The Function of Illustration in the Books Written by Maurice Sendak and Mercer Mayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Guide 5Th - 8Th Grades

Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are, © 1963 by Maurice Sendak, all rights reserved. Curriculum Guide 5th - 8th Grades In a Nutshell:the Worlds of Maurice Sendak is on display jan 4 - feb 24, 2012 l main library l 301 york street In a Nutshell: The Worlds of Maurice Sendak was organized by the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia, and developed by Nextbook, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting Jewish literature, culture, and ideas, and the American Library Association Public Programs Office. The national tour of the exhibit has been made possible by grants from the Charles H. Revson Foundation, the Righteous Persons Foundation, the David Berg Foundation, and an anonymous donor, with additional support from Tablet Magazine: A New Read on Jewish Life. About the Exhibit About Maurice Sendak will be held at the Main Library, 301 York St., downtown, January 4th to February 24th, 2012. Popular children’s author Maurice Sendak’s typically American childhood in New York City inspired many of his most beloved books, such as Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. Illustrations in those works are populated with friends, family, and the sights, sounds and smells of New York in the 1930s. But Sendak was also drawn to photos of ancestors, and he developed a fascination with the shtetl world of European Jews. This exhibit, curated by Patrick Rodgers of the Rosenbach Museum & Library Maurice Sendak comes from Brooklyn, New York. in Philadelphia, reveals the push and pull of New and Old He was born in 1928, the youngest of three children. -

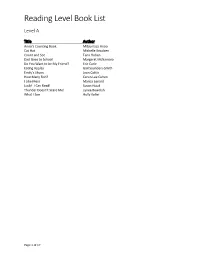

Book List by Reading Level

Reading Level Book List Level A Title Author Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anoo Cat Hat Michelle Knudsen Count and See Tana Hoban Dad Goes to School Margaret McNamara Do You Want to be My Friend? Eric Carle Eating Apples Gail Saunders-Smith Emily’s Shoes Joan Cottle How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen I Like Mess Marcia Lenard Look! I Can Read! Susan Hood Thunder Doesn’t Scare Me! Lynea Bowdish What I See Holly Keller Page 1 of 17 Reading Level Book List Level B Title Author Bravo, Kazam! Amy Ehrlich Eddie the Raccoon Catherine Friend Ethan at Home Johanna Hurwitz Get the Ball, Slim Marcia Leonard Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle How Many Fish? Caron Cohen I Love My Family Joy Cowley Larry and the Cookie Becky McDaniel The Long, Long Tail Joy Cowley Mommy, Where are you? Leonid Gore Major Jump Joy Cowley Mouse has Fun Phyllis Root My Puppy Joy Cowley Piggy and Dad Go Fishing David Martin Snap! Joy Cowley Page 2 of 17 Reading Level Book List Level C Title Author Along Comes Jake Joy Cowley The Best Place Susan Meddaugh Big and Little Joy Cowley Brown Bear, Brown Bear Bill Martin, Jr. Bugs! Pat McKissack Bunny, Bunny Kirsten Hall A Hug is Warm Joy Cowley I Went Walking Sue Williams Ice Cream Joy Cowley I’m Bigger Than You! Joy Cowley Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie Let’s Have a Swim Joy Cowley Little Brother Joy Cowley One Hunter Pat Hutchins Our Granny Joy Cowley Our Street Joy Cowley Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie DePaola The Race Joy Cowley Rainbow of My Own Don Freeman Spots, Feathers and -

Typography, Illustration and Narration in Three Novels by Alasdair Gray

Title Page. Typography, Illustration and Narration in Three Novels by Alasdair Gray: Lanark, 1982, Janine and Poor Things. Craig Linwood Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Humanities Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2017 Abstract. The impetus of the thesis emerged through an academic interest in how experimental uses of typography and illustration functioned as a method of narration within literature. This was followed by investigations into the use of typography and illustration yielded that while there is a growing field of literary study examining non-linguistic elements within narratives, there are few studies into typography and illustration and how an author utilises and develops them as a method of narration. In light of this, this thesis examines attempts to expand upon the act of narration through the use of typography and illustration in both experimental and common forms. This is focused through Scottish artist Alasdair Gray and three of his novels: Lanark: A Life in Four Books, 1982, Janine and Poor Things. While Gray’s novels are contemporary his use of typography and illustration engages in wider print cultures that facilitated experiment into literature involving the manipulation of typography, illustration and the traditions of narrative. Experimentation in literature from 1650 to 1990, be it through illustration, typography or the composition of narrative, often emerged when printing practice and its product were no longer seen as efficient at communicating to modernising audiences. This act often coincided with larger changes within print cultures that affected laws, politics, the means of distribution, views of design i and methods of distribution. -

A Brief History of Children's Storybooks

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AN ORIGINAL STORY WITH RELIEF PRINT ILLUSTRATIONS MARILYN TURNER MCPHERON Fall 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Art with honors in Art Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robin Gibson Associate Professor of Art Thesis Supervisor Jerrold Maddox Professor of Art Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College ABSTRACT Children’s literature, in the form of picture and storybooks, introduce a child to one of the most important tools needed to succeed in life: the ability to read. With the availability of affordable books in the 18th century, due to the introduction of new mechanization, individuals had the ability to improve their lives and widen their worlds. In the 19th century, writers of fiction began to specialize in literature for children. In the 20th century, books for children, with beautiful, colorful illustrations, became a common gift for children. The relatively rapid progression from moralistic small pamphlets on cheap paper with crude woodcuts to the world of Berenstain Bears, colorful Golden Books, and the tongue-twisters of Dr. Seuss is an intriguing social change. The story of how a storybook moves from an idea to the bookstore shelf is equally fascinating. Combining the history of children’s literature with how a storybook is created inspired me to write and illustrate my own children’s book, ―OH NO, MORE SNOW!‖ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Schreyer Honors College, -

The Illustrated Book Cover Illustrations

THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: A collection of 18 pronouncements by Buddhist sages accompanied by their pictures. n.p., n.d. Manuscript scroll folded into 42 pages, written on leaves of the bodhi tree. Chinese text, beginning with the date wu-shu of Tao kuang [·i.e. 1838 ] Wooden covers. Picture of Buddhist sage Hsu tung on front cover, accompanied by text of his pronouncement on separate leaf on back cover: "A Buddhist priest asked Buddha, 'How did the Buddha attain the most superior way?' Buddha replied, 'Protect the heart from sins; as one shines a mirror by keeping off dust, one can attain enlightenment.'" --i~ ti_ Hsu tung THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK • An Exhibit: March-May 1991 • Compiled by Alice N. Loranth Cleveland Public Library Fine Arts and Special Collections Department PREFACE The Illustrated Book exhibit was assembled to present an overview of the history of book illustration for a general audience. The plan and scope of the exhibit were developed within the confines of available exhibit space on the third floor of Main Library. Materials were selected from the holdings of Special Collections, supplemented by a few titles chosen from the collections of Fine Arts. Selection of materials was further restrained by concern for the physical well-being of very brittle or valuable items. Many rare items were omitted from the exhibit in order to safeguard them from the detrimental effects of an extended exhibit period. Book illustration is a cooperation of word and picture. At the beginning, writing itself was pictorial, as words were expressed through pictorial representation. -

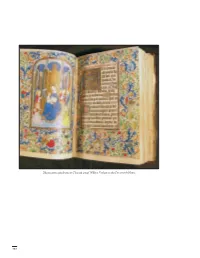

Illumination Attributed to Flemish Artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours

Illumination attributed to Flemish artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours. 132 Book Arts a Medieval Manuscripts Georgetown’s largest collection of late medieval and early renaissance documents, the Scheuch Collection, is described in the European History chapter. In addition to that collection, the library possesses nearly a score of early liturgical and theological manuscripts, including some with interesting and sometimes significant miniatures and illumina tion. Those held prior to 1970 are for the most part listed in Seymour de Ricci’s Census or its supplement, but special note should be made of the volume of spiritual opuscules in Old French (gift of John Gooch) and the altus part of the second set of the musical anthology known as the “Scots Psalter” (1586) by Thomas Wode (or Wood) of St. Andrews, possibly from the library of John Gilmary Shea. Also of note are two quite remarkable fifteenth-century manuscripts: one with texts of Bede, Hugh of St. Victor, and others (gift of Ralph A. Hamilton); the other containing works by Henry of Hesse, St. John Chrysostom, and others (gift of John H. Drury). In recent years the collection has Euclid, Elementa geometriae (1482). grown with two important additions: a truly first-rate manuscript, the Farnsworth Hours, probably illuminated in Bruges about 1465 by Willem Vrelant (gift of Mrs. Thomas M. Evans), and a previously unrecorded fifteenth-century Flemish manuscript of the Imitatio Christi in a very nearly contemporary binding (gift of the estate of Louise A. Emling). The relatively small number of complete manuscripts is supplemented, especially for teaching purposes, by a variety of leaves from individual manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the sixteenth century (in part the gifts of Bishop Michael Portier, Frederick Schneider, Mrs. -

Educator Resource Guide

Educator Resource Guide By Maurice Sendak Originally adapted for the stage by Carol Healas and TAG Theatre, Glasgow Produced by Presentation House Theatre Curriculum Subject Areas English Language Arts | Arts Education Health & Career Education | Social Studies 1 We are thrilled that you have decided to bring your students to Carousel Theatre for Welcome! Young People! This Resource Guide was adapted by Peter Church from the original by Bev Haskins, and we hope that you find it useful in the classroom. The games and exercises contained inside have been arranged according to recommended grade levels, but please feel free to add and adjust the activities to suit your needs. If you have any questions or suggestions, please give us a call at 604.669.3410 or email us at [email protected]. PS. If any of your students would like to tell us what they thought of the show, please mail us letters and pictures, we love to receive mail! For our contact information please visit the last page of this guide. Contents Synopsis 3 Other Books Written & Illustrated by Maurice Sendak 3 About Presentation House Theatre 3 A Note from Kim Selody, Director 4 Keep an eye out for these yellow Class Reading List 5 boxes on each of the Classroom Classroom Activities – Before the Play 6 Activities! Classroom Activities - After the Play 8 Our Curriculum Ties can assist with the Prescribed Learning Creative Team 18 Outcomes in B.C.’s curriculum Theatre Terms 18 packages. Theatre Etiquette 19 About Carousel Theatre for Young People 20 Our Sponsors 20 Contact Us! 21 2 Synopsis When the rambunctious boy Max is sent to bed without supper, he finds himself transported to a faraway island inhabited by mighty Wild Things. -

Seawright-Dissertation-2017

Bodies of Books: Literary Illustration in Twentieth Century Brazil The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945017 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Bodies of Books: Literary Illustration in Twentieth Century Brazil A dissertation presented by Max Ashton Seawright to The Department of Romance Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Romance Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January, 2017 © 2017 Max Ashton Seawright All rights reserved. Professor Josiah Blackmore Max Ashton Seawright Bodies of Books: Literary Illustration in Twentieth Century Brazil ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the nature and role of literary illustrations twentieth century Brazil, not just in relation to their companion texts, but also in what ways they reflect defining characteristics of Brazilian literature beyond the chronological or theoretical limits of modernism, regionalism, magic realism, or postmodernism. Illustrations in new fiction — that is, writer and artist and editor collaborating on a book to be illustrated in its first or otherwise definitive edition — gained popularity in Brazil just as the form waned from existence in North America and Europe, where the “Golden Age” of book illustration was a nineteenth century phenomenon. Understanding illustrated books is key to approaching Brazil’s artistic production beyond the strictly textual or visual. -

“The Art of the Picture Book,” by Mary Erbach (2008)

The Art of the Picture Book MARY M. ERbaCH PICTURE BOOKS at AN ART MUSEUM PROGRAMS WITH PICTURE BOOKS Once upon a time back in 1964 the Art Institute of Chicago Families visit the museum to learn, have fun, and spend time opened an education space called the Junior Museum, with together. Many children visiting the museum have been read galleries, studios, and a little library of picture books for visi- to their entire lives and have a book collection at home. They tors to enjoy. What foresight the planners had to include a may even be familiar with visits to the public library and room full of books for children at an art museum. Thus began have their own card. For our youngest audience (3–5-year- an era that still prevails almost a half century later. Speed olds), a museum visit might not be a common experience, ahead to 2007: a recent study with parents showed that the but it can be an exciting one. Museum educators understand family library is still a favorite destination. This cozy space is that the workshops and gallery walks need to be engaging a comfortable gathering spot where families can hang out and and interactive. Beginning with an activity that children are read, or where teachers can have some down time with their familiar with, such as reading a picture book, establishes a classes and share a story. It’s a great place for storytelling pro- comfort zone for young children who are in a strange big grams and for hosting book signings by guest illustrators. -

ILLUSTRATED BOOKS – August 2014

ILLUSTRATED BOOKS – August 2014 1. Porter, Gene Stratton. MUSIC OF THE WILD. Doubleday Page, Garden City. Second edition, with copyright date 1910, owner inscription with 1914 date. 8vo., stamped green cloth, t.e.g., 429pp., illustrated. Very good, with bottom edge very lightly rubbed, owner inscription on ffep $35.00 2. (Soper, George)illus. THE WATER BABIES by Charles Kingsley. Headley Bros., London, 1908. 8vo., 3/4 green calf gilt, 259pp., plus ad, 4 color plates, b/w illustrations. Very minor edge rubs, else Fine. $75.00 3. (Hassam, Childe)illus. ON LAND AND SEA or California in the Years 1843, '44 and '45 by William H. Thomes. [Howes, T-185."...authentic picture of California in the early 'forties comparable to Dana's classic narrative.] DeWolfe, Fiske, Boston, 1884 (1st ed). 12mo., decorated cloth, 351pp., illustrated. Originally published in Ballou's Monthly Magazine. Delicate line drawings as chapter headpieces; very early Hassam. A very nice copy, though lightly rubbed along extremities. $45.00 4. Delstanche, Albert. THE LEGEND OF THE GLORIOUS ADVENTURES OF TYL ULENSPIELGEL IN THE LAND OF FLANDERS AND ELSEWHERE by Charles De Coster. Chatto & Windus, London, 1918. Cloth, 301pp., illustrated with 20 woodcuts by Delstanche. VG $75.00 5. (JOB. Jacques Onfroy de Breville)illus. TROIS COULEURS - France, Son Histoire by G. Montorgueil. Paris, (n.d.) Folio, decorated cloth, narrative history of France with illustrations in delicate color lithography accompanying text on almost every page. One of JOB's masterworks. Covers somewhat rubbed, internally Fine. $125.00 6. (Neill, John R.)illus. THE MAGIC OF OZ by L. -

Profile of Illustration in Children's Literature Books Based on The

Beata Mazepa-Domagała Poland Profile of Illustration in Children’s Literature Books Based on the Image Preferences of the Youngest Readers DOI: 10.15804/tner.2017.49.3.18 Abstract The presented paper is a result of research conducted on the issue of visual communication as an art supplement and explanation of printed content. The publication begins with a reflection on visual culture illustrating its polysemic character and referring to the iconic nature of images. Further, the paper describes the art of illustration and the value of visual communication in the form of book illustration. The last part of the paper attempts to present the structure of a well-designed illustration in the form of profiles, constructed on the basis of picture tendencies appear in a group of pre-readers. Keywords: book illustration, visual communication, pre-school child Introduction Recent years have brought significant changes in widely understood culture, which today is undoubtedly of audiovisual nature. The emerging phenomenon in which visuality dominates over the word especially confirms that fact. The expansion of visual communication, visual external advertising, picture books, comics, the spread of audiovisual media – electronic sources of experience and the invasion of homogeneous – often trashy – mass culture as well as dominance of adult culture over the culture addressed to children in both the offer and reception are only some examples where this phenomenon may be observed. 224 Beata Mazepa-Domagała This state of affairs makes a person live in a world in which his or her daily exist- ence depends on certain impulses, pressures derived from visual stimuli and being accustomed to the surrounding images, he or she is unaware of their influence. -

Sendak's and Knussen's Intended Audiences of Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop!

CREATIVE DIFFERENCES: SENDAK’S AND KNUSSEN’S INTENDED AUDIENCES OF WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE AND HIGGLETY PIGGLETY POP! by Leah Giselle Field M.Mus., University of Western Ontario, 2008 B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) January 2015 © Leah Giselle Field, 2015 Abstract Author and illustrator Maurice Sendak and composer Oliver Knussen collaborated on two one- act operas based on Sendak’s picture books Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life. Though they are often programmed as children’s operas, Sendak and Knussen labeled the works fantasy operas, but have provided little commentary on any distinction between these labels. Through examination of their notes and commentary on the operas, published reviews and analysis of the operas, e-mail interviews conducted with operatic administrators and composers of children’s operas, and my analysis of the two works I intend to show that Sendak and Knussen had different target audiences in mind as they created these works. ii Preface This dissertation is an original intellectual product of the author, Leah Giselle Field, with the guidance of professors Dr. Alexander J. Fisher and Nancy Hermiston. The e-mail interviews discussed in Chapter II were covered by UBC Behavioral Research Board of Ethics Certificate number H12-03199 under the supervision of Principal Investigator Dr. Alexander J. Fisher. iii Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................................