© Alan Macfarlane and Gerry Martin, 2002 1 MYOPIA: ITS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JMSCR Vol||08||Issue||02||Page 208-210||February 2020

JMSCR Vol||08||Issue||02||Page 208-210||February 2020 http://jmscr.igmpublication.org/home/ ISSN (e)-2347-176x ISSN (p) 2455-0450 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v8i2.40 Keratomalacia - A Case Report Authors Deepthi Pullepu1*, Deepthi Janga2, V Murali Krishna3 *Corresponding Author Deepthi Pullepu Department of Ophthalmology, Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract Xerophthalmia refers to an ocular condition of destructive dryness of conjunctiva and cornea caused due to severe vitamin A deficiency. Usually affects infants, children and women of reproductive age group. It is estimated to affect about one-third of children under the age of five around the world. Keratomalacia means dry and cloudy cornea which melts and perforates, caused due to severe vitamin A deficiency. Here we describe a case of 21 year old female with neurofibromatosis type 1 presenting with keratomalacia. Keywords: Vitamin A deficiency, Xerophthalmia, Keratomalacia. Introduction blindness is a significant contributor Vitamin A is essential for the functioning of the In India, it is estimated that there are immune system, healthy growth and development approximately 6.8 million people who have vision of body and is usually acquired through diet. less than 6/60 in at least one eye due to corneal Globally, 190 million children under five years of diseases; of these, about a million have bilateral age are affected by vitamin A deficiency involvement. They suffer from an increased risk of visual Corneal blindness resulting due to this disease can impairment, illness and death from childhood be completely prevented by institution of effective infections such as measles and those causing preventive or prophylactic measures at the diarrhoea community level. -

Abstract: a 19 Year Old Male Was Diagnosed with Vitamin a Deficiency

Robert Adam Young Abstract: A 19 year old male was diagnosed with vitamin A deficiency (VAD). Clinical examination shows conjunctival changes with central and marginal corneal ulcers. Patient history and lab testing were used to confirm the diagnosis. I. Case History 19 year old Hispanic Male Presents with chief complaint of progressive blur at distance and near in both eyes, foreign body sensation, ocular pain, photophobia, and epiphora; signs/symptoms are worse in the morning upon wakening. Started 6 months to 1 year ago, and has progressively gotten worse. Patient reports that the right eye is worse than the left eye. Ocular history of Ocular Rosacea Medical history of Hypoaldosteronism, Pernicious Anemia, and Type 2 Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Last eye examination was two weeks ago at a medical center Presenting topical/systemic medications - Tobramycin TID OU, Prednisolone Acetate QD OU (has used for two weeks); Fludrocortisone (used long-term per PCP) Other pertinent info includes reports that patient cannot gain weight, although he has a regular appetite. Patient presents looking very slim, malnourished, and undersized for his age. II. Pertinent findings Entering unaided acuities are 20/400 OD with no improvement with pinhole; 20/50 OS that improves to 20/25 with pinhole. Pupil testing shows (-)APD; Pupils are 6mm in dim light, and constrict to 4mm in bright light. Ocular motilities are full and smooth with no reports of diplopia or pain. Tonometry was performed with tonopen and revealed intraocular pressures of 12 mmHg OD and 11 mmHG OS. Slit lamp examination shows 2+ conjunctival injection with trace-mild bitot spots both nasal and temporal, OU. -

Current Health Issues in the Caribbean BLINDNESS in THE

Current Health Issues in the Caribbean BLINDNESS IN THE CARIBBEAN Alfred L. Anduze, M.D. St. Croix Vision Center St. Croix Hospital St. Croix U.S. Virgin Islands Caribbean Studies Association Merida, Mexico May 26, 1994 Abstract: Blindness in the Caribbean Background: The prevailing of blindness in the Caribbean region are reviewed in the context of world blindness statistics to identify differences and similarities that might exist. Method: A review of the status of blindness in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Barbados, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Mexico; individually with regard to causal etiology, epidemiology, treatment and possible future research. Results: Blindness in the Caribbean is the result of genetics, tropical environment and cultural habits of the inhabitants and consist of Age-related macular disease, Infectious diseases, Diabetes mellitus, Glaucoma, Congenital defects, Xerophthalmia, Trachoma, Trauma and Cataracts. Conclusion: There are almost 50 million people who are legally blind worldwide (i.e. with a vision of 20/200 or less) 2-3 million in the Caribbean region. The social and economic consequences are serious additional deterrents in developing countries. Outline: Causes of Blindness in the Caribbean I. Age-related macular disease a. Vascular insufficiency b. Senile macular degeneration II. Cataracts III. Glaucoma IV. Diabetes mellitus V. Infectious diseases a. Trachoma b. Onchocerciasis c. Leprosy d. Toxoplasmosis e. Toxocariasis f. AIDS VI. Trauma a. industrial/work-related b. sports c. home accidents VII. Nutritional a. Xerophthalmia/keratomalacia b. Iron-deficiency anemia c. Tobacco/Alcohol Retinopathy VIII. Congenital defects a. genetic syndromes b. strabismus Legal blindness is acceptably defined as vision 20/200 (6/60) or less. -

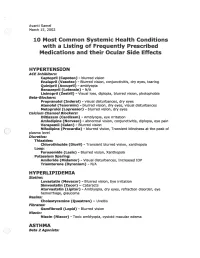

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

The Main Causes of Blindness and Low Vision in School for Blind

26ORIGINAL ARTICLE DOI 10.5935/0034-7280.20160006 The main causes of blindness and low vision in school for blind As principais causas de cegueira e baixa visão em escola para deficientes visuais Abelardo Couto Junior1, Lucas Azeredo Gonçalves de Oliveira2 ABSTRACT Objective: Identify and analyze the main causes of blindness and low vision in school for blind. Methods: One hundred sixty-five medical records of visually impaired students were reviewed in an institution specialized in teaching the blind, treated between august 2013 and may 2014. The variables analyzed were age, sex, visual acuity, primary and secondary diagnoses, treatment, optical prescription features and prognosis. Results: 165 students were evaluated, 91 students (55%) are legally blind and only 74 (45%) of the students are classified as low vision. The main causes of blindness were: retinopathy of prematurity (21%), optic nerve atrophy (18%), congenital glaucoma (16%), retinal dystrophy (11%) and cancer (8%). The causes of low vision were: congenital cataract (18%), congenital glaucoma (15%) and retinochoroidal scarring (12%). Conclusion: The main causes of blindness and low vision in the Benjamin Constant Institute are from preventable diseases. Keywords: Blindness; Low vision; Visual acuity; Child; Health school RESUMO Objetivo: Identificar e analisar as principais causas de cegueira e baixa visão em escola para deficientes visuais. Métodos: Foram revisados 165 prontuários de alunos portadores de deficiência visual em instituição especializada no ensino de cegos, atendidos no período de agosto de 2013 a maio de 2014. As variáveis analisadas foram: idade, gênero, acuidade visual, diagnóstico principal e secundário, tratamento, recursos ópticos prescritos e prognóstico. Resultados: Dos 165 alunos avaliados, 91 alunos (55%) são legalmente cegos e apenas 74 (45%) dos alunos são enquadrados como baixa visão. -

Ophthaproblem

Pratique clinique Clinical Pract ice Ophthaproblem Shaun Segal Sanjay Sharma, MD, MSC, MBA, FRCSC : Ophthalmic Photography : Ophthalmic Photography Photo credit Photo Dieu Hotel University, Laboratory of Queen’s Kingston, Ont. Hospital, 30-year-old woman had been admitted to hospital in infancy with diarrhea, steatorrhea, and failure to thrive. During late childhood, she developed atypi- Acal retinitis pigmentosa involving the retina and a progressive ataxic neuropathy. Investigations showed her serum lacked beta-lipoprotein and her red corpuscles had a spiky shape. Recent ophthalmic examination revealed substantial choroidal atrophy around the disk and a speckled peripheral fundus. Which vitamins should this patient be given as therapy for her disorder? 1. Vitamin A 2. Vitamin E 3. Vitamin C 4. Vitamin B Answer on page 1085 Mr Segal is a medical student at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. Dr Sharma is an Associate Professor of Ophthalmology and an Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at Queen’s University VOL 5: AUGUST • AOÛT 2005 d Canadian Family Physician • Le Médecin de famille canadien 1079 Pratique clinique Clinical Pract ice Answer to Ophthaproblem continued from page 1079 1. Vitamin A and 2. vitamin E Th is patient has abetalipoproteinemia (ABL), some- times called Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome,1 a dis- ease characterized by malabsorption of fat. The condition is treated with supplements of the two fat-soluble vitamins A and E. Abetalipoproteinemia manifests itself through signs of lipid malabsorp- tion, dense contracted red blood -

Prevalence and Causes of Low Vision and Blindness Worldwide

S Afr Optom 2005 64 (2) 44 − 54 Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness worldwide AO Oduntan* Department of Optometry, University of Limpopo, Private Bag X1106, Sovenga, 0727 South Africa <[email protected]> Abstract Introduction A recent review of the causes and prevalence There are many low vision and blind people of low vision and blindness world wide is lack- worldwide, and there is a considerable amount of ing. Such review is important for highlighting data available on the prevalence of low vision and the causes and prevalence of visual impairment blindness in many parts of the world. The data, in the different parts of the world. Also, it is however, vary significantly from one continent to important in providing information on the types another. In 1995, the World Health Organization and magnitude of eye care programs needed in (WHO) Task Force on data on blindness estimated different parts of the world. In this article, the that there were 37.1 million blind people world- causes and prevalence of low vision and blind- wide, indicating a global prevalence of 0.7 percent1. ness in different parts of the world are reviewed According to that report, the prevalence values and the socio-economic and psychological range from 0.3% in the developed countries to implications are briefly discussed. The review 1.4% in Sub-Saharan African countries. The preva- is based on an extensive review of the litera- lence of visual impairment is expected to be higher ture using computer data bases combined with in the developing countries due to the low level of review of available national, regional and inter- health care services in many of the countries. -

Therapy-Resistant Dry Itchy Eyes Rima Wardeh* , Volker Besgen and Walter Sekundo

Wardeh et al. Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2019) 9:13 Journal of Ophthalmic https://doi.org/10.1186/s12348-019-0178-7 Inflammation and Infection BRIEFREPORT Open Access Therapy-resistant dry itchy eyes Rima Wardeh* , Volker Besgen and Walter Sekundo Abstract An 8 years old male presented to our clinic with dry eye symptomes. Different therapiy attemps were made in the last few months and did not lead to any improvement. Examining this patient revealed multiple signs of vitamin A deficiency, which could confirmed by laboratory examination. The initial substitution of vitamin A led to a fast rehabilitation and a following nutrition consulting kept the patient symptom-free over 6 month follow up. Vitamin A deficiency -although rare in the developed countries- is an importent differential diagnosis of the dry eye especially in children. Vitamin A deficiency not only causes ocular manifistaion, but also general symptoms. Dietary change and initial subtitution is the key element for a fast and sustaining improvement. Medical history follow-up examination showed no improvement in the An 8-year-old male child was referred to our pediatric visual acuity nor in the corneal surface. In addition, the ophthalmology department because of burning sensation conjunctiva had developed triangular-shaped superficial and itching in both eyes during the last 4 months. His spots with keratinization in the bulbar conjunctiva nas- mother reported that the child was always pinching his ally, inferiorly, and temporally near the limbus of both eyes while reading or focusing. Topical therapy with eyes. With these findings, the diagnosis of conjunctival dexamethasone eye drops, antihistamine eye drops and corneal xerosis due to vitamin A deficiency was sus- (ketotifen), antibiotic eye drops (ofloxacine) and im- pected. -

The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease

DEWS Definition and Classification The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry E y e W ork Shop (2 0 0 7 ) ABSTRACT The aim of the DEWS Definition and Classifica- I. INTRODUCTION tion Subcommittee was to provide a contemporary definition he Definition and Classification Subcommittee of dry eye disease, supported within a comprehensive clas- reviewed previous definitions and classification sification framework. A new definition of dry eye was devel- T schemes for dry eye, as well as the current clinical oped to reflect current understanding of the disease, and the and basic science literature that has increased and clarified committee recommended a three-part classification system. knowledge of the factors that characteriz e and contribute to The first part is etiopathogenic and illustrates the multiple dry eye. Based on its findings, the Subcommittee presents causes of dry eye. The second is mechanistic and shows how herein an updated definition of dry eye and classifications each cause of dry eye may act through a common pathway. based on etiology, mechanisms, and severity of disease. It is stressed that any form of dry eye can interact with and exacerbate other forms of dry eye, as part of a vicious circle. II. GOALS OF THE DEFINITION AND Finally, a scheme is presented, based on the severity of the CLASSIFICATION SUBCOMMITTEE dry eye disease, which is expected to provide a rational basis The goals of the DEWS Definition and Classification for therapy. These guidelines are not intended to override the Subcommittee were to develop a contemporary definition of clinical assessment and judgment of an expert clinician in dry eye disease and to develop a three-part classification of individual cases, but they should prove helpful in the conduct dry eye, based on etiology, mechanisms, and disease stage. -

Original Article the Role and Function of Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10(7):7325-7332 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0039672 Original Article The role and function of matrix metalloproteinase-8 in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment Hong Pan1, Zhiming Zheng2 Departments of 1Ophthalmology, 2Neurosurgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250021, Shandong, People’s Republic of China Received September 7, 2016; Accepted November 18, 2016; Epub July 1, 2017; Published July 15, 2017 Abstract: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is one blinding disease, and has pathological features cor- related with migration of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells to viscous body. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) participates in eye diseases including xerophthalmia and retinal disease. Its role in RRD, however, has not been illustrated with the functional mechanism. RPE cells from RRD model mice and normal mice were separated and cultured. MMP-8 expression plasmid was transfected into RPE cell in model group. Real time PCR and Western blot were employed to test expression level of MMP-8, whilst MTT method was used to test proliferation activity of RPE cells. Caspase 3 activity was quantified by test kit. Transwell migration assay was adopted to measure invasion ability of RPE cells. ELISA method was used to test expression level of inflammatory factors interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). MMP-8 expression level was significantly decreased in RPE cells of RRD group, which also had enhanced cell proliferation and migration, accompanied with higher IL-1β and TNF-α levels (P<0.05 compared to control group). After MMP-8 transfection and over-expression, RPE cell proliferation and migration were inhibited, along with higher Caspase 3 activity, plus lower IL-1β and TNF-α expression (P<0.05 compared to model group). -

Prevention of Childhood Blindness Teaching Set

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR EYE HEALTH Prevention of Childhood Blindness Teaching Set © 1998, updated 2007, International Centre for Eye Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, WC1E 7HT, UK. Web sites: www.iceh.org.uk and www.jceh.co.uk. Supported by CBM International, HelpAge International, Sight Savers International, Task Force Sight and Life. Table of Contents 1. Childhood Blindness Worldwide 2 2. Causes of Childhood Blindness 3 3. Onset of Blindness 4 4. Examination for Eye Disease in Children 5 5. Vitamin A Deficiency and the Eye 6 6. Symptoms and Signs of Xerophthalmia 8 7. Treatment of Xerophthalmia 10 8. Prevention of Xerophthalmia 12 9. Measles and Corneal Ulceration 14 10. Prevention and Treatment of Measles 15 11. Herpes Simplex Virus 16 12. Harmful Traditional Eye Medicines 17 13. Newborn Conjunctivitis 19 14. Treatment of Newborn Conjunctivitis 21 15. Corneal Ulceration 22 16. Corneal Scarring 25 17. Congenital Cataract 26 18. Causes and Investigation of Congenital Cataract 27 19. Surgery for Congenital Cataract 29 20. Congenital Glaucoma 31 21. Retinoblastoma 33 22. Retinopathy of Prematurity 35 23. Eye Injuries 37 24. Summary 39 Acknowledgments 41 1 1. Childhood Blindness Worldwide 600,000 39% 500,000 34% 400,000 21% 300,000 200,000 Numbers of blind Numberschildren of blind 6% 100,000 0 Rich Middle Poor Very poor Standards of living and health care services How many children in the world are blind? The exact number of children blind in the world is not known but it is estimated that the figure is approximately 1.4 million, with up to 500,000 new cases every year. -

Prevention Ol Childhood Bundness

Prevention ol childhood bUndness World Health- Orpalzatloa Geaen Prevention of childhood blindness Prevention of childhood blindness World Health Organization Geneva 1992 WHO Library Catalogumg in Publication Data Prevention of childhood blindness. r.Blmdness - in infancy & childhood 2.Biindness - prevention & control ISBN 92 4 156151 3 (NLM Classification: WW 276) The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. Applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Office of Publications, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. © WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 1992 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions ofProtocol2 of the Umversal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of Its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not Imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization m preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. TYPESET IN INDIA PRINTED IN ENGLAND 91 /9088-Macmillan/Clays/GCW-s8oo Contents Preface vu Introduction I I.