ARO17: the Demise of Tigh Caol, an Eighteenth Century Drovers'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fnh Journal Vol 28

the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 28 2005 Naturalist Papers 5 Dunblane Weather 2004 – Neil Bielby 13 Surveying the Large Heath Butterfly with Volunteers in Stirlingshire – David Pickett and Julie Stoneman 21 Clackmannanshire’s Ponds – a Hidden Treasure – Craig Macadam 25 Carron Valley Reservoir: Analysis of a Brown Trout Fishery – Drew Jamieson 39 Forth Area Bird Report 2004 – Andre Thiel and Mike Bell Historical Papers 79 Alloa Inch: The Mud Bank that became an Inhabited Island – Roy Sexton and Edward Stewart 105 Water-Borne Transport on the Upper Forth and its Tributaries – John Harrison 111 Wallace’s Stone, Sheriffmuir – Lorna Main 113 The Great Water-Wheel of Blair Drummond (1787-1839) – Ken MacKay 119 Accumulated Index Vols 1-28 20 Author Addresses 12 Book Reviews Naturalist:– Birds, Journal of the RSPB ; The Islands of Loch Lomond; Footprints from the Past – Friends of Loch Lomond; The Birdwatcher’s Yearbook and Diary 2006; Best Birdwatching Sites in the Scottish Highlands – Hamlett; The BTO/CJ Garden BirdWatch Book – Toms; Bird Table, The Magazine of the Garden BirthWatch; Clackmannanshire Outdoor Access Strategy; Biodiversity and Opencast Coal Mining; Rum, a landscape without Figures – Love 102 Book Reviews Historical–: The Battle of Sheriffmuir – Inglis 110 :– Raploch Lives – Lindsay, McKrell and McPartlin; Christian Maclagan, Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary – Elsdon 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 28 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, University of Stirling – charity SCO 13270 and member of the Scottish Publishers Association. November, 2005. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University – M. Thomas (Chairman); Roy Sexton – Biological Sciences; H. Kilpatrick – Environmental Sciences; Christina Sommerville – Natural Sciences Faculty; K. -

Bandeath Holdings Ltd

National Planning Framework 4 Call for Ideas On behalf of Bandeath Holdings Ltd April 2020 Prepared by Stefano Smith Planning Project Ref: 100/01 | Rev: AA | Date: April 2020 E: [email protected] W: www.stefanosmithplanning.com NPF4 Call for Ideas – Bandeath Holdings Ltd Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Introduction..................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Background .................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Scope of Submission ..................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Structure ......................................................................................................................... 9 2 The Climate Challenge – a view from 2050 ............................................................................. 10 2.1 Introduction................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Whole Systems Approach ............................................................................................ 10 2.3 Added Value ................................................................................................................ -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

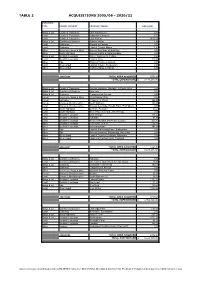

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

A91 (Blairlogie) Petition Update

Stirling Council Agenda Item No.7 Date of Environment & Housing Meeting: 12 September 2019 Committee Not Exempt A91 (Blairlogie) Petition Update Purpose & Summary Following a presentation of the A91 (Blairlogie) petition at the Environment & Housing Committee on 6 June 2019, Committee Members requested that officers investigate how a 30mph limit could be introduced to Blairlogie and provide a design for its installation. This report and its appendices present the findings of that investigation. Recommendations Committee is asked to: 1. note the contents of this report; 2. note the options presented; 3. note feedback from consultation with community; and 4. recommend a report to a future Finance & Economy Committee. Resource Implications There is no budget allocation for implementation of 30mph speed limits within the Traffic Management & Community Safety or Implementation of Accident Sites Remedial Programme budgets. Therefore, any decision to carry out works to allow for implementation of 30mph limits will require an additional capital allocation that will require to be considered through the Council’s budget process. Legal & Risk Implications and Mitigation Stirling Council, as the roads authority has a responsibility to set local speed limits in line with national guidance, direction and good practice. Failure to do so may leave Stirling Council open to legal action should an accident occur in an area where the speed limit has not been set in line with that guidance. 1. Background 1.1. The A91 is the primary route linking Stirling and St. Andrew’s. 1.2. Blairlogie is the first of six settlements on the A91, which run along the Hillfoots within Stirling and Clackmannanshire. -

"I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speth, Alana, ""I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624392. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-szar-c234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth Nicholson, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alana Speth Approved by the Committee L Committee Chair Pullen Professor James Whittenburg, History The College of William and Mary Professor LuAnn Homza, History The College of William and Mary • 7 i ^ i Assistant Professor Kathrin Levitan, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE The radical and complex changes that unfolded in the Scottish Highlands beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century have often been depicted as an example of mainstream British assimilation. -

Kilmodan Sculptured Stones Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC086 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90318) Taken into State care: 1978 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KILMODAN SCULPTURED STONES We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KILMODAN SCULPTURED STONES BRIEF DESCRIPTION This small but significant collection of sculptured stones lies within an 18th century burial aisle in the south-east corner of Kilmodan parish churchyard. -

Scottish Lowlands FD Strategic Plan 2007-2017

SCOTTISH LOWLANDS FOREST DISTRICT STRATEGIC PLAN 2007 – 2017 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 1 Contents 1 Planning framework 3 2 Description of the District 8 3 Evaluation of the previous District Strategic Plan 15 4 Identification and analysis of issues 16 5 Response to the issues, implementation and monitoring 30 Appendices 1 Evaluation of achievements (1999-2006) under previous Strategic Plan 49 2 List of local plans and guidance 61 3 Scheduled ancient monuments, sites of special scientific interest and ancient woodland sites 63 4 District map 5 Standard maps 67-77 6 Key issues cross-referenced to SFS themes 78 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 2 1 Planning framework 1.1 Introduction Forestry in Scotland is the responsibility of Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Government. Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) acts as the Scottish Government’s Forestry Department. Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES) is an executive agency of FCS with the role of managing the national forest estate according to FCS policies. Scottish Lowlands Forest District is the part of FES with responsibility for management of the estate in central Scotland. The aim of this Plan is to describe how the District will deliver its part of the Scottish Forestry Strategy (SFS 2006), which is the forest policy of the Scottish Government. The strategy articulates a vision for forestry in Scotland, to be met by 2025. Scottish Forestry Strategy Vision By the second half of this century, people are benefiting widely from Scotland's trees, woodlands and forests, actively engaging with and looking after them for the use and enjoyment of generations to come. -

The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses August 2015 Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland Christine B. Anderson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christine B., "Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 342. https://doi.org/10.7275/6944753.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/342 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A dissertation presented by CHRISTINE BROUGHTON ANDERSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Anthropology ©Copyright by Christine Broughton Anderson 2015 All Rights Reserved Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A Dissertation Presented By Christine Broughton Anderson Approved as to style and content by: H Martin Wobst, Chair Elizabeth Krause. Member Amy Gazin‐Schwartz, Member Robert Paynter, Member David Glassberg, Member Thomas Leatherman, Department Head, Anthropology DEDICATION To my parents. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with a sense of melancholy that I write my acknowledgements. Neither my mother nor my father will get to celebrate this accomplishment. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Gartmore Village Hall Development Phase 1

CELEBRATING 100 PROJECTS FROM THE FORTH VALLEY AND LOMOND LEADER PROGRAMME 2007-2013 IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF LIFE IN RURAL FORTH VALLEY AND LOMOND THROUGH REVITALISED COMMUNITIES AND ENHANCED NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS Photo © SEAG FOREWORD I joined Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER Local Action Group during the last programme, when it only covered rural Stirling and West Dunbartonshire, and continued as Vice Chair and the Chair for this programme. For this LEADER programme the area expanded to take in rural Falkirk, rural Clackmannanshire and part of West Dunbartonshire more than doubling the population we covered. The escalation in LEADER coverage drove us to expand the Local Action Group (LAG) including many more people who had not had LEADER coverage before. The transition process was ultimately successful and the LAG became a knowledgeable sounding board for applications to LEADER, approving over £3m worth of projects in the area. This transition from a small LEADER area to a much larger and more varied rural area would not have been nearly as successful without the leadership and friendly manner of Dereck Fowles, Chair of Rural Stirling LEADER and first Chair of Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER. Sadly, Dereck passed away in November 2013 at the rip old age of 86, eleven of those years having been spent supporting and leading us in LEADER. Dereck was a friendly and welcoming Chair with a quick wit that was always used to put people at ease. Always very generous with his time and absolutely committed to the improvement of the lives of people living in rural Scotland, Dereck, more than any other single person, helped make this LEADER programme a success and he will be sorely missed in the Forth Valley and Lomond area and in rural Scotland.