Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Martin Cash/James Lester Burke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839. Margaret C. Dillon B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) University of Tasmania April 2008 I confirm that this thesis is entirely my own work and contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Margaret C. Dillon. -ii- This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Margaret C. Dillon -iii- Abstract This thesis examines the lives of the convict workers who constituted the primary work force in the Campbell Town district in Van Diemen’s Land during the assignment period but focuses particularly on the 1830s. Over 1000 assigned men and women, ganged government convicts, convict police and ticket holders became the district’s unfree working class. Although studies have been completed on each of the groups separately, especially female convicts and ganged convicts, no holistic studies have investigated how convicts were integrated into a district as its multi-layered working class and the ways this affected their working and leisure lives and their interactions with their employers. Research has paid particular attention to the Lower Court records for 1835 to extract both quantitative data about the management of different groups of convicts, and also to provide more specific narratives about aspects of their work and leisure. -

Parramatta's Archaeological Landscape

Parramatta’s archaeological landscape Mary Casey Settlement at Parramatta, the third British settlement in Australia after Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, began with the remaking of the landscape from an Aboriginal place, to a military redoubt and agricultural settlement, and then a township. There has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape. This analysis is important as the beginnings and changes to Parramatta are complex. The layering of the archaeology presents a confusion of possible interpretations which need a firmer historical and landscape framework through which to interpret the findings of individual archaeological sites. It involves a review of the whole range of maps, plans and images, some previously unpublished and unanalysed, within the context of the remaking of Parramatta and its archaeological landscape. The maps and images are explored through the lense of government administration and its intentions and the need to grow crops successfully to sustain the purposes of British Imperialism in the Colony of New South Wales, with its associated needs for successful agriculture, convict accommodation and the eventual development of a free settlement occupied by emancipated convicts and settlers. Parramatta’s river terraces were covered by woodlands dominated by eucalypts, in particular grey box (Eucalyptus moluccana) and forest -

Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the Historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel Et L’Historiographie De La Grande Famine

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XIX-2 | 2014 La grande famine en irlande, 1845-1851 Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel et l’historiographie de la Grande Famine Christophe Gillissen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.281 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2014 Number of pages: 195-212 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Christophe Gillissen, “Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XIX-2 | 2014, Online since 01 May 2015, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/281 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ rfcb.281 Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Charles Trevelyan, John Mitchel and the historiography of the Great Famine Christophe GILLISSEN Université de Caen – Basse Normandie The Great Irish Famine produced a staggering amount of paperwork: innumerable letters, reports, articles, tables of statistics and books were written to cover the catastrophe. Yet two distinct voices emerge from the hubbub: those of Charles Trevelyan, a British civil servant who supervised relief operations during the Famine, and John Mitchel, an Irish nationalist who blamed London for the many Famine-related deaths.1 They may be considered as representative to some extent, albeit in an extreme form, of two dominant trends within its historiography as far as London’s role during the Famine is concerned. -

The Legend of Moondyne Joe These Notes to Accompany the Legend of Moondyne Joe Provide Suggestions for Classroom Activities Base

The Legend of Moondyne Joe These notes to accompany The Legend of Moondyne Joe provide suggestions for classroom activities based on or linked to the book's text and illustrations and highlight points for discussion. Synopsis Not known for gunfights or robbing banks, it was the convict bushranger Moondyne Joe’s amazing ability to escape every time he was placed behind bars that won him fame and the affection of the early settlers. Wearing a kangaroo-skin cape and possum-skin slippers, he found freedom in the wooded valleys and winding creeks at Moondyne Hills. Joe was harmless, except possibly to a few settlers whose horses had a ‘mysterious’ way of straying. When blamed for the disappearance of a farmer’s prize stallion the colonial authorities were soon to find out that there wasn’t a jail that could hold Joe! On Writing “The Legend of Moondyne Joe” By Mark Greenwood I wanted to create a fun story, accurate in detail, about a strength of spirit that was nurtured by life in the new colony. A book that would bring to life a legend from our colourful history. I believe by having an appreciation of their own history, children better understand themselves, their community and their culture. The Legend of Moondyne Joe aims to encourage interest in our convict history to a wide audience of middle to upper primary and lower secondary age children. The picture book format allows illustrations to bring characters and settings to life. Illustrations help readers to develop a feel for bygone eras that words alone cannot portray. -

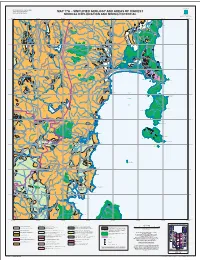

Map 17A − Simplified Geology

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP 17A − SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGY AND AREAS OF HIGHEST MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA Tasmania MINERAL EXPLORATION AND MINING POTENTIAL ENERGY and RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE SNOW River HILL Cape Lodi BADA JOS psley A MEETUS FALLS Swan Llandaff FOREST RESERVE FREYCINET Courland NATIONAL PARK Bay MOULTING LAGOON LAKE GAME RESERVE TIER Butlers Pt APSLEY LEA MARSHES KE RAMSAR SITE ROAD HWAY HIG LAKE LEAKE Cranbrook WYE LEA KE RIVER LAKE STATE RESERVE TASMAN MOULTING LAGOON MOULTING LAGOON FRIENDLY RAMSAR SITE BEACHES PRIVATE BI SANCTUARY G ROAD LOST FALLS WILDBIRD FOREST RESERVE PRIVATE SANCTUARY BLUE Friendly Pt WINGYS PARRAMORES Macquarie T IER FREYCINET NATIONAL PARK TIER DEAD DOG HILL NATURE RESERVE TIER DRY CREEK EAST R iver NATURE RESERVE Swansea Hepburn Pt Coles Bay CAPE TOURVILLE DRY CREEK WEST NATURE RESERVE Coles Bay THE QUOIN S S RD HAZA THE PRINGBAY THOUIN S Webber Pt RNMIDLAND GREAT Wineglass BAY Macq Bay u arie NORTHE Refuge Is. GLAMORGAN/ CAPE FORESTIER River To o m OYSTER PROMISE s BAY FREYCINET River PENINSULA Shelly Pt MT TOOMS BAY MT GRAHAM DI MT FREYCINET AMOND Gates Bluff S Y NORTH TOOM ERN MIDLA NDS LAKE Weatherhead Pt SOUTHERN MIDLANDS HIGHWA TI ER Mayfield TIER Bay Buxton Pt BROOKERANA FOREST RESERVE Slaughterhouse Bay CAPE DEGERANDO ROCKA RIVULET Boags Pt NATURE RESERVE SCHOUTEN PASSAGE MAN TAS BUTLERS RIDGE NATURE RESERVE Little Seaford Pt SCHOUTEN R ISLAND Swanp TIE FREYCINET ort Little Swanport NATIONAL PARK CAPE BAUDIN -

Historians, Tasmania

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 72 THE VON STIEGLITZ COLLECTION Historians, Tasmania INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.von Stieglitz Family Papers 2.Correspondence 3.Financial Records 4.Typescripts 5.Miscellaneous Records 6.Newspaper Cuttings 7.Historical Documents 8.Historical Files 9.Miscellaneous Items 10.Ephemera 11.Photographs OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION Karl Rawdon von Stieglitz was born on 19 August 1893 at Evandale, the son of John Charles and Lillian Brooke Vere (nee Stead) von Stieglitz. The first members of his family to come to Van Diemen’s Land were Frederick Lewis von Stieglitz and two of his brothers who arrived in 1829. Henry Lewis, another brother, and the father of John Charles and grandfather of Karl, arrived the following year. John Charles von Stieglitz, after qualifying as a surveyor in Tasmania, moved to Northern Queensland in 1868, where he worked as a surveyor with the Queensland Government, later acquiring properties near Townsville. In 1883, at Townsville he married Mary Mackenzie, who died in 1883. Later he went to England where he married Lillian Stead in London in 1886. On his return to Tasmania he purchased “Andora”, Evandale: the impressive house on the property was built for him in 1888. He was the MHA for Evandale from 1891 to 1903. Karl von Stieglitz visited England with his father during 1913-1914. After his father’s death in 1916, he took possession of “Andora”. He enlisted in the First World War in 1916, but after nearly a year in the AIF (AMC branch) was unable to proceed overseas due to rheumatic fever. -

250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Dr Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Vice President Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 State Secretary Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Margaret Strempel Jim Rouse Kerrie Blyth Robert Tanner Leo Prior John Gillham Libby Gillham Sandra Duck By-laws Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Assistant By-laws Officer Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editors Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 LWFHA Coordinator Anita Swan (03) 6394 8456 Members’ Interests Compiler Jim Rouse (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Coordinator Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Public Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 State Sales Officer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 29 Number 2 September 2008 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Editorial ................................................................................................................ -

Student Activity Sheet H20.3: Convict Clothing

EPISODE 20 | 1818: CHARLES Unit focus: History Year level: Years 3–6 EPISODE CLIP: FENCING ACTIVITY 1: ESCAPE! Subthemes: Culture; Gender roles and stereotypes; Historical events The remoteness of Australia and its formidable landscape and harsh climate made this alien land an ideal choice as a penal settlement in the early 19th century. While the prospect of escape may initially have seemed inconceivable, the desire for freedom proved too strong for the many convicts who attempted to flee into the bush. Early escapees were misguided by the belief that China was only a couple of hundred kilometres to the north. Later, other convicts tried to escape by sea, heading across the Pacific Ocean. In this clip, Charles meets Liam, an escaped convict who is attempting to travel over the Blue Mountains to the west. Discover Ask students to research the reasons why Australia was selected as the site of a British penal colony. They should also find out who was sent to the colony and where the convicts were first incarcerated. Refer to the My Place for Teachers, Decade timeline – 1800s for an overview. Students should write an account of the founding of the penal settlement in New South Wales. As a class, discuss the difficulties convicts faced when escaping from an early Australian gaol. Examine the reasons they escaped and the punishments inflicted when they were captured. List these reasons and punishments on the board or interactive whiteboard. For more in-depth information, students can conduct research in the school or local library, or online. -

Mary Ann Bugg – “Captain Thunderbolt's Lady.”

Mary Ann Bugg – “Captain Thunderbolt’s Lady.” Adapted with permission by Barry Sinclair, from an article written in1998 by Andrew Stackpool There were two “female bushrangers” in Australia, Mary Ann, wife, & chief lieutenant of Fred Ward and “Black Mary”, companion of Michael Howe, notorious bushranger in Tasmania in the early 1800’s. While much is made of and written about the partners of the other bushrangers, little is recorded on the life of our female bushrangers. In the case of Mary Ann, she is responsible for Fred Ward being at large for so long. Her distinct femininity and her Aboriginal heritage were probably the reason for Fred’s dislike of using firearms. She certainly taught him to read and write, and her skills developed, as part of her aboriginality, served them both well in their life in the bush. The blending of Aboriginal and European features in Mary Ann created a remarkable beauty, which was commented on many times during her career. Mary Ann Bugg was born near Gloucester/Stroud in New South Wales. Her father was a shepherd named James Brigg (who subsequently changed his name to Bugg). He was born in Essex in England in 1801 and on 18 July 1825 was transported for life for stealing meat. He arrived in Sydney on the ship “SESOSTRIS” on 26 March 1826 and on 15 January 1828 was assigned to the Australian Agricultural Company as Overseer of Shepherds. He was successful in his duties and in 1834 was granted a Ticket of Leave. This meant he was technically a free man who could own property but could not leave the Colony. -

The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 39 Issue 1 June 2012 Article 3 January 2012 The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Kühnast, Antje (2012) "The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 39 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 3 1 The Utilization of Truganini’s Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast, University of New South Wales, [email protected] Between 1904 and 1947, visitors to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart who stepped into the Aboriginal exhibition room were instantly confronted with the death of their colony’s indigenous population—or so they were led to believe. Their gaze encountered a glass case presenting the skeleton of “Truganini, The Last Tasmanian Aboriginal” (advertisement, June 24, 1905). Also known as “Queen Truganini” at her older age, representations of her reflect the many, often contradictory, interpretations of her life and agency in colonial Tasmania. She has been depicted as selfish collaborator with the colonizer, savvy savior of her race, callous resistance fighter, promiscuous prostitute who preferred whites instead of her “own” men (e.g. Rae-Ellis, 1981), and “symbol for struggle and survival” (Ryan, 1996). -

Irish Intercultural Cinema: Memory, Identity and Subjectivity

Studies in Arts and Humanities VOL01/ISSUE02/2015 ARTICLE | sahjournal.com Irish Intercultural Cinema: Memory, Identity and Subjectivity Enda Murray Sydney, Australia © Enda Murray. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Abstract Irish intercultural cinema looks at the development of a cinematic genre which focuses on issues of Irish migrancy but is produced outside of Ireland. This paper has as its focus the cultural landscape of Irish-Australia. The essay uses methodologies of ethnographic and documentary theory plus textual analysis of film and written texts to establish a throughline of Irish intercultural film. The essay begins by contextualising the place of the Irish diaspora within the creation of Irish identity globally. The discussion around migrancy is widened to consider the place of memory and intergenerational tensions within not just the Irish migrant population, but also within the diverse cultures which comprise the contemporary Australian landscape. The historical development of intercultural cinema is then explored internationally within a context of colonial, gender and class struggles in the 1970s and1980s. The term intercultural cinema has its origins in the Third Cinema of Argentinians Solanas and Getino in the 1970s and covers those films which deal with issues involving two countries or cultures. The term was refined by Laura Marks in 2000 and further developed by Hamid Naficy in 2001 in his discussion of accented cinema which narrows its definition to include the politics of production. The paper then traces the development of Irish intercultural cinema from its beginnings in England in the 1970s with Thaddeus O'Sullivan through to Nicola Bruce and others including Enda Murray in the present day. -

In the Public Interest

In the Public Interest 150 years of the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Peter Yule Copyright Victorian Auditor-General’s Office First published 2002 This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without prior written permission. ISBN 0 7311 5984 5 Front endpaper: Audit Office staff, 1907. Back endpaper: Audit Office staff, 2001. iii Foreword he year 2001 assumed much significance for the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office as Tit marked the 150th anniversary of the appointment in July 1851 of the first Victorian Auditor-General, Charles Hotson Ebden. In commemoration of this major occasion, we decided to commission a history of the 150 years of the Office and appointed Dr Peter Yule, to carry out this task. The product of the work of Peter Yule is a highly informative account of the Office over the 150 year period. Peter has skilfully analysed the personalities and key events that have characterised the functioning of the Office and indeed much of the Victorian public sector over the years. His book will be fascinating reading to anyone interested in the development of public accountability in this State and of the forces of change that have progressively impacted on the powers and responsibilities of Auditors-General. Peter Yule was ably assisted by Geoff Burrows (Associate Professor in Accounting, University of Melbourne) who, together with Graham Hamilton (former Deputy Auditor- General), provided quality external advice during the course of the project.