Forum: Austrian Studies the Focus of This Issue of the the German Quarterly Is on Austrian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frankfurt Dersleri1

Diyalog 2020/ 2: 448-452 (Book Review) Edebiyat Kuramı İçin Vazgeçilmez Kaynak Metinler: Frankfurt Dersleri1 Davut Dağabakan , Ağrı Bir ulusun, bir milletin gelişmesinde fen bilimlerinin olduğu kadar sosyal bilimlerin de önemi büyüktür. Sosyal bilimlere değer vermeyen ülkelerin fen bilimlerinde de gelişim gösteremedikleri görülür. Bu bağlamda sivilize olmuş bir uygarlık, gelişmiş bir toplum düzeyi için edebiyata, felsefeye, sosyolojiye, psikoloji ve antropolojiye değer verilmelidir. Sosyal bilimlerin teorisine, kuramsal çalışmalara, kavram icadına ve anadilde kavram oluşturmaya da dikkat edilmelidir. Söz konusu olan edebiyatsa, sadece şiir yazmaya, edebi ürünler oluşturmaya değil de işin estetik boyutu sayılan poetikaya da değer verilmelidir. Alman edebiyatı Türk edebiyatına binaen edebiyatın ya da başka sosyal bilimlerin estetiğini ve poetikasını şekillendirme bakımından çok erken dönemlerde uyanışını gerçekleştirmiştir. Edebiyat kuramı bakımından durumu değerlendirecek olursak Barok döneminde yaşamış Martin Opitz’in „Das Buch von der Deutschen Poeterey“ adlı şiir kuramı ve poetik metni Türk poetikalarından, daha doğrusu sistematik poetikasından beş yüz sene daha önce yazılmıştır. Bu bilinçlenme, bir uygarlığın sadece edebi eserlerle ilgilenmesini değil de edebi eylemin estetiğini ve poetikasını sistematik bir şekilde gerçekleştirme ahlakını da sunar o millete. Bu da her tür sosyal bilimler alanında derinlikli düşünmeyi sağlar. Sadece edebiyatın bir alt dalı olan şiir kuramı alanında değil, örneğin mimarinin poetikasında ya da bir çayın, kahvenin, bir mekânın poetikasında eşyaya nüfuz ve olgulara derinlikli bakma kudreti de böylelikle bu tür eserlerle sağlanmış olur. Erken başlayan Alman poetikası eylemleri çağlar boyu sistematik poetikalarla devam etmiş son asırda Goethe Üniversitesi, Frankfurt’ta 1959 yılında edebiyata, edebiyatın sorunlarına ve gelişimine ilgi duyacak öğrencilere (öğrenciler indinde aslında herkese) bir imkân sunmak amacıyla Frankfurt Dersleri’ni başlatmıştır. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

An Exploration of Materiality in Josef Winkler‘s Narrative Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY William Christopher Burwick IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Leslie Morris [October 2015] © William Christopher Burwick 2015 Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Prof. Leslie Morris, for her continued support of my project and my studies, for providing valuable insights into Austrian literature with her attentive reading and remarks, and for encouraging me to pursue my ideas. Prof. Ruth-Ellen Joeres, Prof. Arlene Teraoka, Prof. Rembert Hueser, Prof. Anatoly Liberman, and Prof. Mary Joe Maynes have also been significantly influential on this project. Their advice, their courses, and their support before and during this project shaped the content of the following pages. Indeed, the entire Department of German, Scandinavian, and Dutch at the University of Minnesota deserve thanks for their faith in me, for the education they have provided, and for their support of my research. Prof. Brigitte Prutti of the University of Washington, Seattle, introduced me to the novels of Josef Winkler and Materiality Theory and helped me develop my writing with my Master‘s Thesis that served as background to this dissertation. Peter and Helga Karlhuber, Vienna, provided housing, invited me to opening of exhibits, and acquainted me with a number of writers and literary journalists. They also initiated me into the art of literary exhibits, especially the Handke Exhibit ―Die Arbeit des Zuschauers. Peter Handke und das Theater.‖ Through their hospitality and friendship, I gained valuable insight into Austrian culture. -

Jenseitserzählungen in Der Gegenwartsliteratur Gegenwartsliteratur

isabelle stauffer (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der stauffer stauffer (Hg.) (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der Gegenwartsliteratur Gegenwartsliteratur n der Literatur der Gegenwart erlebt das Jenseits ein Comeback: Jenseitsfahrten und Begegnungen mit Toten bilden einen erstaunlich häufig anzutreffenden Stoff der in der Gegenwartsliteratur Jenseitserzählungen neueren Erzählliteratur. Dabei stellt das Jenseits für die Literatur des 21. Jahrhunderts eine besondere Heraus- forderung dar: Es geht darum, etwas Nicht-Wirkliches, Nicht-Erforschbares in ein säkularisiertes Umfeld einzu- bringen und einen produktiven Umgang mit der bildmäch- tigen Erzähltradition zu finden, die von Texten der Antike über die Bibel bis zu Dantes Divina Commedia reicht. Gerade die transformativen und grenzauflösenden Elemen- te von Jenseitserzählungen erweisen sich für die postsä- kulare Gesellschaft als attraktiv. Der Band versammelt Beiträge zu Jenseitserzählungen von Harold Pinter, Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Michel Houellebecq, Herta Müller, Michael Köhlmeier, Urs Widmer und anderen mehr. Universitätsverlag winter isbn 978-3-8253-6909-5 Heidelberg beiträge zur neueren literaturgeschichte Band 387 isabelle stauffer (Hg.) Jenseitserzählungen in der Gegenwartsliteratur Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Gedruckt mit freundlicher -

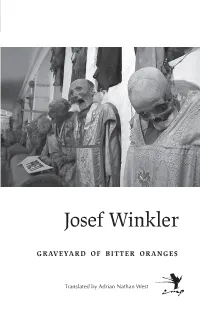

Graveyard of Bitter Oranges / Josef Winkler; Translated from First Contra Mundum Press the Original German by Adrian Edition 2015

“Graveyard of Bitter Oranges is a monstrous book, written with unequalled intensity.” Josef Winkler Josef .—Marcel Reich-Ranicki “Reading Winkler is like peering harder and harder into one of those painted Flemish hells that seethe with horribly inventive details of sin & retribution.” .—Alberto Manguel In 1979, Josef Winkler appeared on the literary horizon as if from nowhere, collecting numerous honors& the praise of the most promi- nent critical voices in Germany and Austria. Throughout the 1980s, he chronicled the malevolence, dissipation, and unregenerate Nazism en- Graveyard of Oranges Bitter demic to Austrian village life in an increasingly trenchant& hallucina- tory series of novels. At the decade’s end, fearing the silence that always lurks over the writer’s shoulder, he abandoned the Hell of Austria for Rome: not to flee, but to come closer to the darkness. There, he passes his days & nights among the junkies, rent boys, gypsies, & transsexuals who congregate around Stazione Termini and Piazza dei Cinquecento, as well as in the graveyards & churches, where his blasphemous reveries render the most hallowed rituals obscene. Traveling south to Naples& Palermo, he writes down his nightmares & recollections and all that he sees and reads, engaged, like Rimbaud, in a rational derangement of the senses, but one whose aim is a ruthless condemnation of church & state and the misery they sow in the lives of the downtrodden. Equal parts memoir, dream journal, and scandal sheet, the novel is, in the author’s words, a cage drawn around the horror. Writing here is an act of com- Josef Winkler memoration and redemption, a gathering of the bones of the forgotten dead and those outcast and spit on by society, their consecration in art, their final repatriation to the book’s titular graveyard. -

Geschichten Aus Der Geschichte Oesterreichs

Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorbemerkung 7 Österreich. Eine Biographie I Geboren am. Marianne Fritz Die Schwerkraft der Verhältnisse 14 MiloDor Wien, 12. April 1945 17 Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer Pius Enteignung, aber nicht durch Sozialismus 24 Ulrich Becher Kurz nach vier 36 Gerhard Fritsch Fasching 38 II Vater, Mutter, Angehörige. Ingeborg Bachmann Der Tod wird kommen (unvollendet) 43 Gerhard Amanshauser Daheim 52 Friederike Mayröcker Ironside oder öster¬ reichische Reise 56 Albert Paris Gütersloh Miniatur zur Schöpfung 58 Elfriede Jelinek Die Ausgesperrten 59 Elans Trümmer Luises Auffahrt 68 Hilde Spiel Die geselligen Eigenbrötler 79 Eleinz R. Unger David und Overkill 83 III Wohnhaft in. Peter Rosei Drau und Drava 89 Jutta Schütting Heimatland 96 Ernst Jandl War einst weg und bin jetzt hier 99 Hans Carl Artmann Keine Zeit für Twrdik-Rosen 104 Alois Brandstetter Die Fremdenangst oder Feinsein, beinander bleiben 106 IV Kindheit, Schule, Liebe. Alfred Paul Schmidt Auch früher ging das Leben weiter 115 5 Josef Winkler Der Ackermann aus Kärnten 120 Norbert C. Kaser erstkommunion oder die gewaltsame begegnung mit gott 123 Thomas Bernhard Die Ursache 129 Barbara Frischmuth Die Klosterschule 134 Werner Kofler Aus der Wildnis 139 Brigitte Schwaiger Wie kommt das Salz ins Meer 144 Max Maetz Einmal auf der Frankfurter Buchmesse sein 149 Konrad Bayer Briefe an Ida 156 V Lehrzeit, Beruf, Karriere. Franz Innerhofer Schattseite 162 Gernot Wolfgruber Herrenjahre 175 Reinhard P. Gruber Mein Wohlbefinden 184 Gerhard Roth Kreisky und Emil Jannings 191 Josef Haslinger Grubers mittlere Jahre 196 Gustav Ernst Brief der Haushälterin an die Herrschaft 221 Peter Marglnter Freie Wildbahn 228 VI Erbschäden, Kinderkrankheiten, chronische Leiden. -

Kunst- Und Kulturbericht 2015

Kunst- und Kultur- bericht 2015 Impressum Medieninhaber, Verleger und Herausgeber: Bundeskanzleramt, Sektion für Kunst und Kultur, Concordiaplatz 2, 1010 Wien Konzept, Redaktion, Lektorat: Sonja Bognar, Robert Stocker, Charlotte Sucher Mitarbeit Lektorat: Herbert Hofreither Gestaltung: BKA Design & Grafik – Florin Buttinger, Melanie Doblinger Druck: RemaPrint Die Redaktion dankt allen Beiträgern für die gute Zusammenarbeit. Kunst- und Kulturbericht 2015 Wien, 2016 Vorwort Zeitschriften 229 Bundesminister Mag. Thomas Drozda 5 Musik 233 Sektionschefin Mag. Andrea Ecker 8 Wiener Hofmusikkapelle 241 Bundestheater 245 Kunst- und Kulturförderung 11 Bundestheater-Holding 247 Rechtliche Grundlagen 13 Burgtheater 253 Kunst- und Kulturausgaben, Wiener Staatsoper 261 Genderpolitik 21 Volksoper Wien 271 Wiener Staatsballett 279 Institutionen ART for ART Theaterservice 285 und Förderungs programme 37 Darstellende Kunst 291 Bundesmuseen 39 Bildende Kunst, Architektur, Albertina 47 Design, Mode, Fotografie 299 Österreichische Galerie Belvedere 59 Film, Kino, Video- und Medienkunst 307 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien 73 Kulturinitiativen 315 Österreichisches Theatermuseum 81 Europäische und internationale Weltmuseum Wien 85 Kulturpolitik 323 MAK – Österreichisches Museum für Festspiele, Großveranstaltungen 339 angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst 91 Soziales 349 Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien – mumok 101 Ausgaben im Detail 353 Naturhistorisches Museum Wien 109 Museen, Archive, Wissenschaft 355 Technisches Museum Wien 123 Baukulturelles Erbe, -

Victimhood Through a Creaturely Lens: Creatureliness, Trauma and Victimhood in Austrian and Italian Literature After 1945

Victimhood through a Creaturely Lens: Creatureliness, Trauma and Victimhood in Austrian and Italian Literature after 1945. Alexandra Julie Hills University College London PhD Thesis ‘ I, ALEXANDRA HILLS confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis.' 1 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for their continual support of my research thanks to a Research Preparation Award in 2009 and a Collaborative Doctoral Award in the context of the “Reverberations of War” project under the direction of Prof Mary Fulbrook and Dr Stephanie Bird. I also wish to thank the UCL Graduate School for funding two research trips to Vienna and Florence where I conducted archival and institutional research, providing essential material for the body of the thesis. I would like to acknowledge the libraries and archives which hosted me and aided me in my research: particularly, the Literaturarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Dr. Volker Kaukoreit at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek who facilitated access to manuscript material, the Wienbibliothek, the Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi in Turin and Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale. For their constant patience, resourcefulness and assistance, I wish to express my gratitude to staff at UCL and the British libraries, without whom my research would not have been possible. My utmost thanks go to my supervisors, Dr Stephanie Bird and Dr Florian Mussgnug, for their encouragement and enthusiasm throughout my research. Their untiring support helped me develop as a thinker; their helpful responses made me improve as a writer, and I am extremely grateful for their patience. -

Jüdische Literatur in Österreich Nach Waldheim

nap Andrea Reiter new academic press Dieses Buch befasst sich mit dem literarischen und filmischen Werk jüdischer Autoren und Autorinnen im Österreich der letzten dreißig Jahre. Die sogenannte Waldheim-Affäre von 1986 steht für einen Paradigmenwechsel im Umgang mit Krieg und Shoah in Österreich. Jüdische Literatur Gezeigt wird dies einerseits an den unterschiedlichen Reaktionen auf die Waldheim-Affäre in den Autobiografien der in Österreich Kriegsgeneration (Bruno Kreisky u.a.) und Ruth Beckermanns. Das neue jüdische Selbstverständnis der jüngeren Generation andererseits erschließt sich aus verschiedenen kulturellen nach Waldheim Räumen, die sowohl geografisch lokalisierbar sind (etwa die neue jüdische Infrastruktur z. B. in der Leopoldstadt) als auch in der Veranstaltungskultur erkennbar werden. Eingehend widmet sich dieses Buch dem jüdischen Selbstverständnis, wie es sich in den (auto)biografisch gefärbten Andrea Reiter studierte Germanistik nach Waldheim Romanen und Filmen der jüngeren jüdischen Autorinnen und in Salzburg, sie ist Mitglied der „Gesell- Autoren offenbart. Den Analysen liegt ein kulturelles schaft für Exilforschung“ und derzeit Verständnis des Jüdischen zugrunde, das sich jenseits von Religion und Abstammung an der Selbstverortung der Autoren Professorin für „German in Modern und Autorinnen orientiert. Erklärtes Ziel dieses Buches ist es, in Österreich Literatur Jüdische Languages and Linguistics” an der zu zeigen, dass die jüdische Kultur eines mitteleuropäischen University of Southampton, Kernlandes an der Jahrtausendwende eben nicht nur von Nicht- Großbritannien. Juden aufrechterhalten wird (wie etwa Ruht Ellen Gruber dies behauptete), sondern sich als vielfältige autochthon jüdische Identität zeigt. Andrea Reiter ISBN 978-3-7003-2067-8 www.newacademicpress.at nap new academic press Andrea Reiter Jüdische Literatur in Österreich nach Waldheim Bildnachweis: S. -

Contemporary German Literature Collection) Hannelore M

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary The aM x Kade Center for Contemporary German German Literature Collection Literature Spring 1997 Thirteenth Annual Bibliography, 1997 (Contemporary German Literature Collection) Hannelore M. Lützeler Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/maxkade_biblio Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Lützeler, Hannelore M., "Thirteenth Annual Bibliography, 1997 (Contemporary German Literature Collection)" (1997). Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary German Literature Collection. 3. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/maxkade_biblio/3 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM x Kade Center for Contemporary German Literature at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Bibliography of the Special Contemporary German Literature Collection by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Center for Contemporary German Literature Zentrum für deutschsprachige Gegenwartsliteratur Washington University One Brookings Drive Campus Box 1104 St. Louis, Missouri 63130-4899 Director: Paul Michael Lützeler Fourteenth Bibliography Spring 1998 Editor: Hannelore M. Spence I. AUTHORS Achilla Presse, Hamburg/Germany -Probsthayn, Lou A.: Dumm gelaufen. Kriminalroman (1996) Adonia-Verlag, Thalwil/Switzerland -Kobel, Ruth Elisabeth: Schichten. Gedichte (1991) -Kobel, Ruth Elisabeth: Wegzeichen. Gedichte (1987) A1 Verlag, München/Germany -Herburger, Günter: Das Glück. Eine Reise in Nähe und Ferne. (1994) -Herburger, Günter: Die Liebe. Eine Reise durch Wohl und Wehe. (1996) -Krusche, Dietrich: Stimmen im Rücken. Roman (1994) -Münscher, Alice: Ein exquisiter Leichnam. -

Welcome Package

WELCOME PACKAGE 2012-06-30 Carinthian International Club · A-9020 Klagenfurt, Dr. Franz-Palla-Gasse 21 P: +43 (0) 650 260 81 95 · [email protected] · www.cic-network.at Dear You! It´s a pleasure to welcome you to Carinthia. The CIC - Carinthian International Club has been created to offer useful information to expatriates and to make contact possible and strengthen links between people interested in benefiting from an international and multi- cultural experience. Advisory service enables people to take informed decisions in relation to work, living or the schooling of children in their new environment. Regular events and activities offer a platform for social networking and information exchange. Some of the benefits you can enjoy as a member of the CIC are: − CIC contact hours Come along and get help with settling in in Carinthia, appointments on demand. Please send an e-mail to [email protected] − CIC guidance and support service (e.g. work opportunities for family members and advice on schools). Meetings by appointment. − CIC get togethers – these are events for you to come along to. They offer opportunities to make contact with other expatriates and locals. − CIC summerkids – a childcare scheme (age 5 to 14) offered in August − CIC networking sessions - monthly meetings to chat and get to know each other, held in the evenings. − CIC language swap: One to one language coaching. − Opportunities to get involved and have your say e.g. translations, writing articles for the website, ideas. Carinthian International Club · A-9020 Klagenfurt, Dr. Franz-Palla-Gasse 21 P: +43 (0) 650 260 81 95 · [email protected] · www.cic-network.at − A diverse programme of activities - regular opportunities to take part in (e.g. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis AICHINGER Richard Reichensperger: Ilse

Inhaltsverzeichnis AICHINGER Richard Reichensperger: Ilse Aichingers frühe Dekonstruktionen n Klaus Kastberger: Überleben. Ein Kinderspiel — Ilse Aichinger: Die größere Hoffnung (1948) 18 BACHMANN - WANDER - INNERHOFER - GÜTERSLOH Hans Höller: Orpheus nach 1945. Zu Ingeborg Bachmann: Die gestundete Zeit (1953) 25 Gespräch mit Robert Schindel und Hans Höller 35 Klemens Renoldner: Erzählen gegen die Verzweiflung. Fred Wander: Der siebente Brunnen (1971) 39 Josef Winkler: Statement zu Franz Innerhofer: Schöne Tage (1974) 46 Klaus Kastberger: Franz Innerhofer: Schöne Tage 47 Bodo Hell: Notizen zu Albert Paris Gütersloh: Sonne und Mond (1962) 55 Michael Hansel: „Der Teufel hole die Bücher, die einer versteht!" Albert Paris Gütersloh: Sonne und Mond 61 BAYER - HINTERBERGER - JELINEK - CELAN Franz Schuh: Kommentar zu einer Lesung aus Konrad Bayer: der sechste sinn (1966) 71 Oliver Jahraus: Konrad Bayer: der sechste sinn, roman 77 Erich Demmer: Anmerkungen zu Ernst Hinterberger: Kleine Leute (1989) 84 Johann Sonnleitner: Ernst Hinterberger: Kleine Leute. Roman einer Zeit und einer Familie 86 Gespräch mit Ernst Hinterberger und Erich Demmer 95 Ria Endres: Keine Lust für niemanden. Elfriede Jelinek: Lust (1989) 98 Matthias Luserke-Jaqui: Trivialmythos Lust und Liebe? Über Elfriede Jelinek: Lust 102 Axel Gellhaus: „Im Glockenstuhl deines Schweigens." Paul Celan: Mohn und Gedächtnis (1952) 109 Gespräch mit Robert Schindel und Axel Gellhaus 119 PRIESSNITZ - KERSCHBAUMER - DODERER - HANDKE Ulf Stolterfoht: Kommentar zu einer Lesung aus Reinhard Priessnitz: vierundvierzig gedickte (1978) 125 Thomas Eder: Auf der Bühne des Verstehens. Zu Reinhard Priessnitz: vierundvierzig gedickte 129 Konrad Paul Liessmann: Die Kraft der Vergegenwärtigung. Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer: Der weibliche Name des Widerstands (1980) 136 Gespräch mit Marie-Thérèse Kerschbaumer und Konrad Paul Liessmann .. -

The Austrian Imaginary of Wilderness: Landscape, History and Identity In

The Austrian Imaginary of Wilderness: Landscape, History and Identity in Contemporary Austrian Literature Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Magro Algarotti, M.A. Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures. The Ohio State University 2012 Committee: Gregor Hens, Advisor Bernd Fischer Bernhard Malkmus Copyright by Jennifer Magro Algarotti 2012 Abstract Contemporary Austrian authors, such as Christoph Ransmayr, Elfriede Jelinek, Raoul Schrott, and Robert Menasse, have incorporated wilderness as a physical place, as a space for transformative experiences, and as a figurative device into their work to provide insight into the process of nation building in Austria. At the same time, it provides a vehicle to explore the inability of the Austrian nation to come to terms with the past and face the challenges of a postmodern life. Many Austrian writers have reinvented, revised, and reaffirmed current conceptions of wilderness in order to critique varying aspects of social, cultural, and political life in Austria. I explore the way in which literary texts shape and are shaped by cultural understandings of wilderness. My dissertation will not only shed light on the importance of these texts in endorsing, perpetuating, and shaping cultural understandings of wilderness, but it also will analyze their role in critiquing and dismantling the predominant commonplace notions of it. While some of the works deal directly with the physical wilderness within Austrian borders, others employ it as an imagined entity that affects all aspects of Austrian life. ii Dedication To my family, without whose support this would not have been possible.