The Annotated “Nyarlathotep”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lovecraft Research Paper Final Draft

Nagelvoort 1 Chris Nagelvoort Professor Walsh Humanities Core H1CS 13 June 2020 Becoming Anti-Human: How Lovecraftian Horror Philosophically Deconstructs Otherness The most horrifying monster is change. Having the comfort and consistency of normality be thrust into the foreign landscape of difference can be petrifying. The dormant mind can lose its sense of self, security, and, worst of all, control. In the horror genre, this is no different. Monsters are frightening because of the difference they impose on us and our identity. Imagining a world ruled by a zombie apocalypse or a ravenous vampire feasting at night may seem unobtrusive, but when the rabid ghoul trespasses the border of detached fiction into the interior of one’s identity, the cliche skeleton seems almost an afterthought. Much more terrifying than the grotesqueness or typicality of these horror villains is how they can turn one’s sense of self and control inside out. It invites the elusive glance inward, asking the subject to wonder if their pillars of psychological safety—identity, family, belief system, home—are very safe at all. This fear of something different is compartmentalized by the psyche as something so alien, so invasive, that it must be something Other. This effect is explored by the stories of Howard Philips Lovecraft, a horror writer whose stories are so bizarre that the average reader is stripped of all their preconceptions about reality and even their sense of self. This special subgenre of horror was pioneered by Lovecraft and is famously called “Lovecraftian horror” but is well known today as cosmic horror: A mesh of horror and science fiction that “erodes presumptions about the nature of reality” (Cardin 273). -

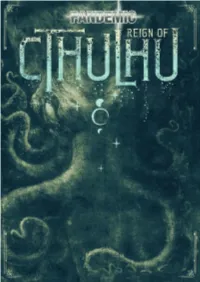

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

This Paper Examines the Role of Media Technologies in the Horror

Monstrous and Haunted Media: H. P. Lovecraft and Early Twentieth-Century Communications Technology James Kneale his paper examines the role of media technologies in the horror fic- tion of the American author H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937). Historical geographies of media must cover more than questions of the distri- Tbution and diffusion of media objects, or histories of media representations of space and place. Media forms are both durable and portable, extending and mediating social relations in time and space, and as such they allow us to explore histories of time-space experience. After exploring recent work on the closely intertwined histories of science and the occult in late nine- teenth-century America and Europe, the discussion moves on to consider the particular case of those contemporaneous media technologies which became “haunted” almost as soon as they were invented. In many ways these hauntings echo earlier responses to the printed word, something which has been overlooked by historians of recent media. Developing these ideas I then suggest that media can be monstrous because monstrosity is centrally bound up with representation. Horrific and fantastic fictions lend themselves to explorations of these ideas because their narratives revolve around attempts to witness impossible things and to prove their existence, tasks which involve not only the human senses but those technologies de- signed to extend and improve them: the media. The remainder of the paper is comprised of close readings of several of Lovecraft’s stories which sug- gest that mediation allowed Lovecraft to reveal monstrosity but also to hold it at a distance, to hide and to distort it. -

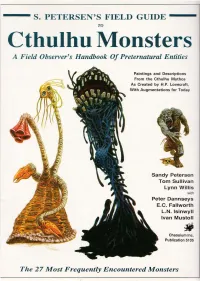

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Pandemic – Reign of Cthulhu Is a Cooperative Game

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

Cthulhu Through the Ages Is Copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc

AUTHORS Mike Mason, Pedro Ziviani, John French, and Chad Bowser EDITING Mike Mason and Dustin Wright CARTOGRAPHY Stephanie McAlea INVESTIGATOR SHEETS Dean Engelhardt LAYOUT Nicholas Nacario COVER ILLUSTRATION Paul Carrick INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Steven Gilberts, Sam Lamont, Florian Stitz, Paul Carrick, Goomi, Raymond Bayless, Nicholas Nacario. Some images were taken from Wikicommons and are in the public domain. THANKS TO Alan Bligh, John French, Matt Anderson, Penda Tomlin- son, and Dustin Wright. A special thanks to all of our 7th edition kickstarter backers who helped make this book possible. This supplement is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 Cthulhu Through the Ages is copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. The names of public personalities may be referred to, but any resemblance of a scenario character to persons liv- ing or dead is strictly coincidental. Except in this publication and associated advertising, all illustrations for CTHULHU THROUGH THE AGES remain the property of the artists, who otherwise reserve all rights. This adventure pack is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Item # 23146 ISBN10: 1568824386 ISBN13: 978-1568824383 Printed in USA Contents Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 5 Cthulhu Invictus ������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Herbert West — Reanimator

DARK ADVENTURE RADIO THEATRE: HERBERT WEST — REANIMATOR Written by Sean Branney and Andrew Leman Based on "Herbert West — Reanimator" by H. P. Lovecraft Read-along Script June 18, 2013 ©2013 by HPLHS Inc. All Rights Reserved. NOTICE: This script is provided as a convenience only to DART listeners to follow along with the recorded show. It is not licensed for professional or amateur performance of any kind. Inquiries regarding performance rights should be sent to [email protected] 1 INTRO 1 SFX: static, radio tuning, snippet of ‘30s song, more tuning, static dissolves to: Dark Adventure Radio THEME MUSIC. ANNOUNCER Tales of intrigue, adventure, and the mysterious occult that will stir your imagination and make your very blood run cold. MUSIC CRESCENDO. ANNOUNCER (CONT’D) This is Dark Adventure Radio Theatre, with your host Erskine Blackwell. Today’s episode: H.P. Lovecraft’s “Herbert West -- Reanimator!” THEME MUSIC DIMINISHES. The sound of MOANING, BUBBLING CHEMICALS, and FUNEREAL MUSIC underneath. ERSKINE BLACKWELL A brilliant medical student dreams of bringing life to the dying, and to the dead. How far will he go to achieve his dream? Will his genius unlock the secrets of life and death, or will boundless ambition twist his noble purpose into something monstrous? A few piano notes from the FORHAN’S TOOTHPASTE JINGLE. ERSKINE BLACKWELL (CONT’D) You know, folks, nothing says success quite like a bright radiant smile. And for truly gleaming teeth, there’s no better toothpaste than Forhan’s, now with new Radiol! It’s the very latest thing: a safe extract of radium, scientifically developed in the finest medical laboratories of Europe. -

Lovecraft Patrons

Lovecraft Patrons Subclasses Specific to Various Great Old Ones of the Cthulhu Mythos By Zach Hitzeroth DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission Sampleof Wizards of the Coast. file ©2020 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Note on Expanded Spell Lists Player's Handbook Only Spells Spells marked with an asterisk are from Xanathar's 4th Level: fabricate Guide to Everything. If your DM does not allow these spells, alternate spells from the Player's Handbook can be found at the end of each subclass. Abhoth Also known as the Source of Uncleanliness, Abhoth is an Outer God depicted as an ooze or slime from which monsters and unnamable horrors crawl from. Followers of Abhoth tend to spread disease and carry oozes around with them to symbolize their patron. Expanded Spell List Abhoth lets you choose from an expanded list of spells when you learn a warlock spell. -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime.