RE-COMMEMORATING 1644 the 360 Anniversary of the Jiashen Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

Manchus: a Horse of a Different Color

History in the Making Volume 8 Article 7 January 2015 Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color Hannah Knight CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Knight, Hannah (2015) "Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color," History in the Making: Vol. 8 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol8/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color by Hannah Knight Abstract: The question of identity has been one of the biggest questions addressed to humanity. Whether in terms of a country, a group or an individual, the exact definition is almost as difficult to answer as to what constitutes a group. The Manchus, an ethnic group in China, also faced this dilemma. It was an issue that lasted throughout their entire time as rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911) and thereafter. Though the guidelines and group characteristics changed throughout that period one aspect remained clear: they did not sinicize with the Chinese Culture. At the beginning of their rule, the Manchus implemented changes that would transform the appearance of China, bringing it closer to the identity that the world recognizes today. In the course of examining three time periods, 1644, 1911, and the 1930’s, this paper looks at the significant events of the period, the changing aspects, and the Manchus and the Qing Imperial Court’s relations with their greater Han Chinese subjects. -

Did the Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to The

religions Article Did the Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to the Spirits and to Heaven Standardize Manchu Shamanism? Xiaoli Jiang Department of History and Culture, Jilin Normal University, Siping 136000, China; [email protected] Received: 26 October 2018; Accepted: 4 December 2018; Published: 5 December 2018 Abstract: The Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to the Spirits and to Heaven (Manzhou jishen jitian dianli), the only canon on shamanism compiled under the auspices of the Qing dynasty, has attracted considerable attention from a number of scholars. One view that is held by a vast majority of these scholars is that the promulgation of the Manchu Rites by the Qing court helped standardize shamanic rituals, which resulted in a decline of wild ritual practiced then and brought about a similarity of domestic rituals. However, an in-depth analysis of the textual context of the Manchu Rites, as well as a close inspection of its various editions reveal that the Qing court had no intention to formalize shamanism and did not enforce the Manchu Rites nationwide. In fact, the decline of the Manchu wild ritual can be traced to the preconquest period, while the domestic ritual had been formed before the Manchu Rites was prepared and were not unified even at the end of the Qing dynasty. With regard to the ritual differences among the various Manchu clans, the Qing rulers took a more benign view and it was unnecessary to standardize them. The incorporation of the Chinese version of the Manchu Rites into Siku quanshu demonstrates the Qing court’s struggles to promote its cultural status and legitimize its rule of China. -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

Chen Chien-Sheng

Chen Chien-sheng Chen Chien-sheng. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Semantic Scholar profile for Chien-Sheng Chen, with fewer than 50 highly influential citations. Wireless location is to determine the position of the mobile station (MS) in wireless communication networks. Chen Sheng has always been obedient and never once deviated from the life course set for him by others. Everything changes when Cheng Mu--a literature professor--comes into his life. By accident, he discovers the young professor's secret. At the same time, the professor also finds out about Chen Sheng's unique talent. Their lives will never be the same again. Chen Sheng chapters. Chen Sheng Chapter 3.2 : Bar Danger. Chen Sheng Chapter 3 : Bar Danger. Chen Sheng Chapter 2 : Exchanging Secrets. Chen Sheng has always been obedient and never once deviated from the life course set for him by others. Everything changes when Cheng Mu--a literature professor--comes into his life. By accident, he discovers the young professor's secret. At the same time, the professor also finds out about Chen Sheng's unique talent. Their lives will never be the same again. Popular Manga UpdatesALL. Chen Sheng has always been obedient and never once deviated from the course set for him by his family and society. Everything changes when Cheng Mu--a literature professor--comes into his life. -

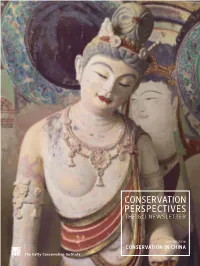

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

The Old Master

INTRODUCTION Four main characteristics distinguish this book from other translations of Laozi. First, the base of my translation is the oldest existing edition of Laozi. It was excavated in 1973 from a tomb located in Mawangdui, the city of Changsha, Hunan Province of China, and is usually referred to as Text A of the Mawangdui Laozi because it is the older of the two texts of Laozi unearthed from it.1 Two facts prove that the text was written before 202 bce, when the first emperor of the Han dynasty began to rule over the entire China: it does not follow the naming taboo of the Han dynasty;2 its handwriting style is close to the seal script that was prevalent in the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). Second, I have incorporated the recent archaeological discovery of Laozi-related documents, disentombed in 1993 in Jishan District’s tomb complex in the village of Guodian, near the city of Jingmen, Hubei Province of China. These documents include three bundles of bamboo slips written in the Chu script and contain passages related to the extant Laozi.3 Third, I have made extensive use of old commentaries on Laozi to provide the most comprehensive interpretations possible of each passage. Finally, I have examined myriad Chinese classic texts that are closely associated with the formation of Laozi, such as Zhuangzi, Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr. Lü), Han Feizi, and Huainanzi, to understand the intellectual and historical context of Laozi’s ideas. In addition to these characteristics, this book introduces several new interpretations of Laozi. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

The Case of Smallpox and the Manchus (1613-1795

Copyright © 2002 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 57.2 (2002) 177-197 [Access article in PDF] Disease And its Impact on Politics, Diplomacy, and the Military: The Case of Smallpox and the Manchus (1613–1795) Chia-Feng Chang One of the most dramatic events in Chinese history was the rise of the Qing dynasty in 1644. Scholars have suggested various reasons why the Manchus successfully conquered Ming China, but one important reason has long been neglected. An infectious disease, smallpox, played a key role in the story. Smallpox might have served as a barrier, preventing the success of the susceptible Manchus, both during the time of military conquest and in the years that followed. In this essay I explore how the Manchus responded to the danger of smallpox and how smallpox shaped the Manchu military, political, and diplomatic structures during the conquest and the first half of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). In the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) smallpox was rare among the peoples who lived beyond the northern borders of China, including the Manchus. For example, Zhang Jiebin (1563–1640), an eminent physician, stated that the northern peoples did not develop the disease. 1 A government official of the time, Xie Zhaozhe, also remarked that the Tartars did not suffer from smallpox. 2 As late as the Qing [End Page 177] dynasty, Zhu Chungu (1634–1718?), who was appointed to practice variolation amongst the Mongols during the Kangxi period (1662–1722), asserted that it was their nomadic lifestyle which protected them. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history.