Attention, Please Abbey Marie Numedahl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

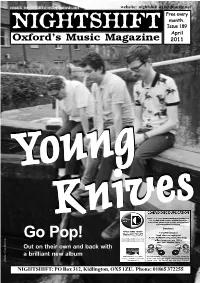

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

C Rossing the P on D

8 [ URBANITE Thursday J December i l * 2003 Crossing the Pond American bands make it overseas but don’t leave a dent in their home country LEILA REGAN___________ “U.K. taste is a lot more Both Associate Urbanite Editor diverse,” says long-time Hiss Bluett and l regan @gsusignal. com promoter and friend and Atlanta Harren appre- Handpicked by quintuple hipster DJ, Dennis Millay, ciated the platinum selling Brit-pop heroes “They care a lot more about “bonus” of Oasis. Exalted by England’s their music. Music is so dispos- having one of most popular music magazine, able here.” the most the National Music Express Swaminathan echoes these influential (NME). Produced by renowned sentiments. men in Brit-pop producer Owen “The U.K. celebrates all England rav- Morris. Seen by thousands at sorts of music,” he said. A ing about the popular English music festivals British citizen’s collection band they in cities such as Leeds and could include the Strokes, represented. Redding. Signed to major Radiohead and Britney Spears. Skipping all British label Polydor’s new sub Here, a Strokes fan would not the grief of sidiary, Loog, which is operated listen to Britney Spears. Brits dealing with by Andrew Loog Oldham (the are a lot more accepting.” middlemen Rolling Stones' original manag “The U.K. is notoriously certainly er and producer). more open to different sounds helped the In spite of all the attention and styles of music,” said 99X Hiss to in the UK, the Hiss still remains music director and ex-manager achieve suc- Special I Signal as they always have been: a of the Hiss, Jay Harren. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

Recensiones. Starmarket, Teenage Fanclub, Hellsongs Y Santi Campos

RECENSIONES. STARMARKET, TEENAGE FANCLUB, HELLSONGS Y SANTI CAMPOS. © Amador Pérez de Algaba de la Torre. Analista Musical Independiente de Sevilla. España. [email protected] PÉREZ DE ALGABA DE LA TORRE, Amador. (2014). “Recensiones. Starmarket, Teenage Fanclub, Hellsongs y Santi Campos”. Montilla (Córdoba): Revista-fanzine Procedimentum nº 3. Páginas 169-176. 1. Starmarket y su disco “Four Hours Light” (Bcore, 2011). Normalmente las reediciones de discos buscan un interés más comercial que artístico. Intenta hacer beneficios a base de sacar brillo a viejas grabaciones que apelan a la nostalgia del oyente, influenciado por algún acontecimiento que hace que el nombre, del artista en cuestión, vuelva a sonar. Nada más lejos de esto ha sido la intención del sello Bcore, quien acaba de reeditar el fabuloso álbum “Four Hours Light” de la banda sueca Starmarker. Con el arrojo y buen gusto de siempre, el sello barcelonés reedita esta completísima obra que vio la luz por primera vez de la mano de sello norteamericano Deep Elm, en 2000. Disco completo tanto por el contenido como por el formato. Con el soporte de un lp de vinilo blanco de doce pulgadas que incluye bono con código para descarga digital, Bcore nos regala uno de esos grandes discos que nunca pasan de moda y que, gracias a su reedición, hace que muchos amantes de la música popular podamos conocer estas doce canciones llenas de fuerza y ternura a las que se etiqueta como emo. Y es que es emoción lo que produce la escucha de canciones plenas que enganchan desde el primer instante. Herencia del mejor rock and roll que recoge esta banda de Estocolmo en la que todo encaja y cada cual cumple su cometido a la perfección, lo que no es extraño si tenemos en cuenta que los países nórdicos son uno de los mejores escenarios musicales de todos los tiempos, que ya desde la tradición jazz se ganaron un puesto principal en la escena mundial. -

Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema Benjamin Speed

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2012 Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema Benjamin Speed Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Speed, Benjamin, "Opera Enormous: Arias in the Cinema" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1749. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/1749 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. OPERA ENORMOUS: ARIAS IN THE CINEMA By Benjamin Speed B. A. , The Evergreen State College, 2002 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Communication) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2012 Advisory Committee: Nathan Stormer, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism, Advisor Laura Lindenfeld, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center Michael Socolow, Associate Professor of Communication and Journalism THESIS ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Benjamin Jon Speed I affirm that this manuscript is the final and accepted thesis. Signatures of all committee members are on file with the Graduate School at the University of Maine, 42 Stodder -

The Search for the "Manchurian Candidate" the Cia and Mind Control

THE SEARCH FOR THE "MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE" THE CIA AND MIND CONTROL John Marks Allen Lane Allen Lane Penguin Books Ltd 17 Grosvenor Gardens London SW1 OBD First published in the U.S.A. by Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., and simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 1979 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 1979 Copyright <£> John Marks, 1979 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner ISBN 07139 12790 jj Printed in Great Britain by f Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland J For Barbara and Daniel AUTHOR'S NOTE This book has grown out of the 16,000 pages of documents that the CIA released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. Without these documents, the best investigative reporting in the world could not have produced a book, and the secrets of CIA mind-control work would have remained buried forever, as the men who knew them had always intended. From the documentary base, I was able to expand my knowledge through interviews and readings in the behavioral sciences. Neverthe- less, the final result is not the whole story of the CIA's attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA's destruction in 1973 of many of the key docu- ments. -

Mhgap Training Manuals

Mental Health Gap Action Programme mhGAP training manuals for the mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings – version 2.0 (for field testing) Mental Health Gap Action Programme mhGAP Training Manuals for the mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings – version 2.0 (for field testing) WHO/MSD/MER/17.6 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specic organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Cafo) Expansion and County Board Politics in Rural Illinois

ABSTRACT LINKAGES BETWEEN CONCENTRATED ANIMAL FEEDING OPERATION (CAFO) EXPANSION AND COUNTY BOARD POLITICS IN RURAL ILLINOIS Eric A. Sterling, MA Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2015 Kendall Thu, Advisor Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) are rapidly expanding in rural Illinois. This research explores the political power linkages between county boards and corporate entities in four Illinois counties. The hypothesis is that collusion and impropriety within county board politics and CAFO expansion in rural Illinois are attributed to stakeholder influence and power at the local county government level. My research revealed a connection between ownership of CAFOs, county board political power, and endorsement of expansion. Utilizing Walter Goldschmidt’s method of a controlled comparison, the research analyzes two CAFO inundated counties (Pike and Adams) with two less affected counties (LaSalle and Peoria). Considering the political nature of the research, data collection was forced into engaging secondary text sources to study up, down, and sideways on local government officials. The documents analyzed were public information meeting transcripts, county board meeting transcripts, municipal meeting transcripts, plat maps, public websites, and Freedom of Information Act requests (FOIAs). FOIAs were obtained through government entities and other confidential sources. Citizens are distressed by the proliferation of CAFOs. Through interviews, participant observation, field notes, and archival work, the research indicates that people have knowledge that social stratification is much greater in counties with CAFO proliferation. Citizens that have CAFOs built in close proximity to their property are angered by the permitting system. Considering the amount of pollution and social degradation connected to rapid expansion from livestock farming in Illinois, this research on the linkages between corporate agribusiness and county board politics fills a gap previously overlooked by anthropologists.