Sendak's and Knussen's Intended Audiences of Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21 MARCH FRIDAY SERIES 11 Helsinki Music Centre at 19

21 MARCH FRIDAY SERIES 11 Helsinki Music Centre at 19 Oliver Knussen, conductor Leila Josefowicz, violin Kirill Gerstein, piano Hans Werner Henze: Barcarola 20 min INTERVAL 20 min Alban Berg: Chamber Concerto 39 min I Thema scherzoso con variazioni II Adagio III Rondo ritmico con introduzione Interval at about 19.30. The concert ends at about 20.45. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and the internet (yle.fi/klassinen). 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Petri Aarnio & Jari Valo, violin Riitta-Liisa Ristiluoma & Martta Tolonen, viola Tuomas Lehto & Mikko Ivars, cello Arnold Schönberg: Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) 28 min I Sehr langsam II Etwas bewegter III Schwer betont IV Sehr breit und langsam V Sehr ruhig 2 HANS WERNER ginning of the piece the Eton Boating Song from my opera We Come to the HENZE (1926–2012): River, can be heard briefly in the harps. BARCAROLA Later, after extended cantilenas, the real Barcarola is played by the solo vi- Hans Werner Henze was one of the ola, accompanied lightly by flutes and leading post-WWII composers in harps. In the score, the musical progress both his native Germany and Europe. is carried out like a journey: the musi- Barcarola was commissioned by the cal material is transformed, changed Tonhalle-Gesellschaft Zürich and and developed in the same sense as is was first performed there with Gerd the mental process of metamorphosis. Albrecht conducting in April 1980. -

Nagroda Im. H. Ch. Andersena Nagroda

Nagroda im. H. Ch. Andersena Nagroda za wybitne zasługi dla literatury dla dzieci i młodzieży Co dwa lata IBBY przyznaje autorom i ilustratorom książek dziecięcych swoje najwyższe wyróżnienie – Nagrodę im. Hansa Christiana Andersena. Otrzymują ją osoby żyjące, których twórczość jest bardzo ważna dla literatury dziecięcej. Nagroda ta, często nazywana „Małym Noblem”, to najważniejsze międzynarodowe odznaczenie, przyznawane za twórczość dla dzieci. Patronem nagrody jest Jej Wysokość, Małgorzata II, Królowa Danii. Nominacje do tej prestiżowej nagrody zgłaszane są przez narodowe sekcje, a wyboru laureatów dokonuje międzynarodowe jury, w którego skład wchodzą badacze i znawcy literatury dziecięcej. Nagrodę im. H. Ch. Andersena zaczęto przyznawać w 1956 roku, w kategorii Autor, a pierwszy ilustrator otrzymał ją dziesięć lat później. Na nagrodę składają się: złoty medal i dyplom, wręczane na uroczystej ceremonii, podczas Kongresu IBBY. Z okazji przyznania nagrody ukazuje się zawsze specjalny numer czasopisma „Bookbird”, w którym zamieszczane są nazwiska nominowanych, a także sprawozdanie z obrad Jury. Do tej pory żaden polski pisarz nie otrzymał tego odznaczenia, jednak polskie nazwisko widnieje na liście nagrodzonych. W 1982 roku bowiem Małego Nobla otrzymał wybitny polski grafik i ilustrator Zbigniew Rychlicki. Nagroda im. H. Ch. Andersena w 2022 r. Kolejnych zwycięzców nagrody im. Hansa Christiana Andersena poznamy wiosną 2022 podczas targów w Bolonii. Na długiej liście nominowanych, na której jest aż 66 nazwisk z 33 krajów – 33 pisarzy i 33 ilustratorów znaleźli się Marcin Szczygielski oraz Iwona Chmielewska. MARCIN SZCZYGIELSKI Marcin Szczygielski jest znanym polskim pisarzem, dziennikarzem i grafikiem. Jego prace były publikowane m.in. w Nowej Fantastyce czy Newsweeku, a jako dziennikarz swoją karierę związał również z tygodnikiem Wprost oraz miesięcznikiem Moje mieszkanie, którego był redaktorem naczelnym. -

Carols of the Nativity 7

Listen 2 Catalog No. 7.0457 Commissioned by the Canada Council and B. C. Arts Council for the Phoenix Chamber Choir,Vancouver, Dr. Ramona Luengen, director Carols of the Nativity 7. Angels We Have Heard On High for SSATBB Chorus and optional Piano or Organ Traditional (eighteenth century) Traditional arr. Stephen Chatman Joyously = c. 126-132 * Soprano An -gels we have heard on high, heard on Alto An -gels we have heard on high, heard on Tenor An -gels we, we have heard Bass An - gels we have heard Joyously = c. 126-132 Piano or Organ (optional) * The entire arrangement may be sung one-half step lower if unaccompanied. Publisher’s Note The seven titles in Carols of the Nativity are: 1. As I Lay Upon a Night (#7.0451) 2. Bring a Torch, Jeanette, Isabella (#7.0452) 3. The Huron Carol (#7.0453) 4. A Christmas Lullaby (#7.0454) 5. The First Noël (#7.0455) 6. Wassail (#7.0456) 7. Angels We Have Heard On High (#7.0457) Carols of the Nativity is also available with accompaniments for brass quintet (#7.0467 [score], #7.0468 [parts]) or orchestra. The former version is available for purchase and the latter version is available for rental from the publisher. © Copyright 2005 by Highgate Press. A division of ECS Publishing, Boston, Massachusetts. All rights reserved. Made in U.S.A. 3 Verse I 4 div. unis. cresc. S high, on high. An -gels we have heard on high Sweet-ly sing -ing cresc. A high on high. An -gels we have heard on high Sweet-ly sing -ing cresc. -

Poul Ruders Four Dances Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Oliver Knussen DACAPO 8.226028 POUL RUDERS (B

POUL RUDERS Four Dances Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Oliver Knussen DACAPO 8.226028 POUL RUDERS (b. 1949) Four Dances in One Movement (1983) 19:04 1 Whispering – 1:44 2 Rocking – 5:03 Four Dances 3 Ecstatic – 3:52 4 Extravagant 8:25 Birmingham Contemporary Music Group Oliver Knussen, conductor 5 Nightshade (1987) 8:35 Marie-Christine Zupancic | flute, piccolo, alto Abysm (2000) 23:32 Melinda Maxwell | oboe * 6 I Abysm 12:32 Rebecca Kozam | oboe, cor anglais ** 7 II Burning 1:48 Joanna Patton | clarinet ** 8 III Spectre 9:09 Mark O’Brien | clarinet, bass clarinet *, contra bass clarinet ** Margaret Cookhon | bassoon, contra bassoon ** Total: 51:08 Mark Phillips | horn Jonathan Holland | trumpet Alan Thomas | trumpet * Ed Jones | trombone Julian Warburton | percussion 1 Adrian Spillett | percussion 2 Malcolm Wilson | piano Alexandra Wood | violin 1 Gabriel Dyker | violin 2 ** Christopher Yates | viola Ulrich Heinen | cello John Tattersdill | double bass * Abysm ** Four Dances; Nightshade Dacapo is supported by the Danish Arts Council Committee for Music POUL RUDERS (b. 1949) Four Dances in One Movement (1983) 19:04 1 Whispering – 1:44 2 Rocking – 5:03 Four Dances 3 Ecstatic – 3:52 4 Extravagant 8:25 Birmingham Contemporary Music Group Oliver Knussen, conductor 5 Nightshade (1987) 8:35 Marie-Christine Zupancic | flute, piccolo, alto Abysm (2000) 23:32 Melinda Maxwell | oboe * 6 I Abysm 12:32 Rebecca Kozam | oboe, cor anglais ** 7 II Burning 1:48 Joanna Patton | clarinet ** 8 III Spectre 9:09 Mark O’Brien | clarinet, bass clarinet -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Women of Distinction Awards Nominees 1984

YWCA WOMEN OF DISTINCTION AWARDS NOMINEES AND RECIPIENTS 1984 - 2020 NOMINEES AND RECIPIENTS YEAR CATEGORY Anna Wyman 1984 Arts & Culture Lucille Johnstone 1984 Business Shirley Stocker 1984 Communications Kate Schurer 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Pat Carney 1984 Government & Public Affairs Verna Splane 1984 Health, Education & Recreation Ann Mortifee 1984 Arts & Culture Anna Wyman 1984 Arts & Culture Elizabeth Ball 1984 Arts & Culture Jean Coulthard Adams 1984 Arts & Culture Marjorie Halpin 1984 Arts & Culture Nini Baird 1984 Arts & Culture Wilma Van Nus 1984 Arts & Culture Barbara Rae 1984 Business Bruna Giacomazzi 1984 Business Doreen Braverman 1984 Business Nancy Morrison 1984 Business Elizabeth Chapman 1984 Communications & Public Affairs Anna Terrana 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Barbara Brink 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Carole Fader 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Douglas Stewart 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Eleanor Malkin 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Joan Williams 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Lucille Courchene 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Margaret Ramsay 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Martha Lou Henley 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Rhoda Waddington 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Rita Morin 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Ruth Cash 1984 Community & Humanitarian Service Dorothy Goresky 1984 Government & Public Affairs Hilde Symonds 1984 Government & Public Affairs Joan Wallace 1984 Government & Public Affairs Lois Bayce 1984 Government -

Curriculum Guide 5Th - 8Th Grades

Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are, © 1963 by Maurice Sendak, all rights reserved. Curriculum Guide 5th - 8th Grades In a Nutshell:the Worlds of Maurice Sendak is on display jan 4 - feb 24, 2012 l main library l 301 york street In a Nutshell: The Worlds of Maurice Sendak was organized by the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia, and developed by Nextbook, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting Jewish literature, culture, and ideas, and the American Library Association Public Programs Office. The national tour of the exhibit has been made possible by grants from the Charles H. Revson Foundation, the Righteous Persons Foundation, the David Berg Foundation, and an anonymous donor, with additional support from Tablet Magazine: A New Read on Jewish Life. About the Exhibit About Maurice Sendak will be held at the Main Library, 301 York St., downtown, January 4th to February 24th, 2012. Popular children’s author Maurice Sendak’s typically American childhood in New York City inspired many of his most beloved books, such as Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. Illustrations in those works are populated with friends, family, and the sights, sounds and smells of New York in the 1930s. But Sendak was also drawn to photos of ancestors, and he developed a fascination with the shtetl world of European Jews. This exhibit, curated by Patrick Rodgers of the Rosenbach Museum & Library Maurice Sendak comes from Brooklyn, New York. in Philadelphia, reveals the push and pull of New and Old He was born in 1928, the youngest of three children. -

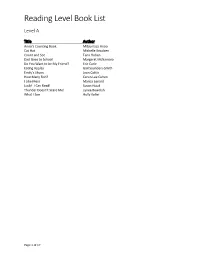

Book List by Reading Level

Reading Level Book List Level A Title Author Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anoo Cat Hat Michelle Knudsen Count and See Tana Hoban Dad Goes to School Margaret McNamara Do You Want to be My Friend? Eric Carle Eating Apples Gail Saunders-Smith Emily’s Shoes Joan Cottle How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen I Like Mess Marcia Lenard Look! I Can Read! Susan Hood Thunder Doesn’t Scare Me! Lynea Bowdish What I See Holly Keller Page 1 of 17 Reading Level Book List Level B Title Author Bravo, Kazam! Amy Ehrlich Eddie the Raccoon Catherine Friend Ethan at Home Johanna Hurwitz Get the Ball, Slim Marcia Leonard Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle How Many Fish? Caron Cohen I Love My Family Joy Cowley Larry and the Cookie Becky McDaniel The Long, Long Tail Joy Cowley Mommy, Where are you? Leonid Gore Major Jump Joy Cowley Mouse has Fun Phyllis Root My Puppy Joy Cowley Piggy and Dad Go Fishing David Martin Snap! Joy Cowley Page 2 of 17 Reading Level Book List Level C Title Author Along Comes Jake Joy Cowley The Best Place Susan Meddaugh Big and Little Joy Cowley Brown Bear, Brown Bear Bill Martin, Jr. Bugs! Pat McKissack Bunny, Bunny Kirsten Hall A Hug is Warm Joy Cowley I Went Walking Sue Williams Ice Cream Joy Cowley I’m Bigger Than You! Joy Cowley Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie Let’s Have a Swim Joy Cowley Little Brother Joy Cowley One Hunter Pat Hutchins Our Granny Joy Cowley Our Street Joy Cowley Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie DePaola The Race Joy Cowley Rainbow of My Own Don Freeman Spots, Feathers and -

The John Newbery Medal

NEWBERY AWARD WINNERS 1922 – 2015 Distinguished Contribution to American Literature for Children 2015 Winner: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander Honor Books: El Deafo by Cece Bell Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson 2014 Winner: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo Honor Books: Doll Bones by Holly Black The Year of Billy Miller by Kevin Henkes One Came Home by Amy Timberlake Paperboy by Vince Vawter 2013 Winner: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate Honor Books: Splendors and Glooms by Laura Amy Schiltz Bomb: the Race to Build—and Steal—the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin Three Times Lucky by Sheila Turnage 2012 Winner: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos Honor Books: Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai Breaking Stalin's Nose by Eugene Yelchin 2011 Winner: Moon over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool Honor Books: Turtle in Paradise by Jennifer L. Holm Heart of a Samurai by Margi Preus Dark Emperor and Other Poems of the Night by Joyce Sidman One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia 2010 Winner: When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead Honor Books: Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice by Phillip Hoose The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate by Jacqueline Kelly Where the Mountain Meets the Moon by Grace Lin The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg by Rodman Philbrick 2009 Winner: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman Honor Books: The Underneath by Kathi Appelt The Surrender Tree: Poems of Cuba's Struggle for Freedom by Margarita Engle Savvy by Ingrid Law After Tupac & D Foster by Jacqueline Woodson 2008 Winner: Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schiltz Honor Books: Elijah of Buxton by Christopher Paul Curtis The Wednesday Wars by Gary D. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews Ligeti Le Grand Macabre (Prince Go-Go), Semperoper Dresden (November 2019) Counter Christopher Ainslie [w]as a wonderfully infantile Prince Go-Go ... [The soloists] master their games as effortlessly as if they were singing Schubertlieder. - Christian Schmidt, Freiepresse A multitude of excellent voices [including] countertenor Christopher Ainslie as Prince with pure, blossoming top notes and exaggerated drama they are all brilliant performances. - Michael Ernst, neue musikzeitung Christopher Ainslie gave a honeyed Prince Go-Go. - Xavier Cester, Ópera Actual Ainslie with his wonderfully extravagant voice. - Thomas Thielemann, IOCO Prince Go-Go, is agile and vocally impressive, performed by Christopher Ainslie. - Björn Kühnicke, Musik in Dresden Christopher Ainslie lends the ruler his extraordinary countertenor voice. - Jens Daniel Schubert, Sächsische Zeitung Christopher Ainslie[ s] rounded countertenor, which carried well into that glorious acoustic. - operatraveller.com Handel Rodelinda (Unulfo), Teatro Municipal, Santiago, Chile (August 2019) Christopher Ainslie was a measured Unulfo. Claudia Ramirez, Culto Latercera Handel Belshazzar (Cyrus), The Grange Festival (June 2019) Christopher Ainslie makes something effective out of the Persian conqueror Cyrus. George Hall, The Stage Counter-tenors James Laing and Christopher Ainslie make their mark as Daniel and Cyrus. Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph Ch enor is beautiful he presented the conflicted hero with style. Melanie Eskenazi, MusicOMH Christopher Ainslie was impressive as the Persian leader Cyrus this was a subtle exploration of heroism, plumbing the ars as well as expounding his triumphs. Ashutosh Khandekar, Opera Now Christopher Ainslie as a benevolent Cyrus dazzles more for his bravura clinging onto the side of the ziggurat. David Truslove, OperaToday Among the puritanical Persians outside (then inside) the c ot a straightforwardly heroic countertenor but a more subdued, lighter and more anguished reading of the part. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite .