Capability Brown at Blenheim Palace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Place Has Capabilities a Lancelot 'Capability' Brown Teachers Pack

This Place has Capabilities A Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown Teachers Pack Welcome to our teachers’ pack for the 2016 tercentenary of the birth of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. Lancelot Brown was born in the small village of Kirkhale in Northumberland in 1716. His name is linked with more than 250 estates, throughout England and Wales, including Stowe in Buckinghamshire, Blenheim Palace (Oxfordshire) Dinefwr Park (Carmarthenshire) and, of course Chatsworth. His first visit to Chatsworth was thought to have been in 1758 and he worked on the landscape here for over 10 years, generally visiting about twice a year to discuss plans and peg out markers so that others could get on with creating his vision. It is thought that Lancelot Brown’s nickname came from his ability to assess a site for his clients, ‘this place has its capabilities’. He was famous for taking away traditional formal gardens and avenues to create ‘natural’ landscapes and believed that if people thought his landscapes were beautiful and natural then he had succeeded. 1 Education at Chatsworth A journey of discovery chatsworth.org Index Page Chatsworth Before Brown 3 Brown’s Chatsworth 6 Work in the Park 7 Eye-catchers 8 Work in the Garden and near the House 12 Back at School 14 Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown 2 Education at Chatsworth A journey of discovery chatsworth.org Chatsworth before Brown The Chatsworth that Brown encountered looked something like this: Engraving of Chatsworth by Kip and Knyff published in Britannia Illustrata 1707 The gardens were very formal and organised, both to the front and back of the house. -

The American Lawn: Culture, Nature, Design and Sustainability

THE AMERICAN LAWN: CULTURE, NATURE, DESIGN AND SUSTAINABILITY _______________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _______________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Landscape Architecture _______________________________________________________________________________ by Maria Decker Ghys May 2013 _______________________________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Matthew Powers, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen A. Vincent, Committee Co-Chair Professor Dan Ford Professor David Pearson ABSTRACT This was an exploratory study examining the processes and underlying concepts of design nature, and culture necessary to discussing sustainable design solutions for the American lawn. A review of the literature identifies historical perceptions of the lawn and contemporary research that links lawns to sustainability. Research data was collected by conducting personal interviews with green industry professionals and administering a survey instrument to administrators and residents of planned urban development communi- ties. Recommended guidelines for the sustainable American lawn are identified and include native plant usage to increase habitat and biodiversity, permeable paving and ground cover as an alternative to lawn and hierarchical maintenance zones depending on levels of importance or use. These design recommendations form a foundation -

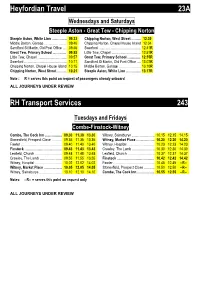

Timetables for Bus Services Under Review

Heyfordian Travel 23A Wednesdays and Saturdays Steeple Aston - Great Tew - Chipping Norton Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 09.33 Chipping Norton, West Street ……… 12.30 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 09.40 Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 12.34 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 09.46 Swerford ………………………………… 12.41R Great Tew, Primary School ………… 09.53 Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 12.51R Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 09.57 Great Tew, Primary School ………… 12.55R Swerford ………………………………… 10.11 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 13.02R Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 10.15 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 13.10R Chipping Norton, West Street ……... 10.21 Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 13.17R Note : R = serves this point on request of passengers already onboard ALL JOURNEYS UNDER REVIEW RH Transport Services 243 Tuesdays and Fridays Combe-Finstock-Witney Combe, The Cock Inn ………........ 09.30 11.30 13.30 Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.15 12.15 14.15 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 09.35 11.35 13.35 Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.20 12.20 14.20 Fawler ……………………………….. 09.40 11.40 13.40 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.23 12.23 14.23 Finstock ……………………………. 09.43 11.43 13.43 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 10.30 12.30 14.30 Leafield, Church ………………........ 09.48 11.48 13.48 Leafield, Church ………………........ 10.37 12.37 14.37 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 09.55 11.55 13.55 Finstock ……………………………. 10.42 12.42 14.42 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.02 12.02 14.02 Fawler ……………………………….. 10.45 12.45 --R-- Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.05 12.05 14.05 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 10.50 12.50 --R-- Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.10 12.10 14.10 Combe, The Cock Inn ………....... -

Designing Parterres on the Main City Squares

https://doi.org/10.24867/GRID-2020-p66 Professional paper DESIGNING PARTERRES ON THE MAIN CITY SQUARES Milena Lakićević , Ivona Simić , Radenka Kolarov University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Novi Sad, Serbia Abstract: A “parterre” is a word originating from the French, with the meaning interpreted as “on the ground”. Nowadays, this term is widely used in landscape architecture terminology and depicts a ground- level space covered by ornamental plant material. The designing parterres are generally limited to the central city zones and entrances to the valuable architectonic objects, such as government buildings, courts, museums, castles, villas, etc. There are several main types of parterres set up in France, during the period of baroque, and the most famous one is the parterre type “broderie” with the most advanced styling pattern. Nowadays, French baroque parterres are adapted and communicate with contemporary landscape design styles, but some traits and characteristics of originals are still easily recognizable. In this paper, apart from presenting a short overview of designing parterres in general, the main focus is based on designing a new parterre on the main city square in the city of Bijeljina in the Republic of Srpska. The design concept relies on principles known in the history of landscape art but is, at the same time, adjusted to local conditions and space purposes. The paper presents the current design of the selected zone – parterre on the main city square in Bijeljina and proposes a new design strongly influenced by the “broderie” type of parterre. For creating a new design proposal we have used the following software AutoCad (for 2D drawings) and Realtime Landscaping Architect (for more advanced presentations and 3D previews). -

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ a Spacious and Exceptional Quality Conversion to Create Wonderful Living Space

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ A spacious and exceptional quality conversion to create wonderful living space Oxford City Centre 6 miles, Oxford Parkway 4 miles (London, Marylebone from 56 minutes), Hanborough Station 3 miles (London, Paddington from 66 minutes), Woodstock 4.5 miles, Witney 7 miles, M40 9/12 miles. (Distances & times approximate) n Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, large study kitchen/dining room, cloakroom, utility room, boiler room, master bedroom with en suite shower room, further 3 bedrooms and family bathroom n Double garage, attractive south facing garden n In all about 0.5 acres Directions Leave Oxford on the A44 northwards, towards Woodstock. At the roundabout by The Turnpike public house, turn left signposted Yarnton. Continue through the village towards Cassington and then, on entering Worton, turn right at the sign to Jericho Farm Barns, and the entrance to Tithe Barn will be will be seen on the right after a short distance. Situation Worton is a small hamlet situated just to the east of Cassington with easy access to the A40. Within Worton is an organic farm shop and cafe that is open at weekends. Cassington has two public houses, a newsagent, garden centre, village hall and primary school. Eynsham and Woodstock offer secondary schooling, shops and other amenities. The nearby historic town of Woodstock provides a good range of shops, banks and restaurants, as well as offering the World Heritage landscaped parkland of Blenheim Palace for relaxation and walking. There are three further bedrooms, family bathroom, deep eaves storage and a box room. -

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 Steps to a Functional Design

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 steps to a functional design This worksheet will guide you through the process of Gather information designing a functional landscape plan. The process includes these steps: Step 1. Make a scale drawing • Gather information about the site and who will use it. Landscape designs are generally drawn from a bird’s- • Prioritize needs and wants. eye view in what designers call “plan view.” To prepare a base map (scale drawing) of your property use graph • Consider maintenance requirements. paper and let one square equal a certain number of feet • Determine a budget. (e.g. 1 square = 2 feet), or draw it to scale using a ruler • Organize the landscape space. or scale (e.g. 1 inch = 8 feet). • Determine the shape of the spaces and how they The base map should include these features: relate to each other. • Scale used • Select the plants that will fi ll the landscape. • North directional arrow • Property lines Base Map and Initial Site Analysis (not to scale) You may want to make several photocopies of this base map to use for the following steps in the design process. Step 2. Site analysis A thorough site analysis tells you what you have to work NICE VIEW with on the property. Part 1 of the “Home Landscape Questionnaire” (see insert) includes questions that NEED PRIVACY should be answered when completing a site analysis. Lay a piece of tracing paper over the base map and draw the information gathered during the site analysis. This layer should include these features: KITCHEN/ DINING ROOM • Basic drainage patterns -

Organic Lawn Care 101

Organic Lawn Care 101 Take Simple Steps This Fall to Convert Your Lawn to Organic Fall is the best time to start transitioning your lawn to organic. The key to a healthy lawn is healthy soil and good mowing, watering and fertilizing practices. Healthy soil contains high organic content and is teeming with biological life. Healthy soil supports the development of healthy grass that is naturally resistant to weeds and pests. In a healthy, fertile and well maintained lawn, diseases and pest problems are rare. But doesn’t it cost more you ask? If your lawn is currently chemically‐dependent, initially it may be more expensive to restore the biological life. But, in the long term, it will actually cost you less money. Once established, an organic lawn uses fewer materials, such as water and fertilizers, and requires less labor for mowing and maintenance. More importantly, your lawn will be safe for children, pets and your local drinking water supply. Getting Started‐ Late September‐ Early October 1. Mow High Until the Season Ends – Bad mowing practices cause more problems than any other cultural practice. Mowing with a dull blade makes the turf susceptible to disease and mowing too close invites sunlight in for weeds to take hold. Keep your blades sharp, or ask your service provider to sharpen their blades frequently. For the last and first mowing, mow down to 2 inches to prevent fungal problems. For the rest of the year keep it at 3‐3.5 to shade out weeds and foster deep, drought‐resistant roots. 2. Aerate – Compaction is an invitation for weeds. -

Potted Plant Availability Blooming Plants

Potted Plant Availability Blooming Plants Pot Size Product Description Pack 2.50 African Violets *1 day notice on all violets* 28 4.00 African Violets 18 4.00 African Violets Teacups or Teapots 12 6.00 African Violets 3 plants per pot 8 1204 Annual Trays See Lawn and Garden list for details 1 4.00 Annuals See Lawn and Garden list for details 18 4.00 Annuals Pk20 See Lawn and Garden list for details 20 4.25 Annuals Pk20 Proven Winners - See Lawn and Garden list 20 10.00 Annual Hanging Baskets See Lawn and Garden list for details 4 12.00 Annual Hanging Baskets See Lawn and Garden list for details 2 7.50 Annual Topiary Plants See Lawn and Garden list for details 6 10.00 Annual Topiary Plants See Lawn and Garden list for details 3 2.50 Anthurium *1 day notice on all anthurium* 18 2.50 Anthurium Self watering upgrade - RED ONLY 18 2.50 Anthurium Ceramic Upgrade 18 4.00 Anthurium 18 4.00 Anthurium In Ceramic 10 4.00 Anthurium Glass Cylinder w/ Carry Bag and Tag 10 5.00 Anthurium 10 5.00 Anthurium In Ceramic 8 6.00 Anthurium 8 6.00 Anthurium 4 inch plant in Large Vase 8 8.00 Anthurium 3 4.50 Azalea 15 6.00 Azalea Regular Temp unavailable 8 6.00 Azalea Premium 8 7.00 Azalea 6 7.00 Azalea Tree 5 8.00 Azalea 3 8.00 Azalea Tree 3 5.00 Bougainvillea Trellis 10 6.50 Bougainvillea Trellis 8 12.00 Bougainvillea Topiary 1 12.00 Bougainvillea Column 1 14.00 Bougainvillea Hanging Basket 1 6.00 Bromeliad 5 Case minimum- 1 day notice needed 8 6.00 Caladium Just Starting! Assorted mix 8 2.50 Calandiva 28 4.00 Calandiva 18 4.50 Calandiva 15 Toll Free: 1-866-866-0477 -

French & Italian Gardens

Discover glorious spring peonies French & Italian Gardens PARC MONCEAu – PARIS A pyramid is one of the many architectural set pieces and fragments that lie strewn around the Parc Monceau in Paris. They were designed to bring together the landscape and transform it into an illusory landscape by designer Louis Carmontelle who was a dramatist, illustrator and garden designer. Tombs, broken columns, an obelisk, an antique colonnade and ancient arches were all erected in 1769 for Duc de’Orleans. PARC DE BAGAtelle – PARIS The Parc de Bagatelle is a full scale picturesque landscape complete with lakes, waterfalls, Palladian or Chinese bridges and countless follies. It’s one of Paris’ best loved parks, though it’s most famous for its rose garden, created in 1905 by JCN Forestier. The very first incarnation of Bagatelle in 1777 was the result of a famous bet between Marie-Antoinette and her brother-in-law, the comte d’Artois, whom she challenged to create a garden in just two months. The Count employed 900 workmen day and night to win the wager. The architect Francois-Joseph Belanger rose to the challenge, but once the bet was won, Thomas Blaikie, a young Scotsman, was brought on board to deliver a large English-style landscape. A very successful designer, Blaikie worked in France for most of his life and collaborated on large projects such as the Parc Monceau. JARDIN DU LUXEMBOURG – PARIS Please note this garden is not included in sightseeing but can be visited in free time. The garden was made for the Italian Queen Marie (de Medici), widow of Henry IV of France and regent for her son Louis XIII. -

Lawn Or No Lawn?

Lawn or No Lawn? F ALL the things we can grow Although lawns have their The expectation that a lawn should be in our backyards, a lush, green an automatic component of a backyard is Olawn is probably the single most place in the landscape, more beginning to change. Recurring droughts popular element, so ingrained in our sense in the Southeast and West have made of what makes a backyard respectable-look- gardeners are choosing to homeowners much more selective as to ing that it transcends regionality and even where scarce water resources should be practicality. For over 75 years, a backyard forgo them in favor of more spent. Concerns for the impact on water- with a huge swath of lawn has been an in- shed health in the Northeast have also led tegral part of the iconic American subur- environmentally-friendly communities to question the wisdom of ban lifestyle. When I began my career as a using standard lawn-care chemicals. In the BY SUSAN MORRISON, PUBLISHED TIMBER PRESS, garden designer 15 years ago, it was the rare and less high-maintenance Midwest, a rediscovered appreciation of client who didn’t request the inclusion of the biodiversity that occurs in native mead- options. LESS IS MORE at least a modest-sized lawn in a backyard ows has resulted in a shift in the definition landscape design. Lately, the question of of what a lawn can be. All these examples whether a garden plan should include a point to a growing national awareness that lawn at all comes up a lot more often. -

Read the Report!

JOHN MOOREHERITAGE SERVICES AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AND RECORDING ACTION AT LAND ADJACENT TO FARWAYS, YARNTON ROAD, CASSINGTON, OXFORDSHIRE NGR SP 4553 1122 On behalf of Blenheim Palace APRIL 2015 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report REPORT FOR Blenhiem Palace Estate Office Woodstock Oxfordshire OX20 1PP PREPARED BY Andrej Čelovský, with contributions from David Gilbert, Linzi Harvey, Claire Ingrem, Frances Raymon, and Jane Timby EDITED BY David Gilbert APPROVED BY John Moore ILLUSTRATION BY Autumn Robson, Roy Entwistle, and Andrej Čelovský FIELDWORK 18th Febuery to 22nd May 2014 Paul Blockley, Andrej Čelovský, Gavin Davis, Simona Denis, Sam Pamment, and Tom Rose-Jones REPORT ISSUED 14th April 2015 ENQUIRES TO John Moore Heritage Services Hill View Woodperry Road Beckley Oxfordshire OX3 9UZ Tel/Fax 01865 358300 Email: [email protected] Site Code CAYR 13 JMHS Project No: 2938 Archive Location The archive is currently held at John Moore Heritage Services and will be deposited with Oxfordhsire County Museums Service with accession code 2013.147 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report CONTENTS Page Summary i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Site Location 1 1.2 Planning Background 1 1.3 Archaeological Background 1 2 AIMS OF THE INVESTIGATION 3 3 STRATEGY 3 3.1 Research Design 3 3.2 Methodology 3 4 RESULTS 6 4.1 Field Results 6 4.2 Bronze Age 7 4.3 Iron Age 20 4.4 Roman -

'Capability' Brown

‘Capability’ Brown & The Landscapes of Middle England Introduction (Room ) Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown was born in in the Northumbrian hamlet of Kirkharle to a family of yeoman-farmers. The local landowner, Sir William Loraine, granted him his first gardening job at Kirkharle Hall in . Demonstrating his enduring capacity for attracting aristocratic patrons, by the time he was twenty-five Viscount Cobham had promoted him to the position of Head Gardener at Stowe. Brown then secured a number of lucrative commissions in the Midlands: Newnham Paddox, Great Packington, Charlecote Park (Room ) and Warwick Castle in Warwickshire, Croome Court in Worcestershire (Room ), Weston Park in Staffordshire (Room ) and Castle Ashby in Northamptonshire. The English landscape designer Humphry Repton later commented that this rapid success was attributable to a ‘natural quickness of perception and his habitual correctness of observation’. On November Brown married Bridget Wayet. They had a daughter and three sons: Bridget, Lancelot, William and John. And in Brown set himself up as architect and landscape consultant in Hammersmith, west of London, beginning a relentlessly demanding career that would span thirty years and encompass over estates. In , coinciding directly with his newly elevated position of Royal Gardener to George , Brown embarked on several illustrious commissions, including Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, and Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire. He then took on as business partner the successful builder-architect Henry Holland the Younger. Two years later, in , Holland married Brown’s daughter Bridget, thus cementing the relationship between the two families. John Keyse Sherwin, after Nathaniel Dance, Lancelot Brown (Prof Tim Mowl) As the fashion for landscapes designed in ‘the Park way’ increased in of under-gardeners.