Initial Environmental Examination: Mongar Accelerated Rural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View English PDF Version

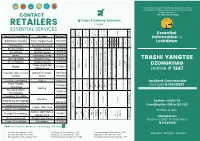

on ” 1247 17608432 17343588 Please stay alert. Chairperson His Majesty The King Hotline # 4141 Essential Lockdown Eastern COVID-19 Information Stay Home - Stay Safe - Save Lives DZONGKHAG Hotline # Dzongda Incident Commander Eastern COVID-19 Task Force Coordination Office (ECCO) It will undo everything that we have achieved so far. “ A careless person’s mistake will undo all our efforts. TRASHI YANGTSE Name Contact # Zone (Yangtse) Delivery time Delivery Day Order Day Rigney (Rigney including Hospital, RNR, NSC, BOD, 17641121 NRDCL ) 8:00 AM to 12:00 17834589/77218 PM 454 Baechen SATURDAY Retailers 17509633 SUNDAY ( 7:00 AM to 17691083 Main Town (below Dzong and Choeten Kora 12:00 PM to 3:00 6:00 PM) 17818250 area) PM 17282463 Baylling (above Dzong, including Rinchengang till 3:00 PM to 6:00 17699183 BCS) PM 6:00 AM to 17696122 Baylling, Baechen, Rigney and Main Town THURSDAY Vendors 5:00PM ( SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 Agriculture 6:00 AM to 17302242 From Serkhang Chu till Choeten Kora PM) 5:00PM 6:00 AM to MONDAY 17874349 Rigney & Baechen Zone (Yangtse and Doksum) THURSDAY Yangtse Vendors 5:00PM WEDNESDAY & SATURDAY ( Jomotshangkha Drungkhag -1210 Nganglam Drungkhag - 1195 Samdrupcholing Drungkhkag - 1191 Livestock 6:00 AM to 6:00 AM to 6:00 17532906 Main Town & Baylling Zone PM) 5:00PM TUESDAY & 77885806/77301 2:00 PM to 5:00 LPG Delivery Yangtse Throm TUESDAY & FRIDAY FRIDAY ( 9:00 AM 070 PM to 1:00 PM) Order & Delivery Schedule 17500690 FRIDAY ( Meat Shop Yangtse Throm 7:00 AM to 1:00PM SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 77624407 PM) Pharmacy 17988376 Doksum & Yangtse Throm As & when As & When / # 3 9 1 3 3 1 3 9 8 9 0 1 6 7 2 8 5 3 6 9 3 8 3 6 8 5 8 2 4 8 5 2 7 t 5 0 7 5 6 0 4 6 5 4 4 1 5 0 8 5 1 2 1 5 c 7 8 9 2 5 9 3 9 4 9 4 6 2 1 7 7 8 8 1 3 a 5 5 0 7 4 2 4 t 0 3 9 5 7 8 9 9 0 6 1 4 8 7 8 5 6 5 3 7 n 5 8 6 6 3 2 6 5 5 8 8 6 8 8 4 4 8 9 5 8 o 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 6 7 7 7 7 7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 C 1 . -

World Bank Document

Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Bhutan Poverty Mapping Report 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized National Statistics Bureau, Bhutan Poverty and Equity Global Practice, The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized December 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements: This report and the poverty map estimation was authored by Dung Doan (Consultant, The World Bank), in collaboration with the National Statistics Bureau (NSB) of Bhutan. The preparation of the report was led by Yeon Soo Kim (Economist, The World Bank). Benu Bidani (Practice Manger, The World Bank) and Chhime Tshering (Director, NSB) provided overall guidance to the team. Helpful comments and technical guidance were provided by Minh Cong Nguyen (Senior Data Scientist, The World Bank) and Paul Andres Corral Rodas (Data Scientist, The World Bank) and are gratefully acknowledged. Abbreviations BIC Bayesian Information Criterion BLSS Bhutan Living Standards Survey PHCB Population and Housing Census of Bhutan CI Confidence Interval GNHC Gross National Happiness Commission NSB National Statistics Bureau SE Standard Error SD Standard Deviation I. Introduction Bhutan has made great strides in reducing poverty over the last decade. The official national poverty rate declined from 23.2 percent in 2007 to 8.2 percent in 2017; most of this improvement came from rural areas with rural poverty decreasing from 30.9 to 11.9 percent during this period. This is particularly remarkable given a largely agrarian economy and the challenges arising from sparse population settlement patterns. However, there are large differences in poverty levels across Dzongkhags. A good understanding of the geographic distribution of poverty is of great importance to guide policies to realize Gross National Happiness – Bhutan’s development philosophy that emphasizes a holistic and inclusive approach to sustainable development. -

Eastern Bhutan Circuit 1: Tourism Development Plan Mongar, Lhuentse, and Trashiyangtse

Eastern Bhutan Circuit 1: Tourism Development Plan Mongar, Lhuentse, and Trashiyangtse DRAFT Beyond Green Travel LLC Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 17 a. Bhutan in the Global Tourism Market ............................................................................. 17 b. Purpose and Scope of Work ............................................................................................. 20 c. Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 21 d. Market Analysis and Age Demographic ......................................................................... 23 e. Gender and Vulnerability ................................................................................................... 25 f. Strategy Overview ................................................................................................................ 27 II. Introduction to the Circuit 1 Eastern Dzongkhags of Mongar, Lhuentse, and Trashiyangtse ....................................................................................................................... 27 a. Introduction to -

Farming and Biodiversity of Pigs in Bhutan

Animal Genetic Resources, 2011, 48, 47–61. © Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2011 doi:10.1017/S2078633610001256 Farming and biodiversity of pigs in Bhutan K. Nidup1,2, D. Tshering3, S. Wangdi4, C. Gyeltshen5, T. Phuntsho5 and C. Moran1 1Centre for Advanced Technologies in Animal Genetics and Reproduction (REPROGEN), Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Australia; 2College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, Lobesa, Bhutan; 3Department of Livestock, National Pig Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Thimphu, Bhutan; 4Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Lingmithang, Bhutan; 5Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Gelephu, Bhutan Summary Pigs have socio-economic and cultural importance to the livelihood of many Bhutanese rural communities. While there is evidence of increased religious disapproval of pig raising, the consumption of pork, which is mainly met from imports, is increasing every year. Pig development activities are mainly focused on introduction of exotic germplasm. There is an evidence of a slow but steady increase in the population of improved pigs in the country. On the other hand, indigenous pigs still comprise 68 percent of the total pig population but their numbers are rapidly declining. If this trend continues, indigenous pigs will become extinct within the next 10 years. Once lost, this important genetic resource is largely irreplaceable. Therefore, Government of Bhutan must make an effort to protect, promote and utilize indigenous pig resources in a sustainable manner. In addition to the current ex situ conservation programme based on cryopre- servation of semen, which needs strengthening, in situ conservation and a nucleus farm is required to combat the enormous decline of the population of indigenous pigs and to ensure a sustainable source of swine genetic resources in the country. -

Contact List of Cable TV Operators

List of Cable TV Operators Sl. License Name of Cable Contact Person and Details Area of Operation Dzongkhag No. No. TV Operator Mrs. Sonam Wangmo Tobgyel Cable Sat Club Contact #: 17111757, 17897373, 1 603000001 Phuentsholing Thromde Chhukha Service 252991/252806F. Email: [email protected] Mrs. Yangchen Lhamo Norling Cable Contact #: 17110826 2 603000002 Thimphu Thromde Thimphu Service Telephone #: 326422 Email: [email protected] Mr. Tshewang Rinzin Dogar Cable 3 603000003 Contact #: 17775555 Dawakha of Dogar Gewog Paro Service Email: [email protected] Mr. Tshering Norbu Contact #: #: 177701770 Phuentsholing Thromde Tshela Cable Email: [email protected] 4 603000004 Phuentsholing Gewog and Chhukha Service Rinchen Wangdi Sampheling Gewog Contact #: 17444333 Email: [email protected] Mr. Basant Gurung Norla Cable 5 603000005 Contact #: 17126588 Samkhar and Surey Sarpang Service Email: [email protected] Wangcha Gewog, Dhopshari Gewog Mr. Tshewang Namgay and Mr. Ugyen Dorji Sigma Cable Doteng Gewog, Lango Gewog, 6 603000006 Contact #: 17110772/77213777 Paro Service Lungnyi Email: [email protected] Gewog, Shaba Gewog, Hungrel Gewog. Sl. License Name of Cable Contact Person and Details Area of Operation Dzongkhag No. No. TV Operator Samtse Gewog, Tashicholing Gewog Mr. Singye Dorji Sangacholing Gewog, Ugyentse 7 603000007 SKD Cable Contact #: 05-365243/05-365490 Gewog Samtse Email: [email protected] Norbugang Gewog, Pemaling Gewog and Namgaycholing Gewog Ms. Sangay Dema SNS Cable 8 603000008 Contact #: 17114439/17906935 Gelephu Thromde Sarpang Service Email: [email protected] Radi Gewog, Samkhar Gewog, Ms. Tshering Dema Tshering Norbu Bikhar 9 603000009 Contact #: 17310099 Trashigang Cable Gewog, Galing Gewog, Bidung Email: [email protected] Gewog, Songhu Gewog Mr. Tandi Dorjee Tang Gewog, Ura Gewog, TD Cable 10 603000010 Contact #: 17637241 Choekor Bumthang Network Email: [email protected] Mea Mr. -

Dzongkhag LG Constituency 1. Chhoekhor Gewog 2. Tang Gewog

RETURNING OFFICERS AND NATIONAL OBSERVERS FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS, 2016 Placement for LG Elections Phone Name Email ID Number Dzongkhag LG Constituency 1. Chhoekhor Gewog [email protected] 17968147 2. Tang Gewog [email protected] Dechen Zam(RO) Bumthang 3. Chhumig Gewog 17626693 [email protected] or 4. Ura Gewog 77308161 [email protected] 5. Bumthang Thromde Ngotshap 1.Chapchha Gewog 17116965 [email protected] Phendey Wangchuk(RO) Chukha 2.Bjagchhog Gewog 3.Getana Gewog 17601601 [email protected] 1. Darla Gewog 17613462 [email protected] 2. Bongo Gewog Singey Phub(RO) Chukha 3.Geling Gewog 17799552 [email protected] 4. Doongna Gewog 1.Samphelling Gewog 17662187 [email protected] 2. Phuentshogling Gewog Tenzin Wangchuk(RO) Chukha 3.Maedtabkha Gewog 77219292 [email protected] 4.Loggchina Gewog 1. Tseza Gewog 77292650 [email protected] 2. Karna Gewog Ugyen Lhamo(RO) Dagana 3. Gozhi Gewog 17661755 [email protected] 4. Dagana Thromde Ngotshap 1. Nichula Gewog 17311539 [email protected] Dr Jambay Dorjee(RO) Dagana 2. Karmaling Gewog 3. Lhamoi_Dzingkha Gewog 17649593 [email protected] 1. Dorona Gewog 17631433 [email protected] Leki(RO) Dagana 17631433 [email protected] 2. Gesarling Gewog Leki(RO) Dagana 3. Tashiding Gewog 17831859 [email protected] 4. Tsenda- Gang Gewog 1. Largyab Gewog 17609150 [email protected] 2. Tsangkha Gewog Tshering Dorji(RO) Dagana 3. Drukjeygang Gewog 17680132 [email protected] 4. Khebisa Gewog 1. Khamaed Gewog 17377018 [email protected] Ugyen Chophel(RO) Gasa 2. Lunana Gewog 17708682 [email protected] 1. -

MID TERM REVIEW REPORT (11Th FYP) November, 2016

MID TERM REVIEW REPORT (11th FYP) November, 2016 ELEVENTH FIVE YEAR PLAN (2013-2018) MID TERM REVIEW REPORT GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS COMMISSION ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN NOVEMBER 2016 Gross National Happiness Commission Page 1 MID TERM REVIEW REPORT (11th FYP) November, 2016 Gross National Happiness Commission Page 2 MID TERM REVIEW REPORT (11th FYP) November, 2016 Gross National Happiness Commission Page 3 MID TERM REVIEW REPORT (11th FYP) November, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................... 02 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 05 METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH ......................................................................................... 06 AN OVERVIEW OF ELEVENTH PLAN MID-TERM ACHIEVEMENTS ............................. 06 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................... 06 STATUS OF THE 11th FYP OBJECTIVE ..................................................................................... 07 ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE ...................................................................................................... 09 SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT TRENDS ............................................................................................ 12 PLAN PERFORMANCE: CENTRAL SECTORS, AUTONOMOUS AGENCIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ............................................................................................................. -

Impact of Post-Harvest Training on Farmers in Lhuntse, Mongar, Trashigang and Trashiyangtse Dzongkhags

Impact of Post-Harvest Training on Farmers in Lhuntse, Mongar, Trashigang and Trashiyangtse Dzongkhags Yeshi Samdrup Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Masters in Development Practice 7 August 2019 Royal University of Bhutan College of Natural Resources Lobesa: Punakha BHUTAN Declaration I hereby declare that this research entitled “Impact of Post-Harvest Training on Farmers in Lhuntse, Mongar, Trashigang and Trashiyangtse Dzongkhags” is an original work and I have not committed, as far as to my knowledge, any academic dishonesty or remedied to plagiarism in writing the report. All the information sources, supports and assistance received during the course of the study are duly acknowledged. Student’s signature: ............................................ Date: ............................ i Acknowledgements The success and final outcome of this research required a lot of guidance and support from many people and I would like to thank all the people who wholeheartedly spared their time in sharing what they knew on this topic. I would like to firstly thank IFAD-MDP Universities Win-Win Partnership for funding and guiding us to complete this research. I respect and genuinely thank my supervisor Dr. Tulsi Gurung [College of Natural Resources] and Mr. Sangay Choda [CARLEP] for their unwavering support and guidance and in every step of this study. My sincere thanks goes to the Commercial Agriculture and Livelihood Enhancement Programme (CARLEP) and Agriculture and Research Development Centre (ARDC) for providing valuable information for the project. I shall also remain grateful to twelve gewog’s administration, specifically the gup, Tshokpas, and farmers for helping with the necessary information and cooperation and their time and patience to take part in this Survey. -

Market Infrastructure Inventory 2016

Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Summary of Agricultural Market Infrastructure in the country by Dzongkhag and Type .................... 3 III. Details of Farm Shops established as of June 30, 2016. ................................................................... 4 IV. Agricultural Market Infrastructure Inventory Details (2016) ............................................................ 6 1. Bumthang Dzongkhag ....................................................................................................................... 6 2. Chukha Dzongkhag ............................................................................................................................ 7 3. Dagana Dzongkhag ............................................................................................................................ 8 4. Gasa Dzongkhag ................................................................................................................................ 9 5. Haa Dzongkhag ............................................................................................................................... 10 6. Lhuentse Dzongkhag ....................................................................................................................... 11 7. Mongar Dzongkhag ........................................................................................................................ -

Statistical Yearbook 2017 of Royal Bhutan Police Is the 6Th Edition of Its Kind Which Is Published Annually

PREFACE The Statistical Yearbook 2017 of Royal Bhutan Police is the 6th edition of its kind which is published annually. The main purpose of the Statistical Yearbook is to provide in a single volume a comprehensive compilation of available statistics on crime in the country registered with the Royal Bhutan Police. Ever since the compilation of data for the Statistical Yearbook series was initiated in 2012, improvements are consistently made to enhance its contents and coverage. The new data relating to criminal offences and Royal Bhutan Police are added as and when available. Most of the statistics presented in the yearbook are extracted from more detailed database maintained by Crime and Operations Branch. The Crime and Operations Branch collects statistics from various field Divisions and Police Stations in the country, which are further verified for publication. Thimphu Traffic Division, Fire Service Division, and Private Arms Licensing Unit have also contributed their statistics for the publication. We expect that the data in the yearbook will serve as the principal source of information for planners, policy makers, researchers and academicians. More importantly, it is expected that statistics in this publication will be used by the officers and men of RBP to plan and guide their policing actions to further reduce and prevent crime in future. Through this initiative, we also hope that the maintenance of information and updates will become more systematic and efficient. We expect that there may be certain deficiencies in terms of content and coverage. However, continuous efforts will be made to improve its content, coverage and quality in the future publications. -

Post-Zhabdrung Era Migration of Kurmedkha Speaking People in Eastern Bhutan *

Post-Zhabdrung Era Migration of Kurmedkha Speaking People in Eastern Bhutan * Tshering Gyeltshen** Abstract Chocha Ngacha dialect, spoken by about 20,000 people, is closely related to Dzongkha and Chökey. It was Lam Nado who named it Kurmedkha. Lhuntse and Mongar dzongkhags have the original settlement areas of Kurmedkha speaking ancestors. Some families of this vernacular group migrated to Trashigang and Trashi Yangtse in the post-Zhabdrung era. The process of family migrations started in the 17th century and ended in the early part of the 20th century. This paper attempts to trace the origins of Kurmedkha speaking population who have settled in these two dzongkhags. Kurmedkha speakers and their population geography Bhutanese administrators and historians used the north- south Pelela mountain ridge as a convenient geographical reference point to divide the country into eastern and western regions. Under this broad division, Ngalop came to be regarded as inhabitants west of Pelela, and those living east of Pelela are known as Sharchop.1 The terms Sharchop and Ngalop naturally evolved out of common usage, mostly among * This paper is an outcome of my field visits to Eastern Bhutan in 2003. ** Senior Lecturer in Environmental Studies, Sherubtse College, Royal University of Bhutan. 1 From the time of the first Zhabdrung until recent years, people of Kheng (Zhemgang), Mangdi (Trongsa), Bumthang, Kurtoe (Lhuntse), Zhongar (Mongar), Trashigang, Trashi Yangtse and Dungsam (Pema Gatshel and Samdrup Jongkhar) who live in east of Pelela were all known as Sharchop, meaning the Easterners or Eastern Bhutanese. However, word has lost its original meaning today. The natives who speak Tshanglakha or Tsengmikha are now called Sharchop. -

Nu 2B Freed up for Covid-19 Activities During the Lockdown

SATURDAY KUENSELTHAT THE PEOPLE SHALL BE INFORMED AUGUST 15 COVID-19: Bhutan: 131 | Global: 21,088,317 | Recovered: 13,735,501 | Death: 757,650 | US: 5,415,666 India: 2,464,316 | West Bengal: 1,07,323 | Assam: 71,795 | Arunachal Pradesh: 2,512 | Sikkim: 931 Red Zone Phuentsholing sees three more cases Delivery of essentials a failure, say residents Rajesh Rai | Phuentsholing With three new cases detected yesterday, Phuent- sholing has now 16 confirmed Covid-19 positive cases. All are from the Mini Dry Port (MDP). Two men and a woman, who are the primary contacts of the positive case in Phuentsholing, were all found to be Covid-19 positive yesterday. Health ministry said they are from the MDP and not from the community. Kuensel sources said that the woman is a sweeper at the MDP. She also worked at the MDP canteen. By late yesterday evening, rumours that three policemen in Phuentsholing had been infected with the virus had gone viral. Kuensel sources said that one of the two men is a traffic policeman. However, Kuensel couldn’t confirm On the frontline: Two mobile health clinic teams from the Trongsa hospital has been providing essential this officially. health services to the people of the town and nearby areas. In the last three days, they have covered more Meanwhile, the lockdown has brought the than 100 people. country’s largest commercial town to a standstill. Although figures couldn’t be confirmed, Kuensel learned there were Bhutan bound trucks stuck across the border. Many trucks are also stranded at the MDP.