Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frankfurt Dersleri1

Diyalog 2020/ 2: 448-452 (Book Review) Edebiyat Kuramı İçin Vazgeçilmez Kaynak Metinler: Frankfurt Dersleri1 Davut Dağabakan , Ağrı Bir ulusun, bir milletin gelişmesinde fen bilimlerinin olduğu kadar sosyal bilimlerin de önemi büyüktür. Sosyal bilimlere değer vermeyen ülkelerin fen bilimlerinde de gelişim gösteremedikleri görülür. Bu bağlamda sivilize olmuş bir uygarlık, gelişmiş bir toplum düzeyi için edebiyata, felsefeye, sosyolojiye, psikoloji ve antropolojiye değer verilmelidir. Sosyal bilimlerin teorisine, kuramsal çalışmalara, kavram icadına ve anadilde kavram oluşturmaya da dikkat edilmelidir. Söz konusu olan edebiyatsa, sadece şiir yazmaya, edebi ürünler oluşturmaya değil de işin estetik boyutu sayılan poetikaya da değer verilmelidir. Alman edebiyatı Türk edebiyatına binaen edebiyatın ya da başka sosyal bilimlerin estetiğini ve poetikasını şekillendirme bakımından çok erken dönemlerde uyanışını gerçekleştirmiştir. Edebiyat kuramı bakımından durumu değerlendirecek olursak Barok döneminde yaşamış Martin Opitz’in „Das Buch von der Deutschen Poeterey“ adlı şiir kuramı ve poetik metni Türk poetikalarından, daha doğrusu sistematik poetikasından beş yüz sene daha önce yazılmıştır. Bu bilinçlenme, bir uygarlığın sadece edebi eserlerle ilgilenmesini değil de edebi eylemin estetiğini ve poetikasını sistematik bir şekilde gerçekleştirme ahlakını da sunar o millete. Bu da her tür sosyal bilimler alanında derinlikli düşünmeyi sağlar. Sadece edebiyatın bir alt dalı olan şiir kuramı alanında değil, örneğin mimarinin poetikasında ya da bir çayın, kahvenin, bir mekânın poetikasında eşyaya nüfuz ve olgulara derinlikli bakma kudreti de böylelikle bu tür eserlerle sağlanmış olur. Erken başlayan Alman poetikası eylemleri çağlar boyu sistematik poetikalarla devam etmiş son asırda Goethe Üniversitesi, Frankfurt’ta 1959 yılında edebiyata, edebiyatın sorunlarına ve gelişimine ilgi duyacak öğrencilere (öğrenciler indinde aslında herkese) bir imkân sunmak amacıyla Frankfurt Dersleri’ni başlatmıştır. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

An Exploration of Materiality in Josef Winkler‘s Narrative Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY William Christopher Burwick IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Leslie Morris [October 2015] © William Christopher Burwick 2015 Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Prof. Leslie Morris, for her continued support of my project and my studies, for providing valuable insights into Austrian literature with her attentive reading and remarks, and for encouraging me to pursue my ideas. Prof. Ruth-Ellen Joeres, Prof. Arlene Teraoka, Prof. Rembert Hueser, Prof. Anatoly Liberman, and Prof. Mary Joe Maynes have also been significantly influential on this project. Their advice, their courses, and their support before and during this project shaped the content of the following pages. Indeed, the entire Department of German, Scandinavian, and Dutch at the University of Minnesota deserve thanks for their faith in me, for the education they have provided, and for their support of my research. Prof. Brigitte Prutti of the University of Washington, Seattle, introduced me to the novels of Josef Winkler and Materiality Theory and helped me develop my writing with my Master‘s Thesis that served as background to this dissertation. Peter and Helga Karlhuber, Vienna, provided housing, invited me to opening of exhibits, and acquainted me with a number of writers and literary journalists. They also initiated me into the art of literary exhibits, especially the Handke Exhibit ―Die Arbeit des Zuschauers. Peter Handke und das Theater.‖ Through their hospitality and friendship, I gained valuable insight into Austrian culture. -

Jenseitserzählungen in Der Gegenwartsliteratur Gegenwartsliteratur

isabelle stauffer (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der stauffer stauffer (Hg.) (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der Gegenwartsliteratur Gegenwartsliteratur n der Literatur der Gegenwart erlebt das Jenseits ein Comeback: Jenseitsfahrten und Begegnungen mit Toten bilden einen erstaunlich häufig anzutreffenden Stoff der in der Gegenwartsliteratur Jenseitserzählungen neueren Erzählliteratur. Dabei stellt das Jenseits für die Literatur des 21. Jahrhunderts eine besondere Heraus- forderung dar: Es geht darum, etwas Nicht-Wirkliches, Nicht-Erforschbares in ein säkularisiertes Umfeld einzu- bringen und einen produktiven Umgang mit der bildmäch- tigen Erzähltradition zu finden, die von Texten der Antike über die Bibel bis zu Dantes Divina Commedia reicht. Gerade die transformativen und grenzauflösenden Elemen- te von Jenseitserzählungen erweisen sich für die postsä- kulare Gesellschaft als attraktiv. Der Band versammelt Beiträge zu Jenseitserzählungen von Harold Pinter, Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Michel Houellebecq, Herta Müller, Michael Köhlmeier, Urs Widmer und anderen mehr. Universitätsverlag winter isbn 978-3-8253-6909-5 Heidelberg beiträge zur neueren literaturgeschichte Band 387 isabelle stauffer (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der Gegenwartsliteratur Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Gedruckt mit freundlicher -

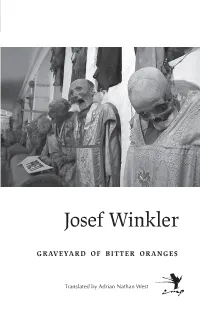

Graveyard of Bitter Oranges / Josef Winkler; Translated from First Contra Mundum Press the Original German by Adrian Edition 2015

“Graveyard of Bitter Oranges is a monstrous book, written with unequalled intensity.” Josef Winkler Josef .—Marcel Reich-Ranicki “Reading Winkler is like peering harder and harder into one of those painted Flemish hells that seethe with horribly inventive details of sin & retribution.” .—Alberto Manguel In 1979, Josef Winkler appeared on the literary horizon as if from nowhere, collecting numerous honors& the praise of the most promi- nent critical voices in Germany and Austria. Throughout the 1980s, he chronicled the malevolence, dissipation, and unregenerate Nazism en- Graveyard of Oranges Bitter demic to Austrian village life in an increasingly trenchant& hallucina- tory series of novels. At the decade’s end, fearing the silence that always lurks over the writer’s shoulder, he abandoned the Hell of Austria for Rome: not to flee, but to come closer to the darkness. There, he passes his days & nights among the junkies, rent boys, gypsies, & transsexuals who congregate around Stazione Termini and Piazza dei Cinquecento, as well as in the graveyards & churches, where his blasphemous reveries render the most hallowed rituals obscene. Traveling south to Naples& Palermo, he writes down his nightmares & recollections and all that he sees and reads, engaged, like Rimbaud, in a rational derangement of the senses, but one whose aim is a ruthless condemnation of church & state and the misery they sow in the lives of the downtrodden. Equal parts memoir, dream journal, and scandal sheet, the novel is, in the author’s words, a cage drawn around the horror. Writing here is an act of com- Josef Winkler memoration and redemption, a gathering of the bones of the forgotten dead and those outcast and spit on by society, their consecration in art, their final repatriation to the book’s titular graveyard. -

Geschichten Aus Der Geschichte Oesterreichs

Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorbemerkung 7 Österreich. Eine Biographie I Geboren am. Marianne Fritz Die Schwerkraft der Verhältnisse 14 MiloDor Wien, 12. April 1945 17 Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer Pius Enteignung, aber nicht durch Sozialismus 24 Ulrich Becher Kurz nach vier 36 Gerhard Fritsch Fasching 38 II Vater, Mutter, Angehörige. Ingeborg Bachmann Der Tod wird kommen (unvollendet) 43 Gerhard Amanshauser Daheim 52 Friederike Mayröcker Ironside oder öster¬ reichische Reise 56 Albert Paris Gütersloh Miniatur zur Schöpfung 58 Elfriede Jelinek Die Ausgesperrten 59 Elans Trümmer Luises Auffahrt 68 Hilde Spiel Die geselligen Eigenbrötler 79 Eleinz R. Unger David und Overkill 83 III Wohnhaft in. Peter Rosei Drau und Drava 89 Jutta Schütting Heimatland 96 Ernst Jandl War einst weg und bin jetzt hier 99 Hans Carl Artmann Keine Zeit für Twrdik-Rosen 104 Alois Brandstetter Die Fremdenangst oder Feinsein, beinander bleiben 106 IV Kindheit, Schule, Liebe. Alfred Paul Schmidt Auch früher ging das Leben weiter 115 5 Josef Winkler Der Ackermann aus Kärnten 120 Norbert C. Kaser erstkommunion oder die gewaltsame begegnung mit gott 123 Thomas Bernhard Die Ursache 129 Barbara Frischmuth Die Klosterschule 134 Werner Kofler Aus der Wildnis 139 Brigitte Schwaiger Wie kommt das Salz ins Meer 144 Max Maetz Einmal auf der Frankfurter Buchmesse sein 149 Konrad Bayer Briefe an Ida 156 V Lehrzeit, Beruf, Karriere. Franz Innerhofer Schattseite 162 Gernot Wolfgruber Herrenjahre 175 Reinhard P. Gruber Mein Wohlbefinden 184 Gerhard Roth Kreisky und Emil Jannings 191 Josef Haslinger Grubers mittlere Jahre 196 Gustav Ernst Brief der Haushälterin an die Herrschaft 221 Peter Marglnter Freie Wildbahn 228 VI Erbschäden, Kinderkrankheiten, chronische Leiden. -

Contemporary German Literature Collection) Hannelore M

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary The aM x Kade Center for Contemporary German German Literature Collection Literature Spring 1997 Thirteenth Annual Bibliography, 1997 (Contemporary German Literature Collection) Hannelore M. Lützeler Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/maxkade_biblio Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Lützeler, Hannelore M., "Thirteenth Annual Bibliography, 1997 (Contemporary German Literature Collection)" (1997). Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary German Literature Collection. 3. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/maxkade_biblio/3 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM x Kade Center for Contemporary German Literature at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary German Literature Collection by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Center for Contemporary German Literature Zentrum für deutschsprachige Gegenwartsliteratur Washington University One Brookings Drive Campus Box 1104 St. Louis, Missouri 63130-4899 Director: Paul Michael Lützeler Fourteenth Bibliography Spring 1998 Editor: Hannelore M. Spence I. AUTHORS Achilla Presse, Hamburg/Germany -Probsthayn, Lou A.: Dumm gelaufen. Kriminalroman (1996) Adonia-Verlag, Thalwil/Switzerland -Kobel, Ruth Elisabeth: Schichten. Gedichte (1991) -Kobel, Ruth Elisabeth: Wegzeichen. Gedichte (1987) A1 Verlag, München/Germany -Herburger, Günter: Das Glück. Eine Reise in Nähe und Ferne. (1994) -Herburger, Günter: Die Liebe. Eine Reise durch Wohl und Wehe. (1996) -Krusche, Dietrich: Stimmen im Rücken. Roman (1994) -Münscher, Alice: Ein exquisiter Leichnam. -

Welcome Package

WELCOME PACKAGE 2012-06-30 Carinthian International Club · A-9020 Klagenfurt, Dr. Franz-Palla-Gasse 21 P: +43 (0) 650 260 81 95 · [email protected] · www.cic-network.at Dear You! It´s a pleasure to welcome you to Carinthia. The CIC - Carinthian International Club has been created to offer useful information to expatriates and to make contact possible and strengthen links between people interested in benefiting from an international and multi- cultural experience. Advisory service enables people to take informed decisions in relation to work, living or the schooling of children in their new environment. Regular events and activities offer a platform for social networking and information exchange. Some of the benefits you can enjoy as a member of the CIC are: − CIC contact hours Come along and get help with settling in in Carinthia, appointments on demand. Please send an e-mail to [email protected] − CIC guidance and support service (e.g. work opportunities for family members and advice on schools). Meetings by appointment. − CIC get togethers – these are events for you to come along to. They offer opportunities to make contact with other expatriates and locals. − CIC summerkids – a childcare scheme (age 5 to 14) offered in August − CIC networking sessions - monthly meetings to chat and get to know each other, held in the evenings. − CIC language swap: One to one language coaching. − Opportunities to get involved and have your say e.g. translations, writing articles for the website, ideas. Carinthian International Club · A-9020 Klagenfurt, Dr. Franz-Palla-Gasse 21 P: +43 (0) 650 260 81 95 · [email protected] · www.cic-network.at − A diverse programme of activities - regular opportunities to take part in (e.g. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis AICHINGER Richard Reichensperger: Ilse

Inhaltsverzeichnis AICHINGER Richard Reichensperger: Ilse Aichingers frühe Dekonstruktionen n Klaus Kastberger: Überleben. Ein Kinderspiel — Ilse Aichinger: Die größere Hoffnung (1948) 18 BACHMANN - WANDER - INNERHOFER - GÜTERSLOH Hans Höller: Orpheus nach 1945. Zu Ingeborg Bachmann: Die gestundete Zeit (1953) 25 Gespräch mit Robert Schindel und Hans Höller 35 Klemens Renoldner: Erzählen gegen die Verzweiflung. Fred Wander: Der siebente Brunnen (1971) 39 Josef Winkler: Statement zu Franz Innerhofer: Schöne Tage (1974) 46 Klaus Kastberger: Franz Innerhofer: Schöne Tage 47 Bodo Hell: Notizen zu Albert Paris Gütersloh: Sonne und Mond (1962) 55 Michael Hansel: „Der Teufel hole die Bücher, die einer versteht!" Albert Paris Gütersloh: Sonne und Mond 61 BAYER - HINTERBERGER - JELINEK - CELAN Franz Schuh: Kommentar zu einer Lesung aus Konrad Bayer: der sechste sinn (1966) 71 Oliver Jahraus: Konrad Bayer: der sechste sinn, roman 77 Erich Demmer: Anmerkungen zu Ernst Hinterberger: Kleine Leute (1989) 84 Johann Sonnleitner: Ernst Hinterberger: Kleine Leute. Roman einer Zeit und einer Familie 86 Gespräch mit Ernst Hinterberger und Erich Demmer 95 Ria Endres: Keine Lust für niemanden. Elfriede Jelinek: Lust (1989) 98 Matthias Luserke-Jaqui: Trivialmythos Lust und Liebe? Über Elfriede Jelinek: Lust 102 Axel Gellhaus: „Im Glockenstuhl deines Schweigens." Paul Celan: Mohn und Gedächtnis (1952) 109 Gespräch mit Robert Schindel und Axel Gellhaus 119 PRIESSNITZ - KERSCHBAUMER - DODERER - HANDKE Ulf Stolterfoht: Kommentar zu einer Lesung aus Reinhard Priessnitz: vierundvierzig gedickte (1978) 125 Thomas Eder: Auf der Bühne des Verstehens. Zu Reinhard Priessnitz: vierundvierzig gedickte 129 Konrad Paul Liessmann: Die Kraft der Vergegenwärtigung. Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer: Der weibliche Name des Widerstands (1980) 136 Gespräch mit Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer und Konrad Paul Liessmann .. -

Littérature D'autriche

revue littéraire mensuelle LITTÉRATURE D’AUTRICHE Pina Bausch Agha Shahid Ali juin-juillet 2001 Antonio José Ponte L’Autriche est entrée dans le XXIe siècle avec fracas. Elle traverse aujourd’hui une crise politique sans précédent depuis l’après-guerre, tant au plan national qu’international. Consensuel et neutre, ce pays qui se croyait à l’abri de l’Histoire s’est senti rattrapé de tous côtés par celle-ci au cours des années quatre-vingt-dix. Les murs se sont effondrés, et pas seulement à Berlin. Le passé refoulé (celui d’une période nazie trop facilement qualifiée d’« occupation » par la rhétorique officielle) est revenu comme un boomerang, tandis que l’avenir, avec la fin du bloc soviétique et l’apparition des processus économiques de la mondialisation, s’ouvrait sur des gouffres de perplexité. Les intellectuels et les écrivains étaient-ils préparés à traverser une telle « crise des fondements », pour reprendre une expression chère à Robert Musil ? L’avaient-ils pressentie, diagnostiquée, voire provoquée comme on a pu le reprocher à certains d’entre eux ? L’un des paradoxes qui traversent l’Autriche au tournant du XXIe siècle n’est-il pas, sur fond de grave crise morale et politique, l’extrême vitalité de la création littéraire et artistique qui s’y déploie ? ÉTUDES ET TEXTES DE Jacques Lajarrige, Christine Lecerf, Jean-Yves Masson, Gert Jonke, Elfriede Jelinek, Antonio Fian, Franz Haas, Gerald Stieg, Wolfgang Sabler, Klaus Zeyringer, Bernard Banoun, Déborah Gonzales-Vangell, Ilse Aichinger, Hans Carl Artmann, Heimrad Bäcker, Werner Kofler, Éric Dortu, Josef Winkler, Robert Menasse, Ernst Jandl, Alfred Kolleritsch, Robert Schindel, Lilian Faschinger, Gerhard Ruiss, Evelyn Schlag, Franz Josef Czernin, Ferdinand Schmatz, Alexandra Fukari. -

Forum: Austrian Studies the Focus of This Issue of the the German Quarterly Is on Austrian Studies

Forum: Austrian Studies the focus of this issue of the The German Quarterly is on austrian studies. the five preceding essays, each illustrating different approaches to the study of aus- tria’s literatures and cultures, were not solicited specifically for this issue, but were submitted through the regular channels and underwent a double-blind peer re- view process. in order to gain more insight into scholarly developments in the field, however, we decided to also create space in this issue for a more deliberate reflection on what it means to do austrian studies. the editors of this forum asked a number of scholars (most of them working in the Us, but also one rep- resentative from the Uk and one from austria) for their views on the state of austrian studies today. We were interested specifically in developments in schol- arship on austrian literature and culture since the year 2000. We asked our con- tributors to illustrate what they see as important accomplishments, the challenges and dilemmas they perceive as specific to austrian studies, problems and issues that remain underexamined, and promising trends and developments. Below you will find the results. the development of the field of austrian stud- ies certainly has been driven by institutional structures: organizations, journals, and curricula. But scholarship also developed its own dynamics that often re- mained implicit. research in literary and cultural studies clearly moves in certain directions without an explicit master plan (and maybe this is not such a bad thing). the following short essays attempt to trace those dynamics. Most of the contributions reveal a concern about canonization and a narrowing of the field. -

Katecwscheblætteï □□ □□

Zeitschrift für Religionsuntemcht, GenJeindeJ^techese, Kirchliche Jugendarbeit . 2 /]f KatecWscheBlætteï □□ □□ Wörterleuchten ■ Das Ringen mit der Sprache Religiöses Lernen in der Gegenwartsliteratur Über religiöse Themen ins Gespräch kommen W ö rte rle u c h te n | REFLEXION Von guten Texten wunderbar geborgen? Text: Georg Langenhorst Unbemerkt von Theologie und Religionspädagogik sprechen Kultur wissenschaftler aktuell von einem religious turn. Gerade in der Gegenwartsliteratur finden sich herausfordernde Neuaufbrüche der Gottessuche. Religiöses Lernen lässt sich mit vielen dieser Texte anregend gestalten. Gott in der Literatur unserer Zeit? Lange Zeit man sich dieses Wort verbietet, hat man extreme schien festzustehen, dass die hinter dieser Frage Schwierigkeiten, bestimmte Dinge zu sagen.« aufscheinende Suche nur ein Ergebnis finden Gegen alle falschen Vereinnahmungen betont könne: »Gott liebt es, sich zu verstecken« {Ku er: »Es darf nicht sein, dass wir das Wort Gott schel 2007). Der Blick in die Gegenwartsliteratur nur verwenden, um uns gegenseitig zu versi könnte dann nur eine weitere Bestätigung der chern, dass wir alle schon irgendwie gut und resignativen Einsicht erbringen: Der Gottesge richtig seien. [...] Wenn ich von Gott spreche, danke befindet sich in der Gegenwartskultur in weiß jeder, dass etwas gemeint ist, das außerhalb einem unaufhaltsamen Prozess des Verschwin von uns liegt.« {Maier 2005) Von Gott ist denn dens. auch in Maiers Romanwerk immer wieder die Rede. Seit 2010 arbeitet er an einem mehrteili Neue Annäherungen an Gott gen erzählerischen Großprojekt unter dem Ar beitstitel »Ortsumgehung«, das sich vom Zim So könnte der Befund sein - ist er aber nicht. mer zum Haus, zur Straße, zum Dorf, zum Land Ein genauer Blick vor allem in die Entwicklun seiner Kindheit immer mehr weiten soll bis hin gen der letzten 20 Jahre (vgl. -

Die Entsetzungen Des Josef Winkler

alexandra Millner und Christine Ivanovic (hg.) Die Entsetzungen des Josef Winkler Mit frühen Gedichten des autors sowie einer Bibliografie zu Josef Winkler 1998 – 2013 sonderzahl Die Abbildungen aus Josef Winklers indischem Notizbuch „Pune (India), August 2012“ wurden vom Autor mit freundlicher Genehmigung zur Ver- fügung gestellt. www.sonderzahl.at Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2014 Sonderzahl Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H., Wien Schrift: Minion Pro Druck: CPI buchbücher.de gmbh, Birkach ISBN 978 3 85449 415 7 Umschlag von Thomas Kussin unter Verwendung einer Fotografie von Christine Schwichtenberg Inhalt Alexandra Millner, Christine Ivanovic Die Entsetzungen des Josef Winkler. Zur Einführung ……… 15 Leben – Mythos – Literatur Klaus Amann Attacke und Rettung. Zu einem Grundmuster bei Josef Winkler ………………… 26 Franz Haas Josef Winklers Rom und seine entsetzlich lebendigen Bilder in Natura morta ………………………… 46 Evelyne Polt-Heinzl Josef Winkler: Verschleppte Kindheiten – Verfehlte Beheimatung oder Die Folgen von Literatur ……………… 58 Christine Ivanovic Vom Frauenraub zur Heimkehr des verlorenen Sohnes. Josef Winklers Die Verschleppung in der Tradition mythischer Entsetzung ……………………………………… 72 Tod – Bild – Dichtung Dana Pfeiferová Zwischen Angst und Beschwörung: Josef Winklers Todesbilder ……………………………… 104 Hiroshi Yamamoto Vermessung von Todeslandschaften. Zum Irre- und Engführungsverfahren in Josef Winklers Roppongi ………………………………… 120 Daniel Lange, Stefan Lessmann Josef Winkler aus der Vogelperspektive. Volatile Formationen im Zeichen der Postmoderne………