IPSACM),(IPSACM), Saleh Omar, Phd & Adamu Ahmed 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulatory Framework and the Nigeria Tourism Economy

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume IV, Issue XII, December 2020|ISSN 2454-6186 Regulatory Framework and the Nigeria Tourism Economy Yekinni Ojo BELLO, PhD1, Mercy Busayo BELLO2 1University of Port Harcourt, Faculty of Management Sciences, Department of Hospitality Management and Tourism Choba, Rivers State, Nigeria 2Federal Polytechnic Auchi, School of Applied Sciences, Department of Hospitality Management Auchi, Edo State, Nigeria. Abstract: Purpose- This paper examines the extent feasible competitively compared to other countries in Africa (Bello, tourism regulatory framework can contribute to unlocking 2018). It was reported that Sub-Saharan Africa attracted 36 Nigeria tourism economy. million out of 54 million (67%) international tourists that Research Methodology- The study been an exploratory study, visited Africa in 2017 and earned USD$ 25 million put at 74% reviewed various reports and previous literature in this domain of the total tourist receipts in Africa (UNWTO, 2018). This of study upon which insightful inferences were made. seems to be an attractive performance compared to African Findings- The study finds that Nigeria can only maximise her region performance generally. However, tourist arrival in tourism economy potentials if tourism regulatory framework Nigeria in the year under review is below expectation as gear towards environmental sustainability, a secure and safe report has it that Nigeria is lagging far behind South Africa Nigeria, prioritisation of the tourism sector, and promotion of that attracted 8,904 million international tourists, Zimbabwe health and sanitary practices are galvanized. (2,057 million), Mozambique (1,552 million), Mauritania (1,152 million), Kenya (1,114 million), and Cape Verde (520 Research Implications– By establishing five major areas of tourism regulatory framework, the study offers an insight on the Million) (UNWTO, 2018). -

Politics in Nigeria: a Discourse of Osita Ezenwanebe’S ‘Giddy Festival’

Humanitatis Theoreticus Journal, Vol. 1(1) (2018) (Original paper) O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Theatre Politics in Nigeria: A Discourse of Osita Ezenwanebe’s ‘Giddy Festival’ Philip Peter Akoje Department of Theatre Arts, Kogi State University, Ayigba. Email: [email protected] Phone Number: +2347039781766 Abstract Politics is a vital aspect of every society. This is due to the fact that the general development of any country is first measured by its level of political development. Good political condition in a nation is a sine qua non to economic growth. A corrupt and unstable political system in any country would have a domino-effect on the country's economic outlook and social lives of the people. The concept of politics itself continued to be interpreted by many political scholars, critics and the masses from different perspectives. Corruption, political assassination, greed, perpetrated not only by politicians but also by the masses are the societal ills that continue to militate against socio-economic and political development in most African countries, particularly Nigeria. Peaceful political transition to the opposition party in Nigeria in recent times has given a different dimension to the country’s political position for other countries in the region to emulate. This paper addresses the concept of politics and presents corruption in Nigerian society from the point of theatre, using Osita Ezenwanebe’s Giddy Festival. The investigation is grounded in sociological theory and the concept of political realism. This paper recommends that politics can be violent-free if all the actors in the game develop selfless qualities of leadership for the benefit of the ruled. -

Jumia Technologies AG (Translation of Registrant’S Name Into English)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 6-K REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER PURSUANT TO RULE 13a-16 OR 15d-16 UNDER THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the month of: February 2020 Commission File Number: 001-38863 Jumia Technologies AG (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Charlottenstraße 4 10969 Berlin, Germany +49 (30) 398 20 34 51 (Address of principal executive offices) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F. Form 20-F ☒ Form 40-F ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(1): ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(7): ☐ On February 25, 2020, Jumia Technologies AG will hold a conference call regarding its unaudited financial results for the fourth quarter and year ended December 31, 2019. A copy of the related press release is furnished as Exhibit 99.1 hereto. EXHIBIT INDEX Exhibit No. Description of Exhibit 99.1 Press release of Jumia Technologies AG dated February 25, 2020. SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized. Jumia Technologies AG By /s/ Sacha Poignonnec Name: Sacha Poignonnec Title: Co-Chief Executive Officer and Member of the Management Board Date: February 25, 2020 Exhibit 99.1 Jumia reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2019 Results Gross profit up 64% in Q4 2019 year-over-year and 72% for the full year 2019 JumiaPay Transactions accelerate 110% in Q4 2019 year-over-year and 278% for the full year 2019 Lagos, February 25, 2020 – Jumia Technologies AG (NYSE: JMIA) (“Jumia” or the Company) announced today its financial results for the fourth quarter and full-year ended December 31, 2019. -

Mémoire De Fin De Cycle

UNIVERSITE MOULOUD MAMMERI DE TIZI-OUZOU FACULTE DES SCIENCES ECONOMIQUES, COMMERCIALES ET DES SCIENCES DE GESTION DEPARTEMENT DES SCIENCES DE GESTION Mémoire de fin de cycle En vue de l’obtention du Diplôme de Master en Sciences de Gestion Spécialité : Management stratégique Sujet Influence du marketing mobile sur le comportement d’achat du consommateur : cas de la boutique en ligne Jumia Algérie Présenté par : Encadré par : BELKALEM Linda Mme KISSOUM. SISALAH Karima ADJAOUD Djaouida Devant les membres du jury : Présidente: Mme HAMOUTENE Ourdia M.A.A. à UMMTO. Examinatrice : Mme SI MANSOUR Farida M.A.A. à UMMTO. Encadreur : Mme SI SALAH Karima M.A.A. à UMMTO. Promotion 2017/2018 REMERCIEMENTS Nous remercions tous d’abord le bon DIEU Nous exprimons notre plus grande reconnaissance envers nos chers parents qui nous ont apporté leur support moral et intellectuel tout au long de notre démarche d’étude. Nous tenons à remercier « Mme SI SALAH KARIMA » notre promotrice pour son encadrement, pour sa disponibilité qui nous a été précieuse et pour tout son suivi et ses conseils sous lesquels nous avons pu mener à bien notre travail. Nos sincères remerciements sont destinés à nos enseignants qui nous ont transmis leurs savoirs inestimables durant notre cursus universitaire ainsi que tout le staff administratif et à toute l’équipe pédagogique de la faculté SEGC. Enfin nous présentons nos vifs et chaleureux à la fois remerciements à tous les amis (es), camarades de classe, à tous ceux et celles qui de prés ou de loin ont contribué à la réussite de ce travail. Dédicaces Afin d’être reconnaissant envers ceux qui m’ont appuyé et encouragé à effectuer ce travail de recherche, je dédie ce mémoire : A ma très chère maman qui a tant œuvré pour ma réussite, de par son amour, son soutien, tous les sacrifices consentis et ses précieux conseils, pour toute son assistance et sa présence dans ma vie. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

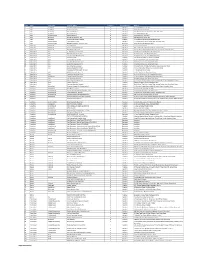

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Rapport Détaillé

Agence Française de Développement Etude stratégique sur le secteur des industries culturelles et créatives (ICC) Rapport final – Monographies et rapport des études de terrain Janvier 2018 Sommaire 1. Rapport d’études de terrain p. 2 2. Monographies p. 21 ► Liste des monographies p. 23 ► Afrique subsaharienne p. 24 ► Afrique du Nord et Moyen-Orient p. 67 ► Asie p. 86 ► Amérique latine p. 122 Page 2 Etude stratégique sur le secteur des ICC – AFD Rapport final – Monographies et rapport des études de terrain – Janvier 2018 Rapport de mission terrain Côte d’Ivoire Liste des personnes rencontrées lors du déplacement en Côte d’Ivoire ► Dates de la mission : 6 au 10 novembre 2017 Bruno Leclerc Directeur Agence AFD Côte d’Ivoire Mamidou Zoumana Coulibaly- Directeur des Infrastructures Culturelles, ► Participants : Diakité Ministère de la Culture, • Vincent Raufast, EY Advisory M. Zié Coulibaly et Directeur Directeur Institut Français et COCAC SCAC • Charles Houdart, chef de projet ICC, AFD Paris Irène Vieira Directrice du BURIDA Directrice exécutive des la conférence des • Adama Diakite, chef de projet Anna Ballo producteurs audiovisuels ICC, AFD Abidjan Maurice Kouakou Bandaman Ministre de la Culture et de la Francophonie ► La restitution de la mission de Myriam Habil Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (France) terrain en Côte d’Ivoire s’appuie Marc-Antoine Moreau CEO Universal Music Africa sur les entretiens individuels réalisés aurpès des personnes Serge Thiémélé EY Côte d’Ivoire rencontrées, dont la liste figure ci- Christian Lionel Douti Art -

Esm 102 the Nigerian Environment

ESM 102 THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT ESM 102: THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT COURSE GUIDE NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA 2 ESM 102 THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT Contents Introduction What you will learn in this course Course aims Course objectives Working through this course Course materials Study units Assessment Tutor marked Assignment (TMAs) Course overview How to get the most from this course Summary Introduction The Nigerian Environment is a one year, two credit first level course. It will be available to all students to take towards the core module of their B.Sc (Hons) in Environmental Studies/Management. It will also be appropriate as an "one-off' course for anyone who wants to be acquainted with the Nigerian Environment or/and does not intend to complete the NOU qualification. The course will be designed to content twenty units, which involves fundamental concepts and issues on the Nigerian Environment and how to control some of them. The material has been designed to assist students in Nigeria by using examples from our local communities mostly. The intention of this course therefore is to help the learner to be more familiar with the Nigerian Environment. There are no compulsory prerequisites for this course, although basic prior knowledge in geography, biology and chemistry is very important in assisting the learner through this course. This Course-Guide tells you in brief what the course is about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gave suggestions on some general guideline for the amount of time you are likely to spend on each unit of the course in order to complete it successfully. -

Case Studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria)

Open Linguistics 2021; 7: 244–300 Research Article Bruce Connell*, David Zeitlyn, Sascha Griffiths, Laura Hayward, and Marieke Martin Language ecology, language endangerment, and relict languages: Case studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria) https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2021-0011 received May 18, 2020; accepted April 09, 2021 Abstract: As a contribution to the more general discussion on causes of language endangerment and death, we describe the language ecologies of four related languages (Bà Mambila [mzk]/[mcu], Sombә (Somyev or Kila)[kgt], Oumyari Wawa [www], Njanga (Kwanja)[knp]) of the Cameroon-Nigeria borderland to reach an understanding of the factors and circumstances that have brought two of these languages, Sombә and Njanga, to the brink of extinction; a third, Oumyari, is unstable/eroded, while Bà Mambila is stable. Other related languages of the area, also endangered and in one case extinct, fit into our discussion, though with less focus. We argue that an understanding of the language ecology of a region (or of a given language) leads to an understanding of the vitality of a language. Language ecology seen as a multilayered phenom- enon can help explain why the four languages of our case studies have different degrees of vitality. This has implications for how language change is conceptualised: we see multilingualism and change (sometimes including extinction) as normative. Keywords: Mambiloid languages, linguistic evolution, language shift 1 Introduction A commonly cited cause of language endangerment across the globe is the dominance of a colonial language. The situation in Africa is often claimed to be different, with the threat being more from national or regional languages that are themselves African languages, rather than from colonial languages (Batibo 2001: 311–2, 2005; Brenzinger et al. -

S/N Bdc Name Address State 1 1 Hr Bdc

FINANCIAL POLICY AND REGULATION DEPARTMENT CONFIRMED BUREAUX DE CHANGE IN COMPLIANCE WITH NEW REQUIREMENTS S/N BDC NAME ADDRESS STATE 1 1 HR BDC LTD SUITE 24, 2ND FLOOR, KINGSWAY BUILDING, 51/52 MARINA, LAGOS LAGOS 2 19TH BDC LTD 105 ZOO ROAD, GIDAN DAN ASABE KANO 3 313 BDC LTD SUITE 5, ZONE 4 PLAZA, PLOT 2249, ADDIS ABABA CRESCENT, WUSE, ABUJA ABUJA 4 3D SCANNERS BDC LTD 2ND FLOOR, UNION ASSURANCE TOWER, 95 BROAD STREET, LAGOS LAGOS 5 6JS BDC LTD BLUECREST MALL,SUITE 51 KM43,LEKKI EPE EXPRESSWAY LAGOS 6 8-TWENTY FOUR BDC LTD PLOT 1663, BIG LEAF HOUSE, 6TH FLOOR, OYIN JOLAYEMI STREET, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS LAGOS 7 A & C BDC LTD BLOCK 9, SHOP 1/2, AGRIC MARKET, COKER, LAGOS LAGOS 16, ABAYOMI ADEWALE STREET, AGO PALACE WAY, OKOTA, ISOLO OR SUITE 122, BLOCK A2, 104 SURA SHOPPING COMPLEX, 8 A & S BDC LTD SIMPSON ST. LAGOS LAGOS 9 A A S MARMARO BDC LTD NO 43, GADANGAMI PLAZA, IBRAHIM TAIWO ROAD, KANO KANO 10 A AND B BDC LTD 12, UNITY ROAD, KANO KANO 11 A THREE BDC LTD NO. 77 OPP NNPC HOTORO, KANO KANO 12 A. W. Y. BDC LTD 10, BAYAJIDDA- LEBANON ROAD, KWARI MARKET, KANO OR 1, LEBANON ROAD, KWARI MARKET, KANO KANO 13 A.A. DANGONGOLA BDC LTD 566, TANKO SHETTIMA ROAD, WAPA, KANO KANO 14 A.A. LUKORO BDC LTD 59, YANNONO LINE, KWARI MARKET, FAGGE, TAKUDU, KANO KANO 15 A.A. SILLA BDC LTD 4, SANNI ADEWALE STREET, 2ND FLOOR, LAGOS ISLAND LAGOS 16 A.A.RANO BDC LTD NO. -

Three Years of Bloody Clashes Between Farmers

HARVEST OF DEATH THREE YEARS OF BLOODY CLASHES BETWEEN FARMERS AND HERDERS IN NIGERIA NIGERIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2018 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Cover Photos (L-R): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website:www.amnesty.org Bullet casing found in Bang, Bolki, Gon and Nzumosu Villages of Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this Adamawa State after attacks by Fulani gunmen on 2 May 2018 that material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. resulted in the dead of 33 people. © Amnesty International Nigeria First published in 2018 by Amnesty International Ltd Harvested yam burnt in Tse-Ajaver village in Taraba State when Fulani 34 Colorado Close gunmen attacked the village on 29 April 2018. off Thames Street, off Alvan Ikoku Way, © Amnesty International Nigeria Maitama, Abuja-FCT, Nigeria Njiya-Goron youths in Tabungo Village display their spears, which is the major weapons of the Bachama and Bata ethnic groups of Adamawa State. -

THE ORIGIN of the NAME NIGERIA Nigeria As Country

THE ORIGIN OF THE NAME NIGERIA Help our youth the truth to know Nigeria as country is located in West In love and Honesty to grow Africa between latitude 40 – 140 North of the And living just and true equator and longitude 30 – 140 East of the Greenwich meridian. Great lofty heights attain The name Nigeria was given by the Miss To build a nation where peace Flora Shaw in 1898 who later married Fredrick Lord Lugard who amalgamated the Northern And justice shall reign and Southern Protectorates of Nigeria in the NYSC ANTHEM year 1914 and died in 1945. Youth obey the Clarion call The official language is English and the Nation’s motto is UNITY AND FAITH, PEACE AND Let us lift our Nation high PROGRESS. Under the sun or in the rain NATIONAL ANTHEM With dedication, and selflessness Arise, O Compatriots, Nigeria’s call obey Nigeria is ours, Nigeria we serve. To serve our fatherland NIGERIA COAT OF ARMS With love and strength and faith Representation of Components The labour of our hero’s past - The Black Shield represents the good Shall never be in vain soil of Nigeria - The Eagle represents the Strength of To serve with heart and Might Nigeria One nation bound in freedom, - The Two Horses stands for dignity and pride Peace and unity. - The Y represent River Niger and River Benue. THE PLEDGE THE NIGERIAN FLAG I Pledge to Nigeria my Country The Nigeria flag has two colours To be faithful loyal and honest (Green and White) To serve Nigeria with all my strength - The Green part represents Agriculture To defend her unity - The White represents Unity and Peace.