Exploring the Planets Teaching Poster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARS SCIENCE LABORATORY ORBIT DETERMINATION Gerhard L. Kruizinga(1)

MARS SCIENCE LABORATORY ORBIT DETERMINATION Gerhard L. Kruizinga(1), Eric D. Gustafson(2), Paul F. Thompson(3), David C. Jefferson(4), Tomas J. Martin-Mur(5), Neil A. Mottinger(6), Frederic J. Pelletier(7), and Mark S. Ryne(8) (1-8)Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, California 91109, +1-818-354-7060, fGerhard.L.Kruizinga, edg, Paul.F.Thompson, David.C.Jefferson, tmur, Neil.A.Mottinger, Fred.Pelletier, [email protected] Abstract: This paper describes the orbit determination process, results and filter strategies used by the Mars Science Laboratory Navigation Team during cruise from Earth to Mars. The new atmospheric entry guidance system resulted in an orbit determination paradigm shift during final approach when compared to previous Mars lander missions. The evolving orbit determination filter strategies during cruise are presented. Furthermore, results of calibration activities of dynamical models are presented. The atmospheric entry interface trajectory knowledge was significantly better than the original requirements, which enabled the very precise landing in Gale Crater. Keywords: Mars Science Laboratory, Curiosity, Mars, Navigation, Orbit Determination 1. Introduction On August 6, 2012, the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) and the Curiosity rover successful performed a precision landing in Gale Crater on Mars. A crucial part of the success was orbit determination (OD) during the cruise from Earth to Mars. The OD process involves determining the spacecraft state, predicting the future trajectory and characterizing the uncertainty associated with the predicted trajectory. This paper describes the orbit determination process, results, and unique challenges during the final approach phase. -

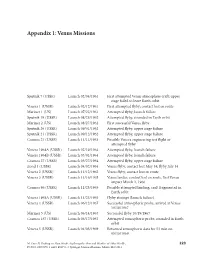

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Five Aerojet Boosters Set to Lift New Horizons Spacecraft

January 15, 2006 Five Aerojet Boosters Set to Lift New Horizons Spacecraft Aerojet Propulsion Will Support Both Launch Vehicle and Spacecraft for Mission to Pluto SACRAMENTO, Calif., Jan. 15 /PRNewswire/ -- Aerojet, a GenCorp Inc. (NYSE: GY) company, will provide five solid rocket boosters for the launch vehicle and a propulsion system for the spacecraft when a Lockheed Martin Atlas® V launches the Pluto New Horizons spacecraft January 17 from Cape Canaveral, AFB. The launch window opens at 1:24 p.m. EST on January 17 and extends through February 14. The New Horizons mission, dubbed by NASA as the "first mission to the last planet," will study Pluto and its moon, Charon, in detail during a five-month- long flyby encounter. Pluto is the solar system's most distant planet, averaging 3.6 billion miles from the sun. Aerojet's solid rocket boosters (SRBs), each 67-feet long and providing an average of 250,000 pounds of thrust, will provide the necessary added thrust for the New Horizons mission. The SRBs have flown in previous vehicle configurations using two and three boosters; this is the first flight utilizing the five boosters. Additionally, 12 Aerojet monopropellant (hydrazine) thrusters on the Atlas V Centaur upper stage will provide roll, pitch, and yaw control settling burns for the launch vehicle main engines. Aerojet also supplies 8 retro rockets for Atlas Centaur separation. Aerojet also provided the spacecraft propulsion system, comprised of a propellant tank, 16 thrusters and various other components, which will control pointing and navigation for the spacecraft on its journey and during encounters with Pluto- Charon and, as part of a possible extended mission, to more distant, smaller objects in the Kuiper Belt. -

ROVING ACROSS MARS: SEARCHING for EVIDENCE of FORMER HABITABLE ENVIRONMENTS Michael H

PERSPECTIVE ROVING ACROSS MARS: SEARCHING FOR EVIDENCE OF FORMER HABITABLE ENVIRONMENTS Michael H. Carr* My love affair with Mars started in the late 1960s when I was appointed a member of the Mariner 9 and Viking Orbiter imaging teams. The global surveys of these two missions revealed a geological wonderland in which many of the geological processes that operate here on Earth operate also on Mars, but on a grander scale. I was subsequently involved in almost every Mars mission, both US and non- US, through the early 2000s, and wrote several books on Mars, most recently The Surface of Mars (Carr 2006). I also participated extensively in NASA’s long-range strategic planning for Mars exploration, including assessment of the merits of various techniques, such as penetrators, Mars rovers showing their evolution from 1996 to the present day. FIGURE 1 balloons, airplanes, and rovers. I am, therefore, following the results In the foreground is the tethered rover, Sojourner, launched in 1996. On the left is a model of the rovers Spirit and Opportunity, launched in 2004. from Curiosity with considerable interest. On the right is Curiosity, launched in 2011. IMAGE CREDIT: NASA/JPL-CALTECH The six papers in this issue outline some of the fi ndings of the Mars rover Curiosity, which has spent the last two years on the Martian surface looking for evidence of past habitable conditions. It is not the fi rst rover to explore Mars, but it is by far the most capable (FIG. 1). modest-sized landed vehicles. Advances in guidance enabled landing Included on the vehicle are a number of cameras, an alpha particle at more interesting and promising places, and advances in robotics led X-ray spectrometer (APXS) for contact elemental composition, a spec- to vehicles with more independent capabilities. -

+ New Horizons

Media Contacts NASA Headquarters Policy/Program Management Dwayne Brown New Horizons Nuclear Safety (202) 358-1726 [email protected] The Johns Hopkins University Mission Management Applied Physics Laboratory Spacecraft Operations Michael Buckley (240) 228-7536 or (443) 778-7536 [email protected] Southwest Research Institute Principal Investigator Institution Maria Martinez (210) 522-3305 [email protected] NASA Kennedy Space Center Launch Operations George Diller (321) 867-2468 [email protected] Lockheed Martin Space Systems Launch Vehicle Julie Andrews (321) 853-1567 [email protected] International Launch Services Launch Vehicle Fran Slimmer (571) 633-7462 [email protected] NEW HORIZONS Table of Contents Media Services Information ................................................................................................ 2 Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................. 3 Pluto at a Glance ...................................................................................................................... 5 Why Pluto and the Kuiper Belt? The Science of New Horizons ............................... 7 NASA’s New Frontiers Program ........................................................................................14 The Spacecraft ........................................................................................................................15 Science Payload ...............................................................................................................16 -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

A Tracer of CO2 Density Variations in the Martian Lower CO2 Density Provided by the Mars Climate Database Is Scaled Down by a Factor Between 0.50 and 0.66

Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 1 RESEARCH ARTICLE The O( S) 297.2-nm Dayglow Emission: A Tracer of CO2 Density 10.1029/2018JE005709 Variations in the Martian Lower Thermosphere Key Points: L. Gkouvelis1 , J.-C. Gérard1 , B. Ritter1,2 , B. Hubert1 , N. M. Schneider3 , and S. K. Jain3 • Limb observations of the O(1S-3P) fi dayglow by MAVEN con rm 1LPAP, STAR Institute, Université de Liège, Liege, Belgium, 2Royal Observatory of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium, 3LASP, existence of previously predicted emission peak near 80 km University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA • We successfully model the lower peak emission profile and show that 1 it only depends on the vertical CO2 Abstract The O( S) metastable atoms can radiatively relax by emitting airglow at 557.7 and 297.2 nm. The distribution and solar Ly-alpha latter one has been observed with the Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph onboard the Mars Atmosphere • Combination of model and fi observations enable to constrain the and Volatile Evolution Mars orbiter since 2014. Limb pro les of the 297.2-nm dayglow have been collected slant CO2 column over the peak and near periapsis with a spatial resolution of 5 km or less. They show a double-peak structure that was previously the corresponding atmospheric predicted but never observed during earlier Mars missions. The production of both 297.2-nm layers is pressure dominated by photodissociation of CO2. Their altitude and brightness is variable with season and latitude, reflecting changes in the total column of CO2 present in the lower thermosphere. Since the lower emission peak near 85 km is solely produced by photodissociation, its peak is an indicator of the unit optical depth Correspondence to: pressure level and the overlying CO2 column density. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

Combinatorics in Space

Combinatorics in Space The Mariner 9 Telemetry System Mariner 9 Mission Launched: May 30, 1971 Arrived: Nov. 14, 1971 Turned Off: Oct. 27, 1972 Mission Objectives: (Mariner 8): Map 70% of Martian surface. (Mariner 9): Study temporal changes in Martian atmosphere and surface features. Live TV A black and white TV camera was used to broadcast “live” pictures of the Martian surface. Each photo-receptor in the camera measures the brightness of a section of the Martian surface about 4-5 km square, and outputs a grayness value in the range 0-63. This value is represented as a binary 6-tuple. The TV image is thus digitalized by the photo-receptor bank and is output as a stream of thousands of binary 6-tuples. Coding Needed Without coding and a failure probability p = 0.05, 26% of the image would be in error ... unacceptably poor quality for the nature of the mission. Any coding will increase the length of the transmitted message. Due to power constraints on board the probe and equipment constraints at the receiving stations on Earth, the coded message could not be much more than 5 times as long as the data. Thus, a 6-tuple of data could be coded as a codeword of about 30 bits in length. Other concerns A second concern involves the coding procedure. Storage of data requires shielding of the storage media – this is dead weight aboard the probe and economics require that there be little dead weight. Coding should therefore be done “on the fly”, without permanent memory requirements. -

A Possible Flyby Anomaly for Juno at Jupiter

A possible flyby anomaly for Juno at Jupiter L. Acedo,∗ P. Piqueras and J. A. Mora˜no Instituto Universitario de Matem´atica Multidisciplinar, Building 8G, 2o Floor, Camino de Vera, Universitat Polit`ecnica de Val`encia, Valencia, Spain December 14, 2017 Abstract In the last decades there have been an increasing interest in im- proving the accuracy of spacecraft navigation and trajectory data. In the course of this plan some anomalies have been found that cannot, in principle, be explained in the context of the most accurate orbital models including all known effects from classical dynamics and general relativity. Of particular interest for its puzzling nature, and the lack of any accepted explanation for the moment, is the flyby anomaly discov- ered in some spacecraft flybys of the Earth over the course of twenty years. This anomaly manifest itself as the impossibility of matching the pre and post-encounter Doppler tracking and ranging data within a single orbit but, on the contrary, a difference of a few mm/s in the asymptotic velocities is required to perform the fitting. Nevertheless, no dedicated missions have been carried out to eluci- arXiv:1711.08893v2 [astro-ph.EP] 13 Dec 2017 date the origin of this phenomenon with the objective either of revising our understanding of gravity or to improve the accuracy of spacecraft Doppler tracking by revealing a conventional origin. With the occasion of the Juno mission arrival at Jupiter and the close flybys of this planet, that are currently been performed, we have developed an orbital model suited to the time window close to the ∗E-mail: [email protected] 1 perijove. -

Seasonal and Interannual Variability of Solar Radiation at Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity Landing Sites

Seasonal and interannual variability of solar radiation at Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity landing sites Álvaro VICENTE-RETORTILLO1, Mark T. LEMMON2, Germán M. MARTÍNEZ3, Francisco VALERO4, Luis VÁZQUEZ5, Mª Luisa MARTÍN6 1Departamento de Física de la Tierra, Astronomía y Astrofísica II, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, [email protected]. 2Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, [email protected]. 3Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, [email protected]. 4Departamento de Física de la Tierra, Astronomía y Astrofísica II, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, [email protected]. 5Departamento de Matemática Aplicada, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, [email protected]. 6Departamento de Matemática Aplicada, Universidad de Valladolid, Segovia, Spain, [email protected]. Received: 14/04/2016 Accepted: 22/09/2016 Abstract In this article we characterize the radiative environment at the landing sites of NASA's Mars Exploration Rover (MER) and Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) missions. We use opacity values obtained at the surface from direct imaging of the Sun and our radiative transfer model COMIMART to analyze the seasonal and interannual variability of the daily irradiation at the MER and MSL landing sites. In addition, we analyze the behavior of the direct and diffuse components of the solar radiation at these landing sites. Key words: Solar radiation; Mars Exploration Rovers; Mars Science Laboratory; opacity, dust; radiative transfer model; Mars exploration. Variabilidad estacional e interanual de la radiación solar en las coordenadas de aterrizaje de Spirit, Opportunity y Curiosity Resumen El presente artículo está dedicado a la caracterización del entorno radiativo en los lugares de aterrizaje de las misiones de la NASA de Mars Exploration Rover (MER) y de Mars Science Laboratory (MSL). -

Planetary Science

Mission Directorate: Science Theme: Planetary Science Theme Overview Planetary Science is a grand human enterprise that seeks to discover the nature and origin of the celestial bodies among which we live, and to explore whether life exists beyond Earth. The scientific imperative for Planetary Science, the quest to understand our origins, is universal. How did we get here? Are we alone? What does the future hold? These overarching questions lead to more focused, fundamental science questions about our solar system: How did the Sun's family of planets, satellites, and minor bodies originate and evolve? What are the characteristics of the solar system that lead to habitable environments? How and where could life begin and evolve in the solar system? What are the characteristics of small bodies and planetary environments and what potential hazards or resources do they hold? To address these science questions, NASA relies on various flight missions, research and analysis (R&A) and technology development. There are seven programs within the Planetary Science Theme: R&A, Lunar Quest, Discovery, New Frontiers, Mars Exploration, Outer Planets, and Technology. R&A supports two operating missions with international partners (Rosetta and Hayabusa), as well as sample curation, data archiving, dissemination and analysis, and Near Earth Object Observations. The Lunar Quest Program consists of small robotic spacecraft missions, Missions of Opportunity, Lunar Science Institute, and R&A. Discovery has two spacecraft in prime mission operations (MESSENGER and Dawn), an instrument operating on an ESA Mars Express mission (ASPERA-3), a mission in its development phase (GRAIL), three Missions of Opportunities (M3, Strofio, and LaRa), and three investigations using re-purposed spacecraft: EPOCh and DIXI hosted on the Deep Impact spacecraft and NExT hosted on the Stardust spacecraft.