The Repellent Mr Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fame Attack : the Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences

Rojek, Chris. "The Icarus Complex." Fame Attack: The Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 142–160. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849661386.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:03 UTC. Copyright © Chris Rojek 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 The Icarus Complex he myth of Icarus is the most powerful Ancient Greek parable of hubris. In a bid to escape exile in Crete, Icarus uses wings made from wax and feathers made by his father, the Athenian master craftsman Daedalus. But the sin of hubris causes him to pay no heed to his father’s warnings. He fl ies too close to the sun, so burning his wings, and falls into the Tsea and drowns. The parable is often used to highlight the perils of pride and the reckless, impulsive behaviour that it fosters. The frontier nature of celebrity culture perpetuates and enlarges narcissistic characteristics in stars and stargazers. Impulsive behaviour and recklessness are commonplace. They fi gure prominently in the entertainment pages and gossip columns of newspapers and magazines, prompting commentators to conjecture about the contagious effects of celebrity culture upon personal health and the social fabric. Do celebrities sometimes get too big for their boots and get involved in social and political issues that are beyond their competence? Can one posit an Icarus complex in some types of celebrity behaviour? This chapter addresses these questions by examining celanthropy and its discontents (notably Madonna’s controversial adoption of two Malawi children); celebrity health advice (Tom Cruise and Scientology); and celebrity pranks (the Sachsgate phone calls involving Russell Brand and Jonathan Ross). -

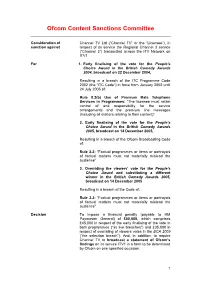

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee Consideration of Channel TV Ltd (“Channel TV” or the “Licensee”), in sanction against respect of its service the Regional Channel 3 service (“Channel 3”) transmitted across the ITV Network on ITV1. For 1. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2004, broadcast on 22 December 2004, Resulting in a breach of the ITC Programme Code 2002 (the “ITC Code”) in force from January 2002 until 24 July 2005 of: Rule 8.2(b) Use of Premium Rate Telephone Services in Programmes: “The licensee must retain control of and responsibility for the service arrangements and the premium line messages (including all matters relating to their content)” 2. Early finalising of the vote for the People’s Choice Award in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005, Resulting in a breach of the Ofcom Broadcasting Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” 3. Overriding the viewers’ vote for the People’s Choice Award and substituting a different winner in the British Comedy Awards 2005, broadcast on 14 December 2005 Resulting in a breach of the Code of: Rule 2.2: “Factual programmes or items or portrayals of factual matters must not materially mislead the audience” Decision To impose a financial penalty (payable to HM Paymaster General) of £80,000, which comprises £45,000 in respect of the early finalising of the vote in both programmes (“as live breaches”) and £35,000 in respect of overriding of viewers votes in the BCA 2005 (“the selection breach”). -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

Samuel Beckett and the Reception of Harold Pinter's Early

“Random dottiness”: Samuel Beckett and the reception of Harold Pinter’s early dramas Book or Report Section Accepted Version Bignell, J. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4874-1601 (2020) “Random dottiness”: Samuel Beckett and the reception of Harold Pinter’s early dramas. In: Rakoczy, A., Hori Tanaka, M. and Johnson, N. (eds.) Influencing Beckett / Beckett Influencing. Collection Karoli. L'Harmattan, Budapest & Paris, pp. 61-74. ISBN 9782343219110 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/95305/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: https://webshop.harmattan.hu/? id=aa725cb0e8674da4a9ddf148c5874cdc&p=termeklap&tkod=4605 Publisher: L'Harmattan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online (Published in: Anita Rákóczy, Mariko Hori Tanaka & Nicholas Johnson, eds. Infleuncing Beckett / Beckett Influencing. Budapest & Paris: L’Harmattan, 2020, pp. 61-74). “Random dottiness”: Samuel Beckett and the reception of Harold Pinter’s early dramas by Jonathan Bignell Abstract This essay analyzes the significance of Samuel Beckett to the British reception of the playwright Harold Pinter’s early work. Pinter’s first professionally produced play was The Birthday Party, performed in London in 1958. Newspaper critics strongly criticized it and its run was immediately cancelled. Beckett played an important role in this story, through the association of Pinter’s name with a Beckett “brand” which was used in reviews of The Birthday Party to sum up what was wrong with Pinter’s play. -

Brits Choose Holiday Partners for Sun, Sand, And… a Laugh Submitted By: Pr-Sending-Enterprises Friday, 15 September 2006

Brits choose holiday partners for sun, sand, and… a laugh Submitted by: pr-sending-enterprises Friday, 15 September 2006 British holidaymakers would pick fun over glamour when it comes to holiday companions according to research by Barclays Insurance (http://www.barclays.co.uk/insurance). Northern comedian Peter Kay has topped the list of celebrities Brits would most like to go on holiday with, relegating homegrown starlet Keira Knightley and Hollywood heart throb George Clooney to second and third places. Elsewhere in the list, Kylie Minogue and Angelina Jolie are the only other non-Brits in a top ten dominated by British personalities. Whilst good looks and the fun factor clearly play an important part when choosing Britain’s favourite holiday companion it seems that most people remain loyal to their local heroes – Scots favoured Sean Connery whilst the North of England was the most supportive of Peter Kay. Unsurprisingly, good-looking and successful members of the opposite sex made up the top ideal holiday companions for both male and female respondents with the exception of all-round favourite Peter Kay who appeared second in the lists for both sexes. However it appears that a large number of male holidaymakers would prefer to take a fellow fella with them on their travels with a total of four males featuring in their top ten whilst the only woman that females would consider holidaying with is Davina McCall. Across the age groups, Big Brother presenter Dermot O’Leary was the most popular companion amongst the under 30s but over 50s would prefer to share a sunlounger with Joanna Lumley. -

Keffiyeh-Clad Heirs of Streicher

VOLUME 2 No. 9 SEPTEMBER 2002 Keffiyeh-clad heirs of Streicher Ihe atrocities of September 11 drew less slaughter gentile children to make matzos '^nan a unanimous reaction from across the for Passover. Cairo, the intellectual capital *orld. The West was divided between a of the entire Muslim cosmos, boasts Ein horror-struck majority and a minority who Shams University. Here Dr Adel Sadeq, deplored the deed but felt they could President of the Arab Psychiatrists 'understand' the perpetrators. The East Association, recently intoned this paean of •displayed a different sort of division. Some praise to suicide bombers: "As a Muslims, exemplified by the ululating professional psychiatrist, I say that the Women caught on camera in the West height of bliss comes with the end of the "3nk, rejoiced, while others professed to countdown: ten, nine, eight, seven, six, "^tect the hand of the Israeli intelligence September 11 Ground Zero five, four, three, two, one. When the service Mossad behind the atrocity. As martyr reaches 'one' and he explodes, he June 28. The article, permed by ex-editor P''oof, they cited the Saudi-manufactured has a sense of himself flying, because he Harold Evans, talked of a "dehumanisation °^ega-lie that 4,000 Jewish employees of knows for certain that he is not dead. It is a of all Jews manufactured and propagated the World Trade Center were absent from transition to another, more beautiful, throughout the Middle East and south *ork on September 11 because they had world. None in the Western world Asia on a scale and intensity that is utterly •^een tipped off. -

X FACTOR JUDGE CHERYL COLE and KYLIE MINOGUE MOST POWERFUL CELEBRITIES in BRITAIN HIGHLIGHTS RESEARCH Submitted By: Eureka Communications Wednesday, 31 March 2010

X FACTOR JUDGE CHERYL COLE AND KYLIE MINOGUE MOST POWERFUL CELEBRITIES IN BRITAIN HIGHLIGHTS RESEARCH Submitted by: Eureka Communications Wednesday, 31 March 2010 31st March 2010, London, UK – Pop star Kylie Minogue and X-Factor judge Cheryl Cole were named the most powerful celebrities in Britain today in Millward Brown’s latest celebrity and brand (Cebra) research . The research, which interviewed 2000 consumers about 100 celebrities and 100 brands, will be used by marketers to identify celebrity and brand partnerships with the greatest marketplace potential. The 10 most powerful UK celebrities were: 1)Kylie Minogue 2)Cheryl Cole 3)David Beckham 4)Ant & Dec 5)Joanna Lumley 6)Terry Wogan 7)Jamie Oliver 8)George Clooney 9)Sean Connery 10)Helen Mirren “Kylie is widely accepted as an adopted Brit. People know her, like her and she is surrounded by positive buzz,” says Mark Husak, Head of Millward Brown’s UK Media Practice. Cheryl’s mix of exciting, endearing and engaging traits seems to be a winning combination.” Cheryl Cole is 2nd in the ranking and has the highest positive Buzz score (80 percent positive) despite the negative media coverage that has surrounded her in the past. Cheryl is seen as very Playful, Sympathetic and Outgoing but least Reserved, Calm and Laid Back. She is well matched to Coca Cola and New Look. Kylie’s personality matches well with L’Oreal, Yahoo, Cadbury and Lucozade. Research highlights: •US star George Clooney (8th in the ranking) is the only other non-Brit to appear in the Top10. Like Kylie, he is well liked with no negative publicity. -

Brand and the BBC – the Full Expletive-Riddled Truth

Brand and the BBC – the full expletive-riddled truth blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2008/11/05/brand-and-the-bbc-the-full-expletive-riddled-truth/ 2008-11-5 Was it a storm in a tea-cup or a symbol of a wider malaise at the BBC? Well Polis has got the full, expletive-riddled story from a senior BBC figure. Caroline Thomson is the BBC’s Chief Operating Officer, second only in importance at the corporation to her namesake, Mark. In a speech to Polis she gave a lengthy and carolinethomson.jpg candid narrative of the whole Brand/Ross prank phone call saga. In it she makes a staunch defence of the BBC’s actions and calls on the corporation to continue taking risk. But she recognised in her speech, and the subsequent exchange we had, that it does raise a wider question: Is the BBC too keen to do too much instead of focusing on what it does best. Here is her speech which I think is well worth reading in full – it will also go up on the main Polis website. The BBC: The Challenge to Appeal to All Audiences Caroline Thomson, Chief Operating Officer, BBC POLIS Media Leadership Dialogues London School of Economics, Tuesday 4 November What a week – when I agreed to do this talk I thought I would focus on transforming the BBC – getting it to be a networked organisation, representing the whole of the UK with London as its hub, not its dominant force, with our plans for our new base in the Manchester region as the central theme. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Market Impact Assessment of the BBC's High Definition

Market Impact Assessment of the BBC’s High Definition Television Proposals A report of market research conducted for Ofcom by Illuminas Publication date: 18 September 2007 Contents Section Page 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Background and Research Objectives 6 3 Research Methodology 8 4 Profile of current HDTV subscribers 12 5 HDTV and its impact on viewing behaviour 18 6 The Impact of HDTV on other TV-based activities 33 7 Perceptions and usage of the trial BBC HD channel 39 8 The proposed 9 hour BBC HD channel 47 9 The proposed overnight BBC HD channel 58 Section 1 Executive Summary Background, objectives and methodology BBC HD is currently in a trial stage and is being offered over both Virgin Media V+ and Sky HD. It has been decided to apply a Public Value Test (PVT) to the BBC’s proposal to make the trial BBC HD channel permanent. The central objective of this piece of research was to assess the possible impact of the BBC launching an HD channel. The research comprised the following elements: • 400 x 30 minute, in home CAPI interviews with subscribers to HDTV; and • 10 x diary-depth interviews with respondents from the quantitative stage. Adoption, understanding and experience of HDTV The backing of major brands, such as Sky, BBC and Virgin, as well as equipment manufacturers like Sony and Panasonic, appears to have reduced perceived risks of adoption and driven take-up of HD rapidly through the adoption curve. There are still misunderstandings about HDTV. Two fifths (41%) of HDTV subscribers think that HD quality pictures are available on all TV channels rather than just dedicated HD broadcast channels. -

'Radio': the Audio Afterlife of Television

TV on the ‘Radio’: The Audio Afterlife of Television Paul Reinsch, Texas Tech University The flow of television has always included a stream of sounds as well as images. That these sounds anchor the image and hail the audience has been perhaps relatively, though certainly not completely, neglected by media scholars. The audio address of television facilitates, or may even encourage, the “distracted” viewing explored by various scholars. I am especially interested in the official and unofficial audio recordings of television transmissions and how these texts preserve, transform, and mobilize specific content and television as an idea. Unofficial recordings, in particular, indicate a desire to (re)use a text, and also perhaps to create a bulwark against the (perceived) ephemerality of television, whether live, “live,” or even subject to syndication (and so endlessly looping back around). These works uncover the home as an—audio—archive of television (decades before the DVR became as much of a fixture as lamps and rugs). The transformation of an audio-visual television text into an audio text can be linked not only to sound studies but also discussions of paratexts and “paratextual memory.” Official audio adaptations of television and film texts dot the history of media, and DVD and Blu-ray releases make audio versions of works like Stagecoach available for close study. Less studied (if no less readily available) are releases such as the albums (vinyl, cassette, CD, download) for works such as Fawlty Towers (1975, 1979). As early as 1979, two episodes appeared as audio texts on LP as an offering from BBC Radio, though the texts are not radio adaptations but a transfer of audio content. -

The BBC: Past, Present and Future Jonathan Nunns the British Broadcasting Corporation Is a Large, Publicly Owned U.K

1 The BBC: Past, Present and Future Jonathan Nunns The British Broadcasting Corporation is a large, publicly owned U.K. broadcaster with a global reach. 2 The old and new BBC Broadcasting Houses in London. Old Broadcasting House New Broadcasting House ( now demolished ). ( originally the radio centre built 1932 ). Recently massively extended to put TV and Radio under one roof. BBC Salford-The new Northern Hub. Who pays for the BBC and how? 3 We all do. The BBC is funded by a universal licence fee-currently £145.50 per year. If you get TV live off air you are obliged to pay the fee. Currently, If you don’t pay and still watch TV, you could wind up in court. Does the BBC belong to the government? 4 No-it belongs to license fee payers and should be independent of whichever government is in power. It’s content is monitored by OFCOM the main UK Media regulator. How much income does the BBC get and 5 where from? Who Runs The BBC? 6 Tony Hall BBC Director General ( CEO ) Rona Fairhead Chair of the BBC Trust ( governing body- overseeing the BBC ) What has the BBC Ever Done for 7 Us? Such as……….. 8 9 Sport for all? 10 British Film Forever! The Life Scientific? 11 Art for arts sake? 12 Radio Ga Ga? 13 We could go on to include:- 14 Natural History Children’s Television Current Affairs History Drama Comedy Consumer Affairs Documentary and many, many more. So where did it all begin? 15 The Birth of Radio and Television Radio 1922 Television 1936 Who established the BBC and why? 16 John Reith was the first BBC Director General in 1922–introducing the new technology of radio to the UK.