SHETLAND in SAGA-TIME: Rereading the Orkneyinga Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 St Magnus Earl of Orkney

UHI Research Database pdf download summary Storyways Gibbon, Sarah Jane; Moore, James Published in: Open Archaeology Publication date: 2019 Publisher rights: © 2019 Sarah Jane Gibbon et al., published by De Gruyter. The re-use license for this item is: CC BY The Document Version you have downloaded here is: Peer reviewed version The final published version is available direct from the publisher website at: 10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Link to author version on UHI Research Database Citation for published version (APA): Gibbon, S. J., & Moore, J. (2019). Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape. Open Archaeology, 5(1), 235-262. https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights: 1) Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the UHI Research Database for the purpose of private study or research. 2) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 3) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Open Archaeology 2019; 5: 235–262 Original Study Sarah Jane Gibbon*, James Moore Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Received February 28, 2019; accepted May 17, 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a new methodological approach and theorising framework which visualises intangible landscapes. -

THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

THE VIKINGS IN ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell Introduction In recent years, it has been suggested that the first permanent Scandinavian presence in Orkney was not the result of forcible land-taking by Vikings, but came about instead through gradual penetration - a period which has been described as one of'informal' settlement (Morris 1985: 213; 1998: 83). Such would have involved a phase of co-existence, or even integration, between the native Picts and the earliest Norse settlers. This initial period, it is supposed, was then followed by 'a second, formal, settlement associated with the estab lishment of an earldom' (Morris 1998: 83 ), in the late 9'h century. The archaeological evidence advanced in support of the first 'period of overlap' is, however, open to alternative interpretation and, indeed, Alfred Smyth has com mented ( 1984: 145), in relation to the annalistic records of the earliest Viking attacks on Ireland, that these 'strongly suggest that the Norwegians did not gradually infiltrate the Northern Isles as farmers and fisherman and then sud denly tum nasty against their neighbours'. Others have supposed that the first phase of Norse settlement in Orkney would have involved, in the words of Buteux (1997: 263): 'ness-taking' (the fortifying of a headland by means of a cross-dyke) and the occupation of small off-shore islands. Crawford ( 1987: 46) argues that headland dykes on Orkney can be interpreted as indicating ness-taking. However many are equally likely to be prehistoric land boundaries, and no bases on either headlands or small islands have yet been positively identified. Buteux continues his discussion by observing, most pertinently, that: While this can not be taken as suggesting that such sites do not remain to be uncovered, the striking fact is that almost all identified Viking-period settlements in the Northern Isles are found overlying or immediately adjacent to sites which were occupied in the preceding Pictish period and which, furthermore, had frequently been settlements of some size and importance. -

Brough of Birsay Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC278 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90034) Taken into State care: 1933 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGH OF BIRSAY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH BROUGH OF BIRSAY BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises an area of Pictish to medieval settlement and ecclesiastical remains, situated on part of a small tidal island off the NW corner of Mainland Orkney. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Scripta Islandica 66/2015

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 66/2015 REDIGERAD AV LASSE MÅRTENSSON OCH VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) Henrik Williams (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SWEDEN Publicerad med stöd från Vetenskapsrådet. © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2015 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Ord och sats Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-260648 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-260648 Innehåll LISE GJEDSSØ BERTELSEN, Sigurd Fafnersbane sagnet som fortalt på Ramsundsristningen . 5 ANNE-SOFIE GRÄSLUND, Kvinnorepresentationen på de sen vikinga- tida runstenarna med utgångspunkt i Sigurdsristningarna ....... 33 TERRY GUNNELL, Pantheon? What Pantheon? Concepts of a Family of Gods in Pre-Christian Scandinavian Religions ............. 55 TOMMY KUUSELA, ”Den som rider på Freyfaxi ska dö”. Freyfaxis död och rituell nedstörtning av hästar för stup ................ 77 LARS LÖNNROTH, Sigurður Nordals brev till Nanna .............. 101 JAN ALEXANDER VAN NAHL, The Skilled Narrator. Myth and Scholar- ship in the Prose Edda .................................. 123 WILLIAM SAYERS, Generational Models for the Friendship of Egill and Arinbjǫrn (Egils saga Skallagrímssonar) ................ 143 OLOF SUNDQVIST, The Pre-Christian Cult of Dead Royalty in Old Norse Sources: Medieval Speculations or Ancient Traditions? ... 177 Recensioner LARS LÖNNROTH, rec. av Minni and Muninn: Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture, red. Pernille Herrmann, Stephen A. Mitchell & Agnes S. Arnórsdóttir . 213 OLOF SUNDQVIST, rec. av Mikael Males: Mytologi i skaldedikt, skaldedikt i prosa. En synkron analys av mytologiska referenser i medeltida norröna handskrifter .......................... 219 PER-AXEL WIKTORSSON, rec. av The Power of the Book. Medial Approaches to Medieval Nordic Legal Manuscripts, red. Lena Rohrbach ............................................ 225 KIRSTEN WOLF, rev. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

NOTES on the EAELDOM of CAITHNESS. by W. F. SKENE, LL.D., F.S.A

NOTES ON THE EAELDOM OF CAITHNESS. By W. F. SKENE, LL.D., F.S.A. SOOT. The earldom of Caithness was possessed for many generations by the Norwegian Earls of Orkney. They held the Islands of Orkney undur e Kinth f Norwago y accordin o Norwegiagt n custom whicy b , e titlhth e of Jarl or Earl was a personal title. They held the earldom of Caith- ness unde Kine f th rScotland o g s tenuraccordancn it i s d ewa an , e with lawe th Scotlandf o s . fine W d fro Orkneyinge mth a Saga that during this perio Orknee dth y islands were frequently divided into two portions, and each half held by different members of the Norwegian family, each bearing the title of earl. We likewise find that the earldom of Caithness was at such times also frequently divided, and each half held by different Earls of Orkney, though whether both bore the title of Earl of Caithness does not appear. It is unnecessary for our purpose to go further back than the rale of Thorfinn, Ear f Orkneyo l dieo dwh , about A.U. 1056 undoubtedld an , y held the whole of the Orkneys and the entire earldom of Caithness for lona g period. He had two sons, Paul and Erlend, who after his death ruled jointly without dividing the earldoms theid an , r descendant termee b y e dth sma line of Paul and the line of Erlend. 572 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, MARCH 11, 1878. After their deat e islandth h s were divided between f Hakono n so , Paul, and Magnus, son of Erlend, each bearing the title of earl. -

Heimskringla III.Pdf

SNORRI STURLUSON HEIMSKRINGLA VOLUME III The printing of this book is made possible by a gift to the University of Cambridge in memory of Dorothea Coke, Skjæret, 1951 Snorri SturluSon HE iMSKrinGlA V oluME iii MAG nÚS ÓlÁFSSon to MAGnÚS ErlinGSSon translated by AliSon FinlAY and AntHonY FAulKES ViKinG SoCiEtY For NORTHErn rESEArCH uniVErSitY CollEGE lonDon 2015 © VIKING SOCIETY 2015 ISBN: 978-0-903521-93-2 The cover illustration is of a scene from the Battle of Stamford Bridge in the Life of St Edward the Confessor in Cambridge University Library MS Ee.3.59 fol. 32v. Haraldr Sigurðarson is the central figure in a red tunic wielding a large battle-axe. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ vii Sources ............................................................................................. xi This Translation ............................................................................. xiv BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES ............................................ xvi HEIMSKRINGLA III ............................................................................ 1 Magnúss saga ins góða ..................................................................... 3 Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar ............................................................ 41 Óláfs saga kyrra ............................................................................ 123 Magnúss saga berfœtts .................................................................. 127 -

Orcadians (And Some Shetlanders) Who Worked West of the Rockies in the Fur Trade up to 1858 (Unedited Biographies in Progress)

Orcadians (and some Shetlanders) who worked west of the Rockies in the fur trade up to 1858 (unedited biographies in progress) As compiled by: Bruce M. Watson 208-1948 Beach Avenue Vancouver, B. C. Canada, V6G 1Z2 As of: March, 1998 Information to be shared with Family History Society of Orkney. Corrections, additions, etc., to be returned to Bruce M. Watson. A complete set of biographies to remain in Orkney with Society. George Aitken [variation: Aiken ] (c.1815-?) [sett-Willamette] HBC employee, British: Orcadian Scot, b. c. August 20, 1815 in "Greenay", Birsay, Orkney, North Britain [U.K.] to Alexander (?-?) and Margaret [Johnston] Aiken (?-?), d. (date and place not traced), associated with: Fort Vancouver general charges (l84l-42) blacksmith Fort Stikine (l842-43) blacksmith steamer Beaver (l843-44) blacksmith Fort Vancouver (l844-45) blacksmith Fort Vancouver Depot (l845-49) blacksmith Columbia (l849-50) Columbia (l850-52) freeman Twenty one year old Orcadian blacksmith, George Aiken, signed on with the Hudson's Bay Company February 27, l836 and sailed to York Factory where he spent outfits 1837-40; he then moved to and worked at Norway House in 1840-41 before being assigned to the Columbia District in 1841. Aiken worked quietly and competently in the Columbia district mainly at coastal forts and on the steamer Beaver as a blacksmith until March 1, 1849 at which point he went to California, most certainly to participate in the Gold Rush. He appears to have returned to settle in the Willamette Valley and had an association with the HBC until 1852. Aiken's family life or subsequent activities have not been traced. -

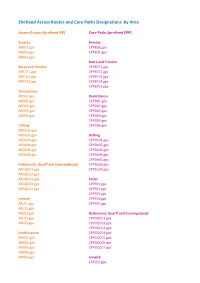

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Scotland: Bruce 286

Scotland: Bruce 286 Scotland: Bruce Robert the Bruce “Robert I (1274 – 1329) the Bruce holds an honored place in Scottish history as the king (1306 – 1329) who resisted the English and freed Scotland from their rule. He hailed from the Bruce family, one of several who vied for the Scottish throne in the 1200s. His grandfather, also named Robert the Bruce, had been an unsuccessful claimant to the Scottish throne in 1290. Robert I Bruce became earl of Carrick in 1292 at the age of 18, later becoming lord of Annandale and of the Bruce territories in England when his father died in 1304. “In 1296, Robert pledged his loyalty to King Edward I of England, but the following year he joined the struggle for national independence. He fought at his father’s side when the latter tried to depose the Scottish king, John Baliol. Baliol’s fall opened the way for fierce political infighting. In 1306, Robert quarreled with and eventually murdered the Scottish patriot John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, in their struggle for leadership. Robert claimed the throne and traveled to Scone where he was crowned king on March 27, 1306, in open defiance of King Edward. “A few months later the English defeated Robert’s forces at Methven. Robert fled to the west, taking refuge on the island of Rathlin off the coast of Ireland. Edward then confiscated Bruce property, punished Robert’s followers, and executed his three brothers. A legend has Robert learning courage and perseverance from a determined spider he watched during his exile. “Robert returned to Scotland in 1307 and won a victory at Loudon Hill.