A. Bullfighting in Ulysses Proofed And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Rezension Von: Michael Groden: Ulysses in Progress: Princeton, 1977

James Joyce Quarterly University of Tulsa Tulsa, Oklahoma 74104 THOMAS F. STALEY Editor FRITZ SENN . European Editor CHARLOTTE STEWART Managing Editor ALAN M. COHN ... Bibliographer MARK DUNPHY, CURTIS COTTRELL, CORINNA DEL GRECO LOBNER Graduate Assistants ADVISORY EDITORS James R. Baker, San Diego State University, California; Bernard Benstock, University of Illinois; Heimet Bonheim, University of Cologne; Robert Boyle, S.J., Marquette University; Edmund Epstein, Queens College; Bernard Fleischmann, Montclair State College; Hans Walter Gabler, University of Munich; Arnold Goldman, University of Keele; Nathan Halper; Clive Hart, University of Essex; David Hayman, University of Wisconsin; Phillip Herring, University of Wisconsin; Fred Higginson, Kansas State University; Richard M. Kain, University of Louisville; Hugh Kenner, The Johns Hopkins University; Leo Knuth, University of Utrecht; A. Walton Litz, Princeton University; Vivian Mercier, University of California, Santa Barbara; Margot C. Norris, University of Michigan; Darcy O'Brien, University of Tulsa; Joseph Prescott, Wayne State University; Hugh Staples, University of Cincinnati; Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina. Single Copy Price $3.00 (U.S.); $3.50 (foreign) Subscription Rates United States Elsexvhere 1 year 2 years 3 years 1 year 2 years 3 years Individuais: $10.00 $19.50 $29.00 $11.00 $21.50 $32.00 Institutions: 11.00 21.50 32.00 12.00 23.50 35.00 Send subscription inquiries and address changes to James Joyce Quarterly, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK 74104. Claims for back issues will be honored for three months only. All back issues except for the current volume may be ordered from Swets & Zeitlinger, Heereweg 347b, Lisse, The Netherlands, or P.O. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

The Maternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: the Subversive Molly Bloom

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-29-2019 The aM ternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: The Subversive Molly Bloom Arthur Moore Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Moore, Arthur, "The aM ternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: The ubS versive Molly Bloom" (2019). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 138. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/138 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MATERNAL BODY OF JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES: The Subversive Molly Bloom By Arthur Jacqueline Moore Submitted for Honors in Independent Study Spring 2019 I hereby reaffirm the Lawrence University Honor Code. Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 One: The Embodiment of the Maternal Character..................................................... 6 To Construct a Body within an Understanding of Male Dublin ................................................. 7 A Feminist Critical Interrogation of the Vital Fiction of Paternity ........................................... 16 Constructing the Maternal Body in Mary Dedalus and Molly Bloom ..................................... -

The Late Drafts of James Joyceand Malcolm Lowry

WOMEN'SVOICES: THE LATE DRAFTS OF JAMES JOYCEAND MALCOLM LOWRY Sue Vice University ofsheffield This is an examination of points of comparison between the works of James Joyce and Malcolm Lowry in tenns of their pre-publication revisions to their central female characters: Yvonne in Under the Volcano, Molly Bloom in Uiysses. Do Lowry and Joyce have methods of revision in common? Are these women characters affected by such revisions in similar ways? Do they become 'freer' and more dialogmd, in Mikhail Bakhtin's tenns, or is there a negative connection between their linguistic gender and the author's masculinity, the wielding of a blue pen over a textual b*?' And Wy, how do such pre-publication revisions affect the textual construction of femininity which we md in the published form? Can a case be made for such authorial transvestism actually putting into question accepted gender roles, voices and behaviour patterns? To start with Under the Volcano,in Yvonne's case a drama occurs in the five full drafts which Lowry produced over ten years2 It could be seen as Oedipal: the dnuiken Consul's daughter becomes the alcoholic Consul's wife; Hugh, the daughter's boyfriend, becomes the Consul's half-brother and possibly adulterous lover of Yvonne; and Laruelle looms increasingly larger, ñrst as a hoverer over the Consul's daughter, then as another possible lover of his wife. However, what Yvonne's metamorphosis fkom daughter to wife also shows is, ñrst, how Lowry's pracíice involved progressively casíing off the conventional intnisive narrator and allowing the characters to speak for themselves, so that, as Bakhtin would say: "we have a pluraiity of consciousnesses, with equal rights, each with its own world" (Bakhtin 1984, 104). -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2013 Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Barbara Nelson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nelson, Barbara, "Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 491. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/491 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTING ON NICELY IN THE DARK: THE PERILS AND REWARDS OF ANNOTATING ULYSSES By BARBARA LYNN HOOK NELSON B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, 1983 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School John Hunt, Chair Department of English Bruce G. Hardy Department of English Yolanda Reimer Department of Computer Science © COPYRIGHT by Barbara Lynn Hook Nelson 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Nelson, Barbara, M.A., December 2012 English Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Chairperson: John Hunt The problem of how to provide useful contextual and extra-textual information to readers of Ulysses has vexed Joyceans for years. -

The Yale Epiphanies: a New Typescript Sangam Macduff University of Geneva

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 17 (Spring 2017) The Yale Epiphanies: A New Typescript Sangam MacDuff University of Geneva I recently discovered a typescript of Joyce’s epiphanies amongst the Eugene and Maria Jolas papers at Yale (GEN MS 108.XV.64.1503). The typescript was not reproduced in the James Joyce Archive, is not listed in Michael Groden’s Index of Joyce’s manuscripts, and appears to have escaped the Joycean radar. Although it does not contain any new epiphanies, this late, careful copy of nineteen holograph epiphanies sheds light on a number of intriguing features of Joyce’s early work, whilst forcing us to revise some of our most commonplace assumptions about them. Indeed, the unexpected discovery of this typescript reminds us how little is known about Joyce’s epiphanies with any certainty. Around 1901 or 1902, Joyce began writing a series of short texts he called “Epiphany” or “Epiphanies,” with or without the capital (L II 28, 78; cf. L II 35). On 8 February 1903, he told Stanislaus “my latest additions to ‘Epiphany’ might not be to [Russell's] liking” [L II 28]); his inverted commas indicate that, initially at least, Joyce thought of “Epiphany” as a unified collection with a title.1 By March 1903, work on the collection was well underway, and Joyce clearly had an order in mind, since he told Stanislaus that he had “written fifteen epiphanies – of which twelve are insertions and three additions” (L II 35). This implies an ordered series, which is corroborated by Stanislaus Joyce’s recollection that “two or three months after” May Joyce’s death (August 13 1903) he found epiphany 21 “added to my brother’s series of epiphanies” (MBK 235). -

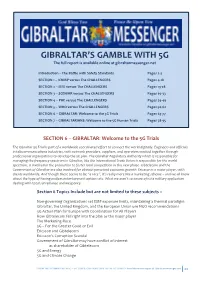

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but -

Molly Vs. Bloom in Midnight Court James Joyce Quarterly 41: 4

1 Joyce’s Merrimanic Heroine: Molly vs. Bloom in Midnight Court James Joyce Quarterly 41: 4 (Summer 2004): 745-65 James A. W. Heffernan In 1921, just one year before Ulysses first appeared, T.S. Eliot wrote the prescription for the kind of writer--Eliot’s word was “poet”--who would be required to produce it. He--male of course-- must bring to his work a “historical sense,” a capacity to integrate the life and literature of “his own generation” and “his own country” with “the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer” onward.12 Ulysses manifests Joyce’s command of that tradition on almost every page. Besides initiating a radically modern retelling of The Odyssey in a language that includes scraps of Greek, Latin, and French (with bits of German and Italian to come), the very first chapter of the novel spouts Homeric epithets, references to ancient Greek history and rhetoric, Latin passages from the Mass and Prayers for the Dying, allusions to Dante’s Commedia and Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and quotations from Hamlet and Yeats’s Countess Cathleen. Yet conspicuous by its absence from this multi-cultural stew is anything explicitly Gaelic, anciently Irish.3 Standing by the parapet of a tower built by the English in the late eighteenth century to keep the French from liberating Ireland, Stephen hears Mulligan’s proposal to “Hellenise” the island now (1.158) with something less than nationalistic fervor or Gaelic fever running through his head. “To ourselves . new paganism . omphalos,” he thinks (U 1.176). With “to ourselves” he alludes to Sinn Fein, meaning “We Ourselves,” the Gaelic motto of a movement that was founded in the 1890s to revive Irish language and culture and that became about 1905 the name of a political movement which remains alive and resolutely--if not militantly--nationalistic to this very day. -

AN ANALYTICAL and DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY STUDY of MEDIAEVAL ENGLISH DOCUMENTATION Elena Alfaya

The Grove P. 1 The Grove P. 3 The Grove Working Papers on English Studies Número 12 2005 Grupo de Investigación HUM. 0271 de la Junta de Andalucía The Grove P. 4 THE GROVE, WORKING PAPERS ON ENGLISH STUDIES Editor Concepción Soto Palomo Assistant Editor Yolanda Caballero Aceituno General Editor Carmelo Medina Casado Editorial Board J. Benito Sánchez, E. Demetriou, J. Díaz Pérez, M. C. Garrido Hornos, J. A. George, A. Lázaro Lafuente, J. López-Peláez Casellas, N. McLaren, J. M. Nieto García, E. Olivares Medina, J. Olivares Medina, N. Pascual Soler, J. Ráez Padilla, J. Talvet, B. Valverde Jiménez Scientific Board Juan Fernández Jiménez (Penn State University) Francisco García Tortosa (University of Sevilla) J. A. George (University of Dundee) Santiago González Fernández-Corugedo (University of Oviedo) Miguel Martínez López (University of Valencia) Gerardo Piña Rosales (City University of New York) Fred C. Robinson (Yale University) James Simpson (University of Cambridge) Jüri Talvet (Universidad de Tartu, Estonia) Style Supervisor Elizabeth Anne Adams Edita ©: Grupo de Investigación Hum. 0271 de la Junta de Andalucía Front cover design: David Medina Sánchez Diseño de cubierta: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Jaén Depósito Legal: J-689-2005 I.S.S.N.: 1137-00SX Indexed in MLA and CINDOC Difusión: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Jaén Vicerrectorado de Extensión Universitaria Paraje de Las Lagunillas, s/n - Edificio 8 23071 JAÉN Teléfono 953 21 23 55 Impreso por: Gráficas “La Paz” de Torredonjimeno, S. L. Avda. de Jaén, s/n 23650 TORREDONJIMENO (Jaén) Teléfono 953 57 10 87 - Fax 953 52 12 07 The Grove P. -

Wednesday 17Th March 2021

P R O C E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.40 p.m. – 7.40 p.m. Gibraltar, Wednesday, 17th March 2021 Contents Questions for Oral Answer ..................................................................................................... 3 Employment, Health and Safety and Social Security........................................................................ 3 Q519/2020 Health and safety inspections at GibDock – Numbers in 2019 and 2020 ............. 3 Q520/2020 Maternity grants and allowances – Reason for delays in applications ................. 3 Q521/2020 Carers’ allowance – How to apply ......................................................................... 5 Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change and Education .......................................................... 6 Q547/2021 Dog fouling – Number of fines imposed ................................................................ 6 Q548-50/2020 Barbary macaques – Warning signs and safety measures ............................... 7 Q551/2020 Governor’s Street – Tree planting ......................................................................... 8 Q552/2020 School buses – Rationale for cancelling ................................................................ 9 Q553/2020 Fly tipping – Number of complaints and prosecutions ......................................... 9 Q554/2020 Waste Treatment Plan – Update ......................................................................... 11 Q555/2020 Water production – Less energy-intensive