An Account of Ts'kw'aylaxw Philosophy and Use of Water in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1996 Annual Report

203 –1155 W. Pender St. Vancouver B.C. V6E 2P4 604 482 9200, Fax 604 482 9222 [email protected]. www.bctreaty.net Annual Report 1996 Introduction The British Columbia Treaty Commission was appointed on April 15, 1993 under terms of an agreement between the Government of Canada, the Government of British Columbia and the First Nations Summit, whose members represent the majority of the First Nations in British Columbia. The terms of agreement require the Commission to submit annually to the Parliament of Canada, the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia and the First Nations Summit "a report on the progress of negotiations and an evaluation of the process." The annual financial data has been prepared to coincide with the fiscal year-end of the Governments of Canada and British Columbia and is submitted as a separate document. It is my pleasure to submit the third Annual Report of the British Columbia Treaty Commission. As Chief Commissioner, I wish to express my thanks to my fellow Commissioners, and to the men and women who comprise the Commission's staff, for their hard work, commitment and support. Alec Robertson, Q.C. Chief Commissioner 203 –1155 W. Pender St. Vancouver B.C. V6E 2P4 604 482 9200, Fax 604 482 9222 [email protected]. www.bctreaty.net Annual Report 1996 Executive Summary As the independent and impartial keeper of the process, the British Columbia Treaty Commission is pleased to report that significant progress has been made over the past year in those treaty negotiations which it facilitates. There are 22 First Nations tables in Stage 3 framework negotiations and 11 in Stage 4, agreement in principle negotiations. -

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expension Project

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project November 2016 Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms, Abbreviations and Definitions Used in This Report ...................... xi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ..............................................................................1 1.2 Project Description .................................................................................2 1.3 Regulatory Review Including the Environmental Assessment Process .....................7 1.3.1 NEB REGULATORY REVIEW AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ....................7 1.3.2 BRITISH COLUMBIA’S ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................8 1.4 NEB Recommendation Report.....................................................................9 2. APPROACH TO CONSULTING ABORIGINAL GROUPS ........................... 12 2.1 Identification of Aboriginal Groups ............................................................. 12 2.2 Information Sources .............................................................................. 19 2.3 Consultation With Aboriginal Groups ........................................................... 20 2.3.1 PRINCIPLES INVOLVED IN ESTABLISHING THE DEPTH OF DUTY TO CONSULT AND IDENTIFYING THE EXTENT OF ACCOMMODATION ........................................ 24 2.3.2 PRELIMINARY -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

Board of Directors Regular - 15 Aug 2019 - Minutes DRAFT

THOMPSON-NICOLA REGIONAL DISTRICT Regular Meeting – THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 A G E N D A Time: 1:15 PM Place: Board Room 4th Floor 465 Victoria Street Kamloops, BC Page 1 CALL TO ORDER 2 PUBLIC HEARINGS (If Required) 3 CHAIR'S ANNOUNCEMENTS 4 ADDITIONS TO OR DELETIONS FROM THE AGENDA 5 MINUTES 11 - 25 5.a 2019 August 15 Regular Board Meeting Minutes DRAFT Attachments: Board of Directors Regular - 15 Aug 2019 - Minutes DRAFT RECOMMENDATION: THAT the minutes of the August 15, 2019 Regular Board Meeting be adopted. 26 - 27 5.b 2019 August 15 Record of Thompson-Nicola Regional District Public Hearing Zoning Bylaw Amendment No. 2685, 2019 Zoning Amendment No. BA 177 Attachments: Public Hearing BA177 - 15 Aug 2019 - Minutes DRAFT RECOMMENDATION: THAT the Record of August 15, 2019 Public Hearing on Zoning Bylaw Amendment No. 2685, 2019, Zoning Amendment No. BA 177, be accepted as recorded. Agenda – Board of Directors Regular Meeting Thursday, September 19, 2019 28 - 29 5.c 2019 August 15 Record of Thompson-Nicola Regional District Public Hearing Cherry Creek - Savona OCP Amendment Bylaw No. 2688, 2019 Zoning Amendment Bylaw No. 2689, 2019, Application No. BA 178 Attachments: Public Hearing BA178 - 15 Aug 2019 - Minutes DRAFT RECOMMENDATION: THAT the Record of August 15, 2019 Public Hearing on Cherry Creek - Savona OCP Amendment Bylaw No. 2688, 2019, Zoning Amendment Bylaw No. 2689, 2019, Application No. BA 178 be accepted as recorded. 6 BYLAWS (From Public Hearing - If Required) 7 DELEGATIONS 30 - 68 7.a Tourism and Destination Development Strategy Update Cariboo Chilcotin Coast Tourism Association Jolene Lammers, Destination Development Coordinator Attachments: Cariboo-Chilcotin Coast Tourism Association Request for Letter of Support 7.b Roadside Weed Control Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Graham Gielens, Manager, Roadside Development 8 UNFINISHED BUSINESS 69 - 76 8.a Financial Request - 2019 BC Agricultural Exhibition Evelyn Pilatzke, President BC Agricultural Exhibition Society Report by the Director of Finance dated August 16, 2019. -

TMX Consultation Reference: Ts'kw'aylaxw (Pavillion Indian Band)

Appendix B.26 - Ts'kw'aylaxw First Nation (Pavilion Indian Band) I - Background Information Ts'kw'aylaxw First Nation (Ts’kw’aylaxw) (pronounced “TS-KWHY-lux”), also known as Pavilion Indian Band, is located in the south central interior of British Columbia (BC), approximately 40 kilometres (km) northwest of Lillooet and 70 km west of Cache Creek. The Ts’kw’aylaxw is a Secwepemc (pronounced “Shi-HUEP-muh” or “She-KWE-pem”) (Shuswap) group, historically part of the ethnographic “Bonaparte Division” and over time, through intermarriage, the Ts'kw'aylaxw were absorbed by the St’at’imc (Lillooet) Nations, specifically associated with the Fraser River Band (šλáλimx?úl) of the upper division of the St'at'imc. The Ts’kw’aylaxw are a member of the St'át'imc Chiefs Council. Ts'kw'aylaxw has eight reserves: Leon Creek no.2 (472.5 hectares [ha]), Leon Creek no.2A (176.4 ha), Marble Canyon no.3 (263.1 ha), Pavilion no.1 (881.2 ha), Pavilion no.1A (16.2 ha), Pavilion no.3A (256.2 ha), Pavilion no.4 (45.3 ha), and Ts’kw’aylaxw no.5 (16.1 ha) but resides on only four of the reserves. Ts'kw'aylaxw has a total registered population of 567 (197 [35%] are living on their reserve, 77 [14%] are living on other reserves, and 293 [52%] are living off reserve). The closest community/reserve is located 85 km away from the pipeline right of way (RoW). Ts'kw'aylaxw submitted a Statement of Intent (SOI) to the BC Treaty Commission (BCTC) on October 11, 1994. -

Tribal Case Book - Secwepemc Stories and Legal Traditions Stsmémelt Project Tek’Wémiple7 Research

Tribal Case Book - Secwepemc Stories and Legal Traditions Stsmémelt Project Tek’wémiple7 Research Created by: Kelly Connor, B.A. (Hons), M.A. Researcher 2/7/2013 Table of Contents 1.0 Background........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Secwepemc Overview...................................................................................................1 1.2 Stsmémelt Tek’wémiple7 Overview.......................................................................4 1.3 Pillars of Jurisdiction.....................................................................................................5 1.4 Seven Sacred Laws.........................................................................................................6 2.0 Research Methods............................................................................................................7 2.1 Purpose................................................................................................................................7 2.2 Rationale.............................................................................................................................7 2.2.1 Indigenous Legal Traditions................................................................7 2.2.2 Why Stories?...............................................................................................8 2.2.3 Legal Analysis and Synthesis Methodology..................................9 2.3 Activities...........................................................................................................................10 -

Contamination Identification and Assessment Plan for the Trans Mountain Pipeline Ulc Trans Mountain Expansion Project Neb Condition 46

CONTAMINATION IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT PLAN FOR THE TRANS MOUNTAIN PIPELINE ULC TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT NEB CONDITION 46 August 2017 REV 4 687945 01-13283-GG-0000-CHE-RPT-0036 R4 DRAFT for Review Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Kinder Morgan Canada Inc. Suite 2700, 300 – 5th Avenue S.W. Calgary, Alberta T2P 5J2 Ph: 403-514-6400 Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Contamination Identification and Assessment Plan Trans Mountain Expansion Project 687945/August 2017 TABLE OF CONCORDANCE National Energy Board (NEB) Condition 46 is applicable to the following legal instruments: OC-064 (CPCN), AO-003-OC-2 (OC2), AO-002-OC-49 (OC49), XO-T260-007-2016 (Temp), XO-T260-008-2016 (Pump 1), XO-T260-009-2016 (Pump 2), XO-T260-010-2016 (Tanks) and MO-015-2016 (Deact). Table 1 describes how this Plan addresses the Condition requirements applicable to Project activities. TABLE 1 LEGAL INSTRUMENT CONCORDANCE WITH NEB CONDITION 46: CONTAMINATION IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT PLAN OC-064 AO-003-OC-2 (OC2) AO-002-OC-49 XO-T260-007-2016 XO-T260-008-2016 XO-T260-009-2016 XO-T260-010-2016 MO-015_2016 NEB Condition 46 (CPCN) (OC49) (Temp) (Pump1) (Pump2) (Tanks) (Deact) Trans Mountain must file with the NEB for approval, at least 4 months prior to Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan Sections 4.0 and 5.0 of this Plan commencing construction, a Contamination Identification -

RIGHTS in BRITISHCOLUMBIA a Historical Summary of the Rz&Ht.Sof the Pavibon First Nation

FIRSTNATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISHCOLUMBIA A Historical Summary of the rz&ht.sof the Pavibon First Nation Management and Standards Branch Copy NOT TO BE REMOVED FROM THE OFFICE BRITISH Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks COLUMBIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, LANDS, AND PARKS WATER MANAGEMENT BRANCH FIRST NATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: A Historical Summary of the rigkts of tke Pavilion First Nation Prepared by: Gary W. Robinson Daniela Mops Edited by: Diana Jolly and Miranda Griffith Reviewed by: Gary W. Robinson February 18,1997 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Robinson, G. (Gary), 1949- First Nations water rights in British Columbia. A historical summary of the rights of the Pavilion First Nation ISBN 0-7726-3364-9 1. Water rights - British Columbia - Pavilion Indian Reserve No. 1. 2. Water rights - British Columbia - Pavilion Indian Reserve No. 1A. 3. Water rights - British Columbia - Leon Creek Indian Reserve No. 2. 4. Water rights - British Columbia - Marble Canyon Indian Reserve No. 3. I. Mogus, Daniela. 11. Jolly, Diana. 111. Griffith, Miranda. IV. BC Environment. Water Management Branch. V. Title. VI. Title: Historical summary of the rights of the Pavilion First Nation. KEB529.5 .W3R62 ,1997 346.71104’32 C97-960262-9 KF8210.W38R62 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks wishes to acknowledge three partners whose contributions were invaluable in the completion of the Aboriginal Water Rights Report Series: The Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, was a critical source of funding, support and direction for this project. The U-Vic Geography Co-op Program, was instrumental in providing the staffing resources needed to undertake this challenging task. -

Trans Mountain Attachment 1 Condition 43

Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Watercourse Crossing Inventory Trans Mountain Expansion Project March 2017 APPENDIX L ABORIGINAL GROUPS TO BE ENGAGED ON NEB CONDITION 43: WATERCOURSE CROSSING INVENTORY Adams Lake Indian Band Aitchelitz First Nation (Stó:lō) Alexander First Nation Alexis Nakota Sioux First Nation Aseniwuche Winewak Nation Ashcroft Indian Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Asini Wachi Nehiyawak Boothroyd Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Boston Bar Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) British Columbia Métis Federation Canim Lake Band (Tsq’escen') Canoe Creek (Stswecem'c Xgat'tem) Indian Band Chawathil First Nation (Stó:lō) Cheam First Nation (Stó:lō) Clinton Indian Band/Whispering Pines First Nation Coldwater Indian Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Cook’s Ferry Indian Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Enoch Cree Nation Ermineskin Cree Nation Foothills Ojibway Society High Bar Horse Lake First Nation (Treaty 8) Kanaka Bar Katzie First Nation Kelly Lake Cree Nation Kelly Lake First Nation Kelly Lake Métis Settlement Society Ktunaxa Nation Kwantlen First Nation (Stó:lō) Kwaw-kwaw-Apilt First Nation (Stó:lō) Kwikwetlem First Nation Leq’a:mel First Nation (Stó:lō) Lheidli T’enneh First Nation Lhtako Dene Nation Little Shuswap Indian Band Louis Bull Tribe Lower Nicola Indian Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Lower Similkameen Indian Band Lyackson First Nation Lytton First Nation (Nlaka’pamux Nation) Matsqui First Nation (Stó:lō) Métis Nation of Alberta Gunn Métis Local 55 Métis Nation of British Columbia Métis Regional Council Zone IV of -

B.C. First Nations Pronunciation Guide

A Guide to the Pronunciation of Indigenous Communities and Organizations in BC The Pronunciation Guide offered below is from the September 2018 Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia. Please note there may be some variation from this version due to periodic updates that have occurred since then. For changes, please email: [email protected]. This Guide contains aids to the pronunciation of communities and organizations listed in the Excel Database “Guide to Indigenous Organizations and Services in British Columbia” (Previously known as The Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia). The original Pronunciation Guide was created with input from First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, as well as from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council. British Columbia has a vast wealth of First Nations languages and cultures. There are 7 distinct language families, completely unrelated to each other. Within these families there are 34 different First Nations languages and at least 93 different dialects (varieties) of those languages. Besides these 34 living languages, at least three languages which were spoken in British Columbia are now sleeping.1 All of these languages contain a rich inventory of sounds, many of which are not found in English. When preparing this Guide, we asked representatives to help us understand how to pronounce the traditional name of their community or organization. The pronunciation equivalents we have developed here are meant as an introductory guide. The final authority on a pronunciation rests with the community. We encourage you to gain a first-hand understanding of how a name is pronounced by speaking directly with, and being guided by, representatives from each community. -

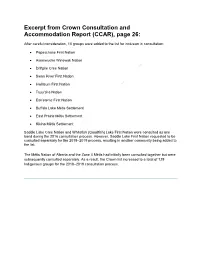

Excerpt from Crown Consultation and Accommodation Report (CCAR), Page 26

Excerpt from Crown Consultation and Accommodation Report (CCAR), page 26: After careful consideration, 10 groups were added to the list for inclusion in consultation: Papaschase First Nation Aseniwuche Winewak Nation Driftpile Cree Nation Swan River First Nation Hwlitsum First Nation Tsuu’tina Nation Esk’etemc First Nation Buffalo Lake Métis Settlement East Prairie Métis Settlement Kikino Métis Settlement Saddle Lake Cree Nation and Whitefish (Goodfish) Lake First Nation were consulted as one band during the 2016 consultation process. However, Saddle Lake First Nation requested to be consulted separately for the 2018–2019 process, resulting in another community being added to the list. The Métis Nation of Alberta and the Zone 4 Métis had initially been consulted together but were subsequently consulted separately. As a result, the Crown list increased to a total of 129 Indigenous groups for the 2018–2019 consultation process. Annex A – List of Eligible Communities 2019 Western Approach Ditidaht First Nation Huu-ay-aht First Nations Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h First Nations Pacheedaht First Nation Toquaht Nation Uchucklesaht Tribe Ucluelet First Nation Vancouver Island - South Esquimalt Nation Malahat Nation Pauquachin First Nation Scia’new (Beecher Bay) Indian Band Songhees (Lekwungen) Nation Tsartlip First Nation Tsawout First Nation Tseycum First Nation T’Sou-ke First Nation Southeastern Vancouver Island Cowichan Tribes Halalt First Nation Hwlitsum First Nation Lake Cowichan First Nation Lyackson First Nation Penelakut -

Community Economic Development Projects

COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 02 December 2014 Prepared for: Northern Economic Development and Initiatives Committee Squamish-Lillooet Regional District c/o District of Lillooet PO Box 610 615 Main Street Lillooet BC V0K 1V0 Prepared by: Fraser Basin Council www.fraserbasin.bc.ca Contact: Mike Simpson, MA, RPF Senior Regional Manager, Thompson 200A - 1383 McGill Road Kamloops BC V2C 6K7 T: (250) 314-9660 [email protected] 1 Executive Summary The Fraser Basin Council (FBC) is under contract with the NEDI Committee, made up of representatives from the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District and the District of Lillooet to conduct four economic development projects including: 1. Project A: Governance Model Feasibility Study for Shared Service Delivery 2. Project B: Community Visioning 3. Project C: Community Asset Inventory 4. Project D: Economic Leakage Analysis Project A – Governance Model Feasibility Study for Shared Service Delivery The feasibility study included conducting a literature review and interviews with other regions that have similar attributes to that of the northern SLRD. The literature along with the interviews revealed similar results, primarily the need for relationships and communication between all of the groups involved in an economic development shared service. The Fraser Basin Council recommends that an economic development steering committee be formed to guide the direction of a shared economic development service with representation from all of the parties involved across the sub-region. During the first year, the development and implementation of the service should be facilitated by a third party, non-profit society. Once the committee membership and service have been established, the committee may form a new non-profit society/join an existing one and hire a staff person to carry out the work, or continue to utilize a third party.