AB-2012-065 Aviation Short Investigation Bulletin Issue 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results from Public Consultation

1 Regional Plan (Update) 2016-2020 Results from Public Consultation 169 survey respondents: Which industry do you represent? Transport, logistics and warehousing 0.0% Tourism, accommodation and food services 11.8% Retail 2.4% Public services 8.3% Professional, scientific and technical services 14.8% Other 5.9% Not for profit 21.9% Media and telecommunications 1.8% Manufacturing 2.4% Health care, aged care and social assistance 8.3% Food growers and producers 4.1% Financial and insurance services 3.6% Electricity, gas, water and waste services 1.2% Education and training 8.9% Construction 0.6% Arts 4.1% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Which local government area do you live in? Outside the region 3.0% Coffs Harbour 35.5% Bellingen 8.3% Nambucca 13.6% Kempsey 14.8% Port Macquarie -… 18.9% Greater Taree 5.9% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 2 Careers advice linked to traineeships and apprenticeships Issue: Youth unemployment is high and large numbers of young people leave the region after high school seeking career opportunities, however, skills gaps currently exist in many fields suited to traineeships and apprenticeships. Target outcome: To foster employment and retention of more young people by providing careers advice on local industries with employment potential, linked with more available traineeships and apprenticeships. Key points: - Our region’s youth unemployment rate is 50% higher than the NSW state average. - There is a decline in the number of apprenticeships being offered in the region. - The current school based traineeship process is overly complicated for students, teachers and employers. -

Premium Location Surcharge

Premium Location Surcharge The Premium Location Surcharge (PLS) is a levy applied on all rentals commencing at any Airport location throughout Australia. These charges are controlled by the Airport Authorities and are subject to change without notice. LOCATION PREMIUM LOCATION SURCHARGE Adelaide Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Alice Springs Airport 14.5% on time and kilometre charges Armidale Airport 9.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Avalon Airport 12% on all rental charges except fuel costs Ayers Rock Airport & City 17.5% on time and kilometre charges Ballina Airport 11% on all rental charges except fuel costs Bathurst Airport 5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Brisbane Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Broome Airport 10% on time and kilometre charges Bundaberg Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Cairns Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Canberra Airport 18% on time and kilometre charges Coffs Harbour Airport 8% on all rental charges except fuel costs Coolangatta Airport 13.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Darwin Airport 14.5% on time and kilometre charges Emerald Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Geraldton Airport 5% on all rental charges Gladstone Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Grafton Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Hervey Bay Airport 8.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Hobart Airport 12% on all rental charges except fuel costs Kalgoorlie Airport 11.5% on all rental -

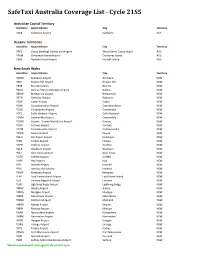

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

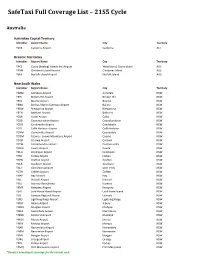

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Master Plan 2010 V1.0 June 2010

“Gateway to the Mid North Coast” MASTER PLAN 2010 June 2010 PORT MACQUARIE AIRPORT MASTER PLAN 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Master Plan has been prepared in consultation with a broad range of airport stakeholders and the local community. Technical input and planning advice has been provided by consultants Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd (previously Connell Wagner) and Airport Master Planning Consultants Pty Ltd. Port Macquarie Airport gratefully acknowledges the cooperation and input from all organisations and individuals who participated in the preparation of this Plan and to those who submitted comments in response to the Master Plan Discussion Paper published in June 2009. COPYRIGHT Copyright in all aspects of the Port Macquarie Airport Master Plan (Plans) and other documents prepared by or on behalf of Port Macquarie – Hastings Council in relation to the Master Plan remain the property of the Port Macquarie – Hastings Council or the original author of that work. The Plans, nor any part of them, may not be used, copied, reproduced or otherwise dealt with in any manner which may infringe the rights of the holders of that copyright by any party without the prior express and written authorisation of Port Macquarie – Hastings Council. DISCLAIMER Whilst Port Macquarie – Hastings Council has attempted to make the information within the Plans as accurate as possible, the Plans are provided in good faith and for general information purposes only. Port Macquarie – Hastings Council makes no representation or warranties of any kind with regard to the completeness, accuracy, reliability or suitability of the Plans for any purpose whatsoever. Any third party who relies on the Plans or the information contained within them does so entirely at their own risk. -

DNC Destination Management Plan

North Coast Destination Management Plan 2018 to 2021 9 March 2018 Disclaimer The information contained in this report is intended only to inform and should not be relied upon for future investment or other decisions. It is expected that any investment decisions made using these specific recommendations will be fully analysed and appropriate due iligenced undertaken. In the course of our preparation of the North Coast Destination Management Plan 2018 to 2021, recommendations have been made using information and assumptions provided by many sources and from the methodology adopted for this Plan. The authors accept no responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or resultant consequences including any loss or damage arising from reliance on the information contained in this report. It should also be noted that visitation data presented in this Plan for the North Coast is an approximation of the administrative boundaries of the North Coast. Definitions can vary between data sources and over time and data should be used with caution. 2 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land that the geographic scope of this Plan covers and elders past and present. This Destination Management Plan has been prepared by Destination North Coast management (Phil Harman, General Manager and Jacquie Burnside, Business Development Manager) in collaboration with consultants Meredith Wray (Wray Sustainable Tourism Research) and Claire Ellis (Claire Ellis Consulting). ACRONYMS Destination North Coast management and consultants wish to thank Destination New South Wales and the Destination North Coast Board for their support and strategic advice to guide and inform the development of this Plan. -

Cabin Crew) Pre-Course Information and Learning

14 COMPASS ROAD, JANDAKOT PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING IF YOU HAVE RECEIVED AN OFFER FOR THE FOLLOWING COURSE National ID: AVI30219 Course: AZS9 Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) Pre-Course Information and Learning Course Outline: The Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) course requires you to be able to work effectively in a team environment as part of a flight crew, work on board a Boeing 737 in the aircraft cabin and perform first aid in an aviation environment. Part of your training will require you to be able to swim fully clothed to conduct emergency procedures in a raft. Self-defence skills are taught as part of the curriculum which may require you to be in close proximity to the trainees. When you complete the Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) you will be recruitment-ready for an exciting career as a flight attendant or cabin crew member. You will gain valuable experience and skills in emergency response drills, first aid, responsible service of alcohol, teamwork and customer service, and preparation for cabin duties. You will gain confidence in dealing with difficult passengers on an aircraft with crew member security training. This course is specifically designed for those seeking an exciting career as a cabin crew member (flight attendant). This course has been developed in conjunction with commercial airlines and experienced cabin crew training managers to meet current aviation standards and will thoroughly prepare you to be successful in the airline industry. South Metropolitan TAFE has a Boeing 737 which will be used for the majority of your practical training. -

Good-Bye^ 2020

SUMMER 2020 / 21 Good-bye^ 2020 Seems like yesterday that the P.M. delivered his memorable 22 March 2020 address, announcing restrictions that closed public venues, cafes and restaurants and advised against non-essential travel. Globally, the aviation industry spiralled into freefall; grounded at best, insolvent at worst, with our own Airport terminal forced to close on 16 April without any RPT flights. On 15 May, Qantas resumed a twice-weekly service to Sydney, via Coffs Harbour, and we have been steadily improving since. We are grateful to see signs of life returning to the Airport and now offer 23 Image: COVID-19 emptied the Airport car park in 2020 services per week to Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra and Lord Howe Island, catering for over 1000 passengers a week. We are particularly pleased to welcome back our business partners and their staff and are thinking of those yet to return. It has been a tough year, yet despite all the challenges the year has delivered some great news. Aircraft operators would be delighted to know that the Airport received $3.5 million to support the development of a Stage 1 Code A parallel taxiway (see the article below on the Parallel Taxiway for further information). The Airport was also awarded $140,000 to improve our energy efficiency and install rooftop solar panels on the terminal in 2021 under the State Government’s Local Roads and Community Infrastructure Grant. For service to medicine and aviation, Dr David Cooke was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) in this year's Queen's Birthday honours list. -

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects 1 COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER Restart NSW Local and Community While every reasonable effort has been made Infrastructure Projects to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, Infrastructure NSW, its © July 2019 State of New South Wales agents and employees, disclaim any liability to through Infrastructure NSW any person in response of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to This document was prepared by Infrastructure be done in reliance upon the whole or any part NSW. It contains information, data and images of this document. Please also note that (‘material’) prepared by Infrastructure NSW. material may change without notice and you should use the current material from the The material is subject to copyright under Infrastructure NSW website and not rely the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and is owned on material previously printed or stored by by the State of New South Wales through you. Infrastructure NSW. For enquiries please contact [email protected] This material may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial Front cover image: Armidale Regional use, providing the meaning is unchanged and Airport, Regional Tourism Infrastructure its source, publisher and authorship are clearly Fund and correctly acknowledged. 2 Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects The Restart NSW Fund was established by This booklet reports on local and community the NSW Government in 2011 to improve infrastructure projects in regional NSW, the economic growth and productivity of Newcastle and Wollongong. The majority of the state. -

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects 1 COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER Restart NSW Local and Community While every reasonable effort has been made Infrastructure Projects to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, Infrastructure NSW, its © July 2019 State of New South Wales agents and employees, disclaim any liability to through Infrastructure NSW any person in response of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to This document was prepared by Infrastructure be done in reliance upon the whole or any part NSW. It contains information, data and images of this document. Please also note that (‘material’) prepared by Infrastructure NSW. material may change without notice and you should use the current material from the The material is subject to copyright under Infrastructure NSW website and not rely the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and is owned on material previously printed or stored by by the State of New South Wales through you. Infrastructure NSW. For enquiries please contact [email protected] This material may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial Front cover image: Armidale Regional use, providing the meaning is unchanged and Airport, Regional Tourism Infrastructure its source, publisher and authorship are clearly Fund and correctly acknowledged. 2 Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects The Restart NSW Fund was established by This booklet reports on local and community the NSW Government in 2011 to improve infrastructure projects in regional NSW, the economic growth and productivity of Newcastle and Wollongong. The majority of the state. -

Runway Excursions ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT Aviation Research and Analysis Report – AR-2008-018(2) Final

An Australian perspective An Australian excursions and consequences 2: Minimising the of runway Part likelihood excursions Runway ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT Aviation Research and Analysis Report – AR-2008-018(2) Final Runway excursions Part 2: Minimising the likelihood and consequences of runway excursions An Australian perspective AR-2008-048.indd 1 17/06/09 10:03 AM ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT Aviation Research and Analysis Report AR-2008-018(2) Final Runway excursions Part 2: Minimising the likelihood and consequences of runway excursions An Australian perspective - i - Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967. Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 62 Northbourne Ave, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory, 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2009. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton, ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN and formal report title: see ‘Document retrieval information’ on page v - ii - CONTENTS THE AUSTRALIAN TRANSPORT SAFETY BUREAU ................................ -

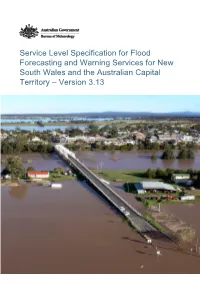

NSW Service Level Specification

Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory – Version 3.13 Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory This document outlines the Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services provided by the Commonwealth of Australia through the Bureau of Meteorology for the State of New South Wales in consultation with the New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Flood Warning Consultative Committee. Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales Published by the Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 (03) 9669 4000 www.bom.gov.au With the exception of logos, this guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Australia Attribution Licence. The terms and conditions of the licence are at www.creativecommons.org.au © Commonwealth of Australia (Bureau of Meteorology) 2013. Cover image: Major flooding on the Hunter River at Morpeth Bridge in June 2007. Photo courtesy of New South Wales State Emergency Service Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2 Flood Warning Consultative Committee .......................................................................... 4