On the Highland Trail of Sir Arnold Bax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism Introduction Historiography

©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. Page 1 of 22 Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism A.A. den Otter ©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication or distribution is strictly prohibited. Introduction The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) has always been a symbol of Canada's nation-building experience. Poets, musicians, politicians, historians, and writers have lauded the railway as one of the country's greatest achievements. Indeed, the transcontinental railway was a remarkable accomplishment: its managers, engineers, and workers overcame incredible obstacles to throw the iron track across seemingly impenetrable bogs and forests, expansive prairies, and nearly impassable mountains. The cost in money, human energy, and lives was enormous. Completed in 1885, the CPR was one of the most important instruments by which fledgling Canada realized a vision implicit in the Confederation agreement of 1867-the building of a nation from sea to sea. In the fulfilment of this dream, the CPR, and subsequently the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk systems, allowed the easy interchange of people, ideas, and goods across a vast continent; they permitted the settlement of the Western interior and the Pacific coast; and they facilitated the integration of Atlantic Canada with the nation's heartland. In sum, by expediting commercial, political, and cultural intercourse among Canada's diverse regions, the transcontinentals in general, and the CPR in particular, strengthened the nation. Historiography The first scholarly historical analysis of the Canadian Pacific Railway was Harold Innis's A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In his daunting account of contracts, passenger traffic, freight rates, and profits, he drew some sweeping conclusions. -

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

Music Inspired by the Works of Thomas Hardy

This article was first published in The Hardy Review , Volume XVI-i, Spring 2014, pp. 29-45, and is reproduced by kind permission of The Thomas Hardy Association, editor Rosemarie Morgan. Should you wish to purchase a copy of the paper please go to: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ttha/thr/2014/00000016/0 0000001/art00004 LITERATURE INTO MUSIC: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE WORKS OF THOMAS HARDY Part Two: Music composed after Hardy’s lifetime CHARLES P. C. PETTIT Part One of this article was published in the Autumn 2013 issue. It covered music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. This second article covers music composed since Hardy’s death, coming right up to the present day. The focus is again on music by those composers who wrote operatic and orchestral works, and only mentions song settings of poems, and music in dramatisations for radio and other media, when they were written by featured composers. Hardy’s work is seen to have inspired a wide variety of music, from full-length operas and musicals, via short pieces featuring particular fictional episodes, to ballet music and purely orchestral responses. Hardy-inspired compositions show no sign of reducing in number over the decades. However despite the quantity of music produced and the quality of much of it, there is not the sense in this period that Hardy maintained the kind of universal appeal for composers that was evident during the last two decades of his life. Keywords : Thomas Hardy, Music, Opera, Far from the Madding Crowd , Tess of the d’Urbervilles , Alun Hoddinott, Benjamin Britten, Elizabeth Maconchy In my earlier article, published in the Autumn 2013 issue of the Hardy Review , I covered Hardy-inspired music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. -

ID RS Convention 2014 N Ew York

Püchner Artists performing at the IDRS Conference 2014 in New York 5–9 August 2014 New York IDRS Convention 2014 IDRS Convention Wednesday, August 6 7:30 pm Evening Gala Concert Skirball Center JONATHAN SMALL Oboe Chen Qigang, “Extase II” for Oboe and Instrumental Ensemble Thursday, August 7 8:00 pm Evening Gala Concert Skirball Center West Point Band SAXTON ROSE Bassoon Dana Wilson, “Avatar”, Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Winds Friday, August 8 1:00 pm Recital Judson Memorial Church SAXTON ROSE Bassoon Michael Gordon, “Rushes”, Rushes Ensemble 5:00 pm Gala Concert Loewe Theater ARNALDO DE FELICE Oboe “Vespri Siciliani” for Oboe and Piano FÁBIO CURY Bassoon Heitor Villa-Lobos, “Ciranda Das Sete Notas” for Bassoon and String Quintet STEFANO CANUTI Bassoon Giuseppe Tamplini, “Fantasia di Bravura su Temi di Donizetti” for Bassoon and String Quintet 8:00 pm Friday Evening Gala Concert Sunset in the Park in collaboration with the Washington Square Music Festival Washington Square Festival String Orchestra KIM WALKER Bassoon David Baker, “Trilogy” for Bassoon, Electric Bass Guitar, Strings and Percussion J.B. Dyas, Guitar (Director of the Thelonius Monk Institute) STEFANO CANUTI Bassoon Arnaldo de Felice, “Nafsha” for Bassoon and Gran Cassa, Marimba and Xylophone, American premiere Gianmaria Romanenghi, Percussion Saturday, August 9 1:00 pm Recital Judson Memorial Church FÁBIO CURY Bassoon Johann Sebastian Bach, “Sonata di Gamba g minor BWV 1029” for bassoon and harpsichord Francisco Mignone, From 16 Valses, “Sexta Valsa Brasileira”, “Mistério” and “Pattapiada” 3:00 pm Recital Shorin Recital Hall ARNALDO DE FELICE Oboe Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “Oboe quartet in F major” Benjamin Britten, “Fantasy” for Oboe and Strings www.puchner.com KIM WALKER Guest Professor at the Beijing Central Conservatory of Music Kim Walker is recognized as one of the leading international bassoon soloists, having performed on five continents and recorded more than 30 highly acclaimed CDs as a soloist and chamber musician. -

Asian Heritage Month Festival 2018 Concert Artists

Asian Heritage Month Festival 2018 Concert and Arts Showcase Artistic Directors Chan Ka Nin Chan Ka Nin is a distinguished Canadian composer whose extensive repertoire draws on both East and West in its aesthetic outlook. Professor of Theory and Composition at the University of Toronto, he has written in most musical genres and received many national and international prizes, including two JUNO awards, the Jean A. Chalmers Award, the Béla Bartók International Composers' Competition in Hungary, and the Barlow International Competition in the United States. In 2001 he won the Dora Mavor Moore Award for Outstanding Musical for his opera Iron Road, written with librettist Mark Brownell, depicting the nineteenth century construction of the Canadian National Railway by Chinese migrant labourers. Characteristically luminous in texture and exotic in instrumental colours, Prof. Chan's music has been described by critics as "sensuous," "haunting" and "intricate." The composer often draws his inspiration directly from his personal experiences: for example, the birth of one of his daughters, the death of his father, his spiritual quests, or his connection to nature and concern for the environment. Many prominent ensembles and soloists have performed his music, including the Toronto Symphony, National Arts Centre Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Calgary Philharmonic, Nova Scotia Symphony, Esprit Orchestra, Manitoba Chamber Orchestra, Amici Ensemble, Gryphon Trio, Miró Quartet, St. Lawrence Quartet, Purcell Quartet, Amherst Saxophone Quartet, violist Rivka Golani, and oboist Lawrence Cherney. His substantial discography includes releases on the CBC, Centrediscs, ATMA, Analekta, Albany, and Summit labels, among others. Born and raised in Hong Kong, Mr. Chan holds twin undergraduate degrees in electrical engineering and music from the University of British Columbia, where he studied composition with Jean Coulthard. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122714 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Music—Chinese influences. | Music—China— Western influences. | Exoticism in music. -

Proceedings of the History of Bath Research Group

PROCEEDINGS OF THE HISTORY OF BATH RESEARCH GROUP No: 5 2016-17 Trevor Fawcett 1934-2017 A noted local historian CONTENTS OBITUARY: TREVOR FAWCETT MEETING REPORTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 BATH - THE PREMIER SPA OF THE EMPIRE ................................................................................................................... 5 TRACKING NELSON THROUGH BATH 1771-1798 ........................................................................................................ 8 BATH’S DOUBTFUL SILVERSMITHS .............................................................................................................................. 12 MUSIC SHOPS AND THE MUSIC TRADE IN GEORGIAN BATH .................................................................. 14 THE LOST CHURCH OF ST. MARY DE STALLES ............................................................................................. 20 BATHWICK PUBS ................................................................................................................................................................. 23 AGM FOLLOWED BY PRESENTATIONS BY PHD STUDENTS: ............................................................................... 27 WALK: PULTENEY BRIDGE TO WIDCOMBE.................................................................................................... 33 VISIT: Bowlish house, Shepton Mallet ......................................................................................................................... -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him. -

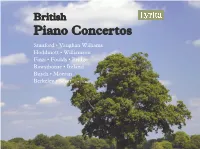

SRCD 2345 Book

British Piano Concertos Stanford • Vaughan Williams Hoddinott • Williamson Finzi • Foulds • Bridge Rawsthorne • Ireland Busch • Moeran Berkeley • Scott 1 DISC ONE 77’20” The following Scherzo falls into four parts: a fluent and ascending melody; an oppressive dance in 10/6; a return to the first section and finally the culmination of the movement where SIR CHARLES VILLIERS STANFORD (1852-1924) all the previous material collides and reaches a violent apotheosis. Of considerable metrical 1-3 intricacy, this movement derives harmonically and melodically from a four-note motif. 1st Movement: Allegro moderato 15’39” Marked , the slow movement is a set of variations which unfolds in a 2nd Movement: Adagio molto 11’32” flowing 3/2 time. Inward-looking, this is the concerto’s emotional core, its wistful opening 3rd Movement: Allegro molto 10’19” for piano establishing a mood of restrained lamentation whilst the shattering brass Malcolm Binns, piano motifs introduce a more agonized form of grief, close to raging despair. The cadenza brings London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nicholas Braithwaite some measure of peace. In the extrovert Finale, the first movement’s orchestration and metres are From SRCD219 ADD c 1985 recalled and the soloist goads the orchestra, with its ebullience restored, towards ever-greater feats of rhythmical dexterity. This typically exultant finale, in modified rondo form, re- GERALD FINZI (1901-1956) affirms the concerto’s tonal centre of E flat. 4 Though technically brilliant, it is the concerto’s unabashed lyricism