONAL TRUSTS 45 . F6 Textual Amendments F6 S. 45 repealed by Charities Act 1960 (c. 58), Sch. 7 Pt. I 46 . F7 Textual Amendments F7 Ss. 1–13, 15–41, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, Schs. 1, 2 repealed by Education Act 1921 (c.