Examining the Rhetoric of Radicalisation Abdul Abdullah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: a Comparative

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Australian National University 1 Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: A Comparative Study of Political Parties Online This is a pre-print for: R. Ackland and R. Gibson (2013), “Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: A Comparative Study of Political Parties Online,” International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(3), special issue on Computational Social Science: Research Strategies, Design & Methods, 231-244. Dr. Robert Ackland, Research Fellow at the Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia *Professor Rachel Gibson, Professor of Politics, Institute for Social Change, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. *Corresponding author: Professor Rachel Gibson Institute for Social Change University of Manchester, Oxford Road Manchester M13 9PL UK Ph: + 44 (0)161 306 6933 Fax: +44 (0) 161 275 0793 [email protected] Word count: 6,062(excl title page and key words) 2 Abstract This paper analyses hyperlink data from over 100 political parties in six countries to show how political actors are using links to engage in a new form of ‘networked communication’ to promote themselves to an online audience. We specify three types of networked communication - identity reinforcement, force multiplication and opponent dismissal - and hypothesise variance in their performance based on key party variables of size and ideological outlook. We test our hypotheses using an original comparative hyperlink dataset. The findings support expectations that hyperlinks are being used for networked communication by parties, with identity reinforcement and force multiplication being more common than opponent dismissal. The results are important in demonstrating the wider communicative significance of hyperlinks, in addition to their structural properties as linkage devices for websites. -

George Gittoes: I Witness Teachers' Notes

GEORGE GITTOES: I WITNESS TEACHERS’ NOTES George Gittoes, Evolution 2014, oil on paper INTRODUCTION “I believe in art so much that I am prepared to risk my life to do it. I physically go to these places. I also believe an artist can actually see and show things about what's going on that a paid professional journalist can't and won't do, and can show a level of humanity and complexity that they wouldn't cover on TV.” - George Gittoes George Gittoes: I Witness is the first major exhibition in Australia of the work of artist and film maker George Gittoes which surveys the last 45 years of his incredible career. Internationally recognised for working and creating art in regions of conflict around the world he has been an eye witness to war and human excess, and also to the possibilities of compassion. Beginning his career in the late 1960s, Gittoes was part of a group of artists including Brett Whiteley and Martin Sharp who established The Yellow House artist community in Sydney. This was followed by his move to Bundeena in the Sutherland region where he became an influential and instrument figure in community art projects and the development of Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre. In the 1980s Gittoes began travelling to areas of conflict and his tireless energy for pushing the boundaries of art making has since seen him working in some of the most dangerous and difficult places on earth. He first travelled to Nicaragua and the Philippines, then the Middle East, Rwanda and Cambodia in the 1990s and more recently to Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation Policies on Asian Immigration and Multiculturalism

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation policies on Asian immigration and multiculturalism 仍然反亚裔?反华裔? 一国党针对亚裔移民和多元文化 的政策 Is Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party anti-Asian? Just how much has One Nation changed since Pauline Hanson first sat in the Australian Parliament two decades ago? This report reviews One Nation’s statements of the 1990s and the current policies of the party. It concludes that One Nation’s broad policies on immigration and multiculturalism remain essentially unchanged. Anti-Asian sentiments remain at One Nation’s core. Continuity in One Nation policy is reinforced by the party’s connections with anti-Asian immigration campaigners from the extreme right of Australian politics. Anti-Chinese thinking is a persistent sub-text in One Nation’s thinking and policy positions. The possibility that One Nation will in the future turn its attacks on Australia's Chinese communities cannot be dismissed. 宝林·韩森的一国党是否反亚裔?自从宝林·韩森二十年前首次当选澳大利亚 议会议员以来,一国党改变了多少? 本报告回顾了一国党在二十世纪九十年代的声明以及该党的现行政策。报告 得出的结论显示,一国党关于移民和多元文化的广泛政策基本保持不变。反 亚裔情绪仍然居于一国党的核心。通过与来自澳大利亚极右翼政坛的反亚裔 移民竞选人的联系,一国党的政策连续性得以加强。反华裔思想是一国党思 想和政策立场的一个持久不变的潜台词。无法排除一国党未来攻击澳大利亚 华人社区的可能性。 Report Philip Dorling May 2017 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. -

We're Not Nazis, But…

August 2014 American ideals. Universal values. Acknowledgements On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. This report was made possible by the generous Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to support of the David Berg Foundation and Arthur & look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Toni Rembe Rock. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s Human Rights First has for many years worked to a vital national interest. America is strongest when our combat hate crimes, antisemitism and anti-Roma policies and actions match our values. discrimination in Europe. This report is the result of Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and trips by Sonni Efron and Tad Stahnke to Greece and action organization that challenges America to live up to Hungary in April, 2014, and to Greece in May, 2014, its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in as well as interviews and consultations with a wide the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. range of human rights activists, government officials, government and private companies to respect human national and international NGOs, multinational rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to bodies, scholars, attorneys, journalists, and victims. demand reform, accountability, and justice. Around the We salute their courage and dedication, and give world, we work where we can best harness American heartfelt thanks for their counsel and assistance. influence to secure core freedoms. We are also grateful to the following individuals for We know that it is not enough to expose and protest their work on this report: Tamas Bodoky, Maria injustice, so we create the political environment and Demertzian, Hanna Kereszturi, Peter Kreko, Paula policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect Garcia-Salazar, Hannah Davies, Erica Lin, Jannat for human rights. -

The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’S Radicalization and Attack Planning

The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’s Radicalization and Attack Planning Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Chelsea Daymon and Amarnath Amarasingam i The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’s Radicalization and Attack Planning Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Chelsea Daymon and Amarnath Amarasingam ICCT Perspective December 2020 ii About ICCT The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) is an independent think and do tank providing multidisciplinary policy advice and practical, solution- oriented implementation support on prevention and the rule of law, two vital pillars of effective counterterrorism. ICCT’s work focuses on themes at the intersection of countering violent extremism and criminal justice sector responses, as well as human rights-related aspects of counterterrorism. The major project areas concern countering violent extremism, rule of law, foreign fighters, country and regional analysis, rehabilitation, civil society engagement and victims’ voices. Functioning as a nucleus within the international counter-terrorism network, ICCT connects experts, policymakers, civil society actors and practitioners from different fields by providing a platform for productive collaboration, practical analysis, and exchange of experiences and expertise, with the ultimate aim of identifying innovative and comprehensive approaches to preventing and countering terrorism. Licensing and Distribution ICCT publications are published in open access format and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Mapping Right-Wing Extremism in Victoria Applying a Gender Lens to Develop Prevention and Deradicalisation Approaches

MAPPING RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM IN VICTORIA APPLYING A GENDER LENS TO DEVELOP PREVENTION AND DERADICALISATION APPROACHES Authors: Dr Christine Agius, Associate Professor Kay Cook, Associate Professor Lucy Nicholas, Dr Ashir Ahmed, Dr Hamza bin Jehangir, Noorie Safa, Taylor Hardwick & Dr Sally Clark. This research was supported by the Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety Acknowledgments We would like to thank Dr Robin Cameron, Professor Laura Shepherd and Dr Shannon Zimmerman for their helpful advice and support. We also thank the stakeholders who participated in this research for their important feedback and insights which helped shape this report. All authors were employees of Swinburne University of Technology for the purpose of this research, except for Associate Professor Lucy Nicholas who is employed by Western Sydney University. Publication Design by Mina Teh, Swinburne Design Bureau. Disclaimer This report does not constitute Victorian Government policy. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Victorian Government. Suggested Citation Agius C, Cook K, Nicholas L, Ahmed A, bin Jehangir H, Safa N, Hardwick T & Clark S. (2020). Mapping right-wing extremism in Victoria. Applying a gender lens to develop prevention and deradicalisation approaches. Melbourne: Victorian Government, Department of Justice and Community Safety: Countering Violent Extremism Unit and Swinburne University of Technology. ISBN: 978-1-925761-24-5 (Print) 978-1-925761-25-2 (Digital) DOI: https://doi.org/10.25916/5f3a26da94911 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 2 Background 2 Aims 2 Main Findings 2 Policy Considerations 2 Glossary 3 A. Project Overview 6 Overview and Background 6 Aims and Objectives 6 Scope and Gap 6 B. -

Donald Trump, the Changes: Aanti

Ethnic and Racial Studies ISSN: 0141-9870 (Print) 1466-4356 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution Ed Pertwee To cite this article: Ed Pertwee (2020): Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution, Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 17 Apr 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 193 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rers20 ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688 Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution Ed Pertwee Department of Sociology, London School of Economics, London, UK ABSTRACT This article explores the “counter-jihad”, a transnational field of anti-Muslim political action that emerged in the mid-2000s, becoming a key tributary of the recent far- right insurgency and an important influence on the Trump presidency. The article draws on thematic analysis of content from counter-jihad websites and interviews with movement activists, sympathizers and opponents, in order to characterize the counter-jihad’s organizational infrastructure and political discourse and to theorize its relationship to fascism and other far-right tendencies. Although the political discourses of the counter-jihad, Trumpian Republicanism and the avowedly racist “Alt-Right” are not identical, I argue that all three tendencies share a common, counterrevolutionary temporal structure. -

Brenton Tarrant: the Processes Which Brought Him to Engage in Political Violence

CSTPV Short Papers Brenton Tarrant: the processes which brought him to engage in political violence Beatrice Williamson 1 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 Brenton Tarrant .................................................................................................................... 3 Conceptualising Tarrant and his violence ............................................................................. 5 The Lone Actor Puzzle ........................................................................................................... 5 ‘A dark social web’: online ‘radicalisation’ ............................................................................ 7 Online communities: Social Network Ties and Framing .................................................... 7 Funnelling and Streams ..................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 11 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 12 2 Introduction Individual radicalisation is a complex and bespoke process influenced by multiple factors and variables, meaning every individual follows their own path to terrorism and political violence. This paper will endeavour to demonstrate and explore some of the -

Printmaking and the Language of Violence

PRINTMAKING AND THE LANGUAGE OF VIOLENCE by Yvonne Rees-Pagh Graduate Diploma of Arts (Visual Arts) Monash University Master Of Visual Arts Monash University Master of Fine Arts University of Tasmania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania MARCH 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 i This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge and thank my supervisors Milan Milojevic and Dr Llewellyn Negrin for their advice, assistance and support throughout the project. I am eternally grateful to my partner in life Bevan for his patience and encouragement throughout the project, and care when I needed it most. DEDICATION I dedicate this project to the memory of my dearest friend Olga Vlasova, the late Curator of Prints, Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Printmaking brought us together in a lasting friendship that began in Tomsk, Siberia in 1990. iii CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................. 01 Introduction ....................................................................................... 02 Chapter One: The Central Argument Towards violence ..................................................................... 07 Violence and the power of etching .......................................... -

Violent Extremism, Misinformation, Defamation, and Cyberharassment

STANFORD How to Reconcile International Human Rights Law and Criminalization of Online Speech: Violent Extremism, Misinformation, Defamation, and Cyberharassment 2019-2020 PRACTICUM RESEARCH TEAM Amélie-Sophie VAVROVSKY Justin WONG Anirudh JAIN Madeline LIBBEY Asaf ZILBERFARB Madeline MAGNUSON David JAFFE Naz GOCEK Eric FRANKEL Nil Sifre TOMAS Jasmine SHAO Shalini IYENGAR June LEE Sydney FRANKENBERG INSTRUCTORS AND PROJECT LEADS: Sarah SHIRAZYAN, Ph.D. Lecturer in Law Allen WEINER Senior Lecturer in Law, Director, Stanford Program in International and Comparative Law Yvonne LEE, M.A. Teaching Assistant Madeline Magnuson, J.D. Research Assistant ABOUT THE STANFORD LAW SCHOOL POLICY LAB Engagement in public policy is a core mission of teaching and research at Stanford Law School (SLS). The Law and Policy Lab (The Policy Lab) offers students an immersive experience in finding solutions to some of the world’s most pressing issues. Under the guidance of seasoned faculty advisers, Policy Lab students counsel real-world clients in an array of areas, including education, global governance, transnational law enforcement, intellectual property, policing and technology, and energy policy. Policy labs address policy problems for real clients, using analytic approaches that supplement traditional legal analysis. The clients may be local, state, federal and international public agencies or officials, or private non-profit entities such as NGOs and foundations. Typically, policy labs assist clients in deciding whether and how qualitative and/or quantitative empirical evidence can be brought to bear to better understand the nature or magnitude of their particular policy problem and identify and assess policy options. The methods may include comparative case studies, population surveys, stakeholder interviews, experimental methods, program evaluation or big data science, and a mix of qualitative and quantitative analysis. -

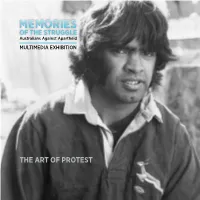

The Art of Protest

MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 1 THE ART OF PROTEST MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION THE ART OF PROTEST THE ART OF PROTEST 2014 Customs House Sydney University of Pretoria MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 2016 Museum of Australian Democracy Canberra Protest in Sydney including from left to right Eddie Funde, ACTU President Cliff Dolan, Maurie Keane MP, Senator 2017 The Castle of Good Hope Bruce Childs and Johnny Makateni. Photo: State Library of NSW & Search Foundation Cape Town Voices and Memories ANGUS LEENDERTZ | CURATOR THE ASAA TEAM CONTRIBUTORS The global anti-apartheid movement was arguably the greatest social movement of CURATOR Angus Leendertz Father Richard Buchhorn the 20th century and Australia can be very proud of the important role it played in Will Butler and Pamela Curry – Australian High Commission Pretoria, ASSISTANT CURATORS the demise of apartheid. The history of the anti-apartheid movement in Australia Tracy Dunn (Director Ephemera Research & Logistics, University of Pretoria Exhibition 2014 Collections) & James Mohr David Corbet – University of Pretoria Catalogue Design from 1950 to1994 was a story waiting to be told. Ken Davis & Dr Helen McCue – APHEDA (Union Aid Abroad) MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIAN Introduction DEMOCRACY CURATOR Professor Andrea Durbach – HRC Centre, University of New South Wales Libby Stewart Professor Gareth Evans – Former Australian Mininister of Foreign Affairs In this exhibition, you will hear the voices and In 1997, I responded to Nelson Mandela’s general call memories of some of the Australians, South Africans for skilled South Africans to return to their country ASAA REFERENCE GROUP Dr Gary Foley – Victoria University and people of other nations who worked hard of birth and assist in building the new free South Kerry Browning Eddie Funde – ANC Australia over decades to bring about the end of apartheid.