A Case for the Political Redistricting of Adamawa State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of History in Northern Nigeria

The Politics of History in Northern Nigeria Niels Kastfelt Centre of African Studies University of Copenhagen Paper presented to the Research Seminar of the African Studies Centre, Leiden, 27 April 2006 The Politics of History in Contemporary Africa In recent years there has been a growing interest in the political uses of history in Africa. It is difficult to tell whether there is today a greater or more explicit political use of history than before, but it is clear that the past as a political resource does attract a strong interest from politicians and others, and that this interest takes new and highly visible forms. In this paper I shall discuss the politics of history in northern Nigeria. The discussion is based on a local case from the Nigerian Middle Belt which will be interpreted in the light of two wider contexts, that of the African continent in general and that of the specific Nigerian context. The aim of the paper is therefore double, aiming both at throwing light on the continental debate on history and on contemporary Nigerian politics. The political use of history in contemporary Africa takes many forms and so does the scholarly study of it. Without pretending to cover the entire field some main forms may be identified: “Patriotic history”: In a series of fascinating studies Terence Ranger and others have called attention to the emergence of “patriotic history” in contemporary Zimbabwe1. Zimbabwean “patriotic history” is part of the so-called “Mugabeism” launched in recent years by the regime of Robert Mugabe. The core of Mugabeism is the special version of the past called patriotic history which is promoted systematically through television, radio, newspapers and in the schools. -

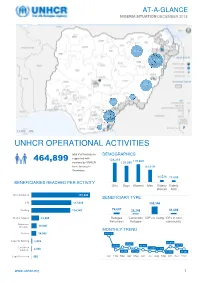

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

Iom Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State

International Organization for Migration IOM SHELTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT IN RETURN AREAS: ADAMAWA STATE October 2017 Shelter Needs Assessment Report IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State Table of Content BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 OBJECTIVE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 COVERAGE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Demographic Profile …………………………………………………………………………. 6 Housing, Land and Property ………………………………………………………………… 13 Housing Condition ……………………………………………………………………………18 Damage Assessment …………………………………………………………………………22 Access to Other Services …………………………………………………………………….29 RECOMMENDATIONS …………………………………………………………………………. 35 Page 1 IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State BACKGROUND In North-Eastern Nigeria, attacks and counter attacks have resulted in prolonged insecurity and endemic violations of human rights, triggering waves of forced displacement. Almost two million people remain displaced in Nigeria, and displacement continues to be a significant factor in 2017. Since late 2016, IOM and other humanitarian partners have been able to scale up on its activities. However, despite the will and hope of the humanitarian community and the Government of Nigeria and the dedication of teams and humanitarian partners in supporting them, humanitarian needs have drastically increased and the humanitarian response needs to keep scaling up to reach all the affected population in need. While the current humanitarian -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

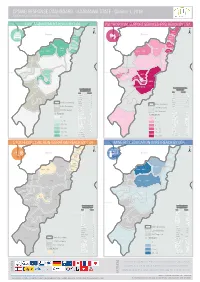

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

Comparative Economics of Fresh and Smoked Fish Marketing in Some Local Government Areas in Adamawa State, Nigeria

COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH MARKETING IN SOME LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS IN ADAMAWA STATE, NIGERIA. ONYIA, L.U., ADEBAYO, E.F., ADEWUYI, K.O., EKWUNIFE, E.G., OCHOKWU,I.J, OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION • INTRODUCTION • MATERIALS AND METHODS • RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS • CONCLUSIONS • RECOMMENDATIONS INTRODUCTION ü FISH IS A MAJOR SOURCE OF ANIMAL PROTEIN, ü ESSENTIAL FOOD ITEM IN THE DIET OF NIGERIANS (JIM-SAIKI AND OGUNBADEJO, 2003), ü AN IMPORTANT SOURCE OF LIFE AND LIVELIHOODS FOR MILLIONS OF PEOPLE AROUND THE WORLD AND FOR THAT MATTER THE SELECTED COMMUNITIES, ü PROVIDES A SPENDABLE INCOME FOR MANY FAMILIES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD (JERE AND MWENDO-PEHIRI, 2004). INTRODUCTION CONTINUED v IN NIGERIA, FISH IS SOLD TO CONSUMERS AS: ü FROZEN OR ICED, ü CURED (SMOKED), ü SUN DRIED, ü FRESH EITHER FROM A CULTURED POND OR FROM THE WILD. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY • TO IDENTIFY SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FISH MARKETERS • TO COMPARE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH ENTERPRISES IN THE STUDY AREAS. MATERIALS AND METHODS THE STUDY AREA ü SEVEN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS OF ADAMAWA STATE (NGURORE, YOLA SOUTH, YOLA NORTH, GIREI, DEMSA, FUFORE AND NUMAN) WERE RANDOMLY SELECTED BASED ON THEIR PROXIMITY TO THE FISH LANDING SITES, ü DATA COLLECTED THROUGH WELL-STRUCTURED QUESTIONNAIRE OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH MARKETERS FROM 7 MARKETS, ü 286 QUESTIONNAIRES WERE RANDOMLY DISTRIBUTED AMONG THE FISH MARKETERS. METHOD OF DATA ANALYSIS • DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS IN TERMS OF FREQUENCIES AND PERCENTAGES • GROSS MARGIN ANALYSIS WAS USED TO DETERMINE -

17 the Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production

The Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production in Mubi Region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Augustine, C1., Daniel, J.D.2, Abdulrahman, B.S.1 Lubele, M.I.3, Katsala,. J.G.4 and Ardo, M.U.4 1. Department of Animal Production, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 2. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 3. Department of History, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 4. Department of Agricultural Education, College of Education, Hong. Abstract: This study was conducted to examine the impact of Boko Haram insurgence on livestock production in Mubi region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Four local government areas (Mubi north, Mubi south, Madagali and Michika) were purposely selected for this study. Thirty (30) livestock farmers were randomly selected from each of the local government area making a total of one hundred and twenty (120) respondents. One hundred and twenty (120) structured questionnaires were administered to gather information from the farmers through an interview schedule. Majority of the livestock farmers in Mubi south (56.67%) Mubi north (63.33%), Madagali (53.33%) and Michika (80%) were males. Most of the respondents had secondary school certificates (40 to 50%) and Diploma certificates (23.33 to 36.70%). Greater proportion of the livestock farmers had family size of 5 to 10 people per family. Family labour accounted the highest (43.33 to 60%) types of labour used in managing the animals. Sizable population (53.33 to 63.33%) of the livestock farmers kept domestic animals as source of income. Livestock populations were observed to have been drastically reduced as a result of Boko Haram attacks. -

PSWG Actors Oct 2016

protectionsector COMPLETED AND W O R K I N G G R O U P NIGERIA: PROTECTION ACTORS ON-GOING ACTIVITIES N I G E R I A Agencies with registered projects in OCHA Online Project Systems (OPS) JAN - OCT 2016 COOPI (Cooperazione Internazionale) DRC (Danish Refugee Council) IOM (International Organization for Migration) POPULATION POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 3,168 REACHED 13,363 REACHED 92,911 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation YOBE BORNO Direct Implementation 3,168 10,988 66,908 JERE DIKWA MAIDUGURI 28 MAIDUGURI DAMATURU DAMATURU POTISKUM KONDUGA BAMA FIKA GWOZA BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY CHIBOK GOMBE GOMBE MICHIKA GOMBE MUBI 2 Case Referrals NORTH GIRERI GIRERI BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY 54 Capacity Building BENEFICIARIES PER ACTIVITY Unaccompanied and ADAMAWA 947 Multiple Needs ADAMAWA ADAMAWA 2 63 Livelihood Separated Children YOLA YOLA SOUTH NORTHYOLA Unaccompanied and YOLA Protection SOUTH 24 Multiple Needs 2,221 NORTH 82 Separated Children Mainstreaming FUFORE 2,375 25,975 175 Case Referrals 176 Awareness Raising / Sensitization 293 Capacity Building 271 Material Protection Assistance Psychosocial Distress Identification of 92,417 and Mental Disorder 3 6 1,727 Vulnerable Individuals 12 LOCAL GOVERNMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNIT COVERED UNIT COVERED 10,988 Dangers and Injuries UNIT COVERED NRC IRC (International Rescue Committee) NRC (Norwegian Refugee Council) Mercy Corps POPULATION POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 165,191 REACHED -

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde Madagali Maiha Mayo Belwa Michika Mubi North Mubi South Numan Toungo Shellenge Song Yola North Yola South PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Along Gombe Road, Demsa Town, Demsa Local Govt. Area Gurin Road, Adjacent Local Govt. Guest House, Fufore Local Govt. Area Along Federal Government College, Ganye Road, Ganye Lga Adjacent Local Govt. Guest Road, Girei Local Govt. Area Sangere Gombi, Aong Yola Road, Gombi L.G.A Palamale Nepa Ward Guyuk Town, Guyuk Local Govt. Area Opposite Cottage Hospital Shangui Ward, Hong Local Govt. Area Old Secretariat, Jada Along Ganye Road, Jada Lafiya Lamurde Road, Lamurde Local Govt. Area Palace Road, Gulak, Near Gulak Police Station, Madagali Lga Behind Local Govt. Secretariat, Mayonguli Ward, Maiha Jalingo Road Near Maternity Mayo Belwa Lga Michika Bye-Pass Zaibadari Ward Michika Lga Inside Local Govt. Secretariat, Mubi North Lumore Street, Opposite District Head's Palace, Gela, Mubi South Councilors Quarters, Off Jalingo Road, Numan Lga Barade Road, Oppoiste Sss Office, Toungo Old Local Govt Secretariat Street, Shelleng Town, Shelleng Lga Opp. Cattage Hospital Yola Road, Song Local Govt. Area No. 7 Demsawo Street, Demsawo Ward, Yola North Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga. -

Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020)

Nigeria: Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020) Number of Local Reporting PARTNERS PER TYPE Government Area Partners OF ORGANIZATIONS BREAKDOWN OF PEOPLE REACHED PER CATEGORY NGOs/UN People Reached PiN/Target IDP Returnee Host Agencies Community 21 Partners14 including 230,996 LGAs with ongoing International NGOs and activities 95,764 13,922 1,268 80,573 UN Agencies 11/3 212,433 DEMSA (4 Partners) MICHIKA (6 Partners) FSACI, IOM, JHF, WHO GZDI, IRC, JHF, PLAN, WHO, ZSF MADAGALI REACHED: 6,070 REACHED: 6,578 FUFORE (4 Partners) MUBI NORTH (7 Partners) MICHIKA GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, PLAN, IOM, JHF, UNICEF, WHO SWOGE, WHO REACHED: 17,309 REACHED: 6,924 MUBI NORTH GANYE (2 Partners) MUBI SOUTH (6 Partners) HONG JHF GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, RHHF, ZSF GOMBI MUBI SOUTH REACHED: - REACHED: 4,090 GIREI (4 Partners) NUMAN (1 Partner) SHELLENG JHF AGUF, IOM, JHF, WHO MAIHA REACHED: 22,348 REACHED: - SONG GUYUK GOMBI (3 Partners) SHELLENG (1 Partner) JHF GDZI, JHF, WHO LAMURDE REACHED: 220 REACHED: - GIREI GUYUK (2 Partners) SONG (2 Partners) NUMAN AGUF, JHF JHF DEMSA REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 YOLA SOUTH YOLA NORTH HONG (3 Partners) TOUNGO (1 Partner) GDZI, JHF, WHO JHF MAYO FUFORE REACHED: 423 REACHED: - BELWA JADA (1 Partner) YOLA NORTH (4 Partners) HARAF, IOM, JHF, UNICEF JHF JADA REACHED: - REACHED: 1,224 LAMURDE (1 Partner) YOLA SOUTH (4 Partners) GANYE JHF IOM, JHF, SWOGE, UNICEF Number of Organizations REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 (3 Partners) MADAGALI 1 7 JHF, PLAN, WHO TOUNGO REACHED: 4,537 MAIHA (2 Partners) JHF, WHO -

NORTHEAST NIGERIA CAMP MANAGEMENT BI-WEEKLY TRACKER REPORT Report No

NORTHEAST NIGERIA CAMP MANAGEMENT BI-WEEKLY TRACKER REPORT Report No. 23 | 01-15 October 2020. 164 189,562 823,344 154 IDP camps managed by partners Households (HH) reached by CCCM partner Individuals (ind) reached by CCCM partner Site facilitators managing in Adamawa and Borno state. agencies. agencies in Adamawa and Borno state. camps. The Camp Management bi-weekly tracker report is a service monitoring and gap analysis tool produced by the CCCM/Shelter/NFI sector. The tracker supports humanitarian partners in iden�fying gaps in assistance and service YOBE delivery. It enables stakeholders to track ac�vi�es, iden�fy gaps and thereby improving the delivery of assistance. BORNO As of September 2020, 164 camps were covered by partner agencies in the following Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Adamawa State: Fufore, Girei, Mubi South, Yola South and Yola North while in Borno State, the sites are located in Bama, Biu, Damboa, Dikwa, Gwoza, Jere, Kaga, Konduga, Mafa, Magumeri, Maiduguri, Monguno, Ngala and Nganzai LGA. KEY HIGHLIGHTS ADAMAWA The CCCM, Shelter and NFI sector in the repor�ng period of 1st -15th October received a series of Ad-hoc reports on the widespread destruc�on and damages to shelters in camps and camps-like se�ng as a result of exceeded shelters life-span and vandalism. Hence, a total of 9,656 vulnerable households in dire need of shelter, shelter repairs and essen�al non-food items (NFIs) were recorded. The affected persons are currently living in precarious LGA with CCCM activity condi�ons and are exposed to a range of protec�on threat and concerns. -

Borno State, Nearly Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa 60 000 People Face the Threat of Famine Balge Nangere Dikwa (Phase 5)

N°32 SAHEL AND MAPSMARCH & FACTS 2016 WEST AFRICA Club No 44, November 2016 ONE OUT OF THREE PEOPLE IN NORTHEASTERN NIGERIA FACED WITH ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY August-September 2016 ccording to the fi ndings of the 1 Lake A Cadre harmonisé analysis of Abadam Yusufari Chad August 2016, some 4.4 million people in Yunusari Machina Mobbar Kukawa northeastern Nigeria were facing acute Nguru Karasuwa Guzamala food insecurity (phases 3-5) requiring Bade Borsari Mobbar urgent humanitarian assistance. In Bade Geidam Nganzai Monguro the worst affected and less acces- Jakusko Marte Yobe Ngala sible pockets of Borno state, nearly Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa 60 000 people face the threat of famine Balge Nangere Dikwa (phase 5). Boko Haram attacks and Damaturu Kaga Maiduguru Potiskum Konduga Bama suicide bombings continue to cause Fika Gujba fatalities and large-scale population Borno Gwoza displacement. This has had a negative Damboa Gulani impact on food consumption and Biu Chibok Madagali livelihood activities within both Askira/Uba Kwaya Michika displaced and host community house- Kusar Hawul Hong Bayo Mubi North holds. The situation continues to Shani Girie be particularly alarming in Borno, Mubi South Shelleng Maina Adamawa and Yobe which host large Song Adamawa numbers of internally displaced Lamurde people (IDPs). According to the Inter- Numan Gombi Demsa Yola North national Organization for Migration’s Yola South (IOM) June 2016 report, there are over Fufore Mayo- 1.4 million IDPs in Borno, 159 445 in Lake Abadam Bel Yusufari Chad Jada Yunusari Machina Mobbar Kukawa Adamawa and 111 671 in Yobe. New Phases of food insecurity Nguru Karasuwa Guzamala Bade Borsari Mobbar Bade Geidam Nganzai Monguro Jakusko Marte Yobe Ngala Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa Balge Nangere Dikwa Damaturu Kaga Maiduguru Potiskum Konduga Bama Fika arrivals of IDPs put additional stress Gujba Borno Gwoza Phase 1: Minimal Gulani Damboa Ganye Biu Chibok Madagali Askira/Uba Kwaya Michika Kusar Hawul Hong Bayo Mubi North Shani Girie Mubi South Shelleng Maina on host communities.