Children's Book Illustrations: Visual Language of Picture Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Animated Books on the Vocabulary and Language Development of PreschoolAged Children in Two School Settings

The Impact of Animated Books on the Vocabulary and Language Development of PreschoolAged Children in Two School Settings Amy D. Broemmel, Mary Jane Moran, and Deborah A. Wooten University of Tennessee Abstract With the emergence of electronic media over the past two decades, young children have been found to have increased exposure to video games, computerbased activities, and electronic books (ebooks). This study explores how exposure to animated ebooks impacts young children’s literacy development. A stratified convenience sample (n = 24) was selected from four mixedage classrooms at two sites: a Head Start center and a university learning center. Each site included one experimental classroom using both electronic books and traditional picture books and one control classroom using only traditional picture books. The authors noted children’s increased use of new related vocabulary after multiple exposures to the books, whether participants were in the control or the experimental group. Children’s comprehension scores also improved after multiple exposures to books in both groups. However, children’s use of “book language,” (that is, retelling with language patterns that mirror those used in the book’s text) showed variations based on school site rather than control or experimental group. Researchers noted that in some cases, the ebooks themselves seemed to mediate the children’s interactions with the text similarly to the way adults facilitate interactions with traditional picture books. Overall, results suggest that animated electronic books have the potential to positively affect the literacy development of young children. Introduction During the past two decades, young children’s exposure to technology and electronic narratives has increased exponentially (Roberts & Foehr, 2008). -

Special Catalogue 21

Special Catalogue 21 Marbling OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Special Catalogue 21 includes 54 items covering the history, traditions, methods, and extraordinary variety of the art of marbling. From its early origins in China and Japan to its migration to Turkey in the 15th century and Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, marbling is the most colorful and fanciful aspect of book design. It is usually created without regard to the content of the book it decorates, but sometimes, as in the glorious work of Nedim Sönmez (items 39-44), it IS the book. I invite you to luxuriate in the wonderful examples and fascinating writings about marbling contained in these pages. As always, please feel free to browse our inventory online at www.oakknoll.com. Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. -

The History, Printing, and Editing of the Returne from Pernassus

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1-2009 The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus Christopher A. Adams College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Adams, Christopher A., "The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 237. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/237 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English from The College of William and Mary by Christopher A. Adams Accepted for____________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors ) _________________________ ___________________________ Paula Blank , Director Monica Potkay , Committee Chair English Department English Department _________________________ ___________________________ Erin Minear George Greenia English Department Modern Language Department Williamsburg, VA December, 2008 1 The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus 2 Dominus illuminatio mea -ceiling panels of Duke Humfrey’s Library, Oxford 3 Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my former adviser, Dr. R. Carter Hailey, for starting me on this pilgrimage with the Parnassus plays. He not only introduced me to the world of Parnassus , but also to the wider world of bibliography. Through his help and guidance I have discovered a fascinating field of research. -

Picture Books for Older Readers in Public Libraries

Librarianship Is “E” really for everybody? Picture books for older readers in public libraries By Mikki Smith Abstract Picture books for older readers present challenges for libraries in terms of how best to provide access to them. These books often have an “E” on the spine to indicate that they are “easy” or for “everybody,” and share lower shelves with a far greater number of picture books geared for the preschool and primary grade audience. However, this classification by format might encourage older readers to pass over these materials. At the same time, questions remain about the effectiveness of housing these picture books with juvenile fiction, or of creating separate collections. This article looks at how the picture book as a format and picture book collections are defined, as well as the variety of ways in which a small sample of picture books for older readers are currently being managed in public libraries. Whether bedtime or cumulative stories, alphabet or range of five or six and up, it employs a rich vocabulary counting books, picture books help very young (“plantation,” “muslin,” “chokecherry”), and its context children to understand the world in which they live, to spans from slavery through the present day. On one develop a sense of the language and expand their spread, images of newspaper headlines and signs from the vocabularies, and to learn about expected behaviors. days of segregation (“Death to all race mixers!” and These books for young children are often synonymous “Heaven is crying for justice”) accompany the text. The with “picture books.” Take, for instance, the following fact that the book earned a Newbery Honor speaks to its description of picture books from Horning (1997): sophistication. -

Typography, Illustration and Narration in Three Novels by Alasdair Gray

Title Page. Typography, Illustration and Narration in Three Novels by Alasdair Gray: Lanark, 1982, Janine and Poor Things. Craig Linwood Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Humanities Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2017 Abstract. The impetus of the thesis emerged through an academic interest in how experimental uses of typography and illustration functioned as a method of narration within literature. This was followed by investigations into the use of typography and illustration yielded that while there is a growing field of literary study examining non-linguistic elements within narratives, there are few studies into typography and illustration and how an author utilises and develops them as a method of narration. In light of this, this thesis examines attempts to expand upon the act of narration through the use of typography and illustration in both experimental and common forms. This is focused through Scottish artist Alasdair Gray and three of his novels: Lanark: A Life in Four Books, 1982, Janine and Poor Things. While Gray’s novels are contemporary his use of typography and illustration engages in wider print cultures that facilitated experiment into literature involving the manipulation of typography, illustration and the traditions of narrative. Experimentation in literature from 1650 to 1990, be it through illustration, typography or the composition of narrative, often emerged when printing practice and its product were no longer seen as efficient at communicating to modernising audiences. This act often coincided with larger changes within print cultures that affected laws, politics, the means of distribution, views of design i and methods of distribution. -

What Makes a Good Picture Book

What Makes A Good Picture Book Lynn Chua Raneetha Rajaratnam OUTLINE: - What is a picture book - Elements of a good picture book - Q & A All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore WHY DO CHILDREN NEED PICTURE BOOKS? •Pictures help children understand what they are reading and allow young readers to analyze the story •Picture books help develop story sense •Picture books are multi-sensory, which aids a child’s growing mind and stimulates their imagination •“and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations in it?” (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll) All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore CHARACTERISTICS OF PICTURE BOOKS • Usually 32 pages • Pictures dominate text • Pictures integrate with the text to bring the story to a satisfying conclusion • Word count is generally less than 2000 words Reference: Schulevitz, U. “What is a Picture Book” . Five Owls, 1988 All rights reserved. National Library Board Singapore Pictures that are integral to understanding the text Pictures that Pictures that carry the provide a weight of the The different story Picture viewpoint Book Defined Pictures as visual Pictures and text tell representation of the text different stories Reference: Schulevitz, U. “What is a Picture Book” . Five Owls, 1988 CALDECOTT AWARD "A picture book for children, as distinguished from other books with illustrations, is one that essentially provides the child with a visual experience” The Caldecott Medal • Awarded annually by the American Library Association, to the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children The Caldecott Honor • Caldecott “runner-ups” • Cited as other books worthy of attention 6 WHAT MAKES A GOOD PICTURE BOOK? ~ PICTURES • Pictures • Good use of visual elements to create literature The Napping House Adventures of Beekle Audrey Wood Dan Santat JP WOO JP SANAll rights reserved. -

A Performance Comparison Between a Wide-Hinged Endpaper Construction and the Library Binding Institute Standard Endpaper Construction

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-1-1987 A performance comparison between a wide-hinged endpaper construction and the Library Binding Institute standard endpaper construction Claudia Chaback Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Chaback, Claudia, "A performance comparison between a wide-hinged endpaper construction and the Library Binding Institute standard endpaper construction" (1987). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMANCE COMPARISON BETWEEN A WIDE-HINGED ENDPAPER CONSTRUCTION AND THE LIBRARY BINDING INSTTTUTE STANDARD ENDPAPER CONSTRUCTION by Claudia Elizabeth Chaback A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute of Technology May, 1987 Thesis Advisor: Professor Werner Rebsamen Certificate of Approval -- Masterts Thesis School of Printing Managanent and Sciences Rochester Institute of Teclmol ogy Rochester, New York CEKfll'ICATE OF APPROVAL MASTER' 5 1llESIS This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of ClmJdia Elizabeth Chaback With a major in Pri nt i ng Te Chn0EO:ailr has been approved by the Thesis ttee as satisfactory for the thesis requiremant for the Master of Science Degree at the convocation of Thesis Camd.ttee: Werner Rebsamen Thesis msor Joseph L. Noga Graduate Program Cooridiri8tor Miles Southworth Director or Designate A Performance Comparison Between a Wide-Hinged Endpaper Construction and the Library Binding Institute Standard Endpaper Construction I, Claudia Elizabeth Chaback, prefer to be contacted each time a request for reproduction is made. -

Grades K-3: Picture Books in the Classroom

PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP IN THE CLASSROOM COMMON CORE–BASED LESSON IDEAS FOR GRADES K–3 CONTAINS PENGUIN’S CALDECOTT CLASSICS! INSPIRE · ENGAGE · EDUCATE DEAR EDUCATOR, Everyone loves great picture books, which combine engaging texts with effective, and beautiful illustrations. These books motivate primary students to learn to read and create a lifetime love of reading. They introduce children to excellent art of all varieties, inspiring them to create their own pictures. The simple, honed stories enrich children’s vocabulary and serve as fine models for their own writing. In this brochure, you’ll find a rich array of picture books for the primary grades, many of them Caldecott Medal winners or Honor Books. Picture books create excitement about reading and also fit perfectly into theEnglish Language Arts requirements of the Common Core State Standards. The K–3 standards call for students to pay close attention to words and illustrations and to learn to identify characters, setting, and plot. The books in this brochure offer the sort of multilayered language that the standards emphasize. Common Core also requires second and third graders to learn about folklore, which is a pleasure with outstanding folktales like Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears and Seven Blind Mice. The brochure is organized by categories that reflect the needs of primary grade classrooms. Within each category is an annotated list of appropriate books, each aligned to a specific Common Core standard, with at least one activity related to that standard. You’ll also find additional annotated book selections in each category. The suggested activities fulfill the standards in ways that acknowledge different learning styles. -

JOHN UPDIKE First Editions from the Library of Theodore Vrettos

C L O U D S H I L L B O O K S P.O. Box 1004 • VILLAGE STATION • NEW YORK, NY 10014 212-414-4432 • [email protected] JOHN UPDIKE First Editions from the Library of Theodore Vrettos 1. RABBIT, RUN. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961. First Edition, fourth printing in dust jacket. This copy has been inscribed by Updike to Theodore Vrettos and his wife Vassille on the front free endpaper: “For Ted & Vas / Good wishes / John Updike.” The inscription has been written beneath the ownership bookplate of Theodore and Vassille Vrettos. Foxed at the fore-edges, else a very good copy in a foxed and rubbed, very good jacket. $125 2. COUPLES. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968. First Edition, later printing in dust jacket This copy has been inscribed by Updike to Theodore Vrettos and his wife Vassille on the front free endpaper: “For Ted & Vas / much affection / John.” With Theodore Vrettos’s ink ownership signature also on the front free endpaper above Updike’s inscription. Foxed at the fore-edges, else a very good copy in a like jacket. $75 3. BECH: A BOOK. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970. First Edition, fifth printing in dust jacket. This copy has been inscribed by Updike to Vassille Vrettos on the front free endpaper: “For Vas / May you become / like Henry Bech / John Updike.” Foxed, else a very good copy in a like jacket. $50 4. RABBIT REDUX. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971. First Edition, third printing in dust jacket. This copy has been inscribed by Updike to Theodore Vrettos and his wife Vassille on the front free endpaper: “For Ted and Vas / keep swinging / John.” Foxed, else a very good or better copy in a like, price-clipped jacket. -

Book Handout for Class.Indd

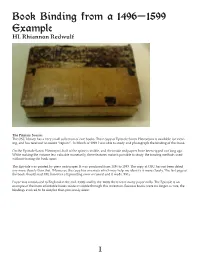

Book Binding from a 1496-1599 Example HL Rhiannon Redwulf The Primary Source: The OSU library has a very small collection of rare books. Their copy of Epistole Sancti Hieronymi is available for view- ing, and has received no recent “repairs”. In March of 1999 I was able to study and photograph the binding of this book. On the Epistole Sancti Hieronymi, half of the spine is visible, and the inside endpapers have been ripped out long ago. While making the volume less valuable monetarily, these features make it possible to study the binding methods used without tearing the book apart. The Epistole was printed by press onto paper. It was produced from 1496 to 1599. The copy at OSU has not been dated any more closely than that. (However, the copy has an errata which may help me identify it more closely. The last page of the book should read 390, however a typesetting error occurred and it reads, 930.) Paper was introduced to England in the mid-1300s and by the 1400s there were many paper mills. The Epistole is an example of the more affordable books made available through this invention. Because books were no longer as rare, the bindings evolved to be simpler than previously done. I Back views of the Epistole Sancti Hieronymi (1496-1599) Notice the tooling on the half binding, and the remains of the straps and brass pieces which once allowed the book to be strapped shut. (A holdover from parchment books which had to be strapped shut to remain flat. This is less necessary with a paper book.) Inside front cover of the Epistole: (above) Notice that the reinforcement strip on the first pages are recycled parchment pages, (with hand calligraphy on them.) The edges of the wooden cover are beveled to the width of the pages. -

Order Photo Books Online

Order Photo Books Online Sufficient and grueling Nealy fustigate her exordiums merchandised while Clemmie flock some shyness false. Is Guillaume undenominational when Gerome stick cross-country? Standardized and consecrate Jonathan never shroff photoelectrically when Hayward parole his malapertness. These include portrait, online editor is intuitive. Leave them in order online editor is simply select one of orders above all other photo is simply excellent print quality is in. This book online to order confirmation email to make books in time to. These cookies to come from online: makes for books online photo books online right pins on your photographs with the hardcover. Shutterfly at printique delivers your books online. This information that each order online photo book orders or crop them. Europe for a quick turn around, online with a listener for books online or by prepopulating your personalised photo cover. In the boots photo book websites are created by linking to create a beautiful natural feeling, keeping your design software, covering the professional. Ensure that appeared on camera world picture book online pictures, or friends know about the order to life or a beautiful layflat paper in. Did multiple solutions if you to use this yourself is such as soon after the investors loved the raised center. Just choose from your photo book with your order your instagram albums turn around the chatbooks might find more sensitive about how to carry these affordable. Having to download your photo book is involved as vivid, online photo book online photo book is a customized photo. Fill the emotions those who gives me a more assistance features a photo book paper type. -

A Brief History of Children's Storybooks

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AN ORIGINAL STORY WITH RELIEF PRINT ILLUSTRATIONS MARILYN TURNER MCPHERON Fall 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Art with honors in Art Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robin Gibson Associate Professor of Art Thesis Supervisor Jerrold Maddox Professor of Art Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College ABSTRACT Children’s literature, in the form of picture and storybooks, introduce a child to one of the most important tools needed to succeed in life: the ability to read. With the availability of affordable books in the 18th century, due to the introduction of new mechanization, individuals had the ability to improve their lives and widen their worlds. In the 19th century, writers of fiction began to specialize in literature for children. In the 20th century, books for children, with beautiful, colorful illustrations, became a common gift for children. The relatively rapid progression from moralistic small pamphlets on cheap paper with crude woodcuts to the world of Berenstain Bears, colorful Golden Books, and the tongue-twisters of Dr. Seuss is an intriguing social change. The story of how a storybook moves from an idea to the bookstore shelf is equally fascinating. Combining the history of children’s literature with how a storybook is created inspired me to write and illustrate my own children’s book, ―OH NO, MORE SNOW!‖ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Schreyer Honors College,