—Six for the Hangman“ —Lights Out“

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superhero Therapy Day 1 Slides

Origin Stories Origin Stories • “What I wouldn’t give to be normal” – Mystique and Beast (First Class) Post-Traumatic Growth Superman: Clinical Application • “I wanted to be Superman… I failed” Superman: Clinical Application • “I wanted to be Superman, I failed” • Invincible Superman: Clinical Application • “I wanted to be Superman, I failed” • Invincible • Kryptonite What is Superhero Therapy? Using popular culture (books, TV shows, movies, and video games examples) in evidence-based therapies (CBT, ACT, prosocial research) For “KIDS” of all ages Most Important Rule: • You don’t have to be the expert in pop culture • The client is the expert ! Why Superhero Therapy? • During most difficult times, people feel alone • Shame is a common feature Brene Brown’s Research • “We deny our loneliness. We feel shame around being lonely even when it’s caused by grief, loss, or heartbreak” Brené Brown • Many people suffer from periodic shame – Shame is “under the radar”, difficult to talk about – The less it’s talked about, the more shame compounds • Shame has negative effects – May underlie low mood, low self esteem, alienation – Drives negative behavior, compensatory attention seeking Potential Triggers for Shame Experiences of Not Fitting In related to: • Appearance • Sex (including ”slut-shaming”) • Body Image • Gender identity/sexual orientation • Money • Religion/Cultural identity • Mental health • Surviving/experiencing trauma • Physical health • Race/ethnicity • Addiction • Divorce • Homelessness • Incarceration How shame shows up in mental -

MLJ's Silver Age Revivals

ASK MR. SHUTTSILVER AGE “Too Many Super Heroes” doesn’t really do this group justice MLJ’s Silver Age revivals by CRAIG SHUTT Dear Mr. Silver Age, I’m a big fan of The Fly and Fly Girl, and I understand they were members of a super-hero team. Do you know who else was a member? Betty C. Riverdale Mr. Silver Age says: I sure do, Bets, and you’ll be happy to hear that a few of those stalwart super-heroes are returning to the pages of DC’s comic books. The first to arrive are The Shield, The Web, The Hangman, and Inferno. They’re being touted as the heroes from Archie Comics’ short-lived Red Circle line of the 1980s, but they all got their start much earlier than that, including brief appearances in the Silver Age. During those halcyon days, they all were members of (or at least tried out for) The Mighty Crusaders! And, if the new adventures prove popular, there are plenty more heroes awaiting their own revival. The Mighty Crusaders, Archie’s response to the mid-1960s success of super-hero teams, got their start in Fly Man #31 (May 65). The team consisted of The Shield, Black Hood, The Comet, Fly Man (né The Fly), and Fly Girl. The first three were revived versions of Golden Age characters, while the latter two starred in their own Silver Age series. The heroes teamed up for several issues and then began individual back-up adventures through #39. They also starred in seven issues of Mighty Crusaders starting with #1 (Nov 65) and then took over Fly Man in various combinations, when it became Mighty Comics with #40 (Nov 66). -

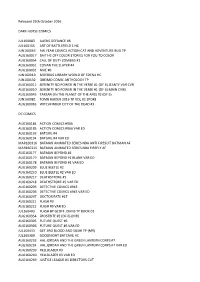

Released 20Th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS

Released 20th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS OCT170039 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 OCT170040 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 VAR AUG170013 BLACK HAMMER TP VOL 02 THE EVENT OCT170019 EMPOWERED & SISTAH SPOOKYS HIGH SCHOOL HELL #1 OCT170021 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 OCT170023 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 HUGHES SKETCH VAR OCT170022 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 MIGNOLA VAR OCT170020 JOE GOLEM OCCULT DET FLESH & BLOOD #1 (OF 2) OCT170061 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) OCT170062 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) FEGREDO VAR OCT170080 TOMB RAIDER SURVIVORS CRUSADE #2 (OF 4) APR170127 WITCHER 3 WILD HUNT FIGURE GERALT URSINE GRANDMASTER DC COMICS OCT170220 AQUAMAN #31 OCT170221 AQUAMAN #31 VAR ED JUL170469 BATGIRL THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 OCT170227 BATMAN #37 OCT170228 BATMAN #37 VAR ED SEP170410 BATMAN ARKHAM JOKERS DAUGHTER TP SEP170399 BATMAN DETECTIVE TP VOL 04 DEUS EX MACHINA (REBIRTH) OCT170213 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) OCT170214 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) VAR ED OCT170233 BATWOMAN #10 OCT170234 BATWOMAN #10 VAR ED OCT170242 BOMBSHELLS UNITED #8 SEP170248 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) SEP170251 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) DANIEL VAR ED SEP170249 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) KUBERT VAR ED SEP170250 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) LEE VAR ED SEP170444 EVERAFTER TP VOL 02 UNSENTIMENTAL EDUCATION OCT170335 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 OCT170336 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 VAR ED OCT170263 GREEN LANTERNS #37 OCT170264 GREEN LANTERNS #37 VAR ED SEP170404 GREEN LANTERNS TP VOL 04 THE FIRST RINGS (REBIRTH) -

Amuse Bouche

CAT-TALES AAMUSE BBOUCHE CAT-TALES AAMUSE BBOUCHE By Chris Dee Edited by David L. COPYRIGHT © 2006 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION AMUSE BOUCHE As hostess for the Iceberg Lounge, Raven made a decent living, but she was still a working girl and vacations were an extravagance. She’d taken the occasional weekend upstate when it turned serious with this guy or that one. And there was a wild bachelorette trip on a train to Savannah with three other bridesmaids before her sister’s wedding. That was really it. She’d never been out of the country before. But the travel agent Oswald sent her to, called Royal Wing Excursions, booked vacation packages for well-traveled Gothamites. Raven said she dreamed of going to Paris, but the City of Lights must have been too familiar to the Royal Wing clients because she only got a day there. Once her plane landed, she got to see the Eiffel Tower, eat in a real French café, and take a cruise down the Seine. Then she had to find her bed & breakfast in Monmarte and, first thing in the morning, catch a special train to a place called Savigny les Beaune where she met up with Florent her guide, her fellow travelers, and a not-too-intimidating bicycle. They set off the next morning for Nuits St. Georges and by the time they arrived at their first vineyard, everyone was on a first name basis. -

Batman: the Brave and the Bold - the Bronze Age Omnibus Vol

BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD - THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS VOL. 1 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bob Haney | 9781401267186 | | | | | Batman: the Brave and the Bold - the Bronze Age Omnibus Vol. 1 1st edition PDF Book Then: Neal Adams. Adventures of Superman —; Superman vol. Also available from:. Batman and his partners sometimes investigate and fight crime outside Gotham, in such locales as South America, the Caribbean, England, Ireland, and Germany. October 8, Adams does interior pencils for 8 stories in this collection as well as numerous covers. Individual volumes tend to focus on collecting either the works of prolific comic creators, like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko ; major comic book events like " Blackest Night " and " Infinite Crisis "; complete series or runs like " Gotham Central " and " Grayson " or chronological reprints of the earliest years of stories featuring the company's most well known series and characters like " Batman " and " Justice League of America ". One-and-done team-up stories, with any characters in their universe. Max Worrall rated it it was amazing May 19, This is not the dark detective but rather the mistake prone guy in a bat suit. I have to bring up his cover for BATB And yet, while stories can be hokey at times, there are some real classics. Getting chewed out by commissioner Gordon for "not solving the cases fast enough! By the mids, it morphed into a team-up series and, starting with issue 74, exclusively a Batman team-up title until its conclusion with issue it later rebooted. Readers also enjoyed. Lists with This Book. -

The Metaphysics of the Hangman

Chapter 4 The Metaphysics of the Hangman Prior to introduction of the electric chair in 1890, hanging was the prin- cipal and, more often than not, the exclusive method of state-sponsored killing in all of the United States (Drimmer 1990). Indeed, of the nearly twenty thousand documented executions conducted since the found- ing of the first permanent English settlement at Jamestown, close to two-thirds have been accomplished by this means (Macdonald 1993). Today, however, this practice stands poised at the brink of extinction. Eliminated by Congress for civilians convicted of federal crimes in 1937 and by the army in 1986, hanging is still prescribed in only four states.1 The members of this quartet have performed a total of three hangings since its revival, following a twenty-eight year hiatus, in 1993. Yet even these states now prescribe lethal injection as their default method of execution; and, in all likelihood, they will retain hanging as an option only so long as it is necessary to foreclose legal challenges by persons sentenced under earlier statutes. In short, the noose is quickly passing into obsolescence and so, like the rack and the gibbet, is destined to van- ish—except perhaps as a curiosity of historical inquiry and museum exhibition. What are we to make of the virtual demise of state-sponsored hangings? To offer a partial response to this question, in this chapter, I explore a neglected dimension of what is arguably the most sustained judicial inquiry into hanging ever conducted in the United States. In February 1994, a bitterly divided eleven-member panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Charles Campbell’s challenge to hanging’s constitutionality (Campbell v. -

Surveillance, Social Order, and Gendered Subversions

SURVEILLANCE, SOCIAL ORDER, AND GENDERED SUBVERSIONS IN BATMAN COMICS, 1986-2011 by © Aidan Diamond (Thesis) submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts Department of English Memorial University of Newfoundland October 2017 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador !ii ABSTRACT Batman is “the world’s most popular superhero.”1 An icon of American excep- tionalism, Batman has been featured in radio programmes, television shows, musicals, and more films than any other superhero since his 1939 comic book inception. While Batman has also been the subject of more scholarship than any other superhero, sustained scholarly inquiry of his vigilante infrastructures and their effects upon those Batman deems criminal is scarce; instead, critical readers prefer to interrogate his fascist under- tones. This thesis aims to ameliorate this lack of scholarship by interrogating Batman’s regulatory surveillance assemblage, particularly how it is negotiated and subverted by Barbara Gordon/Oracle and Selina Kyle/Catwoman. Using Foucault’s theories of crimi- nality, Lyon’s articulation of surveillance, Haraway’s cyborg hybridizations, Mulvey’s deconstruction of the gaze, and Butler’s and Tasker’s respective conceptualizations of gender, I argue that female characters problematize and complicate the otherwise unques- tioned authority of Batman’s surveillance assemblage in the 1986-2011 DC continuity. 1 “Batman Day Returns!” DC Comics. 14 June 2016, www.dccomics.com/blog/2016/06/14/batman-day- returns. Accessed 16 July 2017. !iii Acknowledgements This project owes its existence to a great many people who supported and encour- aged me throughout the process, asked insightful and necessary questions, took the time to read early chapter drafts, let me take the time to pet dogs and read non-Bat-comics, and were just generally the best friends a thesis-writer could hope for. -

The Complete History of Archie Comics' Super

THE COMPANION by Paul Castiglia The Complete History & Rik Offenberger of Archie Comics’ Super-Heroes! FROM THE GOLDEN AGE… THROUGH THE SILVER AGE… INTO THE 1980s… UP TO THE PRESENT DAY! Foreword of Contents Table by Paul Castiglia ..........................................................................................................7 Introduction by Rik Offenberger .....................................................................................................9 The Mighty Heroes of MLJ ...................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: MLJ Heroes in the 1930s and ’40s Publisher Profile: MLJ Comics ............................................................................. 12 All The Way With MLJ! The Saga of the Super-Heroes who Paved the Way for Archie ........................ 15 Interview with Irv Novick .................................................................................... 00 The Black Hood Hits the Airwaves ...................................................................... 00 A Brief History of Canada’s Golden Age Archie Comics ............................... 00 Chapter 2: Mighty Comics in the 1950s and 1960s Those Mighty, Mighty Crusaders: The Rise And Fall— And Rise And Fall And Rise—of Archie’s 1960s Super-Hero Group ........... 00 High-Camp Superheroes Invade Your Local Book Store! ............................... 00 The Mighty Comics Super-Heroes Board Game ............................................... 00 The Shadow’s Forgotten Chapter ......................................................................... -

Released 26Th October 2016

Released 26th October 2016 DARK HORSE COMICS JUL160083 ALIENS DEFIANCE #6 JUL160155 ART OF BATTLEFIELD 1 HC JUN160065 AW YEAH COMICS ACTION CAT AND ADVENTURE BUG TP AUG160017 BAIT HC OFF COLOR STORIES FOR YOU TO COLOR AUG160054 CALL OF DUTY ZOMBIES #1 AUG160051 CONAN THE SLAYER #4 AUG160031 MAE #6 JUN160019 MOEBIUS LIBRARY WORLD OF EDENA HC JUN160132 OREIMO COMIC ANTHOLOGY TP AUG160011 SERENITY NO POWER IN THE VERSE #1 (OF 6) JEANTY VAR CVR AUG160010 SERENITY NO POWER IN THE VERSE #1 (OF 6) MAIN CVRS AUG160045 TARZAN ON THE PLANET OF THE APES #2 (OF 5) JUN160081 TOMB RAIDER 2016 TP VOL 01 SPORE AUG160063 WITCHFINDER CITY OF THE DEAD #3 DC COMICS AUG160184 ACTION COMICS #966 AUG160185 ACTION COMICS #966 VAR ED AUG160193 BATGIRL #4 AUG160194 BATGIRL #4 VAR ED MAR160316 BATMAN ANIMATED SERIES NBA ANTI FIRESUIT BATMAN AF MAR160315 BATMAN ANIMATED SERIES NBA FIREFLY AF AUG160177 BATMAN BEYOND #1 AUG160179 BATMAN BEYOND #1 BLANK VAR ED AUG160178 BATMAN BEYOND #1 VAR ED AUG160209 BLUE BEETLE #2 AUG160210 BLUE BEETLE #2 VAR ED AUG160217 DEATHSTROKE #5 AUG160218 DEATHSTROKE #5 VAR ED AUG160205 DETECTIVE COMICS #943 AUG160206 DETECTIVE COMICS #943 VAR ED AUG160297 DOCTOR FATE #17 AUG160221 FLASH #9 AUG160222 FLASH #9 VAR ED JUL160403 FLASH BY GEOFF JOHNS TP BOOK 03 AUG160354 FROSTBITE #2 (OF 6) (MR) AUG160305 FUTURE QUEST #6 AUG160306 FUTURE QUEST #6 VAR ED JUL160433 GET JIRO BLOOD AND SUSHI TP (MR) JUL160389 GOODNIGHT BATCAVE HC AUG160233 HAL JORDAN AND THE GREEN LANTERN CORPS #7 AUG160234 HAL JORDAN AND THE GREEN LANTERN CORPS #7 VAR ED AUG160239 -

Joe Kubert: How a Comics Legend Built His Remarkable Career

Roy Thomas’Kubert Tribute Comics Fanzine $ No.116 8.95 May In the USA 2013 4 0 JOE 5 3 6 7 KUBERT 7 A GOLDEN & 2 SILVER AGE LEGEND 8 5 REMEMBERED 6 2 8 1 Vol. 3, No. 116 / May 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek Contents William J. Dowlding Writer/Editorial: Just A Guy Called Joe . 2 Cover Artists Joe Kubert: How A Comics Legend Built His Remarkable Career. 3 Daniel James Cox & Joe Kubert Bill Schelly pays tribute to one of the last—and best—of Golden Age artists. With Special Thanks to: “We’re In The Kind Of Business Where The Story Is King” . 11 Heidi Amash Jennifer Hamerlinck Kubert talks to Richard J. Arndt about being an artist, editor, and entrepreneur. Ger Apeldoorn Douglas (Gaff) Jones A Chat With Joe Kubert . 41 Richard J. Arndt Adam Kubert Excerpts from Bill Schelly’s interviews with Kubert for his 2008 biography Man of Rock. Bob Bailey Andy Kubert Behind The Lines With The Enemy Ace . 49 Mike W. Barr Dominique Leonard Rod Beck Alan Light Daniel James Cox queries the artist on the unique Kanigher/Kubert series. John Benson Jim Ludwig A Brief Eulogy For Joe Kubert—Humanitarian . 56 Kevin Brogan Doug Martin Mike Bromberg Bruce Mason Kevin Brogan’s speech posthumously presenting JK the Giordano Humanitarian Award. -

Batman: Dark Victory Free

FREE BATMAN: DARK VICTORY PDF Tim Sale,Jeph Loeb | 400 pages | 25 Feb 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401244019 | English | United States Batman: Dark Victory by Jeph Loeb Batman: Dark Victory. Batman: Dark Victory Review. Does the follow-up to The Long Halloween fall flat on its face? Batman: Dark Victory is a far better book when its predecessor, The Long Halloweenis fresh in the mind. Alone or at least distanced from Batman: Dark Victory Halloween the sequel appears like a slightly less-effective continuation of the original. In some ways, it feels much more like your standard Batman tale, simply for the fact that many of the key players seem to have fallen easily into familiar roles. When considered as the second half of a two-volume set fitting with Two-Face as the central characterwriter Jeph Loeb's brilliance shines through. There is hardly any Bruce Wayne in this book, because Bruce Wayne is slipping away and Batman is taking over. This is Batman: Dark Victory truly noticeable with Long Halloween recently read, because the contrast in the two books is quite stark. Harvey Dent goes away and so does Bruce Wayne. Each man is split in two, but Batman: Dark Victory masked side is far more dominant. The believed identity of the holiday killer from the first book never sat well with Batman and so when a new spree of holiday-theme murders begin, the Dark Knight suddenly has two cases to solve. First Batman: Dark Victory must figure out who is killing police officers connected with Harvey Dent and why and then attempt to uncover the true identity of Holiday or at least confirm the original findings. -

Representation and Agency of Aging Superheroes in Popular Culture and Contemporary Society

societies Article Representation and Agency of Aging Superheroes in Popular Culture and Contemporary Society KateˇrinaValentová Department of English and Linguistics, Faculty of Arts, University of Lleida, 25003 Lleida, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: The figure of the superhero has always been regarded as an iconic representative of American society. Since the birth of the first superhero, it has been shaped by the most important historical, political, and social events, which were echoed in different comic issues. In principle, in the superhero genre, there has never been a place for aging superheroes, for they stand as a symbol of power and protection for the nation. Indeed, their mythical portrayal of young and strong broad-chested men with superpowers cannot be shattered showing them fragile or disabled. The aim of this article is to delve into the complex paradigm of the passage of time in comics and to analyze one of the most famous superheroes of all times, Superman, in terms of his archetypical representation across time. From the perspective of cultural and literary gerontology, the different issues of Action Comics will be examined, as well as an alternative graphic novel Kingdom Come (2008) by Mark Waid and Alex Ross, where Superman appears as an aged man. Although it breaks the standards of the genre, in the end it does not succeed to challenge the many stereotypes embedded in society in regard to aging, associated with physical, cognitive, and emotional decline. Furthermore, this article will show how a symbolic use of the monomythical representation of a superhero may penetrate into other cultural expressions to instill a more positive and realistic portrayal of aging.