Stephen Sewell. Artist Talk/Performance. University of Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Full Blown" Internship Program to Begin Professor for President Intel

c c Volume 10, Number 8 College at Lincoln Center, Fordham University, New York December 9, 1987 "Full Blown" Internship Program Intel campus Issues: Student To Begin Affairs Co-Op Loses Government Funding By Mary Kay Linge The Curriculum Committee of the College The demise of CLC's Cooperative Education Council meets this week to begin discussions on (Co-Op) Program, a result of budget cuts in the the form that the program will take, Stratford U.S. Department of Education, may give rise to said. Unlike the Co-Op Program, which match- an all-new internship program "that will make ed students with paid part-time positions in the a connection between the world of academics and field of their choice, "We're going to try to set the world of work," according to Career Plan- up a system of formalized internships" by the ning and Placement Director Bernie Stratford. fall of 1988, said Stratford. "The emphasis won't be on pay.'' Instead, students will probably work several hours a week, then meet together to earn classroom credit, he said —a system similar to the one used at the Rose Hill campus. The Co-Op Program, which had been operating for two years on a combination of federal and University funds, was ended this semester for a single reason: "purely Reaganomics," according to Adult Student Ser- vices Director Ully Hirsch, the administrator who had been responsible for obtaining the federal grant. Hirsch explained that, in order for the govern- ment to choose which schools among the 319 ap- NORMAND PARKNTF.AU plicants should receive funding, each one*had to submit a rigidly outlined proposal. -

Cafo) Expansion and County Board Politics in Rural Illinois

ABSTRACT LINKAGES BETWEEN CONCENTRATED ANIMAL FEEDING OPERATION (CAFO) EXPANSION AND COUNTY BOARD POLITICS IN RURAL ILLINOIS Eric A. Sterling, MA Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2015 Kendall Thu, Advisor Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) are rapidly expanding in rural Illinois. This research explores the political power linkages between county boards and corporate entities in four Illinois counties. The hypothesis is that collusion and impropriety within county board politics and CAFO expansion in rural Illinois are attributed to stakeholder influence and power at the local county government level. My research revealed a connection between ownership of CAFOs, county board political power, and endorsement of expansion. Utilizing Walter Goldschmidt’s method of a controlled comparison, the research analyzes two CAFO inundated counties (Pike and Adams) with two less affected counties (LaSalle and Peoria). Considering the political nature of the research, data collection was forced into engaging secondary text sources to study up, down, and sideways on local government officials. The documents analyzed were public information meeting transcripts, county board meeting transcripts, municipal meeting transcripts, plat maps, public websites, and Freedom of Information Act requests (FOIAs). FOIAs were obtained through government entities and other confidential sources. Citizens are distressed by the proliferation of CAFOs. Through interviews, participant observation, field notes, and archival work, the research indicates that people have knowledge that social stratification is much greater in counties with CAFO proliferation. Citizens that have CAFOs built in close proximity to their property are angered by the permitting system. Considering the amount of pollution and social degradation connected to rapid expansion from livestock farming in Illinois, this research on the linkages between corporate agribusiness and county board politics fills a gap previously overlooked by anthropologists. -

RSD List 2020

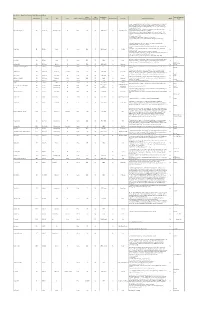

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

'On His Excellent Sophomore Solo Album, Stinson Sings Poignant

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM INDIE SCENE TOMMY STINSON One Man Mutiny tommystinson.com Long before his current stint in Guns N’ Roses, bassist Tommy Stinson served his apprenticeship with the Replacements— simultaneously the Beatles and Rolling Stones of the ’80s alt-rock underground. The Minneapolis group could Tommy Stinson be sharp and melodic, like a punky Fab Four, but also shambolic and self-destructive—particularly onstage, after a few drinks. With the acoustic “Come to Hide,” Stinson steals back from Fortunately, Stinson seems to have soaked up more than just the Goo Goo Dolls the type of heart-on-flannel-sleeve ballad his alcohol during his time in the band. On his excellent sophomore old band invented and perfected. If the similarly ’90s-style “Meant solo album, Stinson makes like former bandmate Paul Westerberg, to Be” and “All This Way for Nothing” suggest the Goos or Cracker singing poignant songs for the emotionally wounded. “Maybe at their absolute best, Stinson proves his versatility with a series of you could use a GPS without all the stop signs,” he suggests on killer change-ups. Among the finest is the country weeper “Zero to “Seize the Moment,” a pro-loser anthem that might have fit on the Stupid,” whose title refers to the mental regression brought about Replacements’ 1985 masterpiece Tim. by “just one drink.” Sung like a true Replacement. ‘On his excellent sophomore solo album, Stinson sings poignant songs for the emotionally wounded.’ SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 M MUSIC & MUSICIANS MAGAZINE. -

The // Skyway \\ the Replacements Mailing List

the // skyway \\ the replacements mailing list issue #100 (november 24, 2016) info: www.theskyway.com www.facebook.com/thematsskyway send your submissions to [email protected] subscription info: you can send an email saying “subscribe skyway” (and hello) to [email protected] COLOR ME IMPRESSED 24 years later, issue #100. I'd say thank you for reading, but really I say thank you for writing. In the end, I have just collected and saved what everybody else has to say about the Replacements. I started because I wanted to hear what everyone else had to say and what memories they had of that band that I loved, from everywhere. So for this 100th issue, I asked 1024 Replacements fans all the questions you´d ask if you met for ten minutes and talked about their favorite band. People who hear the Replacements and just hear the sound of a loose, raucous bar band don't get why this group and its songs are held in such reverence in such a unique way. No matter which album you listen to, there is the spirit, the great songs, the guitar anthems, the colorful personalities, the legend itself of the band that could simultaneously be brilliant and a shambles and whose songs could make you simultaneously laugh and cry. The Replacements are a great story in how they failed at whatever hopes for mainstream success they pursued in a self- sabotaging way, only to reunite two decades later for a little over 30 shows only to become larger than ever and finally achieve the national acclaim they never had. -

Irreplaceable Though Many Have Tried to Copy Them, There’S No Substitute for the Replacements

plalaylisylist BACKLIGHT Irreplaceable Though Many Have Tried to Copy Them, There’s No Substitute for the Replacements By Missy Roback and John Schacht HOW DID THE REPLACEMENTS ever make it out of their Minneapolis garage? Four lovable losers, not a high-school diploma among them, they drank like there was no tomor- row and sabotaged every chance at success that came their way. Got a gig on Saturday Night Live? Hey, Takin’ a Ride Left to right: Chris Mars, Bob Stinson, Paul Westerberg, and Tommy Stinson. let’s drink—a lot! Sold-out show? Let’s play nothing but cheesy Where to Start covers—uh, at least the parts we How old am I?/Let’s count the rings around my eyes” but also wrench poignancy from There’s a reason why the Replacements heavily remember. More comfortable with almost any subject. And he could open a influenced so many bands, from the Goo Goo failure than with success, the ’Mats vein about teenage suicide, alcoholism, love, Dolls to Nirvana. If you’ve never heard the real excelled at putting on notoriously and suburban life—and sound like he was thing, start with these ten tracks. inconsistent gigs, swerving between talking about you. transcendent and terrible from show Because Bob Stinson could wear a dress—or “SHIFTLESS WHEN IDLE” (Sorry Ma, Forgot to show and sometimes from song nothing at all, if the spirits moved him—as no to Take Out the Trash, 1981): The high point of the to song. The band’s most widely other lumbering goofball guitarist could, ’Mats’ abrasive debut, and proof that the young known live recording? It’s called while laying down the big, sloppy riffs that band (bassist Tommy Stinson was a tender 12) anchored the early ’Mats shows. -

March 25 April 1

MARCH 25 ISSUE APRIL 1 Orders Due February 26 7 Orders Due March 4 axis.wmg.com 3/25/16 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Birdy Beautiful Lies ATL CD 825646482061 554263 13.99 2/26/16 Graham, Lukas Lukas Graham WB CD 093624921806 553552 13.99 2/26/16 Hardy, Françoise Et si je m'en vais avant toi (Vinyl) PRH A 190295993511 59935 21.98 2/26/16 Hardy, Françoise La question (Vinyl) PRH A 190295993481 406415 21.98 2/26/16 John Hurt, Kenneth Branagh, Diana Rigg, Joseph Fiennes, Imelda When Love Speaks (Shakespears's Staunton, Alan Rickman, PRX CD 724355732125 557321 12.98 2/26/16 Sonnets) Barbara Bonney, Bryan Ferry, Annie Lennox, Rufus Wainright, etc. Last Update: 04/04/14 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Birdy TITLE: Beautiful Lies Label: TLA/Trill Entertainment, LLC Config & Selection #: CD 554263 Street Date: 03/25/16 Order Due Date: 02/26/16 UPC: 825646482061 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $13.99 Alphabetize Under: B TRACKS Compact Disc 1 01 Growing Pains 08 Lifted 02 Shadow 09 Take My Heart 03 Keeping Your Head Up 10 Hear You Calling 04 Deep End 11 Words 05 Wild Horses 12 Save Yourself 06 Lost It All 13 Unbroken 07 Silhouette 14 Beautiful Lies ALBUM FACTS Genre: Pop ARTIST & INFO Hometown: Lymington, Hampshire, UK Since emerging onto the scene just two years ago, 17-year old Birdy (born Jasmine van den Bogaerde) has catapulted herself into a realm of pop stardom across the world and picked up many accolades along the way. -

500 Songs That Shaped Rock

500 Songs That Shaped Rock James Henke, chief curator for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, with the help of music writers and critics, selected 500 songs (not only rock songs) that they belie e ha e been most influential in shaping rock and roll! "he list is alphabetical by artist! A AC/DC, #$ack in $lack% AC/DC, #Highway to Hell% Roy Acuff and the Smoky Mountain Boys, #&abash 'annonball% Aerosmith, #(ream )n% Aerosmith, #"oys in the *ttic% Afrika Bambaataa, #+lanet Rock% The Allman Brothers Band, #Ramblin, -an% The Allman Brothers Band, #&hipping +ost% The Animals, #"he House of the Rising .un% The Animals, #&e /otta /et )ut of "his +lace% Louis Armstrong, #&est 0nd $lues% Arrested De elo!ment, #"ennessee% B The B"#$%s, #Rock 1obster% 1 of 19 The B-#$%s La&ern Baker, #Jim (andy% 'ank Ballard and the Midnighters, #&ork &ith -e *nnie% The Band, #"he 2ight "hey (ro e )ld (i3ie (own% The Band, #"he &eight% Beach Boys, #'alifornia /irls% Beach Boys, #(on,t &orry $aby% Beach Boys, #/od )nly 4nows% Beach Boys, #/ood 5ibrations% Beach Boys, #.urfin, 6!.!*!% The Beastie Boys, #(7ou /otta) Fight for 7our Right (to +arty)% The Beatles, #* (ay in the 1ife% The Beatles, #Help8% The Beatles, #Hey Jude% The Beatles, #9 &ant to Hold 7our Hand% The Beatles, #2orwegian &ood% The Beatles, #.trawberry Fields Fore er% The Beatles, #7esterday% The Beau Brummels, #1augh 1augh% Beck, #1oser% (eff Beck )rou!, #+lynth (&ater (own the (rain)% The Bee )ees, #.tayin, *li e% Archie Bell and the Drells, #"ighten 6p% Chuck Berry, #Johnny $! /oode% 2 of 19 Chuck Berry, #-aybelline% Chuck Berry, #Rock and Roll -usic% The Big Bo!!er, #'hantilly 1ace% Big Brother and the 'olding Com!any, #+iece of -y Heart% Big Star, #.eptember /urls% Black Sabbath, #9ron -an% Black Sabbath, #+aranoid% Bobby Blue Bland, #"urn )n 7our 1o e 1ight% Blondie, #Heart of /lass% *urtis Blo+, #"he $reaks% )ary ,-S- Bonds, #:uarter to "hree% Booker T- . -

Formal Charges Brought Against Brown • by Garry George with Trabant out of Town Be Reached for Comment

Formal charges brought against Brown • by Garry George With Trabant out of town be reached for comment. the college upon its formation Executive Editor this week, no one in the ad ·Contacted at home, yester in 1976 and retained the post All parties concerned with ministration is willing to com day morning, Brown would not until he was appointed vice the ousting of ex-Vice Presi ment on formal charges that comment on the substance of president in 1978. Brown said, dent for personnel and have now been filed against the charges filed against him however, that he has no desire employee relations Dr. C. Brown. · The case is to be by the university, but was will to return to the position--"! on Harold Brown remain reviewed in an upcoming ing to talk about his position ly want to teach." tight-lipped. Faculty Senate hearing. with the university as he sees According to the universi All but Brown that is. The hearing will determine it. ty's faculty handbook, a Last month, university Brown's position with the Brown said that he has not tenured faculty member can, President E. A. Trabant an university and would ordinari resigned, as the university only be dismissed: claimed last month, and that nounced that Brown had ly make a recommendation to •for three reasons-- "tendered his resignation, ef the vice president for person ·he has no plans to do so in the incompetency, gross fective immediately . for nel and employee relations of future. negligence or moral turpitude. personal reasons" and a board fice. -

Extant Sites ‐ Properties Associated with Minneapolis Music

Extant Sites ‐ Properties Associated with Minneapolis Music Building Date Dates Used for Information Obtained Names Project Address Street Type Genres Extant | Demolished Still Music Related Current Use Notes from Various Sources Mapped Construction date Demolished Music From Originally located at 809 Aldrich Ave N, but that building was demolished in 1970 with I‐94 construction; new building at current location built. Place where Prince's parents, John Nelson and Mattie Shaw met while playing a concert. • 1301 10th Avenue North; Original house at 809 Aldrich Ave N • Started a new annual festival to replace the northside presence at the Aquatennial Phyllis Wheatley Center 1301 10th Ave N Community Center All Extant 1970 NA 1970‐Current Yes Community Center Parade which was contentious after the 1967 incident Yes o Northside Summer Fun Festival drew 6,000 people in its 6th year on August 9, 1978; performers included Sounds of Blackness, Flyte Tyme, Mind & Matter, Quiet Storm, and Prince o Prince also played in 1980 • Hosted Battle of the Bands concerts (no cash prize, just honor) • Original building built in 1924 as a settlement house; http://phylliswheatley.org/ Research • Music Notes Mural: Prince has famous picture in front of it from 1977 by Robert Whitman (book Prince Pre‐fame) 94 S 10th Street o http://www.hungertv.com/feature/the‐photographer‐behind‐princes‐first‐ever‐photo‐ shoot/ Music Notes 88 10th St S Mural All Extant 1908 NA 1971‐Current No The CPG o Painted in 1972 by owners of Schmidt Music (1908); Tom Schmitt great grandson of Yes company’s founder o Van Cliburn, one of world’s finest pianists, did photo session there http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2014/03/30/finding‐minnesota‐the‐mystery‐musical‐mural/ o Featured in Time Magazine piece with Wendell Anderson o The notes are the third movement “Scarbo” in the piece “Gaspard de la Nuit” Research luxury hotel in 1926. -

The Recording and Resurrection of by Bob Mehr the Replacements’ Don’T Tell a Soul

THE RECORDING AND RESURRECTION OF BY BOB MEHR THE REPLACEMENTS’ DON’T TELL A SOUL By the time we made that record, the band had been around for almost ten years. Everything had changed. It seemed like we had two choices. One was to be punks Berg was at Bearsville Studios in Upstate New York, working on Sexton’s album, when Michael Hill on our way out the door . the other was to follow suit and get a hard rock sound—which we really weren’t about. The truth was, we liked pop music: catchy melodies, called. Although Berg technically had no production credits—the Broken Homes record had yet to be released—“Tony was very erudite about music,” said Hill. Berg and Westerberg talked on the phone, and and simple songs. But to write real pop music in that era, you were dead. You were makin’ dead man’s pop.” —Paul Westerberg Paul suggested he send a postcard listing his ten favorite records. “I wrote, ‘These records mean a lot to me; I hope you respond to them,’ ” recalled Berg. “I added, ‘But if you don’t, you can go fuck yourself.’ I got DECEMBER 7, 1987: PORTLAND, OREGON impress—first, it was the guys in the band, then the small army of critics who championed his work. By a call immediately—Paul said to come to New York and meet.” the time Westerberg was in the major-label spotlight, he admitted, “I might have gotten to the point where The skinny, sharp-boned, unmistakable figure of Paul Westerberg is swinging from a crystal chandelier most of my songs were written for beer-swilling 19-year-old males.” Westerberg took an instant shine to Berg, in part, he would later admit, because Berg looked good: He was backstage at the Pine Street Theatre. -

The Ways of the Poem..Pdf

63-07910 821*08 M643w $32!? e'^ Miles, Josephine , 1911- The ways of the poem, Sngle- wood Cliffs, N.J.. PrenticP^ 8a .08 Hiles, Josephine, ^, The ways of the poem. CUffs, N.J., Prentice- ties) literature se f edited by Josephine Miles PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH * UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA N. Englewood Cliffs, J. Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1961 1961 PRENTICE-HALL, INC. ENGLEWOOD CLIFFS, N, J, This volume, with minor revisions, is a shorter version of The Poem by Josephine Miles 1959 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM, BY MIMEO GRAPH OR ANY OTHER MEANS, WITHOUT PER MISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHERS. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD No.: 61-13262 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 94630- C f^. To like a poem is often to want to talk about it, to learn more about it, to hear it over and think about what is heard. This book begins with the ways and terms of such hearing. Then it proceeds to an abundance of poems of all kinds, com posed from different points of view by a hundred poets of four centuries in England and America. Finally, it considers poets as well as poems and poetry, with the work of five poets in some ways wholly individual and in some ways representative of historical changes in thought and tone. This volume is a shorter version of The Poem by about 100 pages of poetry, but contains the work of as many poets, over as wide a range of type and time, as does the fuller form.