Public Parks and Open Spaces Which Has Not Been Given by Government the Kind of Attention That It Deserves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balikbayan Plus Program Establishment Guide ( May 15, 2017 )

BALIKBAYAN PLUS PROGRAM ESTABLISHMENT GUIDE -+ ( MAY 15, 2017 ) DENTAL CLINIC HOTEL THE SPA CASTILLO-ORTHO DENTAL (Alabang, BGC, Eastwood, APO VIEW HOTEL BEAUTY & WELLNESS CLINIC ( Las Piñas City) (J.Camus St. Davao City) Greenbelt, Promenade, BEAUCHARM DERMA Shangri-la and Trinoma ) - Dr. Jose Castillo * Ms. Jasmin Acuin / FACIAL (Makati City) -Ms. Noemi Pablo-Doce* Ms. Bonadee - Basic Dental Procedures - 25% OFF Ms. Maricar Dimayuga. Ms. Paula - Ms. Cora de Guzman Castro - Orthodontics Treatment - 20% OFF - 20% OFF on hotel rooms - FREE Diamond peel on the -20% OFF on Single The Spa Wellness -Removal and Fixed Prosthesis - 20% -10% OFF on food and beverage OFF cardholder’s Ist visit Service ( on solo visit ) - Until May 31, 2018* +632.935. 6732 - 20% OFF on all major surgical and - 25% OFF on Single The Spa Wellness - Until April 07, 2018* +632.874.5355 +63.943.837.7003 non-surgical treatments Service if visiting with 2 or more companions ( PLUS 5% OFF on ENTERTAINMENT - 10% OFF on hair removal, body scrub, massage and foot treatments companion ) MANILA OCEAN PARK - Until May 31, 2018 *+632.893.0872 * -10% OFF on the New Exclusive (Manila ) ASTORIA GREENBELT +632.579.9610 Membership (Cardholder and - Ms.Mayette Ongsioco / - Ms. Mica Dumayas * companion ) Ms. Nissah Custodio Ms. Marlyn Balete BARRE 3 -Until November 14, 2017 - DISCOUNT on Attraction packages: -Room Accommodations @ 30% - (All Branches except - +632.656.5790 local 202 / 209 a) Corporate SIG -1(Oceanarium, Shark 64% OFF Greenbelt ) & Ray Dry Encounter, Symphony - 10% OFF on F&B -Ms. Noemi Pablo-Doce * SKIN DERMATOLOGY AND Evening Show, Sea Lion Show, Jellies -5% OFF on Social Functions Ms. -

'17 JUL31 All

SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE ) REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) 'W e ' C'ffitf pfliir :r-;-,-;rlnry Second Regular Session ) SENATE '17 JUL 31 All '33 Senate Bill No. 1529 RECE iVI D £':■ (In substitution of Senate Bill Nos. 420, 556, 608, 671, 915, 1081 and 1T74)- Prepared jointly by the Committees on Education, Arts and Culture, Ways and Means and Finance, with Senators Legarda, Binay, Trilianes IV, Aquino IV, Ejercito and Escudero as authors AN ACT STRENGTHENING THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE PHILIPPINES, REPEALING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 8492, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE NATIONAL MUSEUM ACT OF 1998, AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled: 1 SECTION 1. Short Title. - This Act shall be known as the ‘‘National Museum of the 2 Philippines Act”. 3 4 SEC. 2. Declaration of Policy. - It is the policy of the State to pursue and support the cultural 5 development of the Filipino people, through the preservation, enrichment and dynamic evolution of 6 Filipino national culture, based on the principle of unity in diversity in a climate of free artistic and 7 intellectual expression. 8 9 SEC. 3. Name of the Agency. - The National Museum is hereby renamed as the “National 10 Museum of the Philippines”, or, alternatively in Filipino, “Pambansang Museo ng Pilipinas'\ 11 12 The shortened name “National Museum” or “Pambansang Museo" shall be understood as 13 exclusively referring to the same, and its use in any manner or part of any name with respect to any 14 institution within the Philippines shall be reserved exclusively to the same. -

Featured Projects

IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES FEATURED PROJECTS . ADDRESS : B13 L9 Strawberry Rd. Palmera 6 Dolores Taytay Rizal | [email protected] | TELEFAX: (02) 660-3728 | TELEPHONE: (02) 775-1328 | IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION THE MANILA AMERICAN CEMETERY Fort Bonifacio Makati City, Philippines This cemetery is the largest cemetery in the Pacific for US personnel killed during the second world war. It also holds Philippine war dead and other allies killed during the war. Most of those buried here died during the Battle of the Philippines in the first two years of the war. This area is 152 acres, or 615,000 square meters. (1997-1998) · Domestic / NAWASA Water Line & Piping work · Supply of Materials & Installation of Fully Automatic Domestic Pumping System Deepwell Construction & Maintenance ( 10 inches casing, 600 ft. Deep ) · Deepwell Maintenance · Fountain Maintenance · Supply & Installation of Fire Hydrants · Supply & Installation of Fully Automatic AMIAD Filtration System · Design, Supply & Installation of NAWASA ( incoming line ) · Automatic Shut-off Valves & Water Reservoir Float Switch · Sub-soil Drain, Laying of Sand & Re-installation of Automatic Irrigation System · Pipe Laying 8” dia. uPVC pipe between Deepwells & Reservoir ( 600 meters ) · Design, Supply & Installation of Fully Computerized Flowtronex PSI Pumping System · Design, Supply of RAIN BIRD Maxi-Com Computerized Irrigation System ( Complete with Weather Station ) ADDRESS : B13 L9 Strawberry Rd. Palmera 6 Dolores Taytay Rizal | [email protected] | TELEFAX: (02) 660-3728 | TELEPHONE: (02) 775-1328 | IRRIGATION ENTERPRISES MANILA POLO CLUB, INC. Forbes Park, Makati City, Philippines The 25-hectare grounds encompass two polo fields and a whole range of other sporting facilities such as swimming pool, tennis courts, golf driving range, equestrian grounds, gym, squash courts, bowling lanes and badminton courts. -

Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using Pagerank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2

“Transportation for A Better Life: Harnessing Finance for Safety and Equity in AEC August 21, 2015, Bangkok, Thailand Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using PageRank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2 1Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We attempt to identify the different node hubs of a road network using PageRank for preparation for possible random terrorist attacks. The robustness of a road network against such attack is crucial to be studied because it may cripple its connectivity by simply shutting down these hubs. We show the important hubs in a road network based on network structure and propose a model for robustness analysis. By identifying important hubs in a road network, possible preparation schemes may be done earlier to mitigate random terrorist attacks, including defense reinforcement and transportation security. A case study of the Metro Manila road network is also presented. The case study shows that the most important hubs in the Metro Manila road network are near airports, piers, major highways and expressways. Keywords: PageRank, Terrorist Attack, Robustness 1. Introduction Table 1 Comparative analysis of different Roads are important access points because methodologies on network robustness indices connects different places like cities, districts, and Author Method Strength Weakness landmarks. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of November 30, 2019 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 (FMEI) Fernando Medical Enterprises 1460-1462 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Quezon City Maria Victoria F. Gutierrez - Managing (02)727 1521; marivicgutierrez@f Medical/Dental 31-Dec-19 Inc. Immculate Concepcion, Quezon City Director (02)727 1532 ernandomedical.co m 2 08 Auto Services 1 Star 4 B. Serrano cor. William Shaw Street, Caloocan City Edson B. Cachuela - Proprietor (02)330 6907 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 Caloocan City Aircon Servicing) 3 1 Stop Battery Shop, Inc. 1 Star 214 Gen. Luis St., Novaliches, Quezon Quezon City Herminio DC. Castillo - President and (02)9360 2262 419 onestopbattery201 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 City General Manager 2859 [email protected] Aircon Servicing) 4 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star B1 L1 Sheryll Mirra Street, Multinational Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)821 1202 macuzreyes129@ Automotive (Including 31-Dec-19 Village, Parañaque City gmail.com Aircon Servicing) 5 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-19 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 6 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M-Roxas Street, Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Robert C. Quides - Owner (02)954 4704 iluvurobert@gmail. Automotive 31-Dec-19 com (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 7 3BMA Refrigeration & Airconditioning 1 Star 2 Don Pepe St., Sto. -

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

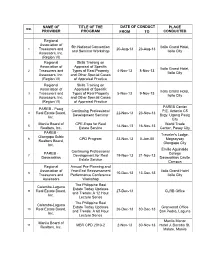

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

Discordant Order: Manila's Neo Patrimonial Urbanism

Peter Murphy Pre-Publication Archive This is a pre-publication article. It is provided for researcher browsing and quick reference. The final published version of the article is available at: ‘Discordant Order: Manila’s Neo Patrimonial Urbanism’, Thesis Eleven: Critical Theory and Historical Sociology 112 (London: Sage, 2012), pp 10-34. 1 Discordant Order: Manila’s Neo Patrimonial Urbanism Peter Murphy and Trevor Hogan Manila is one of the world’s most fragmented, privatized and un-public of cities. Why is this so? This paper contemplates the seemingly immutable privacy of the city of Manila, and the paradoxical character of its publicity. Manila is our prime exemplar of the twenty-first century mega-city whose apparent disorder discloses a coherent order which we here call ‘neo- patrimonial urbanism’. Manila is a city where poor and rich alike have their own government, infrastructure, and armies, the shopping malls are the simulacra of public congregations once found in cathedrals and plazas, and where household order is matched by streetside chaos, and personal cleanliness wars with public dirt. We nominate the key characteristics of this uncanny approximation of chaotic and discordant order – a polyphonous and polyrhythmic social order but one lacking harmony – and offer a historical sociology, a genealogy that traces an emblematic pattern across the colonizing periods of its emergent urban forms into the contemporary impositions of gated zones and territories. The enduring legacy of patrimonial power to Manila is to be found in the households and on the streets that undermine and devalue public forms of social power in favour of the patriarch and his householders ( now relabeled as ‘shareholders‘ in ‘public companies’) at the cost of harmonious, peaceable and just public order. -

BUS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

BUS bus time schedule & line map BUS Alabang - Plaza Lawton View In Website Mode The BUS bus line (Alabang - Plaza Lawton) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, Manila →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City →Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BUS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BUS bus arriving. Direction: Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, BUS bus Time Schedule Manila →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, 66 stops Manila →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, Manila Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Lexicor Building Alabang-Zapote Road, Philippines Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, Manila GM Homes, Philippines Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Sm South Mall Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Alabang-Zapote Road / Southmall Access Rd Intersection, Muntinlupa City, Manila Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Alabang-Zapote Road, Las Piñas City, Manila Alabang-Zapote Road, Las Piñas City, Manila 404 Alabang-Zapote Road, Philippines BUS bus Info Direction: Alabang-Zapote Road, Muntinlupa City, Alabang-Zapote Road, Las Piñas City, Manila Manila →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Stops: 66 Unilever, Alabang-Zapote Road, Las Piñas City, Trip Duration: 119 min Manila Line Summary: Alabang-Zapote -

Nytårsrejsen Til Filippinerne – 2014

Nytårsrejsen til Filippinerne – 2014. Martins Dagbog Dorte og Michael kørte os til Kastrup, og det lykkedes os at få en opgradering til business class - et gammelt tilgodebevis fra lidt lægearbejde på et Singapore Airlines fly. Vi fik hilst på vore 16 glade gamle rejsevenner ved gaten. Karin fik lov at sidde på business class, mens jeg sad på det sidste sæde i økonomiklassen. Vi fik julemad i flyet - flæskesteg med rødkål efterfulgt af ris á la mande. Serveringen var ganske god, og underholdningen var også fin - jeg så filmen "The Hundred Foot Journey", som handlede om en indisk familie, der åbner en restaurant lige overfor en Michelin-restaurant i en mindre fransk by - meget stemningsfuld og sympatisk. Den var instrueret af Lasse Hallström. Det tog 12 timer at flyve til Singapore, og flyet var helt fuldt. Flytiden mellem Singapore og Manila var 3 timer. Vi havde kun 30 kg bagage med tilsammen (12 kg håndbagage og 18 kg i en indchecket kuffert). Jeg sad ved siden af en australsk student, der skulle hjem til Perth efter et halvt år i Bergen. Hans fly fra Lufthansa var blevet aflyst, så han havde måttet vente 16 timer i Københavns lufthavn uden kompensation. Et fly fra Air Asia på vej mod Singapore forulykkede med 162 personer pga. dårligt vejr. Miriams kuffert var ikke med til Manilla, så der måtte skrives anmeldelse - hun fik 2200 pesos til akutte fornødenheder. Vi vekslede penge som en samlet gruppe for at spare tid og gebyr - en $ var ca. 45 pesos. Vi kom i 3 minibusser ind til Manila Hotel, hvor det tog 1,5 time at checke os ind på 8 værelser. -

Vital Tourism Statistics and Information on 18 Asian Countries

PPS 1789/06/2012(022780) 2011/2012 Vital tourism statistics PRODUCED BY and information on 18 Asian countries ATG1112 p01 cover.indd 1 12/14/11 12:14 PM 2 ASIAN TOURISM GUIDE 2011/2012 EDITORIAL Raini Hamdi Group Editor ([email protected]) Gracia Chiang Editor, TTG Asia ([email protected]) Karen Yue Editor, TTGmice ([email protected]) Brian Higgs Editor, TTG Asia Online ([email protected]) Linda Haden Assistant Editor ([email protected]) Amee Enriquez Senior Sub-editor ([email protected]) Sirima Eamtako Editor, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos ([email protected]) With contributors Byron Perry, Rahul Khanna, Vashira Anonda Mimi Hudoyo Editor, Indonesia ([email protected]) Sim Kok Chwee Correspondent-at-large ([email protected]) N. Nithiyananthan Chief Correspondent, Malaysia ([email protected]) Marianne Carandang Correspondent, The Philippines ([email protected]) Maggie Rauch Correspondent, China ([email protected]) Prudence Lui Correspondent, Hong Kong ([email protected]) Glenn Smith Correspondent, Taiwan ([email protected]) Shekhar Niyogi Chief Correspondent, India ([email protected]) Anand and Madhura Katti Correspondent, India ([email protected]) Feizal Samath Correspondent, Sri Lanka ([email protected]) Redmond Sia, Haze Loh Creative Designers 2011/2012 Lina Tan Editorial Assistant SALES & MARKETING Michael Chow Publisher ([email protected]) Katherine Ng, Marisa Chen Senior Business Managers ([email protected], -

Baguio City, Philippines Area By

A Landslide Risk Rating System for the Baguio City, Philippines Area by Artessa Niccola D. Saldivar-Sali B.S., Civil Engineering (2002) University of the Philippines Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology MASSACHUSETTS INS E June 2004 OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 7 2004 0 2004 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved LIBRARIES Signature of Author ............................ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 24, 2004 Certified by ............................................... / .................................. Herbert H. Einstein Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering /I A Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ........................... Heidi Nepf Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students BARKER A LANDSLIDE RISK RATING SYSTEM FOR THE BAGUIO CITY, PHILIPPINES AREA by ARTESSA NICCOLA D. SALDIVAR-SALI Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 24, 2004 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT This research formulates a LANDSLIDE RISK RATING SYSTEM for the Greater Baguio area in the Philippines. It is hoped that the tool will be made a part of the physical/urban planning process when used by engineers and planners and used to address risks posed by landslides given the rapidly increasing concentration of population and the development of infrastructure and industry in the Baguio area. Reports and studies of individual landslides in the area are reviewed in order to discover the causal factors of mass movements and their interactions. The findings of these research works are discussed in the first portion of this paper.