Annual Report 2020. Chapter IV.B Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

New Castro Same Cuba

New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-562-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2009 1-56432-562-8 New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 7 II. Illustrative Cases ......................................................................................................................... 11 Ramón Velásquez -

Calle Con Ángel Gonistas De Varias Actividades Que Galiano

P. 4 capitalinas síganos en: El regreso de Cristina www.tribuna.cu Tribuna de deportes la Habana P. 6 La Habana ante duro reto @TribunaHabana P. 8 Uno por dos escríbanos a: [email protected] 3 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2019 | AÑO 61 DE LA REVOLUCIÓN | ÓRGANO DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO | No. 45 | AÑO XXXIX | ISSN 0864-1609 | CIERRE: 7:00 p.m. | 20 ¢ Habana, 500 razones para celebrarte POR: CHELSEA DEL SOL Y MARCIA RIOS FOTO: JOYME CUAN En la noche de hoy, 3 de noviem- bre, tendrá lugar la clausura del i Habana, se acerca el día. Festival Internacional de la Músi- Pasan las horas y te ves más ca HABANA + en La Piragua. La Mcoqueta, engalanando tus Feria Internacional de La Habana calles con los sueños de quienes –Fihav–, dará inicio en la mañana del nos sentimos tuyos. Se acerca el día lunes 4 de noviembre en su sede ha- y parece mentira, los años han pa- bitual del recinto ferial de Expocuba. sado con tanta prisa que solo que- Cuando el reloj marque las 9:00 da mirarte con nostalgia cautiva- p.m. del próximo 5 de noviembre, dora y sentirnos parte indisoluble en el Castillo de la Real Fuerza, el de tu crecimiento. Palacio de los Capitanes Genera- Se acerca el día y aparecen los les, la Plaza de Armas y la Forta- nervios, las ansias de vivir tu me- leza Morro-Cabaña, se inaugura- dio milenio de existencia y de en- rá la iluminación monumental de tender cuán afortunados somos de esos sitios emblemáticos. -

Travel Weekly Secaucus, New Jersey 29 October 2019

Travel Weekly Secaucus, New Jersey 29 October 2019 Latest Cuba restrictions force tour operators to adjust By Robert Silk A tour group in Havana. Photo Credit: Action Sports/Shutterstock The Trump administrations decision to ban commercial flights from the U.S. to Cub an destinations other than Havana could cause complications for tour operators. However, where needed, operators will have the option to use charter flights as an alternative. The latest restrictions, which take effect during the second week of December, will put an end to daily American Airlines flights from Miami to the Cuban cities of Camaguey, Hoguin, Santa Clara, Santiago and Varadero. JetBlue will end flights from Fort Lauderdale to Camaguey, Holguin and Santa Clara. In a letter requesting the Department of Transportation to issue the new rules, secretary of state Mike Pompeo wrote that the purpose of restrictions is to strengthen the economic consequences of the Cuban governments "ongoing repression of the Cuban people and its support for Nicholas Maduro in Venezuela." The restrictions dont directly affect all Cuba tour operators. For example, Cuba Candela flies its clients in and out of Havana only, said CEO Chad Olin. But the new rules will force sister tour operators InsightCuba and Friendly Planet to make adjustments, said InsightCuba president Tom Popper. In the past few months, he explained, Friendly Planet’s "Captivating Cuba" tour and InsightCubas "Classic Cuba" tour began departing Cuba from the north central city of Santa Clara. Now those itineraries will go back to using departure flights from Havana. As a result, guests will leave Cienfuegos on the last day of the tour to head back to Havana for the return flight. -

A Contemporary Cuba Reader

07-417_00_FM.qxd 7/14/07 11:54 AM Page iii A Contemporary Cuba Reader Reinventing the Revolution Edited by Phillip Brenner, John M. Kirk, William M. LeoGrande, and Marguerite Rose Jiménez ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 07-417_00_FM.qxd 7/14/07 11:54 AM Page iv ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2008 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A contemporary Cuba reader : reinventing the Revolution / edited by Phillip Brenner ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5506-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7425-5506-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5507-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7425-5507-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cuba—History—1990– I. Brenner, Philip. F1788.C67 2008 972.9106'4—dc22 2007017602 Printed in the United States of America. ϱ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

INTERNET 31 DE MARZO.Indd

Síganos en: http://www.tribuna.cu @TribunaHabana ÓRGANO DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO Tribuna de la Habana LA HABANA 31 DE MARZO 2019 / AÑO 61 DE LA REVOLUCIÓN No. 14 / ISSN 0864-1609 / AÑO XXXVII / CIERRE. 7:00 p.m. / 20 CTVOS. Por una economía a la altura del 500 Reinaldo García Zapata, también miembro del Comité Central y presi- dente del Gobierno en la capital, desta- Labores de sustitución de la conductora có la importancia de recaudar lo com- de agua en Palatino-Avenida del Puerto. prometido con las obras del 500 y “ser capaces de captar los millones de ingre- sos de la contribución territorial”. Una actualización de los progra- mas y tareas principales vinculadas al Aniversario 500 de la ciudad, ofreció Luis Carlos Góngora, vicepresidente del Gobierno en la ciudad, quien dio a conocer el inicio de los trabajos en la calle Línea y la conductora Palati- insistir en la disciplina informativa la urgencia de multiplicar la producción no-Avenida del Puerto, la cual bene- A como base del control, el cumpli- de alimentos y aprovechar al máximo los ficiará a más de 150 000 personas, así miento del plan de circulación mercan- recursos disponibles, son algunos de los como el reemplazo de luminarias de til, fomentar las exportaciones y a la vo- retos de La Habana para tener una eco- sodio por led en 64 avenidas. Llamó a Silvio, el primero nomía a la altura de su medio milenio. luntad de sustituir importaciones desde acelerar las obras con atrasos: Jardines los municipios, llamó Luis Antonio To- Iríbar se refirió a tomar el Aniversario de La Tropical, tiendas como Varieda- rres Iríbar, miembro del Comité Central 500 como pretexto para hacer más, a lo des Obispo, Flogar y Bazar Inglés; La por los 500 y primer secretario del Partido en la ca- largo del año, y elevar la exigencia sobre Macumba, de Palmares; la Tienda del pital al analizar el desempeño económi- la contribución territorial como fuen- urante el concierto cien de su gira por los te de desarrollo de los municipios, así mueble y la heladería de 25 y 12, de co de La Habana. -

Chamaeleolis” Species Group from Eastern Cuba

Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem. 76: 45–52, 2012 ISSN 1211-376X Anolis sierramaestrae sp. nov. (Squamata: Polychrotidae) of the “chamaeleolis” species group from Eastern Cuba Veronika Holáňová1,3), Ivan REHÁK2) & Daniel FRYNTA1) 1) Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Viničná 7, CZ–128 43 Praha 2, Czech Republic 2) Prague Zoo, U Trojského zámku 3, CZ–171 00 Praha 7, Czech Republic 3) Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Received 10 February 2012; accepted 16 April 2012 Published 15 August 2012 Abstract. A new species of anole, Anolis sierramaestrae sp. nov., belonging to the “chamaeleolis” species group of the family Polychrotidae, is described from the mountain region in the vicinity of La Mula village, Santiago de Cuba province, Cuba. The species represents the sixth so far known species of the “chamaeleolis” species group. It resembles Anolis chamaeleonides Duméril et Bibron, 1837, but differs markedly in larger body size, long and narrow head shape, higher number of barb-like scales on dewlap, small number of large lateral scales on the body and dark-blue coloration of the eyes. Key words. Taxonomy, new species, herpetofauna, Polychrotidae, Chamaeleolis, Anolis, Great Antilles, Caribbean, Neotropical region. INTRODUCTION False chameleons of the genus Anolis Daudin, 1802 represent a highly ecologically specialized and morphologically distinct and unique clade endemic to Cuba Island (Cocteau 1838, Beuttell & Losos 1999, Schettino 2003, Losos 2009). This group has been traditionally recognized as a distinct genus Chamaeleolis Cocteau, 1838 due to its multiple derived morphological, eco- logical and behavioural characters. Recent studies discovering the cladogenesis of anoles have placed this group within the main body of the tree of Antillean anoles as a sister group of a small clade consisting of the Puerto Rican species Anolis cuvieri Merrem, 1820 and hispaniolan A. -

El Arte Bajo Presion

Artists at Risk Connection El Arte Bajo Presión EL DECRETO 349 RESTRINGE LA LIBERTAD DE CREACIÓN EN CUBA 1 EL ARTE BAJO PRESIÓN El Decreto 349 restringe la libertad de creación en Cuba 4 de marzo de 2019 © 2019 Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) y Cubalex. Todos los derechos reservados. Artists at Risk Connection (ARC), un proyecto de PEN America, es responsable de la coordinación e intercambio de información de una red que apoya, une y avanza el trabajo de las organizaciones que asisten a artistas en riesgo en todo el mundo. La misión de ARC es mejorar el acceso de artistas en riesgo a recursos, facilitar las conexiones entre los que apoyan la libertad artística y elevar el perfil de los artistas en riesgo. Para obtener más información, visite: artistsatrisk- connection.org. Cubalex es una organización sin fines de lucro cuya labor se enfoca en temas legales en Cuba. Fue fundada el 10 de dic- iembre de 2010 en La Habana y ha sido registrada como una organización caritativa en los Estados Unidos desde junio de 2017, después de que la mayoría de su personal fuera obligado a exiliarse. La misión de Cubalex es proteger y promover los derechos humanos para producir una transformación social que permita el restablecimiento de la democracia y el estado de derecho en Cuba. Para obtener más información, visite centrocubalex.com. Autoras: Laritza Diversent, Laura Kauer García, Andra Matei y Julie Trébault Traducción hecha por Hugo Arruda Diseño por Pettypiece + Co. Imagen de portada por Nonardo Perea ARC es un proyecto de PEN America. -

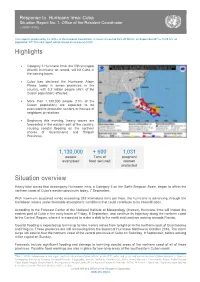

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Internet Diffusion and Adoption in Cuba Randi L

Atlantic Marketing Journal Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 6 2016 Internet Diffusion and Adoption in Cuba Randi L. Priluck Pace University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, Communication Commons, E- Commerce Commons, Marketing Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, and the Other Business Commons Recommended Citation Priluck, Randi L. (2016) "Internet Diffusion and Adoption in Cuba," Atlantic Marketing Journal: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Atlantic Marketing Journal by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Internet Diffusion and Adoption in Cuba Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine Internet adoption at a time of increasing change for the Cuban marketplace. As the Cuban economy begins to open to new business formats one key driver of economic growth will be access to communications networks. This paper explores the penetration of Internet connectivity in Cuba as relations with the United States thaw. The theories of diffusion of innovations, cultural dimensions of adoption and market and political realities are employed to better understand the pace of Internet adoption as the Cuban economy continues to develop. Keywords: Cuba, Internet Adoption, Emerging Economy, Marketing Introduction Cuba is one of the last countries in the world to provide online access for its citizens in spite of the economic advantages that connectivity brings to economies.