An Evaluation of the Strahan Visitor Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rainian Uarter

e rainian uarter A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Volume LXIV, Numbers 1-2 Spring-Summer 2008 This issue is a commemorative publication on the 75th anniversary of the Stalin-induced famine in Ukraine in the years 1932-1933, known in Ukrainian as the Holodomor. The articles in this issue explore and analyze this tragedy from the perspective of several disciplines: history, historiography, sociology, psychology and literature. In memory ofthe "niwrtlered millions ana ... the graves unknown." diasporiana.org.u a The Ukrainian uarter'7 A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Since 1944 Spring-Summer 2008 Volume LXIV, No. 1-2 $25.00 BELARUS RUSSIA POLAND ROMANIA Territory of Ukraine: 850000 km2 Population: 48 millions [ Editor: Leonid Rudnytzky Deputy Editor: Sophia Martynec Associate Editor: Bernhardt G. Blumenthal Assistant Editor for Ukraine: Bohdan Oleksyuk Book Review Editor: Nicholas G. Rudnytzky Chronicle ofEvents Editor: Michael Sawkiw, Jr., UNIS Technical Editor: Marie Duplak Chief Administrative Assistant: Tamara Gallo Olexy Administrative Assistant: Liza Szonyi EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Anders Aslund Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Yaroslav Bilinsky University of Delaware, Newark, DE Viacheslav Brioukhovetsky National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Jean-Pierre Cap Professor Emeritus, Lafayette College, Easton, PA Peter Golden Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Mark von Hagen Columbia University, NY Ivan Z. Holowinsky Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Taras Hunczak Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Wsewolod Jsajiw University of Toronto, Canada Anatol F. Karas I. Franko State University of Lviv, Ukraine Stefan Kozak Warsaw University, Poland Taras Kuzio George Washington University, Washington, DC Askold Lozynskyj Ukrainian World Congress, Toronto Andrej N. Lushnycky University of Fribourg, Switzerland John S. -

Melbourne - Flinders Island - Strahan - Gordon River - King Island - Melbourne

In this new era of travel, there is no better way to explore our southern islands than by taking to the skies in a private plane. Savour a long weekend of gourmet produce, while leaving time to explore the rainforests, rivers and rich pastures of Flinders Island, north- west Tasmania and King Island. Melbourne - Flinders Island - Strahan - Gordon River - King Island - Melbourne 4 Day Interlude By Private Plane Departing 22 January 2021 $5,700 per person, twin share Single Room +$450 Day 1 - Melbourne, Flinders Island, Strahan Our private plane is bound for the Furneaux archipelago off Tasmania’s north-east coast. Alighting on Flinders Island, the largest of the group, and famous for its crayfish haul, we visit the island’s noteworthy lookouts, including Trousers Point and Vinegar Hill. After a lunch of fresh, local produce we take to the skies again for the short hop to Burnie and a scenic drive to the west-coast town of Strahan. Cocktails are served at our hilltop hotel, which overlooks the charming harbour town, after which we head out on a sunset stroll to dinner at a celebrated waterfront restaurant. Day 2 - Strahan, Gordon River Today we cruise an exquisite stretch of the Franklin-Gordon Rivers National Park aboard Spirit of the Wild. As we take in the splendour from the vessel’s Premier Upper Deck, our personal guide shares their knowledge and passion for the world-famous region while we enjoy a lunch of local delicacies, accompanied by Tasmanian wines and beers. Back in Strahan, we take our seats in the Richard Davey Amphitheatre, where history is brought to life in the highly-acclaimed play 'The Ship That Never Was'. -

Milk Composition of the New Zealand Sea Lion

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. MILK COMPOSITION OF THE NEW ZEALAND SEA LION AND FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE IT A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy . In Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Federico German Riet Sa riza 2007 ABSTRACT The objectives of the present study were to: 1) describe the gross chemical milk composition of the New Zealand sea lion (NZSLs), Phocarctos hookeri, in early lactation; 2) validate an analytical method for sea lion milk composition; 3) investigate a series of temporal, individual and dietary factors that influence the milk composition of the NZSL and; 4) investigate the temporal and spatial diffe rences in the fatty acids signatures of sea lion milk. A comprehensive literature review revealed that data on milk composition in otariid species is either missing or limited, that to be able to fully describe their milk composition extensive sampling was required and that the temporal, maternal and offspring factors that influence milk composition in pinnipeds are poorly understood . The review identified that considerable work has been conducted to infer diet via the application of fatty acids signature analysis of milk and blubber. There are many factors (Le. metabolism, de novo synthesis and endogenous sources) that contribute to the differences in fatty acid composition between the diet and milk or blubber. -

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

![[2207] Ndustria GENERAL ORDER— Pa a O Division 3— State Review Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1298/2207-ndustria-general-order-pa-a-o-division-3-state-review-of-2151298.webp)

[2207] Ndustria GENERAL ORDER— Pa a O Division 3— State Review Of

[2207] ndustria Reasons for Decision. GENERAL ORDER— THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER: This is the unani- Pa A O Division 3— mous decision of the Commission in Court Session. On 14th January this year the Commission in Court State Review of National Wage Session delivered its reasons for making a General Order restraining increases in remuneration (63 Decision, 1983— W.A.I.G. 257). The Order was made to operate for a period of six months and thereafter until further Minimum Wage Order. The Commission concluded by saying that it expected that the matter would next be the subject of proceedings before this tribunal after a review fore- BEFORE THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN shadowed by the Australian Conciliation and Arbi- INDUSTRIAL COMMISSION tration Commission in a decision which it had given No. 461 of 1983. on 23rd December, 1982 imposing a pause on improvements in pay and conditions. In the matter of the Industrial Arbitration Act, 1979 The results of that review are to be found in the and in the matter of proceedings under Division decision of the Australian Commission in the 3 of Part II of the said Act. National Wage Case 1983 (Print F2900). By virtue of Before the Commission in Court Session. section 51 of the Industrial Arbitration Act, 1979 that decision constitutes the principal subject for con- Chief Industrial Commissioner E. R. Kelly Esq; sideration in these proceedings. In addition, there is Senior Commissioner D. E. Cort and Commissioner before the Commission an application by the Trades B. J. Collier. and Labor Council (the T.L.C.) for a General Order The 13th day of October, 1983. -

Commemorative Works Catalog

DRAFT Commemorative Works by Proposed Theme for Public Comment February 18, 2010 Note: This database is part of a joint study, Washington as Commemoration, by the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service. Contact Lucy Kempf (NCPC) for more information: 202-482-7257 or [email protected]. CURRENT DATABASE This DRAFT working database includes major and many minor statues, monuments, memorials, plaques, landscapes, and gardens located on federal land in Washington, DC. Most are located on National Park Service lands and were established by separate acts of Congress. The authorization law is available upon request. The database can be mapped in GIS for spatial analysis. Many other works contribute to the capital's commemorative landscape. A Supplementary Database, found at the end of this list, includes selected works: -- Within interior courtyards of federal buildings; -- On federal land in the National Capital Region; -- Within cemeteries; -- On District of Columbia lands, private land, and land outside of embassies; -- On land belonging to universities and religious institutions -- That were authorized but never built Explanation of Database Fields: A. Lists the subject of commemoration (person, event, group, concept, etc.) and the title of the work. Alphabetized by Major Themes ("Achievement…", "America…," etc.). B. Provides address or other location information, such as building or park name. C. Descriptions of subject may include details surrounding the commemorated event or the contributions of the group or individual being commemorated. The purpose may include information about why the commemoration was established, such as a symbolic gesture or event. D. Identifies the type of land where the commemoration is located such as public, private, religious, academic; federal/local; and management agency. -

1939 June Transcript.Pdf

BLISTER BEETLES ARE here, millions of them, and if you have a caragana hedge, watch out. The blister beetle is a slim bug, about three-quarters of an inch long, dark-colored, and some times with a metallic luster. It is active, I and will take to flight quickly when disturbed. I know nothing of its origin or breeding places, or whether it is hatched locally or at a distance, but I have never noticed anything in the vicinity which I should consider the young of the species. BLISTER BEETLES IN THIS locality appear suddenly in great swarms, and their presence is usually made manifest by the bare stalks of tender caragana shoots which they have stripped of foliage. They are said to prefer reguminous plants for food. These include, among members of the pea family, the caragana and sweet pea, and among the field crops one would suppose them to be partial to alfalfa and other clovers. I don't know about this. If a swarm which has settled on a caragana hedge is disturbed by a heavy drenching of water from a garden hose the whole swarm may leave that feeding spot and settle on another hedge on the next lot. I HAVE READ THAT Because of this tendency to move when disturbed these beetles are not easily poisoned as a spray causes them to leave for more hospitable quarters. This may be true, nevertheless, the beetles can sometimes be poisoned. On Monday evening two hedges in our neighborhood and a small clump of caragana on my own lot were found heavily infested with blister beetles which had already stripped most of the leaves from the spring growth. -

Your Complete Wildlife-Watching Guide

Your complete wildlife-watching guide... 72 WHY? There’s nowhere quite like Australia; after being isolated for millenia, much of its flora and fauna is utterly unique 74 WHERE? From Queensland’s lush tropical forests and coral reefs to Tasmania’s wild and remote landscapes, and everywhere in between 88 WHAT? Australia boasts a boggling array of wildlife in its varying habitats, from the curious Platypus, to the iconic Koala 93 HOW? Suggested itineraries, facts, advice and recommendations to help you on your way Essential FLPA © AUSTRALIA ESSENTIAL AUSTRALIA Why? Australia is as varied as it is big, and much of its diverse wildlife is unique. Therefore, a visit should be savoured, not rushed. Slowly DOESWords by sTELLA MA rTINIT hanks to 35 million years of isolation, Australia’s animals wildlife. In complete contrast there are dense, dripping have evolved in their own distinctive style. From Platypuses rainforests, soaring forests of the world’s tallest flowering paddling in pristine creeks and Koalas slumped on eucalypt trees, alpine moorlands, diverse flowering heathlands, branches to Frilled Lizards skittering through savanna beaches, coastal cliffs and coral reefs. Then there is the woodlands and Thorny Devils tottering across hot desert sparsely populated savanna region, covering the northern sands, many can be seen nowhere else on Earth. While quarter of the country. Dominated by summer floods and mammals can be elusive, birds are everywhere: Rose-pink winter drought and fire, this swathe of grasslands, Galahs amass in deafening flocks at sunset; lyrebirds woodlands and wetlands includes Australia’s bio-diverse wander under tree ferns; perky fairywrens twitter in the Kakadu, Kimberley and Cape York Peninsula regions. -

Every Hour George S. Phelps A

„:\r}^} y;: k §*: • ••>•' ^;'y THE PRESS Ad- : A Home Town Paper For li^ 4pi^WW i?;:4^f-— - w .- - -..- Home Town • -;,;,;.-,-.J.r,.,i.,^. .-7.^ • ) ;....,,p. ; .. ... ^. •,,. :^J:>.fi\A. v : 7 ;•,. • Vv,: - j , v^ : :f'v >.!:-'"'-.'-:Kt' ; : ; ; ; ' '•.'\:--\i- !W' <'7 .~ ':.*U'WvWO.-Y.-V- - v-" V..'•-* ;k;:-;'rK' & Folks. THE ONLY NEWSPAPM PUBIJBHEID tN THE TOWN OF ENFIELD, CONN. mj ' • The "Press" Covers More Than Twefcty-Two Suburban Districts, GombiniiiB a Population of Over Thirty Thousand Between Hartford & Springfield ^OKTY-FiFTH YEAR—NO. 3». THOMPSONYILLB, CONNECTICUT, THURSDAY, JANUARY 22, 1925 PRICE $2.00 A YEAR—SINGLE COPY Re A^^RCE EDITORIAL St! is OTHING quite so amusing as the raids single conviction they will at least be do- : N perpetrated last Friday and Saturday ihg their duty so far as it is possible for evenings has been enacted locally for them in the suppression of lawlessness. ; Let them close down the number of "Cfoverning Board of the Board of Trade Gives Its many years. It was in truth a perfect gambling joints that are running in the Located Well Within the Shadow, the Spectacle J Endorsement To the Movement To Divide Dis- farce-comedy, with several amusing fea town under the guise of clubs, stores and Of A Lifetime, Can Be Observed By Every | trict No; 2 Into Voting Precincts and the Crea tures, which almost tempt us to assume other varied establishments. Let them the role of a dramatic critic, and point make the attempt at least to clean up Resident Here—^Totality of the Eclipse Witt 3mm.tion Of A Police Commission. -

Tasmania: the Wilderness Isle

Tasmania: The Wilderness Isle Naturetrek Tour Report 30 October - 15 November 2009 The 2009 Group in front of Cradle Mountain Cradle Mountain Wine Glass Bay in Freycinet National Park Between Strahan and Cradle Mountain Report and images compiled by Ruth Brozek Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Tasmania: The Wilderness Isle Tour Leader: Ruth Brozek Participants: David Ashby Carole Barrett Debra Dinnage Martin Dinnage Sally Davies Carole Jones Andrew Rest Day 1 Sunday 1st November Arrive Hobart, Tasmania Arrival of most of the group was delayed due to the Emirates flight late departure from Dubai. One client arrived on time from Melbourne and was met and taken to Hadleys Hotel where another client was already in residence. After introducing them and sharing a preliminary bite of lunch, I returned to Hobart Airport to meet the rest of the group, which came in on a Qantas flight from Melbourne. Lunch was therefore later than anticipated, and most welcome! There was plenty of time for the afternoon trip to Mount Wellington, and the cloud which had lain low over the mountain for most of the day showed signs of clearing. While David opted to stay and explore the city of Hobart, the rest of us set off in our minibus, the drive out passing homes of some of the more affluent colonial settlers of the 19th century, their lands now subdivided and occupied by more recent dwellings. -

Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Martin Cash/James Lester Burke

___________________________________________________________ DECONSTRUCTING AND RECONSTRUCTING THE MARTIN CASH/JAMES LESTER BURKE NARRATIVE/MANUSCRIPT OF 1870 Duane Helmer Emberg BA, BD, M Divinity, MA Communications Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2011 School of History and Classics The University of Tasmania Australia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work began in the Archives of the State Library in Hobart, Tasmania, approximately twenty-one years ago when my wife, Joan, and I discovered a large bundle of foolscap pages. They were thick with dust, neatly bound and tied with a black ribbon. I mused, ‗perhaps this is it!' Excitement mounted as we turned to Folio 1 of the faded, Victorian handwritten manuscript. Discovered was the original 1870 narrative/manuscript of bushranger Martin Cash as produced by himself and scribe/co-author, James Lester Burke. The State Archives personnel assisted in reproducing the 550 pages. They were wonderfully helpful. I wish I could remember all their names. Tony Marshall‘s help stands out. A study of the original manuscript and a careful perusal of the many editions of the Cash adventure tale alerted me that the Cash/Burke narrative/manuscript had not been fully examined before, as the twelve 1880-1981 editions of Martin Cash, His Adventures…had omitted 62,501 words which had not been published after the 1870 edition. My twenty years of study is here presented and, certainly, it would not have happened without the help of many. Geoff Stillwell (deceased) pointed me in the direction of the possible resting place of the manuscript. The most important person to help in this production was Joan. -

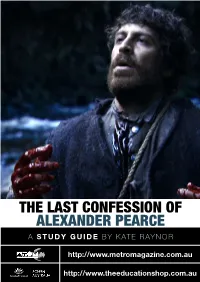

The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce a STUDY GUIDE by Kate Raynor

THE LAST CONFESSION OF ALEXANDER PEARCE A STUDY GUIDE BY KATE RAYNOR http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘It seems to me a full belly is prerequisite to all manner of good. Without that, no man will ever know what hunger can make you do.’ – Alexander Pearce Introduction the fledgling colony and a fellow Irish- important story, and would sit well man. At stake in their uneasy dialogue alongside The First Australians series n 1822, eight men escaped from the is nothing less than the soul of man. recently screened on SBS. most isolated and brutal prison on Utilizing the stunning and foreboding Iearth, Sarah Island in Van Diemen’s landscape of south-west Tasmania, The It could also work in the context of Land. Only one man survived and his Last Confession of Alexander Pearce Philosophy or Religious Studies, as it tale of betrayal, murder and cannibal- draws a visceral and compelling picture poses profound questions about the ism shocked the British establishment of the savagery and barbarism at the nature of good and evil, and redemp- to the core. The Last Confession of heart of the colony. It is an example of tion. It provides two intriguing character Alexander Pearce follows the final days Australian filmmaking at its very best. studies (Pearce and Conolly) and could of this man, Irish convict Alexander be used in English (film as text); and, Pearce, as he awaits execution. The Curriculum Links with the eloquence of its visual storytell- SCREEN EDUCATION year is 1824 and the British penal ing, it also has relevance to Film/Media colony of Van Diemen’s Land is little This film should be compulsory view- Studies.