Astronomers' Observing Guides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting

Program Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting June 12–14, 2018 • Knoxville, Tennessee Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Science Organizing Committee David Williams, Chair Arizona State University Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Robert Jacobsen Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Bradley Thomson Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/pgm2018/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2018) Title of abstract. In Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting, Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2066, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Guide to Sessions Tuesday, June 12, 2018 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Introduction and Mercury and Venus Maps 1:00 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Mars Maps 5:30 p.m. Strong Hall Poster Area Poster Session: 2018 Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Wednesday, June 13, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room GIS and Planetary Mapping Techniques and Lunar Maps 1:15 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Asteroid, Dwarf Planet, and Outer Planet Satellite Maps Thursday, June 14, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Optional Field Trip to Appalachian Mountains Program Tuesday, June 12, 2018 INTRODUCTION AND MERCURY AND VENUS MAPS 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Chairs: David Williams Devon Burr 9:00 a.m. -

Thermal Studies of Martian Channels and Valleys Using Termoskan Data

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 99, NO. El, PAGES 1983-1996, JANUARY 25, 1994 Thermal studiesof Martian channelsand valleys using Termoskan data BruceH. Betts andBruce C. Murray Divisionof Geologicaland PlanetarySciences, California Institute of Technology,Pasadena The Tennoskaninstrument on boardthe Phobos '88 spacecraftacquired the highestspatial resolution thermal infraredemission data ever obtained for Mars. Included in thethermal images are 2 km/pixel,midday observations of severalmajor channel and valley systems including significant portions of Shalbatana,Ravi, A1-Qahira,and Ma'adimValles, the channelconnecting Vailes Marineris with HydraotesChaos, and channelmaterial in Eos Chasma.Tennoskan also observed small portions of thesouthern beginnings of Simud,Tiu, andAres Vailes and somechannel material in GangisChasma. Simultaneousbroadband visible reflectance data were obtainedfor all but Ma'adimVallis. We find thatmost of the channelsand valleys have higher thermal inertias than their surroundings,consistent with previousthermal studies. We show for the first time that the thermal inertia boundariesclosely match flat channelfloor boundaries.Also, butteswithin channelshave inertiassimilar to the plainssurrounding the channels,suggesting the buttesare remnants of a contiguousplains surface. Lower bounds ontypical channel thermal inertias range from 8.4 to 12.5(10 -3 cal cm-2 s-1/2 K-I) (352to 523 in SI unitsof J m-2 s-l/2K-l). Lowerbounds on inertia differences with the surrounding heavily cratered plains range from 1.1 to 3.5 (46 to 147 sr). Atmosphericand geometriceffects are not sufficientto causethe observedchannel inertia enhancements.We favornonaeolian explanations of the overall channel inertia enhancements based primarily upon the channelfloors' thermal homogeneity and the strongcorrelation of thermalboundaries with floor boundaries. However,localized, dark regions within some channels are likely aeolian in natureas reported previously. -

Evidence for Volcanism in and Near the Chaotic Terrains East of Valles Marineris, Mars

43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2012) 1057.pdf EVIDENCE FOR VOLCANISM IN AND NEAR THE CHAOTIC TERRAINS EAST OF VALLES MARINERIS, MARS. Tanya N. Harrison, Malin Space Science Systems ([email protected]; P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA 92191). Introduction: Martian chaotic terrain was first de- ple chaotic regions are visible in CTX images (Figs. scribed by [1] from Mariner 6 and 7 data as a “rough, 1,2). These fractures have widened since the formation irregular complex of short ridges, knobs, and irregular- of the flows. The flows overtop and/or bank up upon ly shaped troughs and depressions,” attributing this pre-existing topography such as crater ejecta blankets morphology to subsidence and suggesting volcanism (Fig. 2c). Flows are also observed originating from as a possible cause. McCauley et al. [2], who were the fractures within some craters in the vicinity of the cha- first to note the presence of large outflow channels that os regions. Potential lava flows are observed on a por- appeared to originate from the chaotic terrains in Mar- tion of the floor as Hydaspis Chaos, possibly associat- iner 9 data, proposed localized geothermal melting ed with fissures on the chaos floor. As in Hydraotes, followed by catastrophic release as the formation these flows bank up against blocks on the chaos floor, mechanism of chaotic terrain. Variants of this model implying that if the flows are volcanic in origin, the have subsequently been detailed by a number of au- volcanism occurred after the formation of Hydaspis thors [e.g. 3,4,5]. Meresse et al. -

DATING the RESURFACING EVENTS of the HARMAKHIS VALLIS SOURCE REGIONS, MARS: PRELIMINARY RESULTS. S. Kukkonen and V.-P

44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013) 2140.pdf DATING THE RESURFACING EVENTS OF THE HARMAKHIS VALLIS SOURCE REGIONS, MARS: PRELIMINARY RESULTS. S. Kukkonen and V.-P. Kostama, Astronomy, Department of Physics, P.O. Box 3000, FI-90014 University of Oulu, Finland ([email protected]). Introduction: Harmakhis Vallis is one of the four [e.g., 15–17]. Usually they have been excluded from major outflow channel systems that cut the eastern Hel- the crater counts because of the uncertainty of their las rim region of Mars (Fig. 1). It is ~800 km long and origin (primary vs. secondary crater). However, small located ~450 km south of Hadriaca Patera starting craters accumulate to the surface more quickly than close to the end of another valley, Reull Vallis. Due to larger ones, and thus the high spatial resolution is nec- the close position to the volcanic features, the channels essary in dating younger surfaces or small units where are suggested to have been formed by the mobilization there are only few large craters. In the case of Harma- and release of subsurface volatiles by volcanic heat [1– khis Vallis, the region has experienced significant re- 5]. Because Harmakhis Vallis cuts the surrounding cent modification and degradation, and thus, we can massifs of the cratered terrains, it is clearly one of the assume that the small crater population mostly post- youngest features in the region [6, 7]. dates the secondary craters forming larger impacts lo- cated in the older regions. Therefore, only the obvious clusters of secondary craters were excluded from the counts. -

Volcanism on Mars

Author's personal copy Chapter 41 Volcanism on Mars James R. Zimbelman Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA William Brent Garry and Jacob Elvin Bleacher Sciences and Exploration Directorate, Code 600, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA David A. Crown Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 717 7. Volcanic Plains 724 2. Background 718 8. Medusae Fossae Formation 725 3. Large Central Volcanoes 720 9. Compositional Constraints 726 4. Paterae and Tholi 721 10. Volcanic History of Mars 727 5. Hellas Highland Volcanoes 722 11. Future Studies 728 6. Small Constructs 723 Further Reading 728 GLOSSARY shield volcano A broad volcanic construct consisting of a multitude of individual lava flows. Flank slopes are typically w5, or less AMAZONIAN The youngest geologic time period on Mars identi- than half as steep as the flanks on a typical composite volcano. fied through geologic mapping of superposition relations and the SNC meteorites A group of igneous meteorites that originated on areal density of impact craters. Mars, as indicated by a relatively young age for most of these caldera An irregular collapse feature formed over the evacuated meteorites, but most importantly because gases trapped within magma chamber within a volcano, which includes the potential glassy parts of the meteorite are identical to the atmosphere of for a significant role for explosive volcanism. Mars. The abbreviation is derived from the names of the three central volcano Edifice created by the emplacement of volcanic meteorites that define major subdivisions identified within the materials from a centralized source vent rather than from along a group: S, Shergotty; N, Nakhla; C, Chassigny. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol

PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol. 26, No.3, September 1997 Articles 5 Projections from Gallatin .................................................... Gary Likert 10 How Thinking Goes Wrong ....................................... Michael Shermer 17 Astronomy Link - A Beginning ........................................ Jim Manning 21 14th International Planetarium Conference ................................ IPS'98 Features 26 Opening the Dome .............................................................. Jon U. Bell 29 Planetarium Memories .........., .................................. Kenneth E. Perkins 31 Planetechnica: Shoestring Wire Management ......... Richard McColman 34 Forum ................................................................................. Steve Tidey 39 Book Reviews .................................................................. April S. Whitt 45 Mobile News Network ...................................................... Sue Reynolds 47 ',X/hat's New ...................................................................... Jim Manning 51 Gibbous Gazette ......................................................... Christine Shupla 53 Regional Roundup ............................................................ Lars Broman 58 President's Message ....................................................... Thomas Kraupe 62 Jane's Corner .................................................................... Jane Hastings " l1,c ZKPJ ;'\' jalltastic ... It IJrojec/x Ih e 11/ 0 0 1/ phases wilh (l -

Pre-Mission Insights on the Interior of Mars Suzanne E

Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars Suzanne E. Smrekar, Philippe Lognonné, Tilman Spohn, W. Bruce Banerdt, Doris Breuer, Ulrich Christensen, Véronique Dehant, Mélanie Drilleau, William Folkner, Nobuaki Fuji, et al. To cite this version: Suzanne E. Smrekar, Philippe Lognonné, Tilman Spohn, W. Bruce Banerdt, Doris Breuer, et al.. Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars. Space Science Reviews, Springer Verlag, 2019, 215 (1), pp.1-72. 10.1007/s11214-018-0563-9. hal-01990798 HAL Id: hal-01990798 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01990798 Submitted on 23 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte (OATAO ) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the wor of some Toulouse researchers and ma es it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author's version published in: https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/21690 Official URL : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-018-0563-9 To cite this version : Smrekar, Suzanne E. and Lognonné, Philippe and Spohn, Tilman ,... [et al.]. Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars. (2019) Space Science Reviews, 215 (1). -

In Pdf Format

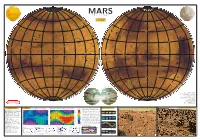

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

USGS Open-File Report 2006-1263

Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of Planetary Geologic Mappers, Nampa, Idaho 2006 Edited By Tracy K.P. Gregg,1 Kenneth L. Tanaka,2 and R. Stephen Saunders3 Open-File Report 2006-1263 2006 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1 The State University of New York at Buffalo, Department of Geology, 710 Natural Sciences Complex, Buffalo, NY 14260-3050. 2 U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001. 3 NASA Headquarters, Office of Space Science, 300 E. Street SW, Washington, DC 20546. Report of the Annual Mappers Meeting Northwest Nazarene University Nampa, Idaho June 30 – July 2, 2006 Approximately 18 people attended this year’s mappers meeting, and many more submitted abstracts and maps in absentia. The meeting was held on the campus of Northwest Nazarene University (NNU), and was graciously hosted by NNU’s School of Health and Science. Planetary mapper Dr. Jim Zimbelman is an alumnus of NNU, and he was pivotal in organizing the meeting at this location. Oral and poster presentations were given on Friday, June 30. Drs. Bill Bonnichsen and Marty Godchaux led field excursions on July 1 and 2. USGS Astrogeology Team Chief Scientist Lisa Gaddis led the meeting with a brief discussion of the status of the planetary mapping program at USGS, and a more detailed description of the Lunar Mapping Program. She indicated that there is now a functioning website (http://astrogeology.usgs.gov/Projects/PlanetaryMapping/Lunar/) which shows which lunar quadrangles are available to be mapped. -

Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of Planetary Geologic Mappers, Flagstaff, AZ 2014

Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of Planetary Geologic Mappers, Flagstaff, AZ 2014 Edited by: James A. Skinner, Jr. U. S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff, AZ David Williams Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ NOTE: Abstracts in this volume can be cited using the following format: Graupner, M. and Hansen, V.L., 2014, Structural and Geologic Mapping of Tellus Region, Venus, in Skinner, J. A., Jr. and Williams, D. A., eds., Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of Planetary Geologic Mappers, Flagstaff, AZ, June 23-25, 2014. SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Monday, June 23– Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Time Planet/Body Topic 8:30 am Arrive/Set-up – 2255 N. Gemini Drive (USGS) 9:00 Welcome/Logistics 9:10 NASA HQ and Program Remarks (M. Kelley) 9:30 USGS Map Coordinator Remarks (J. Skinner) 9:45 GIS and Web Updates (C. Fortezzo) 10:00 RPIF Updates (J. Hagerty) 10:15 BREAK / POSTERS 10:40 Venus Irnini Mons (D. Buczkowski) 11:00 Moon Lunar South Pole (S. Mest) 11:20 Moon Copernicus Quad (J. Hagerty) 11:40 Vesta Iterative Geologic Mapping (A. Yingst) 12:00 pm LUNCH / POSTERS 1:30 Vesta Proposed Time-Stratigraphy (D. Williams) 1:50 Mars Global Geology (J. Skinner) 2:10 Mars Terra Sirenum (R. Anderson) 2:30 Mars Arsia/Pavonis Montes (B. Garry) 2:50 Mars Valles Marineris (C. Fortezzo) 3:10 BREAK / POSTERS 3:30 Mars Candor Chasma (C. Okubo) 3:50 Mars Hrad Vallis (P. Mouginis-Mark) 4:10 Mars S. Margaritifer Terra (J. Grant) 4:30 Mars Ladon basin (C. Weitz) 4:50 DISCUSSION / POSTERS ~5:15 ADJOURN Tuesday, June 24 - Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Time Planet/Body Topic 8:30 am Arrive/Set-up/Logistics 9:00 Mars Upper Dao and Niger Valles (S. -

Évolution De Molécules Organiques En Conditions Martiennes Simulées

Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Paris Est (UPE) Ecole doctorale Sciences, Ingénierie et Environnement (SIE) Évolution de molécules organiques en conditions martiennes simulées Expériences en laboratoire et en orbite basse terrestre sur la Station Spatiale Internationale Présentée par : Laura ROUQUETTE Sciences de l’Univers et Environnement Spécialité Astronomie, Astrophysique Sous la direction de : Pr. Hervé Cottin et Dr. Fabien Stalport Soutenue le 19 novembre 2018 Composition du jury : Sylvain BERNARD Chargé de Recherche Rapporteur Grégoire DANGER Maître de Conférences Rapporteur Antonella BARUCCI Astronome Examinatrice Frances WESTALL Directrice de Recherche Présidente Hervé COTTIN Professeur Directeur de thèse Fabien STALPORT Maître de Conférences Co-directeur de thèse 2 3 4 Remerciements En classe de 5ème, comme tous mes camarades, j’ai eu droit au classique rendez-vous d’orientation avec une conseillère. Elle m’a demandé ce que je voulais faire plus tard. Je lui ai répondu « astrophysicienne » et comme beaucoup d’adultes avant elle, et encore d’autres après elle, elle s’est un peu moquée de mon ambition. Elle m’a néanmoins expliqué que je devais passer mon brevet des collèges, faire un bac S, une licence, un master, puis un doctorat. La route a été longue depuis ce rendez-vous d’orientation de 5ème au collège Jolimont de Toulouse, et la liste des personnes à remercier pour ce grade de « docteur », obtenu quatorze ans plus tard, l’est également. Je vais donc essayer de n’oublier personne, mais probablement en vain. Tout d’abord, merci à mes parents d’avoir été là, du début à la fin. De m’avoir appris que beaucoup de choses étaient possibles avec du travail, de ne pas avoir fait taire mes ambitions, de m’avoir valorisée tout au long de ma vie.