Skin Disease in the Bantu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immunohistochemical Analysis of S100-Positive Epidermal

An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95(5):627---630 Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia www.anaisdedermatologia.org.br DERMATOPATHOLOGY Immunohistochemical analysis of S100-positive ଝ,ଝଝ epidermal Langerhans cells in dermatofibroma Mahmoud Rezk Abdelwhaed Hussein Department of Pathology, Assuit University Hospital, Assuit, Egypt Received 3 February 2020; accepted 12 April 2020 Available online 12 July 2020 Abstract Dermatofibroma is a dermal fibrohistiocytic neoplasm. The Langerhans cells are the KEYWORDS immunocompetent cells of the epidermis, and they represent the first defense barrier of the Histiocytoma, benign immune system towards the environment. The objective was to immunohistologically compare fibrous; the densities of S100-positive Langerhans cells in the healthy peritumoral epidermis against Skin neoplasms; those in the epidermis overlying dermatofibroma (20 cases), using antibodies against the S100 S100 Proteins molecule (the immunophenotypic hallmark of Langerhans cells). The control group (normal, healthy skin) included ten healthy age and sex-matched individuals who underwent skin biopsies for benign skin lesions. A significantly high density of Langerhans cells was observed both in the epidermis of the healthy skin (6.00 ± 0.29) and the peritumoral epidermis (6.44 ± 0.41) vs. those in the epidermis overlying the tumor (1.44 ± 0.33, p < 0.05). The quantitative deficit of Langerhans cells in the epidermis overlying dermatofibroma may be a possible factor in its development. © 2020 Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia. Published by Elsevier Espana,˜ S.L.U. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Langerhans cells (LCs) are the exclusive antigen-presenting tions stained with hematoxylin and eosin as ‘‘clear cells’’ cells of the normal human epidermis. -

Storiform Collagenoma: Case Report Colagenoma Estoriforme: Relato De Caso

CASE REPORT Storiform collagenoma: case report Colagenoma estoriforme: relato de caso Guilherme Flosi Stocchero1 ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Storiform collagenoma is a rare tumor, which originates from the Storiform collagenoma or sclerotic fibroma is a rare proliferation of fibroblasts that show increased production of type-I benign skin tumor that usually affects young adults collagen. It is usually found in the face, neck and extremities, but and middle-age individuals of both sexes. This tumor is it can also appear in the trunk, scalp and, less frequently, in the slightly predominant in women. Storiform collagenoma oral mucosa and the nail bed. It affects both sexes, with a slight female predominance. It may be solitary or multiple, the latter being appears as a small papule or solid fibrous nodule. an important marker for Cowden syndrome. It presents as a painless, It is well-circumscribed, pink, whitish or skin color, solid nodular tumor that is slow-growing. It must be considered in the painless and of slow-growing. This tumor is often differential diagnosis of other well-circumscribed skin lesions, such as found in face and limbs, but it can also appears in dermatofibroma, pleomorphic fibroma, sclerotic lipoma, fibrolipoma, the chest, scalp and, rarely, in oral mucosa and nail giant cell collagenoma, benign fibrous histiocytoma, intradermal Spitz bed. Storiform collagenoma often appears as single nevus and giant cell angiohistiocytoma. tumor, and the occurrence of multiple tumors is an important indication of Cowden syndrome, which is Keywords: Collagen; Hamartoma; Skin neoplasms; Fibroma; Skin; Case a heritage genodermatosis of autosomal dominant reports condition.(1-4) Storiform collagenoma has as differential diagnosis other well-circumscribed skin tumors such RESUMO as dermatofibroma, pleomorphic fibroma, sclerotic O colagenoma estoriforme é um tumor raro originado a partir da lipoma, fibrolipoma, giant cell collagenoma, benign proliferação de fibroblastos com produção aumentada de colágeno tipo I. -

Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application Of

Letters to the Editor 301 Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application of Benzoyl Peroxide Sir, Our two patients appeared to develop an irritant response on Benzoyl peroxide (BP) is an e¡ective and frequently used topical thetrunk afterapplication of 5% benzoyl peroxide. One medication for the treatment of acne vulgaris. It is a strong, patient applied BP to his face withnoirritation,consistentwith broad spectrum bactericidal agent that signi¢cantly decreases the ¢ndings of Hausteinetal.(3). Both patients then developed the number of Propionibacterium acnes in both the follicle and apattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation after their initial der- on surface skin (1). A common side e¡ect after usage is irritation matitis subsided. Biopsy in both cases was consistent with of the skin, usually manifested as a stinging or burning, and postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation. sometimes accompanied by erythema and scaling. Benzoyl per- Postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation develops after acute oxide is a strong irritant, but a weak allergen, rarely causing a or chronic in£ammation and trauma to the skin. The intensity contact dermatitis (2, 3). Tolerance can be achieved by gradually of the hypermelanosistendstobe more pronounced in darker- increasing the frequency of application over time. We describe skinnedindividuals. Other conditions that produce a pattern of two cases in which topical application of benzoyl peroxide reticulate hyperpigmentation include Riehl's melanosis, resulted in an unusual pattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation which is characterized by reticulate brown-black pigmenta- of the skin, most likely as a sequela of an irritant contact derma- tion of the face and neck. This is thought to be a result of a titis. -

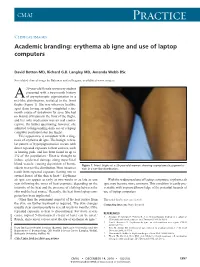

Erythema Ab Igne and Use of Laptop Computers

CMAJ Practice Clinical images Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers David Botten MD, Richard G.B. Langley MD, Amanda Webb BSc See related clinical image by Beleznay and colleagues, available at www.cmaj.ca 20-year-old female university student presented with a two-month history A of asymptomatic pigmentation in a net-like distribution, isolated to the front thighs (Figure 1). She was otherwise healthy, apart from having recently completed a six- month course of isotretinoin for acne. She had no history of trauma to the front of the thighs, and her only medication was an oral contra- ceptive. On further questioning, however, she admitted to longstanding daily use of a laptop computer positioned atop her thighs. This appearance is consistent with a diag- nosis of erythema ab igne. The benign, reticu- lar pattern of hyperpigmentation occurs with direct repeated exposure to heat sources, such as heating pads, and has been found in up to 3% of the population.1 Heat is thought to induce epidermal damage along superficial blood vessels, causing deposition of hemo- Figure 1: Front thighs of a 20-year-old woman showing asymptomatic pigmenta- siderin in a net-like distribution. Most instances tion in a net-like distribution. result from repeated exposure (lasting one to several hours) of the skin to heat.2,3 Erythema ab igne can appear as early as two weeks or as late as one With the widespread use of laptop computers, erythema ab year following the onset of heat exposure, depending on the igne may become more common. -

What Is Acne? Acne Is a Disease of the Skin's Sebaceous Glands

What is Acne? Acne is a disease of the skin’s sebaceous glands. Sebaceous glands produce oils that carry dead skin cells to the surface of the skin through follicles. When a follicle becomes clogged, the gland becomes inflamed and infected, producing a pimple. Who Gets Acne? Acne is the most common skin disease. It is most prevalent in teenagers and young adults. However, some people in their forties and fifties still get acne. What Causes Acne? There are many factors that play a role in the development of acne. Some of these include hormones, heredity, oil based cosmetics, topical steroids, and oral medications (corticosteroids, lithium, iodides, some antiepileptics). Some endocrine disorders may also predispose patients to developing acne. Skin Care Tips: Clean skin gently using a mild cleanser at least twice a day and after exercising. Scrubbing the skin can aggravate acne, making it worse. Try not to touch your skin. Squeezing or picking pimples can cause scars. Males should shave gently and infrequently if possible. Soften your beard with soap and water before putting on shaving cream. Avoid the sun. Some acne treatments will cause skin to sunburn more easily. Choose oil free makeup that is “noncomedogenic” which means that it will not clog pores. Shampoo your hair daily especially if oily. Keep hair off your face. What Makes Acne Worse? The hormone changes in females that occur 2 to 7 days prior to period starting each month. Bike helmets, backpacks, or tight collars putting pressure on acne prone skin Pollution and high humidity Squeezing or picking at pimples Scrubs containing apricot seeds. -

Review Cutaneous Patterns Are Often the Only Clue to a a R T I C L E Complex Underlying Vascular Pathology

pp11 - 46 ABstract Review Cutaneous patterns are often the only clue to a A R T I C L E complex underlying vascular pathology. Reticulate pattern is probably one of the most important DERMATOLOGICAL dermatological signs of venous or arterial pathology involving the cutaneous microvasculature and its MANIFESTATIONS OF VENOUS presence may be the only sign of an important underlying pathology. Vascular malformations such DISEASE. PART II: Reticulate as cutis marmorata congenita telangiectasia, benign forms of livedo reticularis, and sinister conditions eruptions such as Sneddon’s syndrome can all present with a reticulate eruption. The literature dealing with this KUROSH PARSI MBBS, MSc (Med), FACP, FACD subject is confusing and full of inaccuracies. Terms Departments of Dermatology, St. Vincent’s Hospital & such as livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia marmorata and retiform purpura have all been used to describe the same or entirely different conditions. To our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews of reticulate eruptions in the medical Introduction literature. he reticulate pattern is probably one of the most This article is the second in a series of papers important dermatological signs that signifies the describing the dermatological manifestations of involvement of the underlying vascular networks venous disease. Given the wide scope of phlebology T and its overlap with many other specialties, this review and the cutaneous vasculature. It is seen in benign forms was divided into multiple instalments. We dedicated of livedo reticularis and in more sinister conditions such this instalment to demystifying the reticulate as Sneddon’s syndrome. There is considerable confusion pattern. -

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans and Dermatofibroma: Dermal Dendrocytomas? a Ultrastructural Study

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans and Dermatofibroma: Dermal Dendrocytomas? A Ultrastructural Study Hugo Dominguez-Malagon, M.D., Ana Maria Cano-Valdez, M.D. Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico. ABSTRACT population of plump spindled cells devoid of cell processes, these cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid droplets and rare Dermatofibroma (DF) and Dermatofibrosarcoma subplasmalemmal densities but lacked MVB. Protuberans (DFSP) are dermal tumors whose histogenesis has not been well defined to date. The differential diagnosis in most With the ultrastructural characteristics and the constant cases is established in routine H/E sections and may be confirmed expression of CD34 in DFSP, a probable origin in dermal by immunohistochemistry; however there are atypical variants dendrocytes is postulated. The histogenesis of DF remains of DF with less clear histological differences and non-conclusive obscure. immunohistochemical results. In such cases electron microscopy studies may be useful to establish the diagnosis. INTRODUCTION In the present paper the ultrastructural characteristics of 38 The histogenesis or differentiation of cases of DFSP and 10 cases of DF are described in detail, the Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans (DFSP) and objective was to identify some features potentially useful for Dermatofibroma (DF) is controversial in the literature. For differential diagnosis, and to identify the possible histogenesis of DFSP diverse origins such as fibroblastic,1 fibro-histiocytic2 both neoplasms. Schwannian,3 myofibroblastic,4 perineurial,5,6 and endoneurial (7) have been postulated. DFSP in all cases was formed by stellate or spindled cells with long, slender, ramified cell processes joined by primitive junctions, Regarding DF, most authors are in agreement of a subplasmalemmal densities were frequently seen in the processes. -

What Is Acne and Why Do I Have Pimples?

What is acne and why do I have pimples? The medical term for “pimples” is acne. Most people develop at least some acne, especially during their teenage years. Although many believe that acne comes from being dirty, this is not true; rather, acne is the result of changes that occur during puberty. Your skin is made of layers. To keep the skin from getting dry, the skin makes oil in little wells called “sebaceous glands” that are found in the deeper layers of the skin. “Whiteheads” or “blackheads” are clogged sebaceous glands. “Blackheads” are not caused by dirt blocking the pores, but rather by oxidation (a chemical reaction that occurs when the oil reacts with oxygen in the air). People with acne have glands that make more oil and are more easily plugged, causing the glands to swell. Hormones, bacteria (called P. acnes) and your family’s likelihood to have acne (genetic susceptibility) also play a role. SKIN HYGIENE Good skin care habits are important and support the medications your doctor prescribes for your acne. » Wash your face twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening (which includes any showers you take). » Avoid over-washing/over-scrubbing your face as this will not improve the acne and may lead to dryness and irritation, which can interfere with your medications. » In general, milder soaps and cleansers are better for acne-prone skin. The soaps labeled “for sensitive skin” are milder than those labeled “deodorant soap” or “antibacterial soap.” » Many “acne washes” may contain salicylic acid. Salicylic acid (SA) fights oil and bacteria mildly but can be drying and can add to irritation. -

JMSCR Vol||06||Issue||03||Page 652-655||March 2018

JMSCR Vol||06||Issue||03||Page 652-655||March 2018 www.jmscr.igmpublication.org Impact Factor (SJIF): 6.379 Index Copernicus Value: 71.58 ISSN (e)-2347-176x ISSN (p) 2455-0450 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v6i3.110 A Clinico-Pathological Correlation Study of the Spectrum of Non-Infectious, Scaly Skin Lesions Authors Dr Priya Banthavi Sivasubramanian1, Dr R.Suganya2, Dr Manimegalai Singaram3, Dr V.Sarada4, Dr N. Balasubramanian5 1Associate Professor of Pathology, Chennai Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Irungalur, Tiruchirappalli 621105 2Assistant Professor of Pathology, Chennai Medical College Hospital And Research Centre, Irungalur, Tiruchirappalli.621105 3Consultant Pathologist, Tiruchirappalli.621105 4Prof and Head, Dept of Pathology, Chennai Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Irungalur, Tiruchirappalli.621105 5Prof and Head, Dept of Dermatology, Chennai Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Irungalur, Tiruchirappalli.621105 Corresponding Author Dr Priya Banthavi Sivasubramanian Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Chennai Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Irungalur, Tiruchirappalli, Tamilnadu.621105 Email: [email protected], Phone: 9842445404 Abstract A prospective correlation study was done on 51 patients, clinically diagnosed to have non-infectious, scaly skin lesions falling under the spectrum of Papulosquamous disorders. Thirty six of these patients were found to have good clinical and histopathological correlation. Keywords: non-infectious scaly skin lesions, papulosquamous disease. Introduction dermatologist in instituting proper therapy and can Papulosquamous diseases form the largest vary the prognosis significantly. conglomerate group of skin disease(1) wherein all are characterized by scaling papules, hence Materials and Methods confusion may result in their clinical diagnosis. All patients attending the Dermatology OPD Therefore, histopathological analysis is important between July 2014 and June 2016, with a clinical for a more definitive differentiation. -

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

Sunburn, Suntan and the Risk of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma the Western Canada Melanoma Study J.M

Br. J. Cancer (1985), 51, 543-549 Sunburn, suntan and the risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma The Western Canada Melanoma Study J.M. Elwood1, R.P. Gallagher2, J. Davison' & G.B. Hill3 1Department of Community Health, University of Nottingham, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, UK; 2Division of Epidemiology and Biometry, Cancer Control Agency of British Columbia, 2656 Heather Street, Vancouver BC, Canada V5Z 3J3; and 3Department of Epidemiology, Alberta Cancer Board, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G OTT2. Summary A comparison of interview data on 595 patients with newly incident cutaneous melanoma, excluding lentigo maligna melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma, with data from comparison subjects drawn from the general population, showed that melanoma risk increased in association with the frequency and severity of past episodes of sunburn, and also that melanoma risk was higher in subjects who usually had a relatively mild degree of suntan compared to those with moderate or deep suntan in both winter and summer. The associations with sunburn and with suntan were independent. Melanoma risk is also increased in association with a tendency to burn easily and tan poorly and with pigmentation characteristics of light hair and skin colour, and history freckles; the associations with sunburn and suntan are no longer significant when these other factors are taken into account. This shows that pigmentation characteristics, and the usual skin reaction to sun, are more closely associated with melanoma risk than are sunburn and suntan histories. -

Basal Cell Carcinoma Associated with Non-Neoplastic Cutaneous Conditions: a Comprehensive Review

Volume 27 Number 2| February 2021 Dermatology Online Journal || Review 27(2):1 Basal cell carcinoma associated with non-neoplastic cutaneous conditions: a comprehensive review Philip R Cohen MD1,2 Affiliations: 1San Diego Family Dermatology, National City, California, USA, 2Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, California, USA Corresponding Author: Philip R Cohen, 10991 Twinleaf Court, San Diego, CA 92131-3643, Email: [email protected] pathogenesis of BCC is associated with the Abstract hedgehog signaling pathway and mutations in the Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can be a component of a patched homologue 1 (PCTH-1) transmembrane collision tumor in which the skin cancer is present at tumor-suppressing protein [2-4]. Several potential the same cutaneous site as either a benign tumor or risk factors influence the development of BCC a malignant neoplasm. However, BCC can also concurrently occur at the same skin location as a non- including exposure to ultraviolet radiation, genetic neoplastic cutaneous condition. These include predisposition, genodermatoses, immunosuppression, autoimmune diseases (vitiligo), cutaneous disorders and trauma [5]. (Darier disease), dermal conditions (granuloma Basal cell carcinoma usually presents as an isolated faciale), dermal depositions (amyloid, calcinosis cutis, cutaneous focal mucinosis, osteoma cutis, and tumor on sun-exposed skin [6-9]. However, they can tattoo), dermatitis, miscellaneous conditions occur as collision tumors—referred to as BCC- (rhinophyma, sarcoidal reaction, and varicose veins), associated multiple skin neoplasms at one site scars, surgical sites, systemic diseases (sarcoidosis), (MUSK IN A NEST)—in which either a benign and/or systemic infections (leischmaniasis, leprosy and malignant neoplasm is associated with the BCC at lupus vulgaris), and ulcers.