Seeing the Scars of Slavery in the Natural Environment JAMES RIVER PARK SYSTEM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

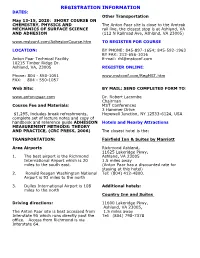

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

Fugitive Slaves and the Legal Regulation of Black Mississippi River Crossing, 1804–1860

Strengthening Slavery’s Border, Undermining Slavery: Fugitive Slaves and the Legal Regulation of Black Mississippi River Crossing, 1804–1860 BY JESSE NASTA 16 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2017 In 1873, formerly enslaved St. Louisan James master’s consent, or of the passenger’s free status, P. Thomas applied for a United States passport. persisted until the Civil War.3 After collecting the passport at his attorney’s office, Yet, while the text of the Missouri statute Thomas hurried home “to take a look at it” because remained fairly constant, its meaning changed over he had “never expected to see” his name on such a the six tumultuous decades between the Louisiana document. He marveled that this government-issued Purchase and the Civil War because virtually passport gave him “the right to travel where he everything else in this border region changed. The choose [sic] and under the protection of the American former Northwest Territory, particularly Illinois, flag.” As Thomas recalled in his 1903 autobiography, was by no means an automatic destination for those he spent “most of the night trying to realize the great escaping slavery. For at least four decades after the change that time had wrought.” As a free African Northwest Ordinance of 1787 nominally banned American in 1850s St. Louis, he had been able to slavery from this territory, the enslavement and cross the Mississippi River to Illinois only when trafficking of African Americans persisted there. “known to the officers of the boat” or if “two or three Although some slaves risked escape to Illinois, reliable citizens made the ferry company feel they enslaved African Americans also escaped from this were taking no risk in carrying me into a free state.”1 “free” jurisdiction, at least until the 1830s, as a result. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 NRHP Listed: 5/3/2019 1. Name of Property Historic name: Manchester Trucking and Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: VDHR File #127-6519 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Primarily along Commerce Road, Gordon Ave., and Dinwiddie Ave City or town: Richmond State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic -

Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Smith College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharron, "Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Renee Smith Richmond, Virginia Master of Liberal Arts, University of Richmond, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, 1989 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by Sharron R. Smith ABSTRACT The Virginia State Constitution of 1869 mandated that public school education be open to both black and white students on a segregated basis. In the city of Richmond, Virginia the public school system indeed offered separate school houses for blacks and whites, but public schools for blacks were conducted in small, overcrowded, poorly equipped and unclean facilities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, public schools for black students in the city of Richmond did not change and would not for many decades. -

For Sale | Shockoe Bottom Office and Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR SALE | SHOCKOE BOTTOM OFFICE AND MULTIFAMILY 1707 EAST MAIN STREET Richmond VA 23223 $750,000 PID: E0000109004 Ground and Lower Level Office Space 2 Residential Units on Second Level 4,860 SF Office Space B-5 Central Business Zoning Pulse BRT Corridor Location 0.05 AC Parcel Area Opportunity Zone PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS* 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 2 8 SHOCKOE BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD RESIDENTIAL UNITS 10 PULSE CORRIDOR PLAN 11 RICHMOND METRO AREA 12 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 13 RICHMOND MAJOR EMPLOYERS 4,860 SF 14 DEMOGRAPHICS 15 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM B-5 CENTRAL BUSINESS ZONING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 2008 RENOVATION Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of the 1707 E Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Golden Hammer Awards

Golden Hammer Awards 1 WELCOME TO THE 2018 GOLDEN HAMMER AWARDS! Storefront for Community Design and Historic You are focusing on blight and strategically selecting Richmond welcome you to the 2018 Golden Hammer projects to revitalize at risk neighborhoods. You are Awards Ceremony! As fellow Richmond-area addressing the challenges to affordability in new and nonprofits with interests in historic preservation and creative ways. neighborhood revitalization, we are delighted to You are designing to the highest standards of energy co-present these awards to recognize professionals efficiency in search of long term sustainability. You are working in neighborhood revitalization, blight uncovering Richmond’s urban potential. reduction, and historic preservation in the Richmond region. Richmond’s Golden Hammer Awards were started 2000 by the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Tonight we celebrate YOU! Neighborhoods. Historic Richmond and Storefront You know that Richmond has much to offer – from for Community Design jointly assumed the Golden the tree-lined streets of its historic residential Hammers in December 2016. neighborhoods to the industrial and commercial We are grateful to you for your commitment to districts whose collections of warehouses are attracting Richmond, its quality of life, its people, and its places. a diverse, creative and technologically-fluent workforce. We are grateful to our sponsors who are playing You see the value in these neighborhoods, buildings, important roles in supporting our organizations and and places. our mission work. Your work is serving as a model for Richmond’s future Thank you for joining us tonight and in our effort to through the rehabilitation of old and the addition of shape a bright future for Richmond! new. -

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping . -

Caryl Phillips's Crossing the River

Crossing and the Letter: Caryl Phillips’s Crossing the River TOKIZANE Sanae1 Caryl Phillips’s 1993 novel Crossing the River is one of his ambitious explorations of the history of the African Americans. The title of the novel obviously invokes the idea of travel or voyage, traversing the distance, or journey across the boundary. It may be justifiable, therefore, to interpret it as representing the Middle Passage, the Atlantic journey undertaken by slave ships, and to read the novel as an intricate dramatization of the traumatic experience of slave trade.“Crossing the river,”however, implicates more than that. The stories of the novel include many crossings of the opposite directions. They depict not only the various lives of African descendents, but even the journey of a captain of a slave ship. And“crossing”touches the problems of border or trespass. It is true that historical and traumatic journey is one of the key critical concepts for reading this work and it may be a due course to start here, but the world of the novel temporally and spatially overreaches the problematic passage. The idea is not passing, but crossing. I focus on the title word“crossing”and argue that the question of crossing could open up a radical move. In this novel, in particular in the first section,“The Pagan Coast,”crossing is related with the meaning and function of the letter, the symbolic and practical bearing of which I believe will introduce us to the new and imaginative meaning of diaspora. (1) TheMiddlePassage Before going into the main argument, I would like to examine the diverse ideas of the Middle Passage and see how it can be developed into crossing. -

Shockoe Bottom Shockoe Slip Financial District Capitol Square

Short Pump 5 via I-64West DAVE & BUSTER’S Historic Jackson Ward MAMA J’S 7 City Center VCU Medical BUZ & NED’S RICHMOND ON Center 3 REAL BARBECUE Historic Broad BROAD CAFÉ 12 14 VAGABOND via Broad Street 6 LA GROTTA Street RAPPAHANNOCK 11 10 PASTURE Capitol 13 SPICE OF INDIA Square NOTA BENE 9 Shockoe Bottom CAPITAL ALE Shockoe Slip Historic Monroe Ward HOUSE 4 BOTTOMS UP BOOKBINDERS 1 2 PIZZA Financial District MORTON’S 8 MAP COURTESY VENTURE RICHMOND AND ELEVATION ADVERTISING BOOKBINDER’S SEAFOOD & BOTTOMS UP PIZZA BUZ AND NED’S REAL BARBECUE CAPITAL ALE HOUSE DAVE & BUSTER’S LA GROTTA STEAKHOUSE 1 Shockoe Bottom 2 Boulevard Gateway 3 Financial District 4 Short Pump 5 City Center 6 Shockoe Bottom 1700 Dock Street 1119 N. Boulevard 623 E. Main Street 4001 Brownstone Blvd., 529 E. Broad Street 2306 E. Cary Street 804.644.4400 804.355.6055 804.780.ALES Glen Allen 804.644.2466 804.643.6900 bottomsuppizza.com buzandneds.com capitalalehouse.com 804.967.7399 lagrottaristorante.com bookbindersrichmond.com daveandbusters.com Monday–Wednesday, 11 a.m.–10 p.m. Sunday-Thursday 11 a.m.–9 p.m. Monday–Sunday, 11 a.m.–1:30 a.m. Lunch: Monday–Friday, 11:30 a.m.– Monday–Thursday, 5 p.m.–8:30 p.m. Thursday & Sunday, 11 a.m.–11 p.m. Friday & Saturday 11 a.m.–10 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Friday & Saturday, 11 a.m.–midnight Sunday–Tuesday, 11 a.m.–11 p.m. Dinner: Monday–Thursday, 5 p.m.– Friday & Saturday, 5 p.m.–9 p.m. -

Creighton Phase a 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223

Market Feasibility Analysis Creighton Phase A 3100 Nine Mile Road Richmond, Virginia 23223 Prepared For Ms. Jennifer Schneider The Community Builders, Incorporated 1602 L Street, Suite 401 Washington, D.C., 20036 Authorized User Virginia Housing 601 South Belvidere Street Richmond, Virginia 23220 Effective Date February 4, 2021 Job Reference Number 21-126 JP www.bowennational.com 155 E. Columbus Street, Suite 220 | Pickerington, Ohio 43147 | (614) 833-9300 Market Study Certification NCHMA Certification This certifies that Sidney McCrary, an employee of Bowen National Research, personally made an inspection of the area including competing properties and the proposed site in Richmond, Virginia. Further, the information contained in this report is true and accurate as of February 4, 2021. Bowen National Research is a disinterested third party without any current or future financial interest in the project under consideration. We have received a fee for the preparation of the market study. However, no contingency fees exist between our firm and the client. Virginia Housing Certification I affirm the following: 1. I have made a physical inspection of the site and market area 2. The appropriate information has been used in the comprehensive evaluation of the need and demand for the proposed rental units. 3. To the best of my knowledge the market can support the demand shown in this study. I understand that any misrepresentation in this statement may result in the denial of participation in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program in Virginia as administered by Virginia Housing. 4. Neither I nor anyone at my firm has any interest in the proposed development or a relationship with the ownership entity. -

Crossing the River Author: Caryl Phillips

WHS Book Rationale Title: Crossing the River Author: Caryl Phillips ● Intended Audience College Preparatory English 12 ● Brief summary and educational significance Crossing the River begins in the 1700’s as an African man is forced to sell his three children - Nash, Martha and Travis - into slavery. The novel then assumes a three part structure - a snapshot in time during the 1820s, the latter part of the 19th century, and finally the late 1930s-early 1940s. The three children from the beginning are symbolically represented throughout the novel with each of their voices distinct and individual as the reader follows the history of blacks from Africa, to the American West, and to Europe. A slave named Nash Williams is freed from bondage and sent to Liberia to convert native Africans to Christianity in the late-1820s. Narrated partly through Nash’s letters back to his white master, the reader gains an appreciation of not only the brutality and desolation of slavery, but the power of freedom even when it means living in poverty. Martha, an elderly black woman, is abandoned in Colorado while trying to travel with a group of black Pioneers to California. She grieves her lost child, and remembers the love of a man. Finally, Travis - a black American GI - falls in love with a white English woman named Joyce during WWII. This section is narrated in a non-linear fashion from Joyce’s point of view and exposes the bigotry and obstacles to mixed marriage and relationships during that time in history. The novel’s plot is complex because it is non-linear, and is told through multiple genres (letters, journals and a diary, the log of a slave ship). -

Shockoe Bottom Memorialization Community and Economic Impacts

SHOCKOE BOTTOM MEMORIALIZATION COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OCTOBER 2019 SHOCKOE BOTTOM MEMORIALIZATION COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS Prepared for: PRESERVATION VIRGINIA SACRED GROUND HISTORICAL RECLAMATION PROJECT NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Prepared by: CENTER FOR URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS Prepared at: OCTOBER 2019 921 W. Franklin Street • PO Box 842028 • Richmond, Virginia 23284-2028 (804) 828-2274 • www.cura.vcu.edu ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to Elizabeth Kostelny, Justin Sarafin and Lisa Bergstrom of Preservation Virginia for their leader- ship and support throughout this project. We thank Ana Edwards from the Sacred Ground Historic Reclamation Project and Robert Newman from the National Trust for Historic Preservation for sharing their knowledge with us and providing invaluable insights and feedback. We thank Ana also for many of the images of the Shockoe Bottom area used in this report. We also thank Esra Calvert of the Virginia Tourism Corporation for her assistance in obtaining and local tourism visitation and spending data. And we thank the site/museum directors and repre- sentatives from all case studies for sharing their experiences with us. We are also very grateful to the residents, businesses, community representatives, and city officials who partic- ipated in focus groups, giving their time and insights about this transformative project for the City of Richmond. ABOUT THE WILDER SCHOOL The L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University informs public policy through cutting-edge research and community engagement while preparing students to be tomor- row’s leaders. The Wilder School’s Center for Public Policy conducts research, translates VCU faculty research into policy briefs for state and local leaders, and provides leadership development, education and training for state and local governments, nonprofit organizations and businesses across Virginia and beyond.