Three Years of Bloody Clashes Between Farmers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

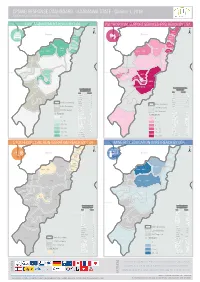

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde Madagali Maiha Mayo Belwa Michika Mubi North Mubi South Numan Toungo Shellenge Song Yola North Yola South PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Along Gombe Road, Demsa Town, Demsa Local Govt. Area Gurin Road, Adjacent Local Govt. Guest House, Fufore Local Govt. Area Along Federal Government College, Ganye Road, Ganye Lga Adjacent Local Govt. Guest Road, Girei Local Govt. Area Sangere Gombi, Aong Yola Road, Gombi L.G.A Palamale Nepa Ward Guyuk Town, Guyuk Local Govt. Area Opposite Cottage Hospital Shangui Ward, Hong Local Govt. Area Old Secretariat, Jada Along Ganye Road, Jada Lafiya Lamurde Road, Lamurde Local Govt. Area Palace Road, Gulak, Near Gulak Police Station, Madagali Lga Behind Local Govt. Secretariat, Mayonguli Ward, Maiha Jalingo Road Near Maternity Mayo Belwa Lga Michika Bye-Pass Zaibadari Ward Michika Lga Inside Local Govt. Secretariat, Mubi North Lumore Street, Opposite District Head's Palace, Gela, Mubi South Councilors Quarters, Off Jalingo Road, Numan Lga Barade Road, Oppoiste Sss Office, Toungo Old Local Govt Secretariat Street, Shelleng Town, Shelleng Lga Opp. Cattage Hospital Yola Road, Song Local Govt. Area No. 7 Demsawo Street, Demsawo Ward, Yola North Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga. -

Module 2: Investigating History

Primary Subject Resources Social Studies and the Arts Module 2 Investigating History Section 1 Investigating family histories Section 2 Investigating how we used to live Section 3 Using different forms of evidence in history Section 4 Understanding timelines Section 5 Using artefacts to explore ENGLISH TESSA (Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa) aims to improve the classroom practices of primary teachers and secondary science teachers in Africa through the provision of Open Educational Resources (OERs) to support teachers in developing student-centred, participatory approaches. The TESSA OERs provide teachers with a companion to the school textbook. They offer activities for teachers to try out in their classrooms with their students, together with case studies showing how other teachers have taught the topic, and linked resources to support teachers in developing their lesson plans and subject knowledge. TESSA OERs have been collaboratively written by African and international authors to address the curriculum and contexts. They are available for online and print use (http://www.tessafrica.net). The Primary OERs are available in several versions and languages (English, French, Arabic and Swahili). Initially, the OER were produced in English and made relevant across Africa. These OER have been versioned by TESSA partners for Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa, and translated by partners in Sudan (Arabic), Togo (French) and Tanzania (Swahili) Secondary Science OER are available in English and have been versioned for Zambia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. We welcome feedback from those who read and make use of these resources. The Creative Commons License enables users to adapt and localise the OERs further to meet local needs and contexts. -

Site Suitability for Yam, Rice and Cotton Production in Adamawa State of Nigeria: a Geographic Information System (Gis) Approach

FUTY Journal of the Environment, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2009 45 © School of Environmental Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Yola-Nigeria. ISSN 1597-8826 © School of Environmental Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Yola-Nigeria. ISSN 1597-8826 SITE SUITABILITY FOR YAM, RICE AND COTTON PRODUCTION IN ADAMAWA STATE OF NIGERIA: A GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS) APPROACH. M. Ikusemoran and T. Hajjatu Department of Geography, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Nigeria. ABSTRACT This paper demonstrated the potentials of GIS technique for mapping and delineating the suitable sites for Yam, Rice and Cotton production in Adamawa State. Site suitability mapping is necessary to create data bank and to guide the farmers in decision making on sites for crop production in the state. The use of GIS for this decision making introduces reliability and saves time with a consequent increase in agricultural productivity. The six criteria that were used for the study include soil, topography, vegetation, temperature, annual rainfall and lengths of rainy season. A combination of Ilwis 3.0 Academics, Arcview GIS 3.0 and Idrisi 32 were used for data capture and analysis. Using Boolean operations on the six criteria, and based on the requirements for each crop, all the areas that met the six conditions were considered “most suitable”. The areas with five conditions were assigned “suitable”, while the areas with four and/or three criteria were considered “just suitable”. The areas that were considered unsuitable are those areas that met no condition or the areas that met only one or two conditions. The study revealed that yam production in the state is “most suitable” in only Ganye Jada and Toungo Local Government Areas (LGA) in the Southern part of the state, covering only 5.05% of the state land mass. -

Wodaabe 1 Wodaabe

Wodaabe 1 Wodaabe Wodaabe A group of traveling Wodaabe. Niger, 1997. Total population 45,000 in 1983 Regions with significant populations Niger, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Nigeria Languages Fula Religion Islam, Oriental Orthodoxy, African traditional religion Related ethnic groups Fula The Wodaabe (Fula: Woɗaaɓe) or Bororo are a small subgroup of the Fulani ethnic group. They are traditionally nomadic cattle-herders and traders in the Sahel, with migrations stretching from southern Niger, through northern Nigeria, northeastern Cameroon, and the western region of the Central African Republic.[1] [2] The number of Wodaabe was estimated in 1983 to be 45,000.[3] They are known for their beauty (both men and women), elaborate attire and rich cultural ceremonies. The Wodaabe speak the Fula language and don't use a written language.[3] In the Fula language, woɗa means "taboo", and Woɗaaɓe means "people of the taboo". "Wodaabe" is an Anglicisation of Woɗaaɓe. [3] [4] [5] [6] This is sometimes translated as "those who respect taboos", a reference to the Wodaabe isolation from broader Fulbe culture, and their contention that they retain "older" traditions than their Fulbe neighbors.[7] In contrast, other Fulbe as well as other ethnic groups sometimes refer to the Wodaabe as "Bororo", a sometimes pejorative name,[5] translated into English as "Cattle Fulani", and meaning "those who dwell in cattle camps".[8] By the 17th century, the Fula people across West Africa were among the first ethnic groups to embrace Islam, were often leaders of those forces which spread Islam, and have been traditionally proud of the urban, literate, and pious life with which this has been related. -

Health Sector Bulletin January 2021

Northeast Nigeria Humanitarian Response COVID-19 Response OSC Medical Staff Providing Services in Mubi PHC Health Sector Bulletin January 2021 5.8 Million 5.3 Million 1.9 Million* > 4 Million*** PEOPLE IN NEED OF PEOPLE TARGETED BY IDPs IN THE THREE PEOPLE REACHED IN HEALTHCARE THE HEALTH SECTOR STATES 2020 Highlights HEALTH SECTOR Below is key highlights on COVID-19 across the BAY state as of 7th of February, 2021 45 HEALTH SECTOR PARTNERS (HRP & NON HRP) ADAMAWA STATE: • 52 new confirmed cases were reported within the week as against 47 cases reported in the preceding week. HEALTH FACILITIES IN BAY STATES** • No new death was reported within the week. • The total number of confirmed cases as of 7th February 2021 stands at 725 1529 (58.1%) FULLY FUNCTIONING with 28 deaths. 268 (10.2%) NON-FUNCTIONING • 172 samples were collected within the week as against 933 samples collected 300 (11.4%) PARTIALLY FUNCTIONING in the preceding week. 326 (12.4%) FULLY DAMAGED BORNO STATE: CUMULATIVE CONSULTATIONS • 132 new cases were confirmed for the reported week • The total number of Confirmed Cases at end of epi-week 5 stands at 1089 4.9 Million CONSULTATIONS**** • 198 active cases receiving care. 1500 REFERRALS • Total number of patients discharged for the week – 13 0.98 Million CONSULTATIONS THROUGH • Cumulative number discharged so far - 875 HARD TO REACH TEAMS • No death recorded in week 5 • Total associated deaths – 37 (25 in Isolation facilities and 12 community EARLY WARNING & ALERT RESPONSE death.) 271 EWARS SENTINEL SITES YOBE STATE: • Nine (9) new confirmed cases were reported in week 05, 2021. -

Nigeria Multi-Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA)

Nigeria Multi-Sector WASH September 2018 Needs Assessment (MSNA) ADAMAWA STATE CONTEXT AND METHODOLOGY ASSESSMENT COVERAGE Despite the increase in the number of humanitarian actors responding to the crisis in north-eastern Nigeria, humanitarian needs continue to grow as the conditions of Borno ² civilians displaced by the violent nine-year conflict remain dire. The conflict between MADAGALI armed opposition groups (AOGs) and Nigerian and regional security forces has resulted in 10.2 million affected people including remainees, internally displaced MICHIKA persons (IDPs), returnees and populations in hard-to-reach areas. These groups MUBI NORTH HONG are largely congregated in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe, the three most affected GOMBI MUBI SOUTH states in north-east Nigeria.1 Information gaps persist, which complicate the humanitarian community’s capacity for action grounded in verifiable evidence and Gombe GUYUK SHELLENG MAIHA effective coordination. SONG Amidst this context, and within the coordination framework of the United Nations LAMURDE Adamawa NUMAN GIREI Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and its Inter-Sector DEMSA YOLA SOUTH Working Group (ISWG), REACH facilitated a multi-sector needs assessment YOLA NORTH (MSNA) in all accessible areas of the most affected northeastern states of Nigeria. FUFORE Indicators and questions used in the assessment were developed with all relevant MAYO-BELWA sectors, validated and endorsed by the ISWG. This assessment, funded by the C A M E R O O N European Union Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid (ECHO), was conducted Taraba JADA from 25 June to 6 August 2018 through a total of 10,606 household (HH) surveys and 1,481 key informants interviews in 63 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of the GANYE three north-eastern states. -

Bridging Peace Between Herders and Farmers in Nigeria

BRIDGING PEACE BETWEEN HERDERS AND FARMERS IN NIGERIA. A STUDY OF BORDERLINE ON RADIO NIGERIA, ENUGU. Stella Uchenna Nwofor http://www.ajol.info/index.php/cajtms.v.12.1.2 Abstract In the past decade, Nigeria; a nation state with a population of about one hundred and sixty million people and over two hundred and fifty ethno-linguistic, socio-cultural and religious groups, had suffered pervasive violent crises with devastating impacts on the peaceful co-existence of its citizens. These crises which were either fuelled by seemingly incompatible interests and values or mere hostilities, had resulted to major outcomes such as premature deaths, gruesome casualties and general stagnation in the socio- economic growth of the communities affected and the nation at large. Several reconciliatory measures and mediation processes have been applied by the Nigerian government, as well as the international community but the results are yet not impressive. This paper presents drama as an interventionist tool for conflict resolution and social reconstruction. Using qualitative methodology, the selected radio drama attempts using a dramatic approach to expose the various perspectives to the prevalent issues of conflicts between herders and farmers in Nigeria; and calls for a peaceful co-existence amongst the ethnic groups, hence, advocating for dialogue and negotiations rather than violence and aggression as effective ways of achieving lasting peace in the nation. Keywords: Conflict, Drama, Nigeria, peace, Radio. 22 Bridging Peace Between Herders and Farmers in Nigeria. A Study of Borderline on Radio Nigeria, Enugu. Introduction Conflict is an intrinsic and inevitable part of human existence. It is as old as man and has pervaded the life cycle of most nations, communities and individuals. -

Esm 102 the Nigerian Environment

ESM 102 THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT ESM 102: THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT COURSE GUIDE NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA 2 ESM 102 THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENT Contents Introduction What you will learn in this course Course aims Course objectives Working through this course Course materials Study units Assessment Tutor marked Assignment (TMAs) Course overview How to get the most from this course Summary Introduction The Nigerian Environment is a one year, two credit first level course. It will be available to all students to take towards the core module of their B.Sc (Hons) in Environmental Studies/Management. It will also be appropriate as an "one-off' course for anyone who wants to be acquainted with the Nigerian Environment or/and does not intend to complete the NOU qualification. The course will be designed to content twenty units, which involves fundamental concepts and issues on the Nigerian Environment and how to control some of them. The material has been designed to assist students in Nigeria by using examples from our local communities mostly. The intention of this course therefore is to help the learner to be more familiar with the Nigerian Environment. There are no compulsory prerequisites for this course, although basic prior knowledge in geography, biology and chemistry is very important in assisting the learner through this course. This Course-Guide tells you in brief what the course is about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gave suggestions on some general guideline for the amount of time you are likely to spend on each unit of the course in order to complete it successfully. -

Case Studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria)

Open Linguistics 2021; 7: 244–300 Research Article Bruce Connell*, David Zeitlyn, Sascha Griffiths, Laura Hayward, and Marieke Martin Language ecology, language endangerment, and relict languages: Case studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria) https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2021-0011 received May 18, 2020; accepted April 09, 2021 Abstract: As a contribution to the more general discussion on causes of language endangerment and death, we describe the language ecologies of four related languages (Bà Mambila [mzk]/[mcu], Sombә (Somyev or Kila)[kgt], Oumyari Wawa [www], Njanga (Kwanja)[knp]) of the Cameroon-Nigeria borderland to reach an understanding of the factors and circumstances that have brought two of these languages, Sombә and Njanga, to the brink of extinction; a third, Oumyari, is unstable/eroded, while Bà Mambila is stable. Other related languages of the area, also endangered and in one case extinct, fit into our discussion, though with less focus. We argue that an understanding of the language ecology of a region (or of a given language) leads to an understanding of the vitality of a language. Language ecology seen as a multilayered phenom- enon can help explain why the four languages of our case studies have different degrees of vitality. This has implications for how language change is conceptualised: we see multilingualism and change (sometimes including extinction) as normative. Keywords: Mambiloid languages, linguistic evolution, language shift 1 Introduction A commonly cited cause of language endangerment across the globe is the dominance of a colonial language. The situation in Africa is often claimed to be different, with the threat being more from national or regional languages that are themselves African languages, rather than from colonial languages (Batibo 2001: 311–2, 2005; Brenzinger et al. -

The Roots of Mali's Conflict

The roots of Mali’s conflict The roots Mali’s of The roots of Mali’s conflict Moving beyond the 2012 crisis CRU Report Grégory Chauzal Thibault van Damme The roots of Mali’s conflict Moving beyond the 2012 crisis Grégory Chauzal Thibault van Damme CRU report March 2015 The Sahel Programme is supported by March 2015 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. About the authors Grégory Chauzal is a senior research fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit. He specialises in Mali/Sahel issues and develops the Maghreb-Sahel Programme for the Institute. Thibault Van Damme works for Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit as a project assistant for the Maghreb-Sahel Programme. About CRU The Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ is a think tank and diplomatic academy on international affairs. The Conflict Research Unit (CRU) is a specialized team within the Institute, conducting applied, policy-oriented research and developing practical tools that assist national and multilateral governmental and non-governmental organizations in their engagement in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Executive summary 8 Introduction 10 1. The 2012 crisis: the fissures of a united insurrection 10 2. A coup in the south 12 3.