Rewardlessness in Orchids: How Frequent and How Rewardless? M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro Outline

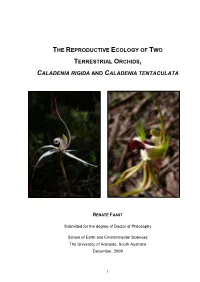

THE REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF TWO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS, CALADENIA RIGIDA AND CALADENIA TENTACULATA RENATE FAAST Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide, South Australia December, 2009 i . DEcLARATION This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution to Renate Faast and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis (as listed below) resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University's digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australasian Digital Theses Program (ADTP) and also through web search engines. Published works contained within this thesis: Faast R, Farrington L, Facelli JM, Austin AD (2009) Bees and white spiders: unravelling the pollination' syndrome of C aladenia ri gída (Orchidaceae). Australian Joumal of Botany 57:315-325. Faast R, Facelli JM (2009) Grazrngorchids: impact of florivory on two species of Calademz (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 57:361-372. Farrington L, Macgillivray P, Faast R, Austin AD (2009) Evaluating molecular tools for Calad,enia (Orchidaceae) species identification. -

Partial Endoreplication Stimulates Diversification in the Species-Richest Lineage Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.12.091074; this version posted May 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Partial endoreplication stimulates diversification in the species-richest lineage of 2 orchids 1,2,6 1,3,6 1,4,5,6 1,6 3 Zuzana Chumová , Eliška Záveská , Jan Ponert , Philipp-André Schmidt , Pavel *,1,6 4 Trávníček 5 6 1Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Botany, Zámek 1, Průhonice CZ-25243, Czech Republic 7 2Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Benátská 2, Prague CZ-12801, Czech Republic 8 3Department of Botany, University of Innsbruck, Sternwartestraße 15, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria 9 4Prague Botanical Garden, Trojská 800/196, Prague CZ-17100, Czech Republic 10 5Department of Experimental Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 5, Prague CZ- 11 12844, Czech Republic 12 13 6equal contributions 14 *corresponding author: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.12.091074; this version posted May 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 15 Abstract 16 Some of the most burning questions in biology in recent years concern differential 17 diversification along the tree of life and its causes. -

The Orchid Flora of the Colombian Department of Valle Del Cauca

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 445-462, 2014 Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 445-462, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32511 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32511445 The orchid flora of the Colombian Department of Valle del Cauca La orquideoflora del departamento colombiano de Valle del Cauca Marta Kolanowska Department of Plant Taxonomy and Nature Conservation, University of Gdańsk. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Abstract. The floristic, geographical and ecological analysis of the orchid flora of the department of Valle del Cauca are presented. The study area is located in the southwestern Colombia and it covers about 22 140 km2 of land across 4 physiographic units. All analysis are based on the fieldwork and on the revision of the herbarium material. A list of 572 orchid species occurring in the department of Valle del Cauca is presented. Two species, Arundina graminifolia and Vanilla planifolia, are non-native elements of the studied orchid flora. The greatest species diversity is observed in the montane regions of the study area, especially in wet montane forest. The department of Valle del Cauca is characterized by the high level of endemism and domination of the transitional elements within the studied flora. The main problems encountered during the research are discussed in the context of tropical floristic studies. Key words: biodiversity, ecology, distribution, Orchidaceae. Resumen. Se presentan los resultados de los estudios geográfico, ecológico y florístico de la orquideoflora del departamento colombiano del Valle del Cauca. El área de estudio está ubicada al suroccidente de Colombia y cubre aproximadamente 22 140 km2 de tierra a través de 4 unidades fisiográficas. -

Draft Survey Guidelines for Australia's Threatened Orchids

SURVEY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIA’S THREATENED ORCHIDS GUIDELINES FOR DETECTING ORCHIDS LISTED AS ‘THREATENED’ UNDER THE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ACT 1999 0 Authorship and acknowledgements A number of experts have shared their knowledge and experience for the purpose of preparing these guidelines, including Allanna Chant (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Allison Woolley (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment), Andrew Brown (Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation), Annabel Wheeler (Australian Biological Resources Study, Australian Department of the Environment), Anne Harris (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), David T. Liddle (Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, and Top End Native Plant Society), Doug Bickerton (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), John Briggs (New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage), Luke Johnston (Australian Capital Territory Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate), Sophie Petit (School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia), Melanie Smith (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Oisín Sweeney (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), Richard Schahinger (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment). Disclaimer The views and opinions contained in this document are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and while reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. -

The Orchid Flora of the Colombian Department of Valle Del Cauca Revista Mexicana De Biodiversidad, Vol

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Kolanowska, Marta The orchid flora of the Colombian Department of Valle del Cauca Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 85, núm. 2, 2014, pp. 445-462 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42531364003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 445-462, 2014 Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 445-462, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32511 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32511445 The orchid flora of the Colombian Department of Valle del Cauca La orquideoflora del departamento colombiano de Valle del Cauca Marta Kolanowska Department of Plant Taxonomy and Nature Conservation, University of Gdańsk. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Abstract. The floristic, geographical and ecological analysis of the orchid flora of the department of Valle del Cauca are presented. The study area is located in the southwestern Colombia and it covers about 22 140 km2 of land across 4 physiographic units. All analysis are based on the fieldwork and on the revision of the herbarium material. A list of 572 orchid species occurring in the department of Valle del Cauca is presented. Two species, Arundina graminifolia and Vanilla planifolia, are non-native elements of the studied orchid flora. The greatest species diversity is observed in the montane regions of the study area, especially in wet montane forest. -

Recovery Plan for Twelvve Threatened Spider-Orchid Caledenia R. Br. Taxa

RECOVERY PLAN for TWELVE THREATENED SPIDER-ORCHID CALADENIA R. Br. TAXA OF VICTORIA AND SOUTH AUSTRALIA 2000 - 2004 March 2000 Prepared by James A. Todd, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Victoria Flora and Fauna Statewide Programs Recovery Plan for twelve threatened Spider-orchid Caladenia taxa of Victoria and South Australia 2000-2004 – NRE, Victoria Copyright The Director, Environment Australia, GPO Box 636, Canberra, ACT 2601 2000. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying or other, without the prior permission of the Director, Environment Australia. Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this document are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Environment Australia, the Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Victoria, the Department of Environment and Heritage, South Australia or Parks Victoria. Citation Todd, J.A. (2000). Recovery Plan for twelve threatened Spider-orchid Caladenia taxa (Orchidaceae: Caladeniinae) of Victoria and South Australia 2000 - 2004. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne. The Environment Australia Biodiversity Group, Threatened Species and Communities Section funded the preparation of this Plan. A Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity -

Explosive Local Radiation of the Genus Teagueia (Orchidaceae) in the Upper Pastaza Watershed of Ecuador

Volume 7(1) Explosive Local Radiation of the Genus Teagueia (Orchidaceae) in the Upper Pastaza Watershed of Ecuador. Radiacion Explosivo del Genero Teagueia (Orchidaceae) en la Cuenca Alta del Rio Pastaza, Ecuador. Lou Jost Baños, Tungurahua, Ecuador, Email: [email protected] December 2004 Download at: http://www.lyonia.org/downloadPDF.php?pdfID=2.323.1 Lou Jost 42 Explosive Local Radiation of the Genus Teagueia (Orchidaceae) in the Upper Pastaza Watershed of Ecuador. Abstract In the year 2000 the genus Teagueia Luer (Orchidaceae, subtribe Pleurothallidinae) contained only six species, all epiphytic. Recently we have discovered 26 unusual new terrestrial species of Teagueia on four neighboring mountains in the Upper Pastaza Watershed. All 26 species share distinctive floral and vegetative characters not found in the six previously described members of Teagueia, suggesting that all 26 evolved locally from a recent common ancestor. Each of the Teagueia Mountains hosts 7-15 sympatric species of new Teagueia, suggesting that the speciation events, which produced this radiation, may have occurred in sympatric populations. There is little overlap in the Teagueia species hosted by the mountains, though they are separated by only 10-18 km. This is difficult to explain in light of the high dispersal ability of most orchids. Surprisingly, the species appear not to be habitat specialists. In forest above 3100 m, population densities of these new Teagueia are higher than those of any other genera of terrestrial flowering plants. In the paramos of these mountains they are the most common orchids; they reach higher elevations (3650m) than any other pleurothallid orchid except Draconanthes aberrans. -

Redalyc.EVOLUTIONARY DIVERSIFICATION AND

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Bogarín, Diego; Pupulin, Franco; Smets, Erik; Gravendeel, Barbara EVOLUTIONARY DIVERSIFICATION AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ORCHIDACEAE IN CENTRAL AMERICA WITH EMPHASIS ON COSTA RICA AND PANAMA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 16, núm. 2, 2016 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44347813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 16(2): 00–00. 2016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/lank.v16i2.00000 EVOLUTIONARY DIVERSIFICATION AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ORCHIDACEAE IN CENTRAL AMERICA WITH EMPHASIS ON COSTA RICA AND PANAMA DIEGO BOGARÍN1,2,3,7, FRANCO PUPULIN1, ERIK SMETS3,4,5 & BARBARA GRAVENDEEL3,4,6 1 Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica 2 Herbarium UCH, Autonomous University of Chiriquí, Chiriquí, Panama 3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands 4 Institute Biology Leiden, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands 5 KU Leuven, Ecology, Evolution and Biodiversity Conservation, Leuven, Belgium 6 University of Applied Sciences Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands 7 Author for correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Historically, the isthmus of Costa Rica and Panama has been a source of fascination for its strategic position linking North America to South America. In terms of biodiversity, the isthmus is considered one of the richest regions in the world. -

Dataset Attributes (Excel Spreadsheet Column Names)

Page 1 Metadata - Current Taxonomy of South Australian Vascular Plants for BDBSA (accompanies the VascularPlants_BDBSA_Taxonomy.xls spreadsheet) This document describes the excel spreadsheet VascularPlants_BDBSA_Taxonomy.xls available as a download from the Biodiversity Information Management page of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Internet Website: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/science/bio-information/how-do-i-provide.html The spreadsheet is a list of the vascular plant names that are currently deemed acceptable for entry into the Biological Databases of South Australia (BDBSA). As well as plant names accepted by the State Herbarium as current taxonomy for the Census of South Australian Vascular Plants the list also contains other allowable records for the BDBSA, for example where the full identification of a species (sp.) is not possible and only genus level can be accurately recorded (e.g. Atriplex sp.). Also, where a species has more than one subspecies (ssp.) there are records available that allow for the entry of the genus and species without having to identify to the ssp. level (e.g. Atriplex vesicaria ssp.). This list does not contain synonyms (superseded or misapplied names). To obtain a list of current plant names with their synonyms visit the Census of South Australian Plants, Algae and Fungi website [http://www.flora.sa.gov.au/census.shtml] . From the Census website you are able to print preformatted lists or produce comma separated data to load into spreadsheets etc. Data has been extracted from the FLORA database (a taxonomic reference system for Department of Environment and Natural Resources Biological Databases of SA). -

National Recovery Plan for Twenty-One Threatened Orchids in South-Eastern Australia

DRAFT for public comment National Recovery Plan for Twenty-one Threatened Orchids in South-eastern Australia Mike Duncan and Fiona Coates Prepared by Mike Duncan and Fiona Coates, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, March 2010. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74242-224-4 (online) This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Duncan, M. -

Conservation Advice Caladenia Concolor Crimson Spider Orchid

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister’s delegate approved this Conservation Advice on 16/12/2016 . Conservation Advice Caladenia concolor crimson spider orchid Conservation Status Caladenia concolor (crimson spider orchid) is listed as Vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) effective from the 16 July 2000. The species was eligible for listing under the EPBC Act as on 16 July 2000 it was listed as Vulnerable under Schedule 1 of the preceding Act, the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). Species can also be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the current listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl . The main factors that are the cause of the species being eligible for listing in the Endangered category are its restricted area or occupancy and fragmentation and continuing decline in habitat. Description The crimson spider orchid grows up to 15 – 25 cm tall is sparsely hairy, leaf is 8 – 15 cm long and 8 – 10 mm wide. The flower stem is to 25 cm tall and dark purplish red in colour bearing 1 or 2 large flowers. The flowers are also purple/red with sepals and petals 4.5 cm long, and a purple labellum with curving marginal teeth to 3 mm long. Distribution The crimson spider orchid is known to occur in Victorian Volcanic Plain, Victorian Riverina, Goldfileds, Central Victoria Uplands, Northern Inland Slopes, Southern and Nothern Highlands and Victorian alps Bioregions in Victoria and in southern New South Wales ( AVH 2014, Coates et al., 2002; NSW NPWS 2003).The species can be found on grassy or heathy open woodlands, on well drained, gravely san and clay loams (Backhouse & Jeans 1995). -

Common Epiphytes and Lithophytes of BELIZE 1 Bruce K

Common Epiphytes and Lithophytes of BELIZE 1 Bruce K. Holst, Sally Chambers, Elizabeth Gandy & Marilynn Shelley1 David Amaya, Ella Baron, Marvin Paredes, Pascual Garcia & Sayuri Tzul2 1Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 2 Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Botanical Garden © Marie Selby Bot. Gard. ([email protected]), Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Bot. Gard. ([email protected]). Photos by David Amaya (DA), Ella Baron (EB), Sally Chambers (SC), Wade Coller (WC), Pascual Garcia (PG), Elizabeth Gandy (EG), Bruce Holst (BH), Elma Kay (EK), Elizabeth Mallory (EM), Jan Meerman (JM), Marvin Paredes (MP), Dan Perales (DP), Phil Nelson (PN), David Troxell (DT) Support from the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Jungle Lodge, and many more listed in the Acknowledgments [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [1179] version 1 11/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS long the eastern slopes of the Andes and in Brazil’s Atlantic P. 1 ............. Epiphyte Overview Forest biome. In these places where conditions are favorable, epiphytes account for up to half of the total vascular plant P. 2 .............. Epiphyte Adaptive Strategies species. Worldwide, epiphytes account for nearly 10 percent P. 3 ............. Overview of major epiphytic plant families of all vascular plant species. Epiphytism (the ability to grow P. 6 .............. Lesser known epiphytic plant families as an epiphyte) has arisen many times in the plant kingdom P. 7 ............. Common epiphytic plant families and species around the world. (Pteridophytes, p. 7; Araceae, p. 9; Bromeliaceae, p. In Belize, epiphytes are represented by 34 vascular plant 11; Cactaceae, p. 15; p. Gesneriaceae, p. 17; Orchida- families which grow abundantly in many shrublands and for- ceae, p.