Swansea University,Kyknos Seminar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis

GOLDFARB, BARRY E., The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' "Alcestis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:2 (1992:Summer) p.109 The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis Barry E. Goldfarb 0UT ALCESTIS A. M. Dale has remarked that "Perhaps no f{other play of Euripides except the Bacchae has provoked so much controversy among scholars in search of its 'real meaning'."l I hope to contribute to this controversy by an examination of the philosophical issues underlying the drama. A radical tension between the values of philia and xenia con stitutes, as we shall see, a major issue within the play, with ramifications beyond the Alcestis and, in fact, beyond Greek tragedy in general: for this conflict between two seemingly autonomous value-systems conveys a stronger sense of life's limitations than its possibilities. I The scene that provides perhaps the most critical test for an analysis of Alcestis is the concluding one, the 'happy ending'. One way of reading the play sees this resolution as ironic. According to Wesley Smith, for example, "The spectators at first are led to expect that the restoration of Alcestis is to depend on a show of virtue by Admetus. And by a fine stroke Euripides arranges that the restoration itself is the test. At the crucial moment Admetus fails the test.'2 On this interpretation 1 Euripides, Alcestis (Oxford 1954: hereafter 'Dale') xviii. All citations are from this editon. 2 W. D. Smith, "The Ironic Structure in Alcestis," Phoenix 14 (1960) 127-45 (=]. R. Wisdom, ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Euripides' Alcestis: A Collection of Critical Essays [Englewood Cliffs 1968]) 37-56 at 56. -

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/xs25j Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Goneis in Athenian Law (And Perception)

GONEIS IN ATHENIAN LAW (AND PERCEPTION) David Whitehead Queen’s University Belfast [email protected] Abstract: This paper aims to establish what the laws of classical Athens meant when they used the term goneis. A longstanding and widespread orthodoxy holds that, despite the simple and largely unproblematic “dictionary” definition of the noun goneus/goneis as parent/parents, Athenian law extended it beyond an individual’s father and mother, so as to include – if they were still alive – protection and respect for his or her grandparents, and even great-grandparents. While this is not a notion of self-evident absurdity, I challenge it on two associated counts, one broad and one narrow. On a general, contextual level, genre-by genre survey and analysis of the evidence for what goneus means (and implies) in everyday life and usage shows, in respect of the word itself, an irresistible thrust in favour of the literal ‘parent’ sense. Why then think otherwise? Because of confusion, in modern minds, engendered by Plato and by Isaeus. In Plato’s case, his legislation for Magnesia contemplates (I argue) legal protection for grandparents but does not, by that mere fact, extend the denotation of goneis to them. And crucially for a proper understanding of the law(s) of Athens itself, two much-cited passages in the lawcourt speeches of Isaeus, 1.39 and 8.32, turn out to be the sole foundation for the modern misunderstanding about the legal scope of goneis. They should be recognised for what they are: passages where law is secondary and rhetorical persuasion paramount. -

Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2009 A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. "A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' 'Orphic' Creation of Mankind." American Journal of Philology 130, no. 4 (2009): 511-532. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III “A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' ‘Orphic’ Creation of Mankind” American Journal of Philology 130 (2009), pp. 511–532. A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' Creation of Mankind Olympiodorus' recounting (In Plat. Phaed. I.3-6) of the Titan's dismemberment of Dionysus and the subsequent creation of humankind has served for over a century as the linchpin of the reconstructions of the supposed Orphic doctrine of original sin. From Comparetti's first statement of the idea in his 1879 discussion of the gold tablets from Thurii, Olympiodorus' brief testimony has been the -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Feasting in Homeric Epic 303

HESPERIA 73 (2004) FEASTING IN Pages 301-337 HOMERIC EPIC ABSTRACT Feasting plays a centralrole in the Homeric epics.The elements of Homeric feasting-values, practices, vocabulary,and equipment-offer interesting comparisonsto the archaeologicalrecord. These comparisonsallow us to de- tect the possible contribution of different chronologicalperiods to what ap- pearsto be a cumulative,composite picture of around700 B.c.Homeric drink- ing practicesare of particularinterest in relation to the history of drinkingin the Aegean. By analyzing social and ideological attitudes to drinking in the epics in light of the archaeologicalrecord, we gain insight into both the pre- history of the epics and the prehistoryof drinkingitself. THE HOMERIC FEAST There is an impressive amount of what may generally be understood as feasting in the Homeric epics.' Feasting appears as arguably the single most frequent activity in the Odysseyand, apart from fighting, also in the Iliad. It is clearly not only an activity of Homeric heroes, but also one that helps demonstrate that they are indeed heroes. Thus, it seems, they are shown doing it at every opportunity,to the extent that much sense of real- ism is sometimes lost-just as a small child will invariablypicture a king wearing a crown, no matter how unsuitable the circumstances. In Iliad 9, for instance, Odysseus participates in two full-scale feasts in quick suc- cession in the course of a single night: first in Agamemnon's shelter (II. 1. thanks to John Bennet, My 9.89-92), and almost immediately afterward in the shelter of Achilles Peter Haarer,and Andrew Sherrattfor Later in the same on their return from their coming to my rescueon variouspoints (9.199-222). -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

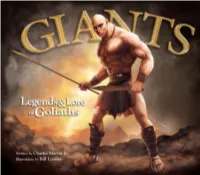

Giants: Legends & Lore of Goliaths

PERHAPS MYTHOLOGY CONTAINS MORE TRUTH THAN WE REALIZE! The word “myth” has come to mean “fiction” in our minds, and so some people take Bible accounts, Aesop’s fables, and Greek myths and place them all in the same category. But what if some of the old legends are true? Rather than dismiss these narratives, perhaps we should investigate them. In this case, the world is filled with giant legends that speak of heroes and wars. In this highly engaging book of giants you will discover ? Unique glimpses into the ancient accounts of giants from around the world @ What does the Bible say about giants? ? Full-color artistry developed in an interactive format with fold outs and flaps, booklets, and more! @ A spectacular center spread stretching 4-feet across! It is fascinating that the ancient world agreed on many aspects of the Martin Bible, one of these being that early in the history of mankind, a race of violent, yet intelligent giants walked the earth, were destroyed by the Flood. Through historical records, the pre-Flood and post-Flood worlds are reconstructed, with giants re-emerging in and around Israel, and you’ll see one more reason that the Bible can be trusted. RELIGION/Biblical Studies/General JUVENILE NONFICTION/Religious/ Christian/General $18.99 U.S. ISBN-13: 978-0-89051-864-9 EAN First printing: June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Master Books. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used Odysseus Blinds Polyphemus or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. -

Mercury (Mythology) 1 Mercury (Mythology)

Mercury (mythology) 1 Mercury (mythology) Silver statuette of Mercury, a Berthouville treasure. Ancient Roman religion Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludi mystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · Augur Vestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis Dii Consentes Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres Mercury (mythology) 2 Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn · Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities Related topics Roman mythology Glossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Mercury ( /ˈmɜrkjʉri/; Latin: Mercurius listen) was a messenger,[1] and a god of trade, the son of Maia Maiestas and Jupiter in Roman mythology. His name is related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages).[2] In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, but most of his characteristics and mythology were borrowed from the analogous Greek deity, Hermes. Latin writers rewrote Hermes' myths and substituted his name with that of Mercury. However, there are at least two myths that involve Mercury that are Roman in origin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome. In Ovid's Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld.