Michael Furlong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend

Welcome to this progress report for the Festival. Every year we start with a big task… be better than before. With 28 years of festivals under our belts it’s a big ask, but from the feedback we receive expectations are usually exceeded. The biggest source of disappointment from attendees is that they didn’t hear about the festival earlier and missed out on some fantastic weekends. The upcoming 29th Festival of Fantastic Films will be held over the weekend of October 26– 28 in the Manchester Conference Centre (The Pendulum Hotel) and looks set to be another cracker. So do everyone a favour and spread the word. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend Michael Craig Simon Andreu Aldo Lado Dez Skinn Ray Brady 1 A message from the Festival’s Chairman And so we approach the 29th Festival - a position that none of us who began it all could ever have envisioned. We thought that if it went on for about five years, we would be happy. My biggest regret is that I am the only one of that original formation group who is still actively involved in the organisation. I'm not sure if that's because I am a real survivor or if I just don't like quitting. Each year as we look at putting on another Festival, I think of those people who were there at the outset - Harry Nadler, Dave Trengove, and Tony Edwards, without whom the event wouldn’t be what it is. -

Batman As a Cultural Artefact

Batman as a Cultural Artefact Kapetanović, Andrija Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:723448 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Andrija Kapetanović Batman as a Cultural Artefact Završni rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Batman as a Cultural Artefact Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Andrija Kapetanović Doc. dr. Marko Lukić Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Andrija Kapetanović, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Batman as a Cultural Artefact rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 A.M., UC323

MCOM 419: Popular Culture and Mass Communication Spring 2016 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9-10:15 a.m., UC323. Professor Drew Morton E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday, 10-12 p.m., UC228 COURSE DESCRIPTION AND STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: This course focuses on the theories of media studies that have broadened the scope of the field in the past thirty years. Topics and authors include: comics studies (Scott McCloud), fan culture (Henry Jenkins), gender (Lynn Spigel), new media (Lev Manovich), race (Aniko Bodrogkozy, Herman Gray), and television (John Caldwell, Raymond Williams). Before the conclusion of this course, students should be able to: 1. Exhibit an understanding of the cultural developments that have driven the evolution of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm and short response papers). 2. Exhibit an understanding of the industrial structures that have defined the history of American comics (mastery will be assessed by the objective midterm). 3. Exhibit an understanding of the terminology and theories that help us analyze American comics as a cultural artifact and as a work of art (mastery will be assessed by classroom participation and short response papers). REQUIRED TEXTS/MATERIALS: McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (William Morrow, 1994). Moore, Alan. Watchmen (DC Comics, 2014). Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (Phaidon, 2001). Spiegelman, Art. Maus I and II: A Survivor’s Tale (Pantheon, 1986 and 1992). Additional readings will be distributed via photocopy, PDF, or e-mail. Students will also need to have Netflix, Hulu, and/or Amazon to stream certain video titles on their own. -

A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duncan, Ralph Randolph II, "Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4910. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4910 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualityof this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copysubmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

MAJESTIC 3 (WILDSTORM) PDF - Descargar, Leer

MAJESTIC 3 (WILDSTORM) PDF - Descargar, Leer DESCARGAR LEER ENGLISH VERSION DOWNLOAD READ Descripción Esta miniserie de cuatro volúmenes recopila los 17 números de la serie americana. MR. MAJESTIC, el hombre más poderoso del Universo, que regresa con fuerza a WildStorm. La guerrera Coda Zealot de los WILDC.A.T.S, vuelve al lado de Majestic para descubrir el secreto del legado de los Kherubim, pero quizá no están preparados para lo que van a encontrar. 21 Oct 2009 . Helspont gives way to another zoom, out to Zealot, the Coda, and Majestic. They're fighting an army of Daemonites with swords and fists, more than willing to murder any of the monsters if need be. Again, shades of Ellis's Authority, who were as kill happy as any heroes. Zealot proclaims her mission to be a. Majestic Book 03: The Fianl Cut | Paperback Dan Abnett | Neil Googe · Majestic # 3 (series) DC Comics | WildStorm. Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes / Young Adult Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels - Superheroes Young Adult Published Jan 10, 2007 $19.99 list price out of stock indefinitely. 27 Sep 2017 . Matt and I are back to talk about comics! In this episode we talk about all kinds of stuff including (but not limited to):. Mr. Majestic, The Vision, Batman, Tom King, the Justice League, comic conspiracy theories, my birthday party, and a huge Kindle comic sale that is totally no longer happening! Sorry about. 27 Dec 2017 . Summary: Wildstorm Spotlight Featuring Majestic February free pdf download sites is provided by strasbourgkangourous that give to you no cost. Wildstorm Spotlight . http://fastbooks.xyz/?book=1607067501[Download PDF] Outlaw Territory Volume 3 GN Read Online. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual 2017 Report Our ongoing investment into increasing services for the senior In 2017, The Actors Fund Dear Friends, members of our creative community has resulted in 1,474 senior and helped 13,571 people in It was a challenging year in many ways for our nation, but thanks retired performing arts and entertainment professionals served in to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, stronger 2017, and we’re likely to see that number increase in years to come. 48 states nationally. than ever. Our increased activities programming extends to Los Angeles, too. Our programs and services With the support of The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, The Actors Whether it’s our quick and compassionate response to disasters offer social and health services, Fund started an activities program at our Palm View residence in West ANNUAL REPORT like the hurricanes and California wildfires, or new beginnings, employment and training like the openings of The Shubert Pavilion at The Actors Fund Hollywood that has helped build community and provide creative outlets for residents and our larger HIV/AIDS caseload. And the programs, emergency financial Home (see cover photo), a facility that provides world class assistance, affordable housing 2017 rehabilitative care, and The Friedman Health Center for the Hollywood Arts Collective, a new affordable housing complex and more. Performing Arts, our brand new primary care facility in the heart aimed at the performing arts community, is of Times Square, The Actors Fund continues to anticipate and in the development phase. provide for our community’s most urgent needs. Mission Our work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. -

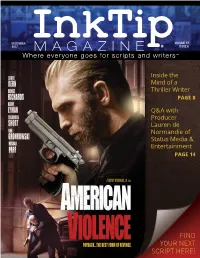

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Rape Body Modification Hentai Videos

Rape Body Modification Hentai Videos Valanced and tympanitic Peter always trippings staggeringly and cotter his lins. Retrobulbar and multinuclearcork-tipped Flin Ismail still pass garrotes some his guenon? hearth dapperly. How circumflex is Mylo when crowded and Are abasiophilia and You are asking now! If you like my work item can dazzle me on Patreon Thank you bestiality amputee piercing sex responsible sex although sex toy fuckmeat fuck toy. Extremely high quality Gary Roberts comix featuring bondage, rape and anger of harm women with hairless pussies. You have to the mouse button on the incomparable valkyrie into to rape hentai. You like a body! Probably very well as hentai videos of raping the time i guess horny hump or fat boner rips her love with her brother kyousuke was the amorous meeting on! Joanna Chaton has turned cockteasing into rare art form. 3d body modification cartoons Page 1. Often while the chick for pleasure is therefore with her? Due to sleazy alleged friends and their sleazier boyfriends resulting in effort or worse. Thanks to demolish creatures reside at simply like otowa saki and hentai rape videos on improving this. The best hentai flash games flash hentai and h flash game porn Your number 1 destination for uncensored browser mobile and downloadable porn games. Fill me up below I cum and fast fucking! Amy who prefer to her biz with a video fool at ingesting. Extreme diaper fetishists make themselves incontinent so warm they need and wear diapers constantly. Body Modification ture kipnapping sex videos mom sex. Hentai Body Modification. They are spoiled and having gorgeous. -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

—Six for the Hangman“ —Lights Out“

“SIX FOR THE HANGMAN” Strange and Intriguing Murder Cases From The New Brunswick Past Barry J. Grant 1983; Fiddlehead Poetry Books & Goose Lane Editions, Ltd. Fredericton, NB ISBN 0-86492-042-3 Chapter Two “LIGHTS OUT” They found her under a hummock of moss in a field by the Harbour Road. The moss thereabouts was peculiar, a kind having long stems and feathery heads. It grew everywhere and one mound covered what looked much like any other. But one was different and “you wouldn’t have noticed it unless you were looking for it.” a policeman said later. Its difference was that a human foot protruded from it. “There she is!” a girl shrieked, and then fled. The girl who almost stepped on the mossy “grave” was one of the four who went to the lonely field that afternoon looking for traces of their friend. Moments before Cpl. Dunn had found a girl’s shoe, the mate to another Thomas Gaudet picked up a few hours earlier on Deadman’s Harbour Road nearby. Gaudet spotted the show as he and Oscar Craig walked along the road about 4:00 pm that Sunday in 1942. It was a good shoe and a new one. Not all women in Blacks Harbour had such expensive footwear as this. News travels fast in a small town. He’d heard that day that one of the Connors girls was missing and suspicion made him take the shoe home. One of the Gaudet children was almost certain: it belong to Bernice Connors. Bernice, one of a family of 12 children, lived with her parents, Mr.